Alexander the Great: Western Civilization Research Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

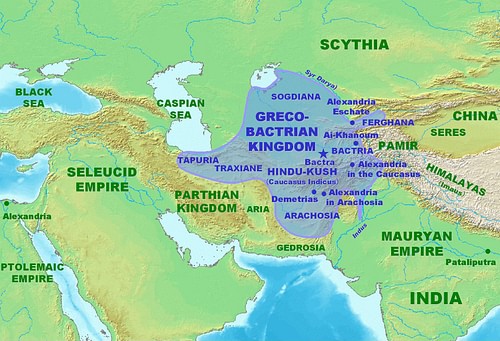

Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) was an ancient Greek ruler and the king of the state of Macedon (Cummings, 2004, p.54). He was a student of Aristotle, and established a vast empire by the time he was 30 years of age. The empire stretched from the Ionian Sea to the Himalayas, and was a sign of his greatness.

Alexander won every battle and expanded his empire by conquering smaller empires whose armies were not as powerful as his. He assumed the throne after the assassination of his father, Philip II of Macedon in 336 BC (Cummings, 2004, p.54).

A well-established kingdom and a strong army were some of the reasons why he became so great. In his capacity as an army commander, politician, king, explorer and scholar, Alexander used several strategies to expand his empire that encompassed people from different ethnic backgrounds. He had immense influence on western civilization mainly because he introduced the Greek language, science and culture to the new empires that he conquered in an effort to expand his empire (Cummings, 2004, p.58).

Alexander used his powerful army to conquer the world during his time. Whenever he conquered new empires, he introduced the Greek language, science knowledge and other aspects of Greek civilization (Noble, 2008, p.95). As an explorer, Alexander discovered that the world extended beyond the Indus River.

He made this discovery with the aid of his geographers who helped him to explore new lands. In addition, he introduced certain aspects of different cultures that he felt were useful in conquering more empires and continuing his reign.

One of the main influences of Alexander on western civilization was his policies on commerce. He established roads that facilitated commerce with the western world after conquering Persia (Noble, 2008, p.96).

These roads were in existence before but inaccessible to the western world because they were under the control of the Persians. This monopoly diminished the chances of the western world of trading and conducting commerce with India, China, Bactria and many other countries that were famous for their trade acumen at that time.

The opening of these roads established trade between the west and these countries. This led to the introduction of precious metals and stones, jewelry and jade to the west (Noble, 2008, p.97). For example, Silk Road is one of the many roads that Alexander the Great opened to the western world. These roads exposed the west to other parts of the world.

Alexander combined his capacities as king and scholar to establish and develop his empires. In order to control the populations of the empires that he conquered, he adopted some of their traditions. This led to the establishment of an ideological king, a concept that ensured that the kingdom remained strong.

However, it split into three empires after his demise due to bad leadership (Noble, 2008, p.99). Alexander had a significant influence because of his brilliant thinking. He envisioned a massive empire that constituted many states under his control. In today’s context, the empire that Alexander built can be compared to the United States of America. His extraordinary ideas enabled him to conquer other empires and encompass them under his rule.

The spread of the Greek language to other parts of the world was due to the introduction of the Macedonian culture to the Persian Empire. The introduction of the Greek language led to its adoption in governing and ruling the empire. This encompassed many people under a common language and introduced the cultures, thoughts, ideas and beliefs of other empires (Spielvogel, 2011, p.96).

For example, the translation of the Old Testament in Greek introduced Christianity to the western world. The Old Testament was originally in Hebrew and was limited to people who understood that language. The translation was initially intended for Hebrews who had lived in other places for long periods, and therefore, unable to read in the Hebrew language. However, this brought the Jewish theology to other parts of the world.

This theology introduced the concept of monotheism that formed the basis of Christianity for the western world (Spielvogel, 2011, p.92). Alexander the Great influenced the establishment of religion in the west through popularizing the Greek language. The Greek language made the introduction of the New Testament possible and was phenomenal in promoting Christianity (Spielvogel, 2011, p.93).

The most influential change on western civilization was the concept of monotheism (Spielvogel, 2011, p.96). This was the basis for the founding of Christianity. It all started with the dispersion of Jews into different regions due to war and violence. Gradually, these immigrants led to the adoption of Greek as a common language. As a result, many Jews spoke Greek and started translating their literature into the Greek language. The most notable was the translation of the bible. In addition, the Hellenist world had monumental influence on the spread of Christianity to the west. For example, Paul was a Jew from Tarsus who incorporated some Hellenistic elements in his teaching. This made the teachings pleasant to many people who responded by embracing Christianity (Spielvogel, 2011, p.97).

Alexander introduced Hellenism and the Greek culture that were pivotal in the founding of the renaissance and the Enlightenment movements (Staufenberg, 2011, p.52). After his death, people became more knowledgeable than they were before his death. They became aware of the fact that the world was much larger than it was thought to be during Alexander’s reign.

Therefore, they explored more lands and travelled to many places. This marked the commencement of the modern world. History teaches that the modern world began with the renaissance because the Hellenistic period was partially responsible for civilization. This is because most of the advancements during the era of Alexander became obsolete as the empire crumbled after his death (Staufenberg, 2011, p.53).

During the middle ages, people wallowed in ignorance and retrogressed from the progress that was initiated by Alexander’s rule. Progress began again when the Turks took over Byzantium and when Christians began to migrate to Rome (Staufenberg, 2011, p.58). They introduced the culture and the civilization that was promoted by Alexander the Great.

Another aspect of Alexander’s rule that had a significant impact on western civilization was his economic policies. Alexander’s reign was highly influential to the economy of the Mediterranean basin. This resulted in enormous social and economic changes that had a positive effect on the west (Staufenberg, 2011, p.62).

These social and economic changes influenced other areas such as medicine and philosophy. For example, Alexandria was the center of medical research. Researchers learned how to carry out surgical operations and diagnose various diseases (Staufenberg, 2011, p.65). These medical advancements reached the west and formed a basis for their medical fields that are among the most advanced in the world today.

Under Alexander’s reign, there was immense spread of the Hellenistic civilization that made Greek the language that was used to conduct business. Under a common language, trade prospered and Alexandria became the center of trade. It was famous for the manufacture and importation of products.

The products that were produced by the Egyptians included silk, wine, cosmetics, cloth, salt, glass, beer and paper (Staufenberg, 2011, p.72). In the western parts of Asia, common products included asphalt, carpets, petroleum, drugs and woolens. The effect of trade on the involved regions was immense. During the years that followed the death of Alexander, the region of Judea became inhabited by Greek merchants and government officials.

Gradually, these new inhabitants began to “Hellenize” the original inhabitants of the region. In addition, there was dispersion and migration as violence erupted in different parts of the empire. As they moved to new places, they carried their civilization and brought about various changes in the culture of the inhabitants.

As a scholar, Alexander had strong interests in science, mathematics, geometry, arts and literature. It is difficult to determine in which of these fields Alexander had the greatest influence on the western civilization. The artwork created by the great artists of the Hellenistic era is similar to that of the renaissance artists that is common today (Spielvogel, 2011, p.103).

This implies that the Hellenistic period influenced the work of artists that lived during the renaissance period. For example, today’s cities are designed using a grid plan that was developed by Hippodamus of Miletus (Spielvogel, 2011, p.106).

In addition, the geometry developed by Archimedes is used in the building and construction industry. Literature from the era is still available today, and the fields of history and chronology were established during the same era (Spielvogel, 2011, p.108). All these aspects of the Hellenistic period were vital in developing the western civilization. The development of these aspects was made possible by the rule of Alexander the Great, and the western world owes its civilization to him.

Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) was an ancient Greek ruler in the state of Macedon. He assumed the throne after the assassination of his father, Philip II of Macedon in 336 BC. A strong army and a well-established kingdom were some of the reasons why he became so influential.

In his many capacities as an army commander, politician, king, explorer and a scholar, Alexander used several strategies to expand his empire that included people from different ethnic backgrounds. The most influential change on western civilization was the concept of monotheism. This was the basis for the founding of Christianity.

He had a significant influence on western civilization mainly because he introduced the Greek language and science to the new empires that he conquered as he tried to expand his empire. He influenced western civilization through art, literature, science and geometry.

These aspects were critical in developing the western civilization. He had immense influence on western civilization mainly because he introduced the Greek language, science and culture to the new empires that he conquered in an effort to expand his empire. Alexander the Great had significant influence on western civilization, and the western world owes its civilization to him.

Cummings, L. (2004). Alexander the Great . New York: Grove Press.

Noble, T. 92008). Western Civilization: Beyond Boundaries . Stamford, Connecticut: Cengage Learning.

Spielvogel, J. (2011). Western Civilization . Stamford, Connecticut: Cengage Learning.

Staufenberg, G. (2011). Building Blocks of Western Civilization . New York: Xlibris Corporation.

- The Genius of Alexander the Great

- Alexander the Great: A Pioneer of Western Civilization

- Alexander the Great's Reign

- Witchcraft in Europe, 1450 – 1750

- History of French Revolution

- 1700s as a Period of Diverse Changes in Europe

- Major social groups in France prior to the French revolution

- What Caused the French Revolution?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 2). Alexander the Great: Western Civilization. https://ivypanda.com/essays/alexander-the-great-and-the-western-civilization/

"Alexander the Great: Western Civilization." IvyPanda , 2 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/alexander-the-great-and-the-western-civilization/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Alexander the Great: Western Civilization'. 2 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Alexander the Great: Western Civilization." July 2, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/alexander-the-great-and-the-western-civilization/.

1. IvyPanda . "Alexander the Great: Western Civilization." July 2, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/alexander-the-great-and-the-western-civilization/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Alexander the Great: Western Civilization." July 2, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/alexander-the-great-and-the-western-civilization/.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Alexander the Great

Introduction.

- Alexander the Great Online

- Collections of Papers

- Bibliographies and Dictionaries

- Lost Alexander Histories

- Individual Lost Historians

- Questionable Contemporary Documents

- Babylonian Accounts

- Extant Ancient Accounts of Alexander

- Epigraphic Evidence

- Numismatic Evidence

- Artistic Evidence

- Archaeological Evidence

- Topography and Alexander’s March

- Macedonian Background

- Alexander’s Youth and Philip II

- Alexander’s Relationships with the Greeks

- Alexander in Europe, 338–336, the Destruction of Thebes, 335, and Agis III’s Revolt, 331

- The Gordian Knot

- The Units of Alexander’s Army

- The Major Battles

- The Naval Campaign and the Siege of Tyre

- Economy and Finance

- Foundation of Cities

- Alexander’s Court

- Non-military Aspects of Alexander’s Campaign

- Alexander and the Macedonian Elite and Troops

- The Fire at Persepolis

- Alexander’s Religion and Divinity

- Alexander in Central Asia and India, 330/329–326/325

- The Gedrosian March and Nearchus’s Voyage, 325

- The Mass Marriages in Susa

- The Opis Mutiny

- The Harpalus Affair and the Exiles Decree

- The Death of Hephaestion

- The Planned Arabian Campaign and the Death of Alexander

- Alexander’s Posthumous Image

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Greek History: Hellenistic

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Ancient Greek Polychromy

- The Parthian Empire

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Alexander the Great by Joseph Roisman LAST REVIEWED: 25 February 2016 LAST MODIFIED: 25 February 2016 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195389661-0114

It has been said about Alexander the Great (b. 356–d. 323 BCE ) that his name marked the end of an old world epoch and the beginning of a new one. Alexander’s empire that stretched from the Danube to India indeed ushered in the Hellenistic age, when Greek culture expanded and merged with Asian and African cultures in the territories he conquered and even beyond. While Alexander’s military record has gained him lasting fame, views of his character, his treatment of compatriots and subjects, and even the merits of his accomplishments have varied greatly since Antiquity. The continuing interest in Alexander has produced numerous works of scholarship and fiction that this article does not presume to cover. Instead, preference is given to recent scholarly works, in which older studies are cited, as well as to works deemed influential, innovating, or useful, although the decision about their significance is bound to be controversial. The article is arranged by topics, with less consideration to the chronology of the campaign. It also does not include works on ancient Macedonia and the Achaemenid Empire. All dates in this entry are BCE unless noted otherwise. Lists of common abbreviations of authors and works used by scholars can be found in the Oxford Classical Dictionary or the bibliographical journal L’Année Philologique .

General Overviews and Monographs

Johann Gustav Droysen’s idealized portrait of Alexander in his History of Alexander the Great , first published in 1833 ( Geschichte Alexanders des Großen [Hamburg: F. Perthes]), has exerted influence on scholars and laypersons up until today. Not everyone, however, felt similar admiration for the Macedonian king, and especially not Karl Julius Beloch. This German historian depicted Alexander in his “Greek history” ( Griechische Geschichte , 2d new ed. 4 vols. [Strassburg: Trübner, 1912–1917]) as a tyrant who allowed the Orient to conquer him in a way that paved the road to Byzantium. Droysen and Beloch represent the two polar views of Alexander, with the former picking sources that favored the king and the latter taking a much harsher and more critical approach. Indeed, the diversity of opinions of Alexander goes back to the sources about him that informed their modern interpreters. Individual Alexander historians can be placed anywhere on the continuum between Droysen and Beloch. Often, and as was the case with Droysen and Beloch, the experience and historical circumstances of historians affected to some degree their interpretations of Alexander. Of the citations listed in this section, Tarn 1948 , Hammond 1989 , Lane Fox 1973 , and Martin and Blackwell 2012 hold a high opinion of the king, while Bosworth 1988 , Schachermeyer 1973 , and to a lesser extent Green 1992 are much more critical. The opinions of Cartledge 2004 , Briant 2010 , Anson 2013 , and Worthington 2014 are mixed. Since Bosworth published his history of Alexander in 1988, no other monograph has surpassed it. See also Worthington 2004 , cited under Alexander’s Youth and Philip II .

Anson, Edward M. 2013. Alexander the Great: Themes and issues . London: Bloomsbury Academic.

As opposed to a biography of the king, the book discusses the main issues of his career and its Greco-Macedonian background. Succinct summaries of scholarly opinions and the author’s suggested solutions to problems related to the history of Alexander makes it a useful work.

Bosworth, Albert Brian. 1988. Conquest and empire: The reign of Alexander the Great . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Written by the leading expert on the topic, this book is arguably the best account of Alexander’s history to date. In addition to describing the Asian expedition, the book examines key aspects of Alexander’s reign and campaign.

Briant, Pierre. 2010. Alexander the Great and his empire: A short introduction . Translated by Amelie Kuhrt. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

The book is an updated and revised version of the author’s 2002 Alexandre le Grand (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France). It deals with the campaign thematically and with subjects such as Alexander’s motives, administration, the Persian response, numismatic and Near Eastern evidence, and his death. Briant’s Alexander is essentially a rational, pragmatic king.

Cartledge, Paul. 2004. Alexander the Great: The hunt for a new past . New York: Vintage.

A well-written and user-friendly account, which, although aiming at the nonspecialist, is well suited as an introduction to the subject.

Green, Peter. 1992. Alexander of Macedon, 356–323 B.C.: A historical biography . Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

When first published in 1974 the book served as a welcomed antidote to the glorifying portrait of the king in Tarn 1948 . It is still valuable for its expansive panorama, insights, and balanced view of Alexander.

Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière. 1989. Alexander the Great: King, commander and statesman . 2d ed. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes.

Written by a leading expert on ancient Macedonia, the book examines Alexander’s leadership qualities and especially his excellence as a general. The view is highly favorable, and the author refuses at times to acknowledge the value of sources other than Arrian’s Anabasis .

Lane Fox, Robin. 1973. Alexander the Great . London: Allen Lane.

This is one of the more popular books on Alexander and has been translated into a number of languages. The style is engaging, and the king resembles a Homeric hero more in line with Droysen than with Beloch or Bosworth. The notes are inconveniently grouped at the end of the book but are exhaustive, especially about the ancient evidence.

Martin, Thomas R., and Christopher Blackwell. 2012. Alexander the Great: The story of an ancient life . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781139049498

An accessible book that offers a highly positive, at times even admiring, portrait of the king in contrast to the critical approach more common in current scholarship.

Schachermeyer, Fritz. 1973. Alexander der Grosse: Das Problem seiner Persönlichkeit und seines Wirkens . Sitzungsberichte der philosophisch-historischen Klasse 285. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

This hefty book is a reprint with occasional updates and modifications of the author’s 1949 monograph Alexander der Grosse: Ingenium und Macht (Graz, Austria: A. Pustet). There is much to learn from the erudite analysis, but the irritating rhetorical style, the excessive infusing of psychology, and the impact of the Nazi experience on the interpretation detract from the book’s value. The author’s paying tribute to Nazi ideology in previous publications should not be ignored.

Tarn, William Woodthorpe. 1948. Alexander the Great . 2 vols. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Much inspired by Droysen’s Geschichte Alexanders des Großen , Tarn’s Alexander is a flawless leader who dreamt of the unity of mankind under his benevolent rule. The thesis was demolished especially by Ernest Badian’s works (see Badian 2012 and Badian 1976 , cited under Collections of Papers , and Badian 1958 , cited under Alexander’s Aims and Plans ). Yet a number of individual investigations in the second volume are still useful.

Worthington, Ian. 2014. By the spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the rise and fall of the Macedonian Empire . Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

The book describes the reigns of Philip II and Alexander and compares and contrasts the challenges they faced as well as their roles as empire- and nation- builders, with Philip getting the higher marks.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Classics »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academy, The

- Acropolis of Athens, The

- Aeschylus’s Oresteia

- Aesthetics, Greek and Roman

- Africa, Roman

- Agriculture in the Classical World

- Agriculture, Roman

- Alexander of Aphrodisias

- Alexander the Great

- Ammianus Marcellinus

- Anatolian, Greek and

- Ancient Classical Scholarship

- Ancient Greek and Latin Grammarians

- Ancient Greek Terracotta Sculpture

- Ancient Mediterranean Baths and Bathing

- Ancient Skepticism

- Ancient Thebes

- Antisthenes

- Antonines, The

- Apollodorus

- Apollonius of Rhodes

- Appendix Vergiliana

- Apuleius's Platonism

- Ara Pacis Augustae

- Arabic “Theology of Aristotle”, The

- Archaeology, Greek

- Archaeology, Roman

- Archaic Latin

- Architecture, Etruscan

- Architecture, Greek

- Architecture, Roman

- Arena Spectacles

- Aristophanes

- Aristophanes’ Clouds

- Aristophanes’ Lysistrata

- Aristotle, Ancient Commentators on

- Aristotle's Categories

- Aristotle's Ethics

- Aristotle's Metaphysics

- Aristotle's Philosophy of Mind

- Aristotle’s Physics

- Aristotle's Politics

- Art and Archaeology, Research Resources for Classical

- Art, Etruscan

- Art, Late Antique

- Athenaeus of Naucratis

- Athenian Agora

- Athenian Economy

- Attic Middle Comic Fragments

- Aulularia, Plautus’s

- Aulus Gellius

- Bacchylides

- Banking in the Roman World

- Bilingualism and Multilingualism in the Roman World

- Biography, Greek and Latin

- Birds, Aristophanes'

- Britain, Roman

- Bronze Age Aegean, Death and Burial in the

- Caecilius Statius

- Caere/Cerveteri

- Callimachus of Cyrene

- Carthage, Punic

- Casina, Plautus’s

- Cato the Censor

- Cato the Younger

- Christianity, Early

- Cicero’s Philosophical Works

- Cicero's Pro Archia

- Cicero's Rhetorical Works

- Cities in the Roman World

- Classical Architecture in Europe and North America since 1...

- Classical Architecture in Renaissance and Early Modern Eur...

- Classical Art History, History of Scholarship of

- Classics and Cinema

- Classics and Dance

- Classics and Opera

- Classics and Shakespeare

- Classics and the Victorians

- Claudian (Claudius Claudianus)

- Cleisthenes

- Codicology/Paleography, Greek

- Collegia, Roman

- Colonization in the Roman Empire

- Colonization in the Roman Republic

- Constantine

- Corpus Tibullianum Book Three

- Countryside, Roman

- Crete, Ancient

- Critias of Athens

- Death and Burial in the Roman Age

- Declamation

- Demography, Ancient

- Demosthenes

- Dio, Cassius

- Diodorus Siculus

- Diogenes Laertius

- Doxography, Ancient

- Drama, Latin

- Economy, Roman

- Egypt, Hellenistic and Roman

- Epicurean Ethics

- Epicureanism

- Epigram, Greek Inscribed

- Epigrams, Greek Poetry

- Epigraphy, Greek

- Epigraphy, Latin

- Eratosthenes of Cyrene

- Etymology, Greek Lexicon and

- Euripides' Alcestis

- Euripides’ Bacchae

- Euripides’ Electra

- Euripides' Orestes

- Euripides’ Trojan Women

- Fabius Pictor

- Family, Roman

- Federal States, Greek

- Fishing and Aquaculture, Roman

- Flavian Literature

- Fragments, Greek Old Comic

- Frontiers of the Roman Empire

- Gardens, Greek and Roman

- Gaul, Roman

- Gracchi Brothers, The

- Greek and Roman Logic

- Greek Colonization

- Greek Domestic Architecture c. 800 bce to c. 100 bce

- Greek Epic, The Language of the

- Greek New Comic Fragments

- Greek Originals and Roman Copies

- Greek Prehistory Through the Bronze Age

- Greek Vase Painting

- Hellenistic Tragedy

- Herculaneum (Modern Ercolano)

- Herculaneum Papyri

- Heritage Management

- Historia Augusta

- Historiography, Greek

- Historiography, Latin

- History, Greek: Archaic to Classical Age

- History, Greek: Hellenistic

- History of Modern Classical Scholarship (Since 1750), The

- History, Roman: Early to the Republic

- History, Roman: Imperial, 31 BCE–284 CE

- History, Roman: Late Antiquity

- Homeric Hymns

- Homo novus/New man

- Horace's Epistles and Ars Poetica

- Horace’s Epodes

- Horace’s Odes

- Horace's Satires

- Imperialism, Roman

- Indo-European, Greek and

- Indo-European, Latin and

- Intertextuality in Latin Poetry

- Jews and Judaism

- Knossos, Prehistoric

- Land-Surveyors

- Language, Ancient Greek

- Languages, Italic

- Latin, Medieval

- Latin Paleography, Editing, and the Transmission of Classi...

- Latin Poetry, Epigrams and Satire in

- Lexicography, Greek

- Lexicography, Latin

- Linguistics, Indo-European

- Literary Criticism, Ancient

- Literary Languages of Greek, The

- Literary Letters, Greek

- Literary Letters, Roman

- Literature, Hellenistic

- Literature, Neo-Latin

- Looting and the Antiquities Market

- Magic in the Ancient Greco-Roman World

- Marcus Aurelius's Meditations

- Marcus Cornelius Fronto

- Marcus Manilius

- Maritime Archaeology of the Ancient Mediterranean

- Marius and Sulla

- Medea, Seneca's

- Menander of Athens

- Metaphysics, Greek and Roman

- Metrics, Greek

- Middle Platonism

- Military, Greek

- Military, Roman

- Miltiades of Cimon

- Minor Socratics

- Mosaics, Greek and Roman

- Mythography

- Narratology and the Classics

- Neoplatonism

- Neoteric Poets, The

- Nepos, Cornelius

- Nonius Marcellus

- Novel, Roman

- Novel, The Greek

- Numismatics, Greek and Roman

- Optimates/Populares

- Orpheus and Orphism

- Ovid’s Exile Poetry

- Ovid’s Love Poetry

- Ovid's Metamorphoses

- Painting, Greek

- Panaetius of Rhodes

- Panathenaic Festival, the

- Papyrology: Literary and Documentary

- Performance Culture, Greek

- Perikles (Pericles)

- Philo of Alexandria

- Philodemus of Gadara

- Philosophy, Dialectic in Ancient Greek and Roman

- Philosophy, Greek

- Philosophy of Language, Ancient

- Philosophy, Presocratic

- Philosophy, Roman

- Philostratus, Lucius Flavius

- Plato’s Apology of Socrates

- Plato’s Crito

- Plato's Laws

- Plato’s Metaphysics

- Plato’s Phaedo

- Plato’s Philebus

- Plato’s Sophist

- Plato's Symposium

- Plato’s Theaetetus

- Plato's Timaeus

- Plautus’s Amphitruo

- Plautus’s Curculio

- Plautus’s Miles Gloriosus

- Pliny the Elder

- Pliny the Younger

- Plutarch's Moralia

- Poetic Meter, Latin

- Poetry, Greek: Elegiac and Lyric

- Poetry, Greek: Iambos

- Poetry, Greek: Pre-Hellenistic

- Poetry, Latin: From the Beginnings through the End of the ...

- Poetry, Latin: Imperial

- Political Philosophy, Greek and Roman

- Posidippus of Pella

- Poverty in the Roman World

- Prometheus, Aeschylus'

- Prosopography

- Pyrrho of Elis

- Pythagoreanism

- Religion, Greek

- Religion, Roman

- Rhetoric, Greek

- Rhetoric, Latin

- Roman Agricultural Writers, The

- Roman Consulship, The

- Roman Italy, 4th Century bce to 3rd Century ce

- Roman Kingship

- Roman Patronage

- Roman Roads and Transport

- Sardis, Ancient

- Science, Greek and Roman

- Sculpture, Etruscan

- Sculpture, Greek

- Sculpture, Roman

- Seneca the Elder

- Seneca the Younger's Philosophical Works

- Seneca’s Oedipus

- Seneca's Phaedra

- Seneca's Tragedies

- Severans, The

- Silius Italicus

- Slavery, Greek

- Slavery, Roman

- Sophocles’ Ajax

- Sophocles’ Antigone

- Sophocles’ Electra

- Sophocles’ Fragments

- Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus

- Sophocles’ Oedipus the King

- Sophocles’ Philoctetes

- Sophocles’ Trachiniae

- Spain, Roman

- Stesichorus of Himera

- Symposion, Greek

- Technology, Greek and Roman

- Terence’s Adelphoe

- Terence’s Eunuchus

- The Sophists

- The Tabula Peutingeriana (Peutinger Map)

- Theater Production, Greek

- Theocritus of Syracuse

- Theoderic the Great and Ostrogothic Italy

- Theophrastus of Eresus

- Topography of Athens

- Topography of Rome

- Tragic Chorus, The

- Translation and Classical Reception

- Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature

- Valerius Flaccus

- Valerius Maximus

- Varro, Marcus Terentius

- Velleius Paterculus

- Wall Painting, Etruscan

- Zeno of Elea

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Beginnings of the Persian expedition

Asia minor and the battle of issus, conquest of the mediterranean coast and egypt, campaign eastward to central asia, invasion of india, consolidation of the empire.

Why is Alexander the Great famous?

What was alexander the great’s childhood like, how did alexander the great die, what was alexander the great like.

- What is imperialism in history?

Alexander the Great

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Constitutional Rights Foundation - The Legacy of Alexander the Great

- History World - History of Alexander The Great

- Chemistry LibreTexts - The Legacy of Alexander the Great

- Live Science - Alexander the Great: Facts, biography and accomplishments

- JewishEncyclopedia.com - Alexander, King of Greece

- JewishEncyclopedia.com - Alexander The Great

- Social Studies for Kids - Biography of Alexander the Great

- Khan Academy - Alexander the Great

- Livius - Biography of Alexander the Great

- PBS LearningMedia - The Rise of Alexander the Great

- World History Encyclopedia - Biography of Alexander the Great

- Alexander the Great - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Alexander the Great - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Although king of ancient Macedonia for less than 13 years, Alexander the Great changed the course of history. One of the world’s greatest military generals, he created a vast empire that stretched from Macedonia to Egypt and from Greece to part of India. This allowed for Hellenistic culture to become widespread.

Alexander was the son of Philip II and Olympias (daughter of King Neoptolemus of Epirus). From age 13 to 16 he was taught by the Greek philosopher Aristotle , who inspired his interest in philosophy, medicine, and scientific investigation. As a teenager, Alexander became known for his exploits on the battlefield.

While in Babylon , Alexander became ill after a prolonged banquet and drinking bout, and on June 13, 323, he died at age 33. There was much speculation about the cause of death, and the most popular theories claim that he either contracted malaria or typhoid fever or that he was poisoned.

While he could be ruthless and impulsive, Alexander was also charismatic and sensible. His troops were extremely loyal, believing in him throughout all hardships. Hugely ambitious, Alexander drew inspiration from the gods Achilles , Heracles , and Dionysus . He also displayed a deep interest in learning and encouraged the spread of Hellenistic culture.

Alexander the Great (born 356 bce , Pella, Macedonia [northwest of Thessaloníki, Greece]—died June 13, 323 bce , Babylon [near Al-Ḥillah, Iraq]) was the king of Macedonia (336–323 bce ), who overthrew the Persian empire , carried Macedonian arms to India , and laid the foundations for the Hellenistic world of territorial kingdoms. Already in his lifetime the subject of fabulous stories, he later became the hero of a full-scale legend bearing only the sketchiest resemblance to his historical career.

He was born in 356 bce at Pella in Macedonia, the son of Philip II and Olympias (daughter of King Neoptolemus of Epirus ). From age 13 to 16 he was taught by Aristotle , who inspired him with an interest in philosophy , medicine , and scientific investigation , but he was later to advance beyond his teacher’s narrow precept that non-Greeks should be treated as slaves. Left in charge of Macedonia in 340 during Philip’s attack on Byzantium , Alexander defeated the Maedi, a Thracian people. Two years later he commanded the left wing at the Battle of Chaeronea , in which Philip defeated the allied Greek states, and displayed personal courage in breaking the Sacred Band of Thebes , an elite military corps composed of 150 pairs of lovers. A year later Philip divorced Olympias, and, after a quarrel at a feast held to celebrate his father’s new marriage, Alexander and his mother fled to Epirus, and Alexander later went to Illyria . Shortly afterward, father and son were reconciled and Alexander returned, but his position as heir was jeopardized.

In 336, however, on Philip’s assassination , Alexander, acclaimed by the army, succeeded without opposition. He at once executed the princes of Lyncestis, alleged to be behind Philip’s murder, along with all possible rivals and the whole of the faction opposed to him. He then marched south, recovered a wavering Thessaly , and at an assembly of the Greek League of Corinth was appointed generalissimo for the forthcoming invasion of Asia , already planned and initiated by Philip. Returning to Macedonia by way of Delphi (where the Pythian priestess acclaimed him “invincible”), he advanced into Thrace in spring 335 and, after forcing the Shipka Pass and crushing the Triballi , crossed the Danube to disperse the Getae ; turning west, he then defeated and shattered a coalition of Illyrians who had invaded Macedonia. Meanwhile, a rumour of his death had precipitated a revolt of Theban democrats; other Greek states favoured Thebes , and the Athenians , urged on by Demosthenes , voted help. In 14 days Alexander marched 240 miles from Pelion (near modern Korçë , Albania ) in Illyria to Thebes. When the Thebans refused to surrender, he made an entry and razed their city to the ground, sparing only temples and Pindar ’s house; 6,000 were killed and all survivors sold into slavery . The other Greek states were cowed by this severity, and Alexander could afford to treat Athens leniently. Macedonian garrisons were left in Corinth , Chalcis , and the Cadmea (the citadel of Thebes).

From his accession Alexander had set his mind on the Persian expedition . He had grown up to the idea. Moreover, he needed the wealth of Persia if he was to maintain the army built by Philip and pay off the 500 talents he owed. The exploits of the Ten Thousand, Greek soldiers of fortune, and of Agesilaus of Sparta , in successfully campaigning in Persian territory had revealed the vulnerability of the Persian empire . With a good cavalry force Alexander could expect to defeat any Persian army. In spring 334 he crossed the Dardanelles , leaving Antipater , who had already faithfully served his father, as his deputy in Europe with over 13,000 men; he himself commanded about 30,000 foot and over 5,000 cavalry, of whom nearly 14,000 were Macedonians and about 7,000 allies sent by the Greek League. This army was to prove remarkable for its balanced combination of arms. Much work fell on the lightarmed Cretan and Macedonian archers, Thracians, and the Agrianian javelin men. But in pitched battle the striking force was the cavalry , and the core of the army, should the issue still remain undecided after the cavalry charge, was the infantry phalanx , 9,000 strong, armed with 13-foot spears and shields, and the 3,000 men of the royal battalions, the hypaspists. Alexander’s second in command was Parmenio , who had secured a foothold in Asia Minor during Philip’s lifetime; many of his family and supporters were entrenched in positions of responsibility. The army was accompanied by surveyors, engineers, architects, scientists, court officials, and historians; from the outset Alexander seems to have envisaged an unlimited operation.

After visiting Ilium ( Troy ), a romantic gesture inspired by Homer , he confronted his first Persian army, led by three satraps , at the Granicus (modern Kocabaş) River, near the Sea of Marmara (May/June 334). The Persian plan to tempt Alexander across the river and kill him in the melee almost succeeded; but the Persian line broke, and Alexander’s victory was complete. Darius ’s Greek mercenaries were largely massacred, but 2,000 survivors were sent back to Macedonia in chains. This victory exposed western Asia Minor to the Macedonians, and most cities hastened to open their gates. The tyrants were expelled and (in contrast to Macedonian policy in Greece) democracies were installed. Alexander thus underlined his Panhellenic policy, already symbolized in the sending of 300 panoplies (sets of armour) taken at the Granicus as an offering dedicated to Athena at Athens by “Alexander son of Philip and the Greeks (except the Spartans) from the barbarians who inhabit Asia.” (This formula, cited by the Greek historian Arrian in his history of Alexander’s campaigns, is noteworthy for its omission of any reference to Macedonia.) But the cities remained de facto under Alexander, and his appointment of Calas as satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia reflected his claim to succeed the Great King of Persia. When Miletus , encouraged by the proximity of the Persian fleet, resisted, Alexander took it by assault, but, refusing a naval battle, he disbanded his own costly navy and announced that he would “defeat the Persian fleet on land,” by occupying the coastal cities. In Caria , Halicarnassus resisted and was stormed, but Ada , the widow and sister of the satrap Idrieus, adopted Alexander as her son and, after expelling her brother Pixodarus, Alexander restored her to her satrapy. Some parts of Caria held out, however, until 332.

In winter 334–333 Alexander conquered western Asia Minor, subduing the hill tribes of Lycia and Pisidia , and in spring 333 he advanced along the coastal road to Perga , passing the cliffs of Mount Climax, thanks to a fortunate change of wind. The fall in the level of the sea was interpreted as a mark of divine favour by Alexander’s flatterers, including the historian Callisthenes . At Gordium in Phrygia , tradition records his cutting of the Gordian knot , which could only be loosed by the man who was to rule Asia; but this story may be apocryphal or at least distorted. At this point Alexander benefitted from the sudden death of Memnon , the competent Greek commander of the Persian fleet. From Gordium he pushed on to Ancyra (modern Ankara ) and thence south through Cappadocia and the Cilician Gates (modern Külek Boğazi); a fever held him up for a time in Cilicia . Meanwhile, Darius with his Grand Army had advanced northward on the eastern side of Mount Amanus. Intelligence on both sides was faulty, and Alexander was already encamped by Myriandrus (near modern İskenderun , Turkey ) when he learned that Darius was astride his line of communications at Issus , north of Alexander’s position (autumn 333). Turning, Alexander found Darius drawn up along the Pinarus River. In the battle that followed, Alexander won a decisive victory. The struggle turned into a Persian rout and Darius fled, leaving his family in Alexander’s hands; the women were treated with chivalrous care.

From Issus Alexander marched south into Syria and Phoenicia , his object being to isolate the Persian fleet from its bases and so to destroy it as an effective fighting force. The Phoenician cities Marathus and Aradus came over quietly, and Parmenio was sent ahead to secure Damascus and its rich booty, including Darius ’s war chest. In reply to a letter from Darius offering peace, Alexander replied arrogantly, recapitulating the historic wrongs of Greece and demanding unconditional surrender to himself as lord of Asia. After taking Byblos (modern Jubayl) and Sidon (Arabic Ṣaydā), he met with a check at Tyre , where he was refused entry into the island city. He thereupon prepared to use all methods of siegecraft to take it, but the Tyrians resisted, holding out for seven months. In the meantime (winter 333–332) the Persians had counterattacked by land in Asia Minor—where they were defeated by Antigonus , the satrap of Greater Phrygia—and by sea, recapturing a number of cities and islands.

While the siege of Tyre was in progress, Darius sent a new offer: he would pay a huge ransom of 10,000 talents for his family and cede all his lands west of the Euphrates . “I would accept,” Parmenio is reported to have said, “were I Alexander”; “I too,” was the famous retort, “were I Parmenio.” The storming of Tyre in July 332 was Alexander’s greatest military achievement; it was attended with great carnage and the sale of the women and children into slavery . Leaving Parmenio in Syria, Alexander advanced south without opposition until he reached Gaza on its high mound; there bitter resistance halted him for two months, and he sustained a serious shoulder wound during a sortie. There is no basis for the tradition that he turned aside to visit Jerusalem .

In November 332 he reached Egypt . The people welcomed him as their deliverer, and the Persian satrap Mazaces wisely surrendered. At Memphis Alexander sacrificed to Apis , the Greek term for Hapi, the sacred Egyptian bull, and was crowned with the traditional double crown of the pharaohs ; the native priests were placated and their religion encouraged. He spent the winter organizing Egypt , where he employed Egyptian governors, keeping the army under a separate Macedonian command. He founded the city of Alexandria near the western arm of the Nile on a fine site between the sea and Lake Mareotis, protected by the island of Pharos, and had it laid out by the Rhodian architect Deinocrates. He is also said to have sent an expedition to discover the causes of the flooding of the Nile. From Alexandria he marched along the coast to Paraetonium and from there inland to visit the celebrated oracle of the god Amon (at Sīwah ); the difficult journey was later embroidered with flattering legends . On his reaching the oracle in its oasis , the priest gave him the traditional salutation of a pharaoh , as son of Amon; Alexander consulted the god on the success of his expedition but revealed the reply to no one. Later the incident was to contribute to the story that he was the son of Zeus and, thus, to his “deification.” In spring 331 he returned to Tyre, appointed a Macedonian satrap for Syria, and prepared to advance into Mesopotamia . His conquest of Egypt had completed his control of the whole eastern Mediterranean coast.

In July 331 Alexander was at Thapsacus on the Euphrates . Instead of taking the direct route down the river to Babylon , he made across northern Mesopotamia toward the Tigris , and Darius, learning of this move from an advance force sent under Mazaeus to the Euphrates crossing, marched up the Tigris to oppose him. The decisive battle of the war was fought on October 31, on the plain of Gaugamela between Nineveh and Arbela. Alexander pursued the defeated Persian forces for 35 miles to Arbela, but Darius escaped with his Bactrian cavalry and Greek mercenaries into Media .

Alexander now occupied Babylon , city and province; Mazaeus, who surrendered it, was confirmed as satrap in conjunction with a Macedonian troop commander, and quite exceptionally was granted the right to coin . As in Egypt, the local priesthood was encouraged. Susa , the capital, also surrendered, releasing huge treasures amounting to 50,000 gold talents; here Alexander established Darius’s family in comfort. Crushing the mountain tribe of the Ouxians, he now pressed on over the Zagros range into Persia proper and, successfully turning the Pass of the Persian Gates, held by the satrap Ariobarzanes , he entered Persepolis and Pasargadae . At Persepolis he ceremonially burned down the palace of Xerxes , as a symbol that the Panhellenic war of revenge was at an end; for such seems the probable significance of an act that tradition later explained as a drunken frolic inspired by Thaïs , an Athenian courtesan. In spring 330 Alexander marched north into Media and occupied its capital. The Thessalians and Greek allies were sent home; henceforward he was waging a purely personal war.

As Mazaeus’s appointment indicated, Alexander’s views on the empire were changing. He had come to envisage a joint ruling people consisting of Macedonians and Persians, and this served to augment the misunderstanding that now arose between him and his people. Before continuing his pursuit of Darius, who had retreated into Bactria , he assembled all the Persian treasure and entrusted it to Harpalus , who was to hold it at Ecbatana as chief treasurer. Parmenio was also left behind in Media to control communications; the presence of this older man had perhaps become irksome.

In midsummer 330 Alexander set out for the eastern provinces at a high speed via Rhagae (modern Rayy , near Tehrān ) and the Caspian Gates, where he learned that Bessus , the satrap of Bactria, had deposed Darius. After a skirmish near modern Shāhrūd, the usurper had Darius stabbed and left him to die. Alexander sent his body for burial with due honours in the royal tombs at Persepolis.

Darius ’s death left no obstacle to Alexander’s claim to be Great King, and a Rhodian inscription of this year (330) calls him “lord of Asia”—i.e., of the Persian empire; soon afterward his Asian coins carry the title of king. Crossing the Elburz Mountains to the Caspian , he seized Zadracarta in Hyrcania and received the submission of a group of satraps and Persian notables, some of whom he confirmed in their offices; in a diversion westward, perhaps to modern Āmol , he reduced the Mardi, a mountain people who inhabited the Elburz Mountains. He also accepted the surrender of Darius’s Greek mercenaries. His advance eastward was now rapid. In Aria he reduced Satibarzanes, who had offered submission only to revolt, and he founded Alexandria of the Arians (modern Herāt ). At Phrada in Drangiana (either near modern Nad-e ʿAli in Seistan or farther north at Farah ), he at last took steps to destroy Parmenio and his family. Philotas , Parmenio’s son, commander of the elite Companion cavalry, was implicated in an alleged plot against Alexander’s life, condemned by the army, and executed; and a secret message was sent to Cleander , Parmenio’s second in command, who obediently assassinated him. This ruthless action excited widespread horror but strengthened Alexander’s position relative to his critics and those whom he regarded as his father’s men. All Parmenio’s adherents were now eliminated and men close to Alexander promoted. The Companion cavalry was reorganized in two sections, each containing four squadrons (now known as hipparchies); one group was commanded by Alexander’s oldest friend, Hephaestion , the other by Cleitus , an older man. From Phrada, Alexander pressed on during the winter of 330–329 up the valley of the Helmand River , through Arachosia , and over the mountains past the site of modern Kābul into the country of the Paropamisadae, where he founded Alexandria by the Caucasus .

Bessus was now in Bactria raising a national revolt in the eastern satrapies with the usurped title of Great King. Crossing the Hindu Kush northward over the Khawak Pass (11,650 feet [3,550 metres]), Alexander brought his army, despite food shortages, to Drapsaca (sometimes identified with modern Banu [Andarab], probably farther north at Qunduz); outflanked, Bessus fled beyond the Oxus (modern Amu Darya ), and Alexander, marching west to Bactra-Zariaspa (modern Balkh [ Wazirabad ] in Afghanistan ), appointed loyal satraps in Bactria and Aria. Crossing the Oxus, he sent his general Ptolemy in pursuit of Bessus, who had meanwhile been overthrown by the Sogdian Spitamenes. Bessus was captured, flogged, and sent to Bactra, where he was later mutilated after the Persian manner (losing his nose and ears); in due course he was publicly executed at Ecbatana .

From Maracanda (modern Samarkand ) Alexander advanced by way of Cyropolis to the Jaxartes (modern Syrdarya), the boundary of the Persian empire. There he broke the opposition of the Scythian nomads by his use of catapults and, after defeating them in a battle on the north bank of the river, pursued them into the interior. On the site of modern Leninabad ( Khojent ) on the Jaxartes, he founded a city, Alexandria Eschate, “the farthest.” Meanwhile, Spitamenes had raised all Sogdiana in revolt behind him, bringing in the Massagetai , a people of the Shaka confederacy. It took Alexander until the autumn of 328 to crush the most determined opponent he encountered in his campaigns. Later in the same year he attacked Oxyartes and the remaining barons who held out in the hills of Paraetacene (modern Tajikistan ); volunteers seized the crag on which Oxyartes had his stronghold, and among the captives was his daughter, Roxana . In reconciliation Alexander married her, and the rest of his opponents were either won over or crushed.

An incident that occurred at Maracanda widened the breach between Alexander and many of his Macedonians. He murdered Cleitus, one of his most-trusted commanders, in a drunken quarrel, but his excessive display of remorse led the army to pass a decree convicting Cleitus posthumously of treason . The event marked a step in Alexander’s progress toward Eastern absolutism, and this growing attitude found its outward expression in his use of Persian royal dress. Shortly afterward, at Bactra , he attempted to impose the Persian court ceremonial, involving prostration ( proskynesis ), on the Greeks and Macedonians too, but to them this custom, habitual for Persians entering the king’s presence, implied an act of worship and was intolerable before a human. Even Callisthenes , historian and nephew of Aristotle , whose ostentatious flattery had perhaps encouraged Alexander to see himself in the role of a god, refused to abase himself. Macedonian laughter caused the experiment to founder, and Alexander abandoned it. Shortly afterward, however, Callisthenes was held to be privy to a conspiracy among the royal pages and was executed (or died in prison; accounts vary); resentment of this action alienated sympathy from Alexander within the Peripatetic school of philosophers, with which Callisthenes had close connections.

In early summer 327 Alexander left Bactria with a reinforced army under a reorganized command. If Plutarch ’s figure of 120,000 men has any reality, however, it must include all kinds of auxiliary services, together with muleteers, camel drivers, medical corps, peddlers, entertainers, women, and children; the fighting strength perhaps stood at about 35,000. Recrossing the Hindu Kush , probably by Bamiyan and the Ghorband Valley, Alexander divided his forces. Half the army with the baggage under Hephaestion and Perdiccas , both cavalry commanders, was sent through the Khyber Pass , while he himself led the rest, together with his siege train, through the hills to the north. His advance through Swāt and Gandhāra was marked by the storming of the almost impregnable pinnacle of Aornos , the modern Pir-Sar, a few miles west of the Indus and north of the Buner River, an impressive feat of siegecraft. In spring 326, crossing the Indus near Attock, Alexander entered Taxila , whose ruler, Taxiles, furnished elephants and troops in return for aid against his rival Porus , who ruled the lands between the Hydaspes (modern Jhelum ) and the Acesines (modern Chenāb ). In June Alexander fought his last great battle on the left bank of the Hydaspes . He founded two cities there, Alexandria Nicaea (to celebrate his victory) and Bucephala (named after his horse Bucephalus , which died there); and Porus became his ally.

How much Alexander knew of India beyond the Hyphasis (probably the modern Beas ) is uncertain; there is no conclusive proof that he had heard of the Ganges . But he was anxious to press on farther, and he had advanced to the Hyphasis when his army mutinied, refusing to go farther in the tropical rain; they were weary in body and spirit, and Coenus, one of Alexander’s four chief marshals, acted as their spokesman. On finding the army adamant , Alexander agreed to turn back.

On the Hyphasis he erected 12 altars to the 12 Olympian gods, and on the Hydaspes he built a fleet of 800 to 1,000 ships. Leaving Porus, he then proceeded down the river and into the Indus, with half his forces on shipboard and half marching in three columns down the two banks. The fleet was commanded by Nearchus , and Alexander’s own captain was Onesicritus; both later wrote accounts of the campaign. The march was attended with much fighting and heavy, pitiless slaughter; at the storming of one town of the Malli near the Hydraotes ( Ravi ) River, Alexander received a severe wound which left him weakened.

On reaching Patala, located at the head of the Indus delta, he built a harbour and docks and explored both arms of the Indus, which probably then ran into the Rann of Kachchh . He planned to lead part of his forces back by land, while the rest in perhaps 100 to 150 ships under the command of Nearchus, a Cretan with naval experience, made a voyage of exploration along the Persian Gulf . Local opposition led Nearchus to set sail in September (325), and he was held up for three weeks until he could pick up the northeast monsoon in late October. In September Alexander too set out along the coast through Gedrosia (modern Baluchistan), but he was soon compelled by mountainous country to turn inland, thus failing in his project to establish food depots for the fleet. Craterus , a high-ranking officer, already had been sent off with the baggage and siege train, the elephants, and the sick and wounded, together with three battalions of the phalanx , by way of the Mulla Pass, Quetta , and Kandahar into the Helmand Valley ; from there he was to march through Drangiana to rejoin the main army on the Amanis (modern Minab) River in Carmania. Alexander’s march through Gedrosia proved disastrous; waterless desert and shortage of food and fuel caused great suffering, and many, especially women and children, perished in a sudden monsoon flood while encamped in a wadi. At length, at the Amanis, he was rejoined by Nearchus and the fleet, which also had suffered losses.

Alexander now proceeded farther with the policy of replacing senior officials and executing defaulting governors on which he had already embarked before leaving India. Between 326 and 324 over a third of his satraps were superseded and six were put to death, including the Persian satraps of Persis , Susiana, Carmania, and Paraetacene; three generals in Media , including Cleander , the brother of Coenus (who had died a little earlier), were accused of extortion and summoned to Carmania, where they were arrested, tried, and executed. How far the rigour that from now onward Alexander displayed against his governors represents exemplary punishment for gross maladministration during his absence and how far the elimination of men he had come to distrust (as in the case of Philotas and Parmenio ) is debatable; but the ancient sources generally favourable to him comment adversely on his severity.

In spring 324 he was back in Susa , capital of Elam and administrative centre of the Persian empire; the story of his journey through Carmania in a drunken revel, dressed as Dionysus , is embroidered, if not wholly apocryphal. He found that his treasurer, Harpalus , evidently fearing punishment for peculation, had absconded with 6,000 mercenaries and 5,000 talents to Greece; arrested in Athens , he escaped and later was murdered in Crete . At Susa Alexander held a feast to celebrate the seizure of the Persian empire, at which, in furtherance of his policy of fusing Macedonians and Persians into one master race, he and 80 of his officers took Persian wives; he and Hephaestion married Darius ’s daughters Barsine (also called Stateira) and Drypetis, respectively, and 10,000 of his soldiers with native wives were given generous dowries.

This policy of racial fusion brought increasing friction to Alexander’s relations with his Macedonians, who had no sympathy for his changed concept of the empire. His determination to incorporate Persians on equal terms in the army and the administration of the provinces was bitterly resented. This discontent was now fanned by the arrival of 30,000 native youths who had received a Macedonian military training and by the introduction of Asian peoples from Bactria , Sogdiana , Arachosia , and other parts of the empire into the Companion cavalry ; whether Asians had previously served with the Companions is uncertain, but if so they must have formed separate squadrons. In addition, Persian nobles had been accepted into the royal cavalry bodyguard. Peucestas, the new governor of Persis , gave this policy full support to flatter Alexander; but most Macedonians saw it as a threat to their own privileged position.

The issue came to a head at Opis (324), when Alexander’s decision to send home Macedonian veterans under Craterus was interpreted as a move toward transferring the seat of power to Asia. There was an open mutiny involving all but the royal bodyguard; but when Alexander dismissed his whole army and enrolled Persians instead, the opposition broke down. An emotional scene of reconciliation was followed by a vast banquet with 9,000 guests to celebrate the ending of the misunderstanding and the partnership in government of Macedonians and Persians—but not, as has been argued, the incorporation of all the subject peoples as partners in the commonwealth. Ten thousand veterans were now sent back to Macedonia with gifts, and the crisis was surmounted.

In summer 324 Alexander attempted to solve another problem, that of the wandering mercenaries, of whom there were thousands in Asia and Greece, many of them political exiles from their own cities. A decree brought by Nicanor to Europe and proclaimed at Olympia (September 324) required the Greek cities of the Greek League to receive back all exiles and their families (except the Thebans), a measure that implied some modification of the oligarchic regimes maintained in the Greek cities by Alexander’s governor Antipater . Alexander now planned to recall Antipater and supersede him by Craterus , but he was to die before this could be done.

In autumn 324 Hephaestion died in Ecbatana , and Alexander indulged in extravagant mourning for his closest friend; he was given a royal funeral in Babylon with a pyre costing 10,000 talents. His post of chiliarch (grand vizier) was left unfilled. It was probably in connection with a general order now sent out to the Greeks to honour Hephaestion as a hero that Alexander linked the demand that he himself should be accorded divine honours. For a long time his mind had dwelt on ideas of godhead. Greek thought drew no very decided line of demarcation between god and man, for legend offered more than one example of men who, by their achievements, acquired divine status. Alexander had on several occasions encouraged favourable comparison of his own accomplishments with those of Dionysus or Heracles . He now seems to have become convinced of the reality of his own divinity and to have required its acceptance by others. There is no reason to assume that his demand had any political background (divine status gave its possessor no particular rights in a Greek city); it was rather a symptom of growing megalomania and emotional instability. The cities perforce complied, but often ironically: the Spartan decree read, “Since Alexander wishes to be a god, let him be a god.”

In the winter of 324 Alexander carried out a savage punitive expedition against the Cossaeans in the hills of Luristan. The following spring at Babylon he received complimentary embassies from the Libyans and from the Bruttians, Etruscans , and Lucanians of Italy; but the story that embassies also came from more distant peoples, such as Carthaginians, Celts , Iberians , and even Romans, is a later invention. Representatives of the cities of Greece also came, garlanded as befitted Alexander’s divine status. Following up Nearchus’s voyage , he now founded an Alexandria at the mouth of the Tigris and made plans to develop sea communications with India, for which an expedition along the Arabian coast was to be a preliminary. He also dispatched Heracleides, an officer, to explore the Hyrcanian (i.e., Caspian ) Sea. Suddenly, in Babylon , while busy with plans to improve the irrigation of the Euphrates and to settle the coast of the Persian Gulf , Alexander was taken ill after a prolonged banquet and drinking bout; 10 days later, on June 13, 323, he died in his 33rd year; he had reigned for 12 years and eight months. His body, diverted to Egypt by Ptolemy , the later king, was eventually placed in a golden coffin in Alexandria . Both in Egypt and elsewhere in the Greek cities he received divine honours.

No heir had been appointed to the throne, and his generals adopted Philip II ’s half-witted illegitimate son, Philip Arrhidaeus , and Alexander’s posthumous son by Roxana, Alexander IV , as kings, sharing out the satrapies among themselves, after much bargaining. The empire could hardly survive Alexander’s death as a unit. Both kings were murdered, Arrhidaeus in 317 and Alexander in 310/309. The provinces became independent kingdoms, and the generals , following Antigonus ’s lead in 306, took the title of king.

Alexander The Great - List of Free Essay Examples And Topic Ideas

Alexander the Great was a historical figure known for his military prowess and the creation of one of the largest empires in ancient history. Essays on Alexander the Great could explore his life, campaigns, and strategies, his impact on the cultures and regions he conquered, and his lasting legacy. Discussions might also include assessments of his leadership and analyses of historical and contemporary interpretations of his actions and achievements. A substantial compilation of free essay instances related to Alexander The Great you can find in Papersowl database. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Was Alexander the Great Really “Great”?

Alexander the great once said, “I am not afraid of an army of lions led by a sheep; I am afraid of an army of sheep led by a lion.” This quote from Alexander shows his leadership knowledge. He knew what it took to be a great leader who lead his army on the front line afraid of nothing. Although Alexander the great caused over 100,000 people to die and was very greedy but, he is still one of the […]

Alexander the Great, a Great General but not so Great of and Administrator

Many have argued that Alexander III of Macedon (356 BC-323 BC) commonly known as Alexander the Great, that the collapse of his empire was caused primarily by his death, however the primary cause of collapse of his empire was his failure to lead and administer the state. For it is this which is the most notable result of Alexander's life and work; for all his military prowess, he was one of the world's greatest failures""and that failure spelt misery and […]

Alexander III of Macedon

Alexander III of Macedon made a impact on his people. Alexander the great earned his title as the great. He achieved many things in his life. A lot of people still remember him after he passed. He did a lot for his people. He was king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He was born in Pella in 356 BC. He was smart and great opportunities being a prince to learn from the best smartest people. He showed that […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Alexander the Great – King of Macedonia and Ancient Greece

Who is Alexander the Great? Alexander the Great is was the king of Macedonia and Ancient Greece. He may be known as the greatest military commander in history. Alexander the Great was born July 20, 356 BC. Alexander died at a very young age at 32. At a young age he accomplished a lot of things in his short life. Alexander's accomplishments was to do so much in his lifetime even thought it was such a lasting affect to him. […]

Alexander the Great Biography

Born on September 20, 356 B.C. and tutored by the one and only Aristotle at a young age. Alexander took control over nearly all of the eastern Mediterranean countries within 11 years of his life. Before his father's death in 338 B.C., he and his father conducted the Companion Cavalry and helped him demolish the Athenian and Theban Forces of Chaeronea. With such history of crumbling empires from his father Phillip, Alexander continued his fathers deeds with skills off and […]

Alexander: Brave and Successful Leader

By the time Alexander was thirty-two, he ruled the largest western empire of the ancient world. He once said ""toil and risk are the prices of glory, but it is a lovely thing to live with courage and die leaving an everlasting fame"". Alexander was a very brave and successful leader whose strategies were skillful and imaginative. His use of cavalry was so effective that he rarely had to fall back upon his infantry to deliver the crushing below. He […]

Alexander the Great was One of the Greatest Leaders

In this paper I will be covering his early life, what he did while he was ruling and what happened to Rome after he died. Alexander the Great was born in the Pella Region, located in Macedonia, on July 20, 356 B.C. to parents King Phillip II and Queen Olympia. Alexander and his sister were raised in Pella's royal court. Alexander's father was not a big part of his life, King Phillip spent most of his time in military campaigns. […]

Alexander the Great the Gleaming Pearl of Ancient Greece

In the history of the ancient world, there are outstanding leaders with strategic minds and the ability to defeat all enemies. Among the most talented kings in the world, the most important one is probably Alexander the Great. Alexander the Great (356 - 323 BC) was the emperor who crushed the mighty Persian Empire and built the Greek Empire. He was a natural military genius and also considered to be a great contributor to the development of the history of […]

Who is Alexander the Great?

Alexander the Great accumulated the largest empire in the ancient world in about thirteen years. His empire was over 3000 miles wide. In the end of his conquest his empire spanned from Macedonia all the way to India and the Indus River Valley. (""Alexander the Great."") Alexander the Great was born in 356 BC. to his father Philip II, king of Macedonia. As he grew up he watched his father turn Macedonia into a strong military power. When Alexander was […]

Macedonia: Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great was born in 356 B.C, and was the son of King Philip II of Macedonia. He was born in the city of Pella. According to legend, Alexander's real father was Zeus. Philip was often away at war, so Alexander rarely saw his father. His mother, Olympias, may also have instilled in him a resentment of his father. By the age of twelve, Alexander had tamed a wild horse named Bucephalus. For the majority of Alexander's life, the […]

Conquests of Alexander the Great

Alexander was set up to succeed his dad Philip II through watchful direction. When his dad kicked the bucket, he had mentored him from multiple points of view and he had additionally set the ground for his successes. Alexander acquired a urbanized people, an efficient military, and philosophical and military training and he used his insight to vanquish Persia and different parts of Asia. His heritage comprised of his despotic governments and utilization of military power as a major aspect […]

Alexander the Great: Conquests, Legacy, and Influence

In the annals of history, few names resonate with as much power and prestige as that of Alexander the Great. Born in 356 BC in Pella, the ancient capital of Macedonia, Alexander ascended to the throne at the tender age of 20, inheriting a kingdom on the cusp of greatness. What followed was a whirlwind of conquests, a relentless march across continents, and a legacy that would shape the course of civilizations for centuries to come. From the outset, Alexander's […]

Understanding why Alexander the Great was Truly Great

In the chronicles of history, few figures echo with the same resounding significance as Alexander the Great. Born in 356 BCE in the ancient kingdom of Macedon, Alexander would rise to forge an empire that extended from Greece to Egypt and from Persia to the frontiers of India. His conquests were the stuff of legends, his ambition unparalleled, and his legacy enduring. But what truly made Alexander the Great live up to his name? At the core of Alexander's greatness […]

The Birthplace of Cleopatra: a Historical Examination

Cleopatra VII Philopator, the final sovereign of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, remains a captivating historical figure enveloped in mystery and fascination. Her birthplace, a topic less explored than her reign or political alliances, presents an engaging perspective on her formative years and the setting that influenced her. This essay delves into the historical backdrop of Cleopatra’s birthplace, exploring its impact and the circumstances surrounding her early life in Alexandria, Egypt. Born in 69 BCE, Cleopatra entered the world in […]

The Birth of Alexander the Great: a Historical Inquiry

In the annals of history, few figures loom as large and enduring as Alexander the Great. His name evokes images of conquest, empire, and the spread of Hellenistic culture across vast swathes of the ancient world. Yet, amidst the legends and myths that surround his life, one question stands out as fundamental: when was Alexander the Great born? The birth of Alexander is a matter of historical debate, shrouded in the mists of time and complicated by conflicting accounts from […]

| Full name : | Alexander III of Macedon |

| Spouse : | Roxana (m. 327 BC–323 BC), Stateira II (m. 324 BC–323 BC), Parysatis II (m. 324 BC–323 BC) |

| Children : | Alexander IV of Macedon, Heracles of Macedon |

| Parents : | Philip II of Macedon, Olympias |

| Nationality : | Greek, Macedonian |

Additional Example Essays

- Letter From Birmingham Jail Rhetorical Analysis

- Followership and Servant Leadership

- Martin Luther King vs Malcolm X

- Analysis of Letter from Birmingham Jail

- Rosa Parks Vs. Harriet Tubman

- Martin Luther King Speech Evaluation

- Martin Luther King as Activist and Outsider

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

- Bob Marley as the most influential artists

- Pathos in "I Have a Dream" Speech by Martin Luther King Jr.

- Frederick Douglass' Sucesses, Failures, and Consequences

- Compare And Contrast In WW1 And WW2

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.14(4); 2022 Apr

Historical Perspective and Medical Maladies of Alexander the Great

Shri k mishra.

1 Neurology, Olive View - University of California Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, USA

2 Neurology, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA

Adam Mengestab

3 Neurology, Scripps College, Claremont, USA

Shaweta Khosa