Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is the Background of a Study and How to Write It (Examples Included)

Have you ever found yourself struggling to write a background of the study for your research paper? You’re not alone. While the background of a study is an essential element of a research manuscript, it’s also one of the most challenging pieces to write. This is because it requires researchers to provide context and justification for their research, highlight the significance of their study, and situate their work within the existing body of knowledge in the field.

Despite its challenges, the background of a study is crucial for any research paper. A compelling well-written background of the study can not only promote confidence in the overall quality of your research analysis and findings, but it can also determine whether readers will be interested in knowing more about the rest of the research study.

In this article, we’ll explore the key elements of the background of a study and provide simple guidelines on how to write one effectively. Whether you’re a seasoned researcher or a graduate student working on your first research manuscript, this post will explain how to write a background for your study that is compelling and informative.

Table of Contents

What is the background of a study ?

Typically placed in the beginning of your research paper, the background of a study serves to convey the central argument of your study and its significance clearly and logically to an uninformed audience. The background of a study in a research paper helps to establish the research problem or gap in knowledge that the study aims to address, sets the stage for the research question and objectives, and highlights the significance of the research. The background of a study also includes a review of relevant literature, which helps researchers understand where the research study is placed in the current body of knowledge in a specific research discipline. It includes the reason for the study, the thesis statement, and a summary of the concept or problem being examined by the researcher. At times, the background of a study can may even examine whether your research supports or contradicts the results of earlier studies or existing knowledge on the subject.

How is the background of a study different from the introduction?

It is common to find early career researchers getting confused between the background of a study and the introduction in a research paper. Many incorrectly consider these two vital parts of a research paper the same and use these terms interchangeably. The confusion is understandable, however, it’s important to know that the introduction and the background of the study are distinct elements and serve very different purposes.

- The basic different between the background of a study and the introduction is kind of information that is shared with the readers . While the introduction provides an overview of the specific research topic and touches upon key parts of the research paper, the background of the study presents a detailed discussion on the existing literature in the field, identifies research gaps, and how the research being done will add to current knowledge.

- The introduction aims to capture the reader’s attention and interest and to provide a clear and concise summary of the research project. It typically begins with a general statement of the research problem and then narrows down to the specific research question. It may also include an overview of the research design, methodology, and scope. The background of the study outlines the historical, theoretical, and empirical background that led to the research question to highlight its importance. It typically offers an overview of the research field and may include a review of the literature to highlight gaps, controversies, or limitations in the existing knowledge and to justify the need for further research.

- Both these sections appear at the beginning of a research paper. In some cases the introduction may come before the background of the study , although in most instances the latter is integrated into the introduction itself. The length of the introduction and background of a study can differ based on the journal guidelines and the complexity of a specific research study.

Learn to convey study relevance, integrate literature reviews, and articulate research gaps in the background section. Get your All Access Pack now!

To put it simply, the background of the study provides context for the study by explaining how your research fills a research gap in existing knowledge in the field and how it will add to it. The introduction section explains how the research fills this gap by stating the research topic, the objectives of the research and the findings – it sets the context for the rest of the paper.

Where is the background of a study placed in a research paper?

T he background of a study is typically placed in the introduction section of a research paper and is positioned after the statement of the problem. Researchers should try and present the background of the study in clear logical structure by dividing it into several sections, such as introduction, literature review, and research gap. This will make it easier for the reader to understand the research problem and the motivation for the study.

So, when should you write the background of your study ? It’s recommended that researchers write this section after they have conducted a thorough literature review and identified the research problem, research question, and objectives. This way, they can effectively situate their study within the existing body of knowledge in the field and provide a clear rationale for their research.

Creating an effective background of a study structure

Given that the purpose of writing the background of your study is to make readers understand the reasons for conducting the research, it is important to create an outline and basic framework to work within. This will make it easier to write the background of the study and will ensure that it is comprehensive and compelling for readers.

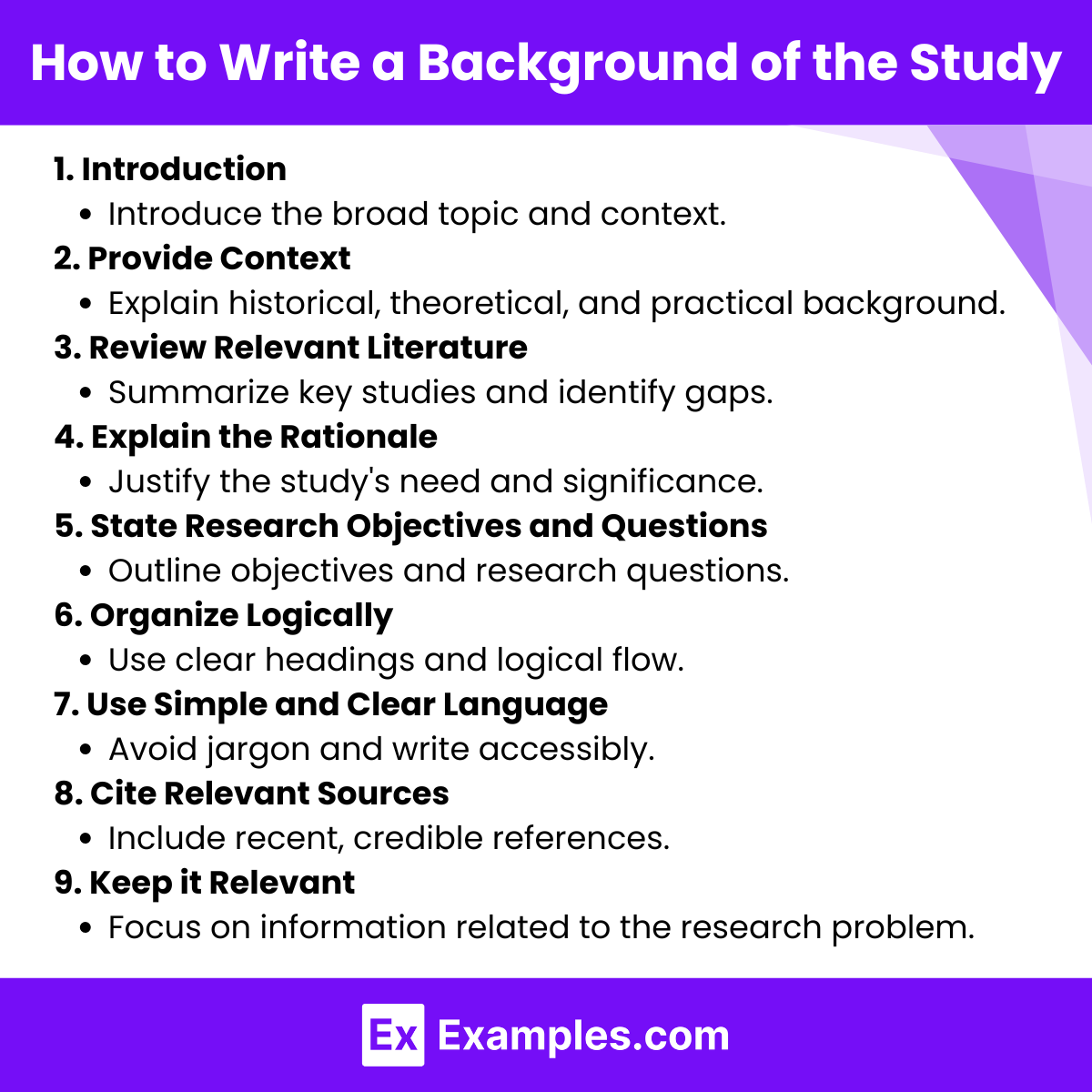

While creating a background of the study structure for research papers, it is crucial to have a clear understanding of the essential elements that should be included. Make sure you incorporate the following elements in the background of the study section :

- Present a general overview of the research topic, its significance, and main aims; this may be like establishing the “importance of the topic” in the introduction.

- Discuss the existing level of research done on the research topic or on related topics in the field to set context for your research. Be concise and mention only the relevant part of studies, ideally in chronological order to reflect the progress being made.

- Highlight disputes in the field as well as claims made by scientists, organizations, or key policymakers that need to be investigated. This forms the foundation of your research methodology and solidifies the aims of your study.

- Describe if and how the methods and techniques used in the research study are different from those used in previous research on similar topics.

By including these critical elements in the background of your study , you can provide your readers with a comprehensive understanding of your research and its context.

How to write a background of the study in research papers ?

Now that you know the essential elements to include, it’s time to discuss how to write the background of the study in a concise and interesting way that engages audiences. The best way to do this is to build a clear narrative around the central theme of your research so that readers can grasp the concept and identify the gaps that the study will address. While the length and detail presented in the background of a study could vary depending on the complexity and novelty of the research topic, it is imperative to avoid wordiness. For research that is interdisciplinary, mentioning how the disciplines are connected and highlighting specific aspects to be studied helps readers understand the research better.

While there are different styles of writing the background of a study , it always helps to have a clear plan in place. Let us look at how to write a background of study for research papers.

- Identify the research problem: Begin the background by defining the research topic, and highlighting the main issue or question that the research aims to address. The research problem should be clear, specific, and relevant to the field of study. It should be framed using simple, easy to understand language and must be meaningful to intended audiences.

- Craft an impactful statement of the research objectives: While writing the background of the study it is critical to highlight the research objectives and specific goals that the study aims to achieve. The research objectives should be closely related to the research problem and must be aligned with the overall purpose of the study.

- Conduct a review of available literature: When writing the background of the research , provide a summary of relevant literature in the field and related research that has been conducted around the topic. Remember to record the search terms used and keep track of articles that you read so that sources can be cited accurately. Ensure that the literature you include is sourced from credible sources.

- Address existing controversies and assumptions: It is a good idea to acknowledge and clarify existing claims and controversies regarding the subject of your research. For example, if your research topic involves an issue that has been widely discussed due to ethical or politically considerations, it is best to address them when writing the background of the study .

- Present the relevance of the study: It is also important to provide a justification for the research. This is where the researcher explains why the study is important and what contributions it will make to existing knowledge on the subject. Highlighting key concepts and theories and explaining terms and ideas that may feel unfamiliar to readers makes the background of the study content more impactful.

- Proofread to eliminate errors in language, structure, and data shared: Once the first draft is done, it is a good idea to read and re-read the draft a few times to weed out possible grammatical errors or inaccuracies in the information provided. In fact, experts suggest that it is helpful to have your supervisor or peers read and edit the background of the study . Their feedback can help ensure that even inadvertent errors are not overlooked.

Get exclusive discounts on e xpert-led editing to publication support with Researcher.Life’s All Access Pack. Get yours now!

How to avoid mistakes in writing the background of a study

While figuring out how to write the background of a study , it is also important to know the most common mistakes authors make so you can steer clear of these in your research paper.

- Write the background of a study in a formal academic tone while keeping the language clear and simple. Check for the excessive use of jargon and technical terminology that could confuse your readers.

- Avoid including unrelated concepts that could distract from the subject of research. Instead, focus your discussion around the key aspects of your study by highlighting gaps in existing literature and knowledge and the novelty and necessity of your study.

- Provide relevant, reliable evidence to support your claims and citing sources correctly; be sure to follow a consistent referencing format and style throughout the paper.

- Ensure that the details presented in the background of the study are captured chronologically and organized into sub-sections for easy reading and comprehension.

- Check the journal guidelines for the recommended length for this section so that you include all the important details in a concise manner.

By keeping these tips in mind, you can create a clear, concise, and compelling background of the study for your research paper. Take this example of a background of the study on the impact of social media on mental health.

Social media has become a ubiquitous aspect of modern life, with people of all ages, genders, and backgrounds using platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to connect with others, share information, and stay updated on news and events. While social media has many potential benefits, including increased social connectivity and access to information, there is growing concern about its impact on mental health. Research has suggested that social media use is associated with a range of negative mental health outcomes, including increased rates of anxiety, depression, and loneliness. This is thought to be due, in part, to the social comparison processes that occur on social media, whereby users compare their lives to the idealized versions of others that are presented online. Despite these concerns, there is also evidence to suggest that social media can have positive effects on mental health. For example, social media can provide a sense of social support and community, which can be beneficial for individuals who are socially isolated or marginalized. Given the potential benefits and risks of social media use for mental health, it is important to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying these effects. This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes, with a particular focus on the role of social comparison processes. By doing so, we hope to shed light on the potential risks and benefits of social media use for mental health, and to provide insights that can inform interventions and policies aimed at promoting healthy social media use.

To conclude, the background of a study is a crucial component of a research manuscript and must be planned, structured, and presented in a way that attracts reader attention, compels them to read the manuscript, creates an impact on the minds of readers and sets the stage for future discussions.

A well-written background of the study not only provides researchers with a clear direction on conducting their research, but it also enables readers to understand and appreciate the relevance of the research work being done.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on background of the study

Q: How does the background of the study help the reader understand the research better?

The background of the study plays a crucial role in helping readers understand the research better by providing the necessary context, framing the research problem, and establishing its significance. It helps readers:

- understand the larger framework, historical development, and existing knowledge related to a research topic

- identify gaps, limitations, or unresolved issues in the existing literature or knowledge

- outline potential contributions, practical implications, or theoretical advancements that the research aims to achieve

- and learn the specific context and limitations of the research project

Q: Does the background of the study need citation?

Yes, the background of the study in a research paper should include citations to support and acknowledge the sources of information and ideas presented. When you provide information or make statements in the background section that are based on previous studies, theories, or established knowledge, it is important to cite the relevant sources. This establishes credibility, enables verification, and demonstrates the depth of literature review you’ve done.

Q: What is the difference between background of the study and problem statement?

The background of the study provides context and establishes the research’s foundation while the problem statement clearly states the problem being addressed and the research questions or objectives.

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

What are the Best Research Funding Sources

Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Effective Background of the Study: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

The background of the study in a research paper offers a clear context, highlighting why the research is essential and the problem it aims to address.

As a researcher, this foundational section is essential for you to chart the course of your study, Moreover, it allows readers to understand the importance and path of your research.

Whether in academic communities or to the general public, a well-articulated background aids in communicating the essence of the research effectively.

While it may seem straightforward, crafting an effective background requires a blend of clarity, precision, and relevance. Therefore, this article aims to be your guide, offering insights into:

- Understanding the concept of the background of the study.

- Learning how to craft a compelling background effectively.

- Identifying and sidestepping common pitfalls in writing the background.

- Exploring practical examples that bring the theory to life.

- Enhancing both your writing and reading of academic papers.

Keeping these compelling insights in mind, let's delve deeper into the details of the empirical background of the study, exploring its definition, distinctions, and the art of writing it effectively.

What is the background of the study?

The background of the study is placed at the beginning of a research paper. It provides the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being explored.

It offers readers a snapshot of the existing knowledge on the topic and the reasons that spurred your current research.

When crafting the background of your study, consider the following questions.

- What's the context of your research?

- Which previous research will you refer to?

- Are there any knowledge gaps in the existing relevant literature?

- How will you justify the need for your current research?

- Have you concisely presented the research question or problem?

In a typical research paper structure, after presenting the background, the introduction section follows. The introduction delves deeper into the specific objectives of the research and often outlines the structure or main points that the paper will cover.

Together, they create a cohesive starting point, ensuring readers are well-equipped to understand the subsequent sections of the research paper.

While the background of the study and the introduction section of the research manuscript may seem similar and sometimes even overlap, each serves a unique purpose in the research narrative.

Difference between background and introduction

A well-written background of the study and introduction are preliminary sections of a research paper and serve distinct purposes.

Here’s a detailed tabular comparison between the two of them.

Aspect | Background | Introduction |

Primary purpose | Provides context and logical reasons for the research, explaining why the study is necessary. | Entails the broader scope of the research, hinting at its objectives and significance. |

Depth of information | It delves into the existing literature, highlighting gaps or unresolved questions that the research aims to address. | It offers a general overview, touching upon the research topic without going into extensive detail. |

Content focus | The focus is on historical context, previous studies, and the evolution of the research topic. | The focus is on the broader research field, potential implications, and a preview of the research structure. |

Position in a research paper | Typically comes at the very beginning, setting the stage for the research. | Follows the background, leading readers into the main body of the research. |

Tone | Analytical, detailing the topic and its significance. | General and anticipatory, preparing readers for the depth and direction of the focus of the study. |

What is the relevance of the background of the study?

It is necessary for you to provide your readers with the background of your research. Without this, readers may grapple with questions such as: Why was this specific research topic chosen? What led to this decision? Why is this study relevant? Is it worth their time?

Such uncertainties can deter them from fully engaging with your study, leading to the rejection of your research paper. Additionally, this can diminish its impact in the academic community, and reduce its potential for real-world application or policy influence .

To address these concerns and offer clarity, the background section plays a pivotal role in research papers.

The background of the study in research is important as it:

- Provides context: It offers readers a clear picture of the existing knowledge, helping them understand where the current research fits in.

- Highlights relevance: By detailing the reasons for the research, it underscores the study's significance and its potential impact.

- Guides the narrative: The background shapes the narrative flow of the paper, ensuring a logical progression from what's known to what the research aims to uncover.

- Enhances engagement: A well-crafted background piques the reader's interest, encouraging them to delve deeper into the research paper.

- Aids in comprehension: By setting the scenario, it aids readers in better grasping the research objectives, methodologies, and findings.

How to write the background of the study in a research paper?

The journey of presenting a compelling argument begins with the background study. This section holds the power to either captivate or lose the reader's interest.

An effectively written background not only provides context but also sets the tone for the entire research paper. It's the bridge that connects a broad topic to a specific research question, guiding readers through the logic behind the study.

But how does one craft a background of the study that resonates, informs, and engages?

Here, we’ll discuss how to write an impactful background study, ensuring your research stands out and captures the attention it deserves.

Identify the research problem

The first step is to start pinpointing the specific issue or gap you're addressing. This should be a significant and relevant problem in your field.

A well-defined problem is specific, relevant, and significant to your field. It should resonate with both experts and readers.

Here’s more on how to write an effective research problem .

Provide context

Here, you need to provide a broader perspective, illustrating how your research aligns with or contributes to the overarching context or the wider field of study. A comprehensive context is grounded in facts, offers multiple perspectives, and is relatable.

In addition to stating facts, you should weave a story that connects key concepts from the past, present, and potential future research. For instance, consider the following approach.

- Offer a brief history of the topic, highlighting major milestones or turning points that have shaped the current landscape.

- Discuss contemporary developments or current trends that provide relevant information to your research problem. This could include technological advancements, policy changes, or shifts in societal attitudes.

- Highlight the views of different stakeholders. For a topic like sustainable agriculture, this could mean discussing the perspectives of farmers, environmentalists, policymakers, and consumers.

- If relevant, compare and contrast global trends with local conditions and circumstances. This can offer readers a more holistic understanding of the topic.

Literature review

For this step, you’ll deep dive into the existing literature on the same topic. It's where you explore what scholars, researchers, and experts have already discovered or discussed about your topic.

Conducting a thorough literature review isn't just a recap of past works. To elevate its efficacy, it's essential to analyze the methods, outcomes, and intricacies of prior research work, demonstrating a thorough engagement with the existing body of knowledge.

- Instead of merely listing past research study, delve into their methodologies, findings, and limitations. Highlight groundbreaking studies and those that had contrasting results.

- Try to identify patterns. Look for recurring themes or trends in the literature. Are there common conclusions or contentious points?

- The next step would be to connect the dots. Show how different pieces of research relate to each other. This can help in understanding the evolution of thought on the topic.

By showcasing what's already known, you can better highlight the background of the study in research.

Highlight the research gap

This step involves identifying the unexplored areas or unanswered questions in the existing literature. Your research seeks to address these gaps, providing new insights or answers.

A clear research gap shows you've thoroughly engaged with existing literature and found an area that needs further exploration.

How can you efficiently highlight the research gap?

- Find the overlooked areas. Point out topics or angles that haven't been adequately addressed.

- Highlight questions that have emerged due to recent developments or changing circumstances.

- Identify areas where insights from other fields might be beneficial but haven't been explored yet.

State your objectives

Here, it’s all about laying out your game plan — What do you hope to achieve with your research? You need to mention a clear objective that’s specific, actionable, and directly tied to the research gap.

How to state your objectives?

- List the primary questions guiding your research.

- If applicable, state any hypotheses or predictions you aim to test.

- Specify what you hope to achieve, whether it's new insights, solutions, or methodologies.

Discuss the significance

This step describes your 'why'. Why is your research important? What broader implications does it have?

The significance of “why” should be both theoretical (adding to the existing literature) and practical (having real-world implications).

How do we effectively discuss the significance?

- Discuss how your research adds to the existing body of knowledge.

- Highlight how your findings could be applied in real-world scenarios, from policy changes to on-ground practices.

- Point out how your research could pave the way for further studies or open up new areas of exploration.

Summarize your points

A concise summary acts as a bridge, smoothly transitioning readers from the background to the main body of the paper. This step is a brief recap, ensuring that readers have grasped the foundational concepts.

How to summarize your study?

- Revisit the key points discussed, from the research problem to its significance.

- Prepare the reader for the subsequent sections, ensuring they understand the research's direction.

Include examples for better understanding

Research and come up with real-world or hypothetical examples to clarify complex concepts or to illustrate the practical applications of your research. Relevant examples make abstract ideas tangible, aiding comprehension.

How to include an effective example of the background of the study?

- Use past events or scenarios to explain concepts.

- Craft potential scenarios to demonstrate the implications of your findings.

- Use comparisons to simplify complex ideas, making them more relatable.

Crafting a compelling background of the study in research is about striking the right balance between providing essential context, showcasing your comprehensive understanding of the existing literature, and highlighting the unique value of your research .

While writing the background of the study, keep your readers at the forefront of your mind. Every piece of information, every example, and every objective should be geared toward helping them understand and appreciate your research.

How to avoid mistakes in the background of the study in research?

To write a well-crafted background of the study, you should be aware of the following potential research pitfalls .

- Stay away from ambiguity. Always assume that your reader might not be familiar with intricate details about your topic.

- Avoid discussing unrelated themes. Stick to what's directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure your background is well-organized. Information should flow logically, making it easy for readers to follow.

- While it's vital to provide context, avoid overwhelming the reader with excessive details that might not be directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure you've covered the most significant and relevant studies i` n your field. Overlooking key pieces of literature can make your background seem incomplete.

- Aim for a balanced presentation of facts, and avoid showing overt bias or presenting only one side of an argument.

- While academic paper often involves specialized terms, ensure they're adequately explained or use simpler alternatives when possible.

- Every claim or piece of information taken from existing literature should be appropriately cited. Failing to do so can lead to issues of plagiarism.

- Avoid making the background too lengthy. While thoroughness is appreciated, it should not come at the expense of losing the reader's interest. Maybe prefer to keep it to one-two paragraphs long.

- Especially in rapidly evolving fields, it's crucial to ensure that your literature review section is up-to-date and includes the latest research.

Example of an effective background of the study

Let's consider a topic: "The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance." The ideal background of the study section for this topic would be as follows.

In the last decade, the rise of the internet has revolutionized many sectors, including education. Online learning platforms, once a supplementary educational tool, have now become a primary mode of instruction for many institutions worldwide. With the recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rapid shift from traditional classroom learning to online modes, making it imperative to understand its effects on student performance.

Previous studies have explored various facets of online learning, from its accessibility to its flexibility. However, there is a growing need to assess its direct impact on student outcomes. While some educators advocate for its benefits, citing the convenience and vast resources available, others express concerns about potential drawbacks, such as reduced student engagement and the challenges of self-discipline.

This research aims to delve deeper into this debate, evaluating the true impact of online learning on student performance.

Why is this example considered as an effective background section of a research paper?

This background section example effectively sets the context by highlighting the rise of online learning and its increased relevance due to recent global events. It references prior research on the topic, indicating a foundation built on existing knowledge.

By presenting both the potential advantages and concerns of online learning, it establishes a balanced view, leading to the clear purpose of the study: to evaluate the true impact of online learning on student performance.

As we've explored, writing an effective background of the study in research requires clarity, precision, and a keen understanding of both the broader landscape and the specific details of your topic.

From identifying the research problem, providing context, reviewing existing literature to highlighting research gaps and stating objectives, each step is pivotal in shaping the narrative of your research. And while there are best practices to follow, it's equally crucial to be aware of the pitfalls to avoid.

Remember, writing or refining the background of your study is essential to engage your readers, familiarize them with the research context, and set the ground for the insights your research project will unveil.

Drawing from all the important details, insights and guidance shared, you're now in a strong position to craft a background of the study that not only informs but also engages and resonates with your readers.

Now that you've a clear understanding of what the background of the study aims to achieve, the natural progression is to delve into the next crucial component — write an effective introduction section of a research paper. Read here .

Frequently Asked Questions

The background of the study should include a clear context for the research, references to relevant previous studies, identification of knowledge gaps, justification for the current research, a concise overview of the research problem or question, and an indication of the study's significance or potential impact.

The background of the study is written to provide readers with a clear understanding of the context, significance, and rationale behind the research. It offers a snapshot of existing knowledge on the topic, highlights the relevance of the study, and sets the stage for the research questions and objectives. It ensures that readers can grasp the importance of the research and its place within the broader field of study.

The background of the study is a section in a research paper that provides context, circumstances, and history leading to the research problem or topic being explored. It presents existing knowledge on the topic and outlines the reasons that spurred the current research, helping readers understand the research's foundation and its significance in the broader academic landscape.

The number of paragraphs in the background of the study can vary based on the complexity of the topic and the depth of the context required. Typically, it might range from 3 to 5 paragraphs, but in more detailed or complex research papers, it could be longer. The key is to ensure that all relevant information is presented clearly and concisely, without unnecessary repetition.

You might also like

Smallpdf vs SciSpace: Which ChatPDF is Right for You?

ChatPDF Showdown: SciSpace Chat PDF vs. Adobe PDF Reader

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

Background of the Study

Ai generator.

The background of the study provides a comprehensive overview of the research problem, including the context , significance, and gaps in existing knowledge. It sets the stage for the research by outlining the historical, theoretical, and practical aspects that have led to the current investigation, highlighting the importance of addressing the identified issues.

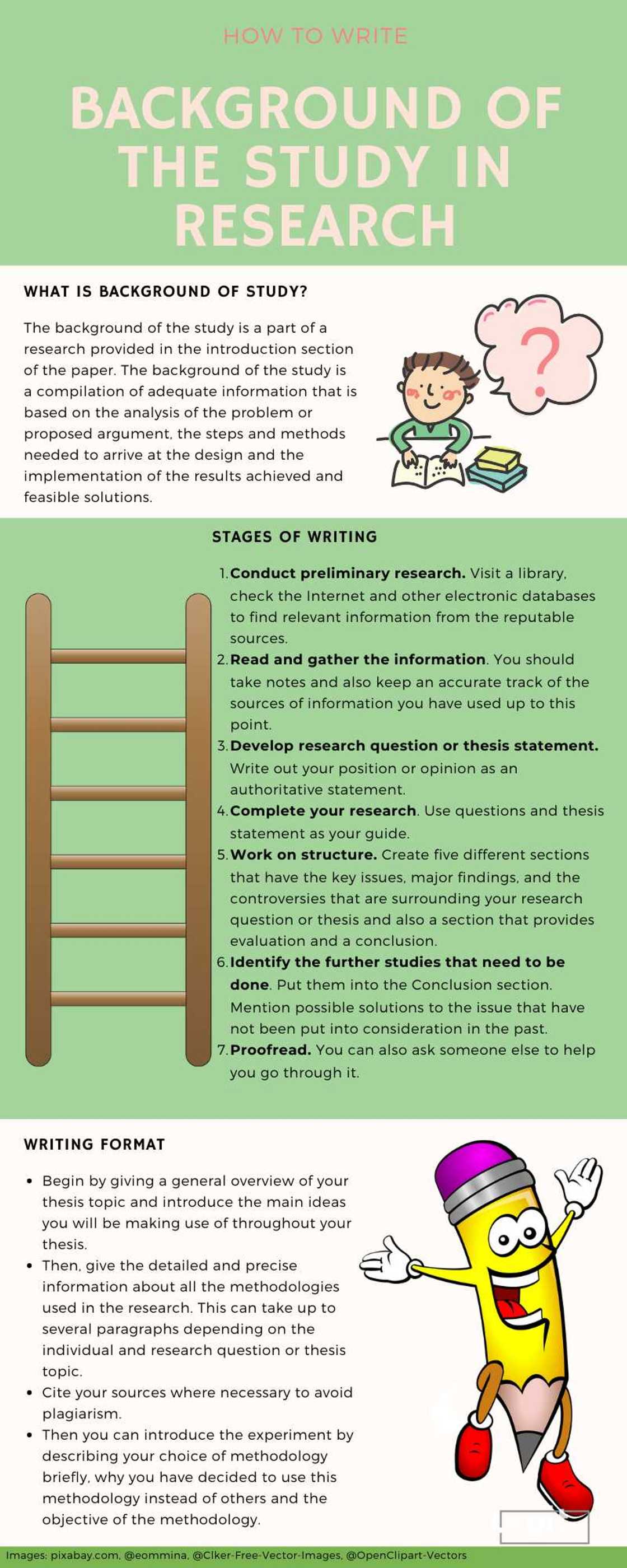

What is the Background of a Study?

The background of a study provides context by explaining the research problem, highlighting gaps in existing knowledge, and establishing the study’s significance. It sets the stage for the research objective , offering a foundation for understanding the study’s purpose and relevance within the broader academic discourse.

Background of the Study Format

The background of the study is a foundational section in any research paper or thesis . Here is a structured format to follow:

1. Introduction

- Briefly introduce the topic and its relevance.

- Mention the research problem or question.

2. Contextual Framework

- Provide historical background.

- Discuss relevant theories and models.

- Explain the practical context.

3. Literature Review

- Summarize key studies related to the topic.

- Highlight significant findings and their implications.

- Identify gaps in the existing literature.

4. Rationale

- Explain why the study is necessary.

- Discuss the significance and potential impact.

- Justify the research focus and scope.

5. Objectives and Research Questions

- State the primary objective of the study.

- List the specific research questions.

6. Conclusion

- Summarize the importance of the background.

- Emphasize how it sets the stage for the research.

Introduction The increasing incidence of climate change and its effects on global agriculture has raised significant concerns among researchers. This study focuses on the impact of climate change on crop yields. Contextual Framework Historically, agricultural practices have adapted to gradual climate changes. However, recent rapid shifts have outpaced these adaptations, necessitating urgent research. Theoretical models of climate adaptation provide a foundation for understanding these changes. Literature Review Recent studies show mixed results on the extent of climate change impacts on agriculture. While some regions experience reduced yields, others report minimal changes. These discrepancies highlight the need for a focused study on regional impacts. Rationale This research is crucial for developing strategies to mitigate adverse effects on agriculture. Understanding specific regional impacts can help tailor interventions, making this study highly significant for policymakers and farmers. Objectives and Research Questions To assess the impact of climate change on crop yields in the Midwest. What are the main climate factors affecting agriculture in this region? How can farmers adapt to these changes effectively? Conclusion The background of the study underscores its relevance and importance, providing a solid foundation for the research. By addressing identified gaps, this study aims to contribute valuable insights into climate change adaptation strategies in agriculture.

Background of the Study Examples

Impact of social media on academic performance, effects of urbanization on local ecosystems, role of nutrition in early childhood development.

More Background of the Study Examples

- Online Learning and Reading Skills

- Mindfulness at Work

- Parental Role in Preventing Childhood Obesity

- Green Building and Energy Efficiency

- Peer Tutoring in High Schools

- Remote Work and Work-Life Balance

- Technology in Healthcare

Background of the Study in Research Example

Background of the Study in Qualitative Research Example

Importance of Background of the Study

The background of the study is essential for several reasons:

- Context Establishment : It sets the stage for the research by outlining the historical, theoretical, and practical contexts.

- Literature Review : It provides a summary of existing literature, highlighting what is already known and identifying gaps in knowledge.

- Research Justification : It explains why the study is necessary, showcasing its relevance and significance.

- Research Direction : It guides the research questions and objectives, ensuring the study is focused and coherent.

- Foundation for Methodology : It lays the groundwork for the research methodology, explaining the choice of methods and approaches.

- Informing Stakeholders : It helps stakeholders understand the importance and potential impact of the research.

How is the Background of a Study Different From the Introduction?

The background of a study and the introduction serve distinct but complementary purposes in a research paper. Here’s how they differ:

- Provides detailed context for the research problem.

- Explains the historical, theoretical, and practical background of the topic.

- Identifies gaps in existing knowledge that the study aims to fill.

- Includes a comprehensive literature review.

- Discusses relevant theories, models, and previous research findings.

- Sets the stage for the study by explaining why it is important and necessary.

- Typically more detailed and longer than the introduction.

- Provides in-depth information to help readers understand the broader context of the research.

Introduction

- Introduces the topic and the research problem in a concise manner.

- Captures the reader’s interest and sets the stage for the rest of the paper.

- States the research objectives, questions, and sometimes hypotheses.

- Brief overview of the topic and its significance.

- Clear statement of the research problem.

- Outline of the study’s objectives and research questions.

- May include a brief mention of the methodology and scope.

- Typically shorter and more succinct than the background.

- Provides a snapshot of what the study is about without going into detailed literature review or theoretical background.

Example to Illustrate the Difference

Introduction Example : The rapid growth of social media usage among students has raised concerns about its impact on academic performance. This study aims to investigate how social media influences students’ grades and study habits. By examining different platforms and usage patterns, the research seeks to provide insights into whether social media acts as a distraction or a beneficial tool for learning. Background of the Study Example : Social media has transformed communication and information sharing, particularly among young people. Historically, educational environments have seen various technological impacts, from the introduction of computers to the widespread use of the internet. Theories of digital learning suggest both positive and negative effects of technology on education. Previous studies have shown mixed results; some indicate that social media can enhance collaborative learning and resource access, while others point to decreased academic performance due to distraction. Despite these findings, there is limited research on the long-term effects of specific social media platforms on academic outcomes. This study addresses these gaps by exploring how different types of social media usage impact student performance, aiming to provide a nuanced understanding of this contemporary issue.

Where is the Background of a Study Placed in a Research Paper?

The background of a study is typically placed within the Introduction section of a research paper, but it can also be a separate section immediately following the introduction. Here’s a more detailed breakdown of where the background of the study can be placed:

Within the Introduction

- In many research papers, the background of the study is woven into the introduction. It provides context and justification for the research problem, leading up to the statement of the research objectives and questions.

- Starts with a general introduction to the topic.

- Provides background information and context.

- Reviews relevant literature and identifies gaps.

- States the research problem, objectives, and questions.

As a Separate Section

- In more detailed or longer research papers, the background of the study can be a standalone section that comes immediately after the introduction. This allows for a more comprehensive presentation of the context, literature review, and theoretical framework.

- Introduction : Briefly introduces the topic and states the research problem.

- Background of the Study : Provides detailed context, literature review, theoretical background, and justification for the research.

- Research Objectives and Questions : Clearly states the aims and specific questions the research seeks to answer.

How to Write a Background of the Study

Writing a background of the study involves providing a comprehensive overview of the research problem, context, and significance. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an effective background of the study:

Introduce the Topic

Begin with a General Introduction : Start by introducing the broad topic to give readers an overview of the field. Example : “Social media has revolutionized communication and information sharing in the digital age.”

Provide Context

Historical Background : Explain the historical development of the topic. Example : “Historically, communication technologies have significantly influenced educational practices, from the introduction of the internet to the advent of mobile learning.” Theoretical Framework : Mention relevant theories and models. Example : “Theories such as social constructivism and digital learning provide a basis for understanding how students interact and learn through social media.”

Review Relevant Literature

Summarize Key Studies : Provide a summary of significant studies related to your topic. Example : “Previous research has shown mixed results regarding the impact of social media on academic performance. Some studies suggest that social media can be a distraction, leading to lower grades, while others indicate it can enhance learning through collaboration.” Identify Gaps in Knowledge : Highlight gaps or inconsistencies in the existing literature. Example : “Despite extensive research, there is limited understanding of the long-term effects of specific social media platforms on student performance.”

Explain the Rationale

Justify the Need for the Study : Explain why your study is necessary and important. Example : “Assessing the impact of social media on academic performance is crucial for developing effective educational strategies and policies. This study aims to fill the existing knowledge gaps by providing detailed insights into how different platforms affect student learning outcomes.”

State the Research Objectives and Questions

List the Objectives : Clearly state the main objectives of your study. Example : “The primary objectives of this study are to analyze the relationship between social media usage and academic performance and to identify the most and least beneficial platforms for students.” Pose Research Questions : Include specific research questions that guide your study. Example : “What are the main factors influencing the impact of social media on academic performance? How can students balance social media use and academic responsibilities?”

Conclude with the Importance of the Study

Summarize the Significance : Emphasize how your study will contribute to the field. Example : “This study’s findings will provide valuable insights into the role of social media in education, informing educators and policymakers on how to leverage these tools effectively to enhance student learning outcomes.”

How to avoid mistakes in writing the Background of a Study

Avoiding mistakes in writing the background of a study involves careful planning, thorough research, and attention to detail. Here are some tips to help you avoid common mistakes:

1. Lack of Clarity and Focus

- Example : If your research is about the impact of social media on student performance, don’t delve into unrelated topics like general internet usage unless directly relevant.

2. Insufficient Literature Review

- Example : Use databases like Google Scholar, PubMed, or your institution’s library to find peer-reviewed articles and credible sources.

3. Overwhelming with Too Much Information

- Example : Summarize key studies and avoid detailed descriptions of every study you come across.

4. Failure to Identify Gaps in Knowledge

- Example : “While several studies have explored social media’s impact on general communication skills, few have examined its specific effects on academic performance among high school students.”

5. Lack of Theoretical Framework

- Example : “The study is grounded in social constructivism, which suggests that learning occurs through social interactions, making it relevant to examine how social media platforms facilitate these interactions.”

6. Inadequate Justification for the Study

- Example : “Understanding the impact of social media on academic performance is crucial for developing effective educational strategies and policies.”

7. Poor Organization and Structure

- Example : Use clear headings like “Introduction,” “Contextual Framework,” “Literature Review,” “Rationale,” and “Research Objectives and Questions.”

8. Using Jargon and Complex Language

- Example : Instead of “The pedagogical implications of digital media necessitate a paradigmatic shift,” say “Digital media impacts teaching methods, requiring changes in how we educate.”

9. Ignoring the Research Objectives and Questions

- Example : “This background review highlights the need to investigate how different social media platforms affect high school students’ study habits, directly addressing the research questions outlined.”

10. Neglecting to Update References

- Example : Instead of relying solely on sources from over a decade ago, incorporate recent studies that reflect current trends and findings.

What is the background of the study?

The background of the study provides context, explains the research problem, reviews relevant literature, and identifies gaps the study aims to fill.

Why is the background of the study important?

It establishes the context and significance of the research, justifies the study, and helps readers understand the broader academic landscape and gaps the research addresses.

How does the background of the study differ from the introduction?

The background provides detailed context and literature review, while the introduction briefly presents the research problem, objectives, and significance.

What should be included in the background of the study?

Include historical context, theoretical framework, literature review, gaps in knowledge, and the rationale for the study.

Where is the background of the study placed in a research paper?

It is typically integrated within the introduction or presented as a separate section following the introduction.

How long should the background of the study be?

The length varies, but it should be detailed enough to provide context and justification, typically a few paragraphs to several pages.

How do you write a strong background of the study?

Conduct thorough research, organize logically, include relevant theories and studies, identify gaps, and justify the research’s importance.

Can the background of the study include preliminary data?

Yes, including preliminary data can strengthen the background by demonstrating initial findings and supporting the research rationale.

How do you identify gaps in the literature?

Conduct a comprehensive literature review, compare findings, and note inconsistencies, unexplored areas, or outdated research that your study will address.

Should the background of the study be written in chronological order?

Not necessarily. Organize logically by themes, concepts, or research gaps rather than strictly chronologically to provide a coherent context for your study.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

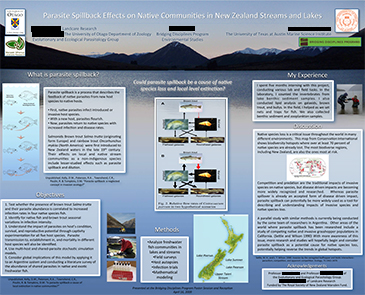

PROCEDURE FOR WRITING A BACKGROUND STUDY FOR A RESEARCH PAPER - WITH A PRACTICAL EXAMPLE BY DR BENARD LANGO

2020, DR BENARD LANGO RESEARCH SCHOOL

Many research documents when reviewed wholesomely in most instances fails the background study test as the authors either presume it is a section notes on the research or just a section to ensure is fully written with materials related to the research area. It is important to note that research background study will define the relevance of the study topic and whether its intention to contribute to the area of knowledge is relevant. In order to be able to write background study the study area commonly described by the study topic will be of at most importance. From the topic one should be able to derive the both the independent and dependent variables to be able to follow this structure of writing a background for the study.

Related Papers

Journal of Universal College of Medical Sciences

bishal joshi

INTRODUCTION A research paper is a part of academic writing where there is a gathering of information from different sources. It is multistep process. Selection of title is the most important part of research writing. The title which is interesting should be chosen for the research purpose. All the related information is gathered and the title for research is synthesized. After thorough understanding and developing the title, the preliminary outline is made which maintains the logical path for its exploration. After preliminary research, proper research work is started with collection of previous resources which is then organized and important points are noted. Then research paper is written by referring to outlines, notes, articles, journals and books. The research paper should be well structured containing core parts like introduction, material and methods, results and disscussion and important additional parts like title, abstract, references.

Sher Singh Bhakar

Organisation of Book: The book is organized into two parts. Part one starts with thinking critically about research, explains what is (and isn’t) research, explains how to properly use research in your writing to make your points, introduces a series of writing exercises designed to help students to think about and write effective research papers. Instead of explaining how to write a single “research paper,” The Process of Research Writing part of the book breaks down the research process into many smaller and easier-to manage parts like what is a research paper, starting steps for writing research papers, writing conceptual understanding and review of literature, referencing including various styles of referencing, writing research methodology and results including interpretations, writing implications and limitations of research and what goes into conclusions. Part two contains sample research articles to demonstrate the application of techniques and methods of writing good resear...

Kevin O'Donnell

Maluk Them John

Jeff Immanuel

Ana Stefanelli

Scientific Research Journal of Clinical and Medical Sciences

Ahmed Alkhaqani

Background: Confusion about elements of a research paper is common among students. The key to writing a good research paper is to know these common elements and their definitions. Maybe find that writing a research paper is not as easy as it seems. There are many parts and steps to the process, and it can be hard to figure out what needs to do and when. Objective: This article aims to teach these common aspects of a research paper to avoid common mistakes while drafting own. Conclusion: Each section of the research paper serves a distinct purpose and highlights a different aspect of the research. However, before starting drafting the manuscript, having a clear understanding of each section's purposes will help avoid mistakes.

IAA Journal of Applied Sciences

EZE V A L H Y G I N U S UDOKA

Many young researchers find it difficult to write a good and quality research thesis/article because they are not prone to article writing ethics and training. Yet, a thesis/publication is often vital and paramount for career advancement, grants, academic qualifications and others. This research work described the basics and systematic steps to follow in writing a good scientific thesis/article. This research also outlined the main sections that an average thesis/article should contain, the elements that should appear in each section, the systematic approaches in writing research, the characteristics of a good thesis/article, the attributes of a good research thesis/article, qualities of a good researcher and finally the ethics guiding research.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Langley, BC: Trinity Western University. …

Paul T P Wong

Stevejobs.education

Dr. David Annan

Muhammad Obaidullah

Hossein Saiedian

Putri Ramadhani

abasynuniv.edu.pk

Flora Maleki

Renaldi Bimantoro

British journal of community nursing

Keith Meadows

Holuphumiee Adegbaju

Maamar Missoum

christopher Boateng

Faith Gatune

nikhil arora

Alex Galarosa

Akhil Rashinkar

Lawrence Rudner

IJAR Indexing

UncleChew Bah

almina ocampo

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

PHILO-notes

Free Online Learning Materials

How to Write the Background of the Study in Research (Part 1)

Background of the Study in Research: Definition and the Core Elements it Contains

Before we embark on a detailed discussion on how to write the background of the study of your proposed research or thesis, it is important to first discuss its meaning and the core elements that it should contain. This is obviously because understanding the nature of the background of the study in research and knowing exactly what to include in it allow us to have both greater control and clear direction of the writing process.

So, what really is the background of the study and what are the core elements that it should contain?

The background of the study, which usually forms the first section of the introduction to a research paper or thesis, provides the overview of the study. In other words, it is that section of the research paper or thesis that establishes the context of the study. Its main function is to explain why the proposed research is important and essential to understanding the main aspects of the study.

The background of the study, therefore, is the section of the research paper or thesis that identifies the problem or gap of the study that needs to addressed and justifies the need for conducting the study. It also articulates the main goal of the study and the thesis statement, that is, the main claim or argument of the paper.

Given this brief understanding of the background of the study, we can anticipate what readers or thesis committee members expect from it. As we can see, the background of the study should contain the following major points:

1) brief discussion on what is known about the topic under investigation; 2) An articulation of the research gap or problem that needs to be addressed; 3) What the researcher would like to do or aim to achieve in the study ( research goal); 4) The thesis statement, that is, the main argument or contention of the paper (which also serves as the reason why the researcher would want to pursue the study); 5) The major significance or contribution of the study to a particular discipline; and 6) Depending on the nature of the study, an articulation of the hypothesis of the study.

Thus, when writing the background of the study, you should plan and structure it based on the major points just mentioned. With this, you will have a clear picture of the flow of the tasks that need to be completed in writing this section of your research or thesis proposal.

Now, how do you go about writing the background of the study in your proposed research or thesis?

The next lessons will address this question.

How to Write the Opening Paragraphs of the Background of the Study?

To begin with, let us assume that you already have conducted a preliminary research on your chosen topic, that is, you already have read a lot of literature and gathered relevant information for writing the background of your study. Let us also assume that you already have identified the gap of your proposed research and have already developed the research questions and thesis statement. If you have not yet identified the gap in your proposed research, you might as well go back to our lesson on how to identify a research gap.

So, we will just put together everything that you have researched into a background of the study (assuming, again, that you already have the necessary information). But in this lesson, let’s just focus on writing the opening paragraphs.

It is important to note at this point that there are different styles of writing the background of the study. Hence, what I will be sharing with you here is not just “the” only way of writing the background of the study. As a matter of fact, there is no “one-size-fits-all” style of writing this part of the research or thesis. At the end of the day, you are free to develop your own. However, whatever style it would be, it always starts with a plan which structures the writing process into stages or steps. The steps that I will share with below are just some of the most effective ways of writing the background of the study in research.

So, let’s begin.

It is always a good idea to begin the background of your study by giving an overview of your research topic. This may include providing a definition of the key concepts of your research or highlighting the main developments of the research topic.

Let us suppose that the topic of your study is the “lived experiences of students with mathematical anxiety”.

Here, you may start the background of your study with a discussion on the meaning, nature, and dynamics of the term “mathematical anxiety”. The reason for this is too obvious: “mathematical anxiety” is a highly technical term that is specific to mathematics. Hence, this term is not readily understandable to non-specialists in this field.

So, you may write the opening paragraph of your background of the study with this:

“Mathematical anxiety refers to the individual’s unpleasant emotional mood responses when confronted with a mathematical situation.”

Since you do not invent the definition of the term “mathematical anxiety”, then you need to provide a citation to the source of the material from which you are quoting. For example, you may now say:

“Mathematical anxiety refers to the individual’s unpleasant emotional mood responses when confronted with a mathematical situation (Eliot, 2020).”

And then you may proceed with the discussion on the nature and dynamics of the term “mathematical anxiety”. You may say:

“Lou (2019) specifically identifies some of the manifestations of this type of anxiety, which include, but not limited to, depression, helplessness, nervousness and fearfulness in doing mathematical and numerical tasks.”

After explaining to your readers the meaning, nature, and dynamics (as well as some historical development if you wish to) of the term “mathematical anxiety”, you may now proceed to showing the problem or gap of the study. As you may already know, the research gap is the problem that needs to be addressed in the study. This is important because no research activity is possible without the research gap.

Let us suppose that your research problem or gap is: “Mathematical anxiety can negatively affect not just the academic achievement of the students but also their future career plans and total well-being. Also, there are no known studies that deal with the mathematical anxiety of junior high school students in New Zealand.” With this, you may say:

“If left unchecked, as Shapiro (2019) claims, this problem will expand and create a total avoidance pattern on the part of the students, which can be expressed most visibly in the form of cutting classes and habitual absenteeism. As we can see, this will negatively affect the performance of students in mathematics. In fact, the study conducted by Luttenberger and Wimmer (2018) revealed that the outcomes of mathematical anxiety do not only negatively affect the students’ performance in math-related situations but also their future career as professionals. Without a doubt, therefore, mathematical anxiety is a recurring problem for many individuals which will negatively affect the academic success and future career of the student.”

Now that you already have both explained the meaning, nature, and dynamics of the term “mathematical anxiety” and articulated the gap of your proposed research, you may now state the main goal of your study. You may say:

“Hence, it is precisely in this context that the researcher aims to determine the lived experiences of those students with mathematical anxiety. In particular, this proposed thesis aims to determine the lived experiences of the junior high school students in New Zealand and identify the factors that caused them to become disinterested in mathematics.”

Please note that you should not end the first paragraph of your background of the study with the articulation of the research goal. You also need to articulate the “thesis statement”, which usually comes after the research goal. As is well known, the thesis statement is the statement of your argument or contention in the study. It is more of a personal argument or claim of the researcher, which specifically highlights the possible contribution of the study. For example, you may say:

“The researcher argues that there is a need to determine the lived experiences of these students with mathematical anxiety because knowing and understanding the difficulties and challenges that they have encountered will put the researcher in the best position to offer some alternatives to the problem. Indeed, it is only when we have performed some kind of a ‘diagnosis’ that we can offer practicable solutions to the problem. And in the case of the junior high school students in New Zealand who are having mathematical anxiety, determining their lived experiences as well as identifying the factors that caused them to become disinterested in mathematics are the very first steps in addressing the problem.”

If we combine the bits and pieces that we have written above, we can now come up with the opening paragraphs of your background of the study, which reads:

As we can see, we can find in the first paragraph 5 essential elements that must be articulated in the background of the study, namely:

1) A brief discussion on what is known about the topic under investigation; 2) An articulation of the research gap or problem that needs to be addressed; 3) What the researcher would like to do or aim to achieve in the study (research goal); 4) The thesis statement , that is, the main argument or claim of the paper; and 5) The major significance or contribution of the study to a particular discipline. So, that’s how you write the opening paragraphs of your background of the study. The next lesson will talk about writing the body of the background of the study.

How to Write the Body of the Background of the Study?

If we liken the background of the study to a sitting cat, then the opening paragraphs that we have completed in the previous lesson would just represent the head of the cat.

This means we still have to write the body (body of the cat) and the conclusion (tail). But how do we write the body of the background of the study? What should be its content?

Truly, this is one of the most difficult challenges that fledgling scholars faced. Because they are inexperienced researchers and didn’t know what to do next, they just wrote whatever they wished to write. Fortunately, this is relatively easy if they know the technique.

One of the best ways to write the body of the background of the study is to attack it from the vantage point of the research gap. If you recall, when we articulated the research gap in the opening paragraphs, we made a bold claim there, that is, there are junior high school students in New Zealand who are experiencing mathematical anxiety. Now, you have to remember that a “statement” remains an assumption until you can provide concrete proofs to it. This is what we call the “epistemological” aspect of research. As we may already know, epistemology is a specific branch of philosophy that deals with the validity of knowledge. And to validate knowledge is to provide concrete proofs to our statements. Hence, the reason why we need to provide proofs to our claim that there are indeed junior high school students in New Zealand who are experiencing mathematical anxiety is the obvious fact that if there are none, then we cannot proceed with our study. We have no one to interview with in the first. In short, we don’t have respondents.

The body of the background of the study, therefore, should be a presentation and articulation of the proofs to our claim that indeed there are junior high school students in New Zealand who are experiencing mathematical anxiety. Please note, however, that this idea is true only if you follow the style of writing the background of the study that I introduced in this course.

So, how do we do this?

One of the best ways to do this is to look for literature on mathematical anxiety among junior high school students in New Zealand and cite them here. However, if there are not enough literature on this topic in New Zealand, then we need to conduct initial interviews with these students or make actual classroom observations and record instances of mathematical anxiety among these students. But it is always a good idea if we combine literature review with interviews and actual observations.

Assuming you already have the data, then you may now proceed with the writing of the body of your background of the study. For example, you may say:

“According to records and based on the researcher’s firsthand experience with students in some junior high schools in New Zealand, indeed, there are students who lost interest in mathematics. For one, while checking the daily attendance and monitoring of the students, it was observed that some of them are not always attending classes in mathematics but are regularly attending the rest of the required subjects.”

After this sentence, you may insert some literature that will support this position. For example, you may say:

“As a matter of fact, this phenomenon is also observed in the work of Estonanto. In his study titled ‘Impact of Math Anxiety on Academic Performance in Pre-Calculus of Senior High School’, Estonanto (2019) found out that, inter alia, students with mathematical anxiety have the tendency to intentionally prioritize other subjects and commit habitual tardiness and absences.”

Then you may proceed saying:

“With this initial knowledge in mind, the researcher conducted initial interviews with some of these students. The researcher learned that one student did not regularly attend his math subject because he believed that he is not good in math and no matter how he listens to the topic he will not learn.”

Then you may say:

“Another student also mentioned that she was influenced by her friends’ perception that mathematics is hard; hence, she avoids the subject. Indeed, these are concrete proofs that there are some junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety. As already hinted, “disinterest” or the loss of interest in mathematics is one of the manifestations of a mathematical anxiety.”

If we combine what we have just written above, then we can have the first two paragraphs of the body of our background of the study. It reads:

“According to records and based on the researcher’s firsthand experience with students in some junior high schools in New Zealand, indeed there are students who lost interest in mathematics. For one, while checking the daily attendance and monitoring of the students, it was observed that some of them are not always attending classes in mathematics but are regularly attending the rest of the required subjects. As a matter of fact, this phenomenon is also observed in the work of Estonanto. In his study titled ‘Impact of Math Anxiety on Academic Performance in Pre-Calculus of Senior High School’, Estonanto (2019) found out that, inter alia, students with mathematical anxiety have the tendency to intentionally prioritize other subjects and commit habitual tardiness and absences.

With this initial knowledge in mind, the researcher conducted initial interviews with some of these students. The researcher learned that one student did not regularly attend his math subject because he believed that he is not good in math and no matter how he listens to the topic he will not learn. Another student also mentioned that she was influenced by her friends’ perception that mathematics is hard; hence, she avoids the subject. Indeed, these are concrete proofs that there are some junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety. As already hinted, “disinterest” or the loss of interest in mathematics is one of the manifestations of a mathematical anxiety.”

And then you need validate this observation by conducting another round of interview and observation in other schools. So, you may continue writing the body of the background of the study with this:

“To validate the information gathered from the initial interviews and observations, the researcher conducted another round of interview and observation with other junior high school students in New Zealand.”

“On the one hand, the researcher found out that during mathematics time some students felt uneasy; in fact, they showed a feeling of being tensed or anxious while working with numbers and mathematical problems. Some were even afraid to seat in front, while some students at the back were secretly playing with their mobile phones. These students also show remarkable apprehension during board works like trembling hands, nervous laughter, and the like.”

Then provide some literature that will support your position. You may say:

“As Finlayson (2017) corroborates, emotional symptoms of mathematical anxiety involve feeling of helplessness, lack of confidence, and being nervous for being put on the spot. It must be noted that these occasionally extreme emotional reactions are not triggered by provocative procedures. As a matter of fact, there are no personally sensitive questions or intentional manipulations of stress. The teacher simply asked a very simple question, like identifying the parts of a circle. Certainly, this observation also conforms with the study of Ashcraft (2016) when he mentions that students with mathematical anxiety show a negative attitude towards math and hold self-perceptions about their mathematical abilities.”

And then you proceed:

“On the other hand, when the class had their other subjects, the students show a feeling of excitement. They even hurried to seat in front and attentively participating in the class discussion without hesitation and without the feeling of being tensed or anxious. For sure, this is another concrete proof that there are junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety.”

To further prove the point that there indeed junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety, you may solicit observations from other math teachers. For instance, you may say:

“The researcher further verified if the problem is also happening in other sections and whether other mathematics teachers experienced the same observation that the researcher had. This validation or verification is important in establishing credibility of the claim (Buchbinder, 2016) and ensuring reliability and validity of the assertion (Morse et al., 2002). In this regard, the researcher attempted to open up the issue of math anxiety during the Departmentalized Learning Action Cell (LAC), a group discussion of educators per quarter, with the objective of ‘Teaching Strategies to Develop Critical Thinking of the Students’. During the session, one teacher corroborates the researcher’s observation that there are indeed junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety. The teacher pointed out that truly there were students who showed no extra effort in mathematics class in addition to the fact that some students really avoided the subject. In addition, another math teacher expressed her frustrations about these students who have mathematical anxiety. She quipped: “How can a teacher develop the critical thinking skills or ability of the students if in the first place these students show avoidance and disinterest in the subject?’.”

Again, if we combine what we have just written above, then we can now have the remaining parts of the body of the background of the study. It reads:

So, that’s how we write the body of the background of the study in research . Of course, you may add any relevant points which you think might amplify your content. What is important at this point is that you now have a clear idea of how to write the body of the background of the study.

How to Write the Concluding Part of the Background of the Study?

Since we have already completed the body of our background of the study in the previous lesson, we may now write the concluding paragraph (the tail of the cat). This is important because one of the rules of thumb in writing is that we always put a close to what we have started.