- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

A Brief History of Queer Language Before Queer Identity

"shade comes from reading. reading came first." –dorian corey.

Throughout literary history, queers have had to be smarter than the rest: we’ve had to hide in plain sight.

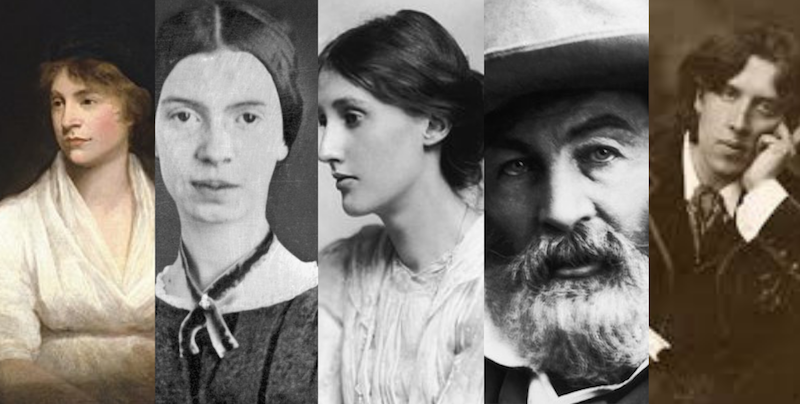

In a literary canon full of straight, white men, it can be a powerful thing to suggest that some of our most beloved writers may have been queer—and a more powerful thing, still, to have those suggestions be validated by primary texts, to have writers like Walt Whitman and Virginia Woolf definitively shown to have had same-sex relationships. In a time when right-wing nationalism is sweeping the globe, the stakes can feel so high when reclaiming long-dead writers as queer, as trans; when saying, we have always been here .

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots. Simultaneously, the Supreme Court has allowed a ban on the service of openly trans military members to go into effect. Reports of transgender people having their passports’ gender markers retroactively revoked are increasing. Devastating immigration policies continue to put LGBTQ+ migrants to the United States at severe risk. Sexual orientation and gender identity continue to be unprotected classes in many states, with a lack of legal recognition for gender expansiveness on nearly every level.

The official history of these institutions is not, and has never been, a history of people who exist on the margins. If you believe your history textbook tells the whole story—if you believe a history of the state—then your history of queer folks is going to be markedly short, especially if you are looking for queer and trans people of color.

We find at least some kind of history of queer folks if we look to art, to literature, to the text and the subtext. There, you find that we are here and have been here and will always be here, motherfucker. But we , inasmuch as there can be a collective “we” across the vast expanse of queer experience, haven’t always used the same language, the same mechanisms of activism and community, the same methodologies of being in the world or even conceiving of the self. Hell, the idea of a self as queer writers today think of it is so definitively post-Enlightenment that to read queer-ish texts from before the year 1700 can feel like a fool’s errand.

It is important, then, for modern queer activists and audiences and people to establish our history, because history is where we find validation, both for its own sake ( not alone not alone not alone ), but also as defense: it’s a validation against the accusation of us as sin, as aberrant. Queers are one of those few groups on the margins who are—not always, but often—raised in natal families where we are alone in our experience. Alone, to navigate the terrain. Alone, to find our history.

I am first in line when it comes to wanting to claim the dead as One of us! One of us! I left a PhD program after four years but still write about queer literary foremothers like Virginia Woolf and Mary Oliver. I’m never not reading (or viewing) media with a queer lens. But that lens is also informed by the fact that my academic work was grounded in the long 18th century, between 1680 and 1820, when print exploded (due to the printing press) and, consequently, mass media representations of sexuality rose to the fore. The ways we talk about sex and sexuality—let alone sexuality as an identity category—are constantly changing. The definition of queer and queer sexuality has changed dramatically over the last several hundred years; in many ways, it is anachronistic to refer to queer writers as an identity category, for the simple fact that it sexuality was, in many ways, not an identity category even a hundred years ago in the ways it has become an identity category, now, and this impacts how we interact with queer-coded texts from before.

Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer opens with one of the most famous and influential American writers in history: Walt Whitman. I remember reading Whitman as an undergrad. I didn’t get his poetry; I found it boring. I certainly never learned that Whitman was gay, that he hid in plain sight by, really, not hiding at all. Whitman was public about his sexuality, as much as he could be, because he could be: he was white and cis and masculine-presenting, and, like Ryan notes in his book, he had the freedom to move about the world with a rare security and forwardness. He slept with men on the docks and with fellow celebrity writers; Oscar Wilde, for one (who he called my big strapping boy ). Consequently, Whitman is the rare writer who has left behind a treasure trove of personal papers (like Wilde) that confirms so much and makes it relatively simple to interpret the queerness of his work.

Ryan’s research breaks open an abundance of language that was used as queers ebbed and flowed throughout queer history. Ryan talks about fairies and inverts and faggots and degenerates, about how words used to describe women or lower-class folks (like “floozy”) were absorbed as gay slurs.

When Brooklyn Was Queer is breathtaking in its scope, in the depth of what Ryan uncovers with limited primary documents—and it affirms that the definitions of sexuality, identity, orientation, and even what we would call queer community are anything but concrete. The beauty of queer experience is in its ability to shift and mutate and absorb and redefine itself, adapting within and against a culture that constantly seeks to root it out.

In History of Sexuality , Foucault famously wrote that sexuality had replaced the soul as the question in which society had become most interested: no longer were we primarily concerned with the state of a person’s eternal wellbeing, but instead with whom and how they preferred to spend their evening hours. (In this, we find something of an answer to why the Church has pursued and hunted and restricted sexuality to the far corners of the earth: it is, simply put, its competition.) This replacing of the soul with sexuality is a 20th century shift, a modern question.

Language is plastic, and the organization of sexuality—of specific actions and orientations—into labeled buckets, as it were, comes to us post-Enlightenment. Prior to the Enlightenment, the emphasis was on labeling people according to their actions, or sins. Sodomite , for example: a man who engaged in sex with another man. Lesbian and tribad and invert and sapphist were all still being used relatively interchangeably at the turn of the twentieth century; in some literature, lesbian was the female equivalent of sodomite , itself a negatively charged legal term.

The word homosexual comes to us around 1869 from Germany, and is often credited by Michel Foucault to Karl Westphal’s paper “Contrary Sexual Feeling.” Westphal, also the person who coined the phrase agoraphobia, among others, categorized the homosexual as a sexually disordered person.

Categories for LGBTQ+ people were principally used as medical categories (to label what was wrong with them) and legal categories (to punish them for their “wrongness”). When a modern audience scoffs at Modernist writer Djuna Barnes—who lived a notoriously open queer life in Greenwich Village in the 1920s—saying “I’m not a lesbian, I just love Thelma,” there is a failure to take into account the world in which she lived.

There is also the category of romantic friendship, particularly called such among women; queer theorist Eve Sedgwick might call it homosociality . This category is so foreign to modern readers that there is difficulty intellectually understanding it: the rigid way of associating and preferring the company of one’s own gender, with physical affection and deep intimacy and love, but without eroticism. How can there be no hint of eroticism? How can homophobia be a foundation of this, particularly among men?

Queer recovery and queer theory—like feminist theory and feminist recovery—applied to historical texts have been vital to finding and unearthing writers whose work has been lost or hidden. But when it comes to queerness, we have to be mindful of language as shifting tectonic plates beneath our feet. Language was a code; language was a shield. We’ve taken advantage of same-sex categories and codes that, in more regimented and traditional societies, were more prevalent—chivalrous codes, romantic friendship that encouraged love letters among women to pass completely normally.

Take the infamous late 18th century feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, whose intimate friendship with Fanny Blood is often considered an inspiration for the deeply homoerotic relationship between the characters Mary and Ann in Wollstonecraft’s oft-forgotten first novella, Mary: A Fiction . A potentially positive queer reading of Wollstonecraft’s biography is complicated by her critical statements about sodomy in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, in part because of a modern insistence on psychic cohesion: the surprise, by modern readers, that such explicit homophobia could exist within work by the same author who also wrote such a queer-friendly text. Scholars have disputed whether Wollstonecraft’s statements in Vindication are, in fact, “homophobic,” considering the very concept of homophobia too modern, too reliant on coherent definitions of sexual identity to be definitively applied.

In our modern era where sexuality is, for many, a distinct psychosexual identity, we run the risk of anachronistic projections on writers and artists from past centuries whose conception of sexuality was different. We can do queer readings of the texts of Emily Dickinson and Charlotte Bronte; the waters get a lot murkier when trying to assess how they considered their own identities. We have always been here is something queers (myself included) often say, but we have not always conceived of ourselves in the same way, using the same language.

A history of queer language is a history of queer people, especially queer Americans. It marks how we understood ourselves, how we were understood by institutions: how we wrote and rewrote ourselves, how we adapted, how we moved through space and absorbed and reconfigured words to suit what we needed. The more I understand the way our words moved like water around stones, the more I understand where we came from.

Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer fills in so many gaps, insisting on a rich and distinct cultural context that refuses the kind of sweeping statements so many internet writers are prone to these days. Reading Ryan’s work, I walked away with a new appreciation for Walt Whitman, George Bernard Shaw, and so many others, for the rich relationship between queer neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Manhattan, for the fact that no history or identity can be simply condensed within 280 characters.

Still: there is a reason that seminal queer texts from even the early 20th century like EM Forster’s Maurice was published posthumously, that 1952’s The Price of Salt was first published under a pseudonym. To be queer—to be happy and queer, especially—in public came at a cost. To be queer was to be pornographic and obscene, at best; to be illegal and thrown in prison, at worst. Oscar Wilde’s trial for sodomy wasn’t so long ago.

We live in a time where visibility and legal recognition feels vital, just as, privately, I’ve been part of more than one conversation with groups of queers who question whether we want to put our sexual orientation or gender identity on a census, whether we want to publicly register ourselves with the current administration. Why make it any easier for them than it has to be, you know?

To be queer in 2019 is not what it was to be queer in 1969 at Stonewall is not what it was to be queer in 1855, when Walt Whitman published Leaves of Grass and wrote,

As if a phantom caress’d me, I thought I was not alone, walking here by the shore; But the one I thought was with me, as now I walk by the shore—the one I loved, that caress’d me, As I lean and look through the glimmering light—that one has utterly disappear’d, And those appear that are hateful to me, and mock me

Words and identities are shifting; it’s the action, and the legacy of text, that remains.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Jeanna Kadlec

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Lit Hub Weekly: May 6 - 10, 2019

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

The Unspeakable Linguistics of Camp

When gay and lesbian people had to invent their own languages with which to talk with each other, camp led the way.

Not so long ago, there was a oppressed tribe of people, scattered throughout a larger population, whose very existence was seen as so taboo, so immoral, so illegal, they had to invent their own language to talk with each other , hidden in plain sight. This emerging secret code was not only how they could find each other and show they belonged to the same subculture. It was also a very necessary cloak of protection against public discovery from people who were outside the group. Because on the other side of that lay the real threat of not just discrimination, but ostracization from good society, the loss of livelihoods, and even imprisonment or death.

The Need for a Secret Language

This was the fraught experience for many gay men, lesbians, and others who identified as queer during a time when same-sex sex was a crime. Equal rights issues are still far from resolved , even in countries where it’s long been decriminalized. In those places in the world where it’s still socially unacceptable or a capital crime, punishable by death, innovative language use in queer communities is not an in-joke or a bit of fun—it might be a key survival tactic.

Audio brought to you by curio.io

Polari (or Parlary, Palarie, as it’s also known, from the Italian “to talk”) is one lost language from Britain that became primarily associated with gay men (and to a lesser extent with lesbians). Its rich, rollicking, madcap patchwork linguistics was cobbled out of the threads of the secret “anti-languages” used by subcultures on the very edges of society, the low slang used by thieves, itinerant sailors, fishmongers, travelling circus performers, beggars, prostitutes, and (of course) theater people. Seemingly a linguistic home to everyone from everywhere, it creatively mixed in elements from Elizabethan thieves’ cant, the Italian-influenced carnival speech Parlyaree, Cockney rhyming slang, backwards slang, Yiddish, and Lingua Franca, the sailors’ argot.

Here’s David Bowie having a go at using it in his 2016 release of “Girl Loves Me” (and if you want to vada a translation, luckily there’s a bona app for that):

Cheena so sound, so titty up this Malchick, say Party up moodge, nanti vellocet round on Tuesday Real bad dizzy snatch making all the omies mad, Thursday Popo blind to the polly in the hole by Friday

According to Paul Baker, foremost linguistic expert in Polari, this secret language, far from being a colorful fad that just fell out of fashion (before being cryptically revived by Bowie) was vital to the many gay men who used it to communicate with each other under the radar—at least until homosexuality stopped being a crime in the late sixties, rendering the secret language somewhat obsolete. (It was also no longer so secret, particularly after it appeared on radio, popularized by two very campy comedians ).

The effects of Polari still linger on in mainstream English, in British slang words such as “naff,” “blag,” “scarper,” which is no mean feat for a secret language virtually nobody knows anymore. And that’s the surprising thing. This happens a lot with language created by marginalized groups such as the gay community.

As these initially secret linguistic codes grew richer, celebrating a fractured, hidden subculture and its vibrant aesthetics, they slowly bled their way into the very same mainstream that didn’t want them to exist, exerting a major linguistic influence on pop culture. Many contemporary memes and slang terms in mainstream pop culture such as “yas Queen” and “throwing shade,” for example, were appropriated from the unique linguistic practices of the queer community, often coined decades before. It’s a phenomenon that seems to replicate across different cultures, such as Bahasa Gay, a gay speech style of Indonesia, which has made its way into mainstream Indonesian life without the public being particularly aware that gay people even exist. How does this happen?

The spreading of these sorts of gay speech styles might be thanks to drag queens and other queer performers. The above clip for example, from 1938’s screwball comedy Bringing Up Baby , shows what is probably the first appearance of the word “gay” with a decidedly queer, cross-dressing meaning in a mainstream movie. Ad libbed by the reputedly bisexual Cary Grant, mainstream audiences would not have understood the slang term, and it passed right under the nose of the Hays Office, which strictly enforced the censorship of such unspeakable things as homosexual references in film. It wasn’t until the Stonewall Riots of 1969 (in which drag queens played a prominent role) that this slang meaning of “gay” really took hold in mainstream English.

There were other ways that queer performers changed the language. Time to spill the tea on what we might call “camp” linguistics.

What is Camp?

Susan’s Sontag’s much celebrated 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp'” brought awareness to this hard-to-describe emerging aesthetic of over-the-top yet ironic theatricality , attributing it to gay culture. There is probably nothing more camp than a drag performance, for all its love of spectacle.

In fact, we probably have Polari to thank for the word “camp” itself. Though there’s no definitive agreement on the etymology of the word “camp” , it’s highly possible it has its basis in Polari , perhaps from the Italian word campare, which means making something, such as art, stand out. But also apt for those who live for campy anthems, is its primary meaning, to live, to survive . Others believe it may have come from French camper , “to portray or pose.”

Not everyone can agree on what counts as camp. As Sontag put it, “the ultimate Camp statement: it’s good because it’s awful,” is an artful juxtaposition which seems made for the avant-garde. Perhaps it’s a case of “you know it when you see it,” and camp definitely intends to be seen, consumed, and shared. But Sontag also threw a bit of shade at its origins, demurring that “one feels that if homosexuals hadn’t more or less invented Camp, someone else would.”

Would they have? I wonder. What other subculture would have the drive and the expressive urgency to develop something as frivolously influential as camp? On the one hand, you have a socially stigmatized subculture in hiding, at risk of public exposure and abuse and, on the other, that same community’s fervent desire for theatrical, socially confronting gender-bending self-expression. This is all bound together by a colorfully snarky linguistic code that enabled secrecy but also a purely linguistic playfulness and sharp wit, for example in rhyming words like “kiki,” “peer queer,” and “fag hag.” Smells like drag queen spirit. So how did campy drag queens, often marginalized even within the queer community as simply one-note entertainers, become such an important linguistic influence? It’s clear there’s a lot more to drag queen culture than just frivolity.

The Homophile Backlash

In 1950s Britain, men were still being imprisoned for consensual homosexual acts, numbering over a thousand by mid-decade , trapped by undercover cops posing as gay men.

Across the pond in America, it was no better. In the years following the chaotic second world war, what Craig M. Loftin calls the “age of anxiety,” women had experienced newfound freedoms as a central part of the workforce and masculinity was trying to find its way home. The powers that be were in a gender-confused, blaming mood. The hysterical McCarthyist hunt for reds under the bed eventually led to U.S. Senate hearings to weed out more lavender types from public life. Thousands of gay men and lesbians were purged from government agencies and the military, spied on, arrested, and severely penalized, their careers and futures destroyed.

Many LGBTQ people, especially in the more staid, white-collar middle class, decided that merging into the mainstream was the better part of valour, quietly passing as straight by eliminating any outrageous mannerisms or revealing language quirks that strayed from the commonplace, and advocating for eventual social acceptance through good behavior. This gender-conforming group, known as the homophile movement, directed their gender anxieties and anger toward more flamboyant members of the queer subculture who were out there in the open, giving the rest of them a fabulously bad name. They resented the too-obvious camp aesthetic of “swishes” ( a sometime derogatory diss before Katy Perry got to it ), men who played with gender identity by appropriating feminine characteristics, including campy, feminine speech patterns, as well as drag performers. The terms “fairy,” “nelly,” “queen,” and “faggot” were often used in the same negative way to refer to overtly effeminate men.

Different types of gayspeak across cultures and countries often use “she-ing”, feminizing people or objects by using feminine pronouns for example, sometimes as another way to hide taboo relationships from public view. Mocking, feminizing slang such as “Lucy Law” (for the police) and “Vera Vice” (for the vice squad) disrupt gender norms (though some have argued it also perpetuates misogyny). At any rate, this near-universal linguistic practice of gay cultures everywhere, along with other “swish” stereotypes, was strenuously rejected by the masculine-identified homophile movement of the 50s and 60s as a perversion of language as well as social norms.

One of the few prominent homophile magazines of the day, ONE, frequently featured anti-swish sentiments from their gay readers, which largely internalized public anxieties and prejudices about overt homosexual stereotypes: “The flaming faggot who swishes up Lexington Avenue in New York City screaming and calling attention to his eccentricities sets back homosexuality,” “I think that these people who call each other ‘she,’ etc., are sick,” and finally “STAMP OUT QUEENS!”

To visibly identify as “queer” at this time seemed not only highly reckless, it was potentially life-ruining. Basically, you wouldn’t have wanted to do what drag queens do best and look fishy in public. Abuse was directed at this often-stigmatized group not just by the suspicious public but their own queer community, using the same arguments and stereotypes to keep them in place.

Camp Goes Mainstream

And yet the swishes and the drag queens who dared to push for visibility were often the ones with the most to lose, not only because they were in the front lines of exposure, easily targeted during bar raids and riots. Swishes were very often from the lower working classes or African American and Latino. As drag queens, they were unusually free to perform other identities, not just of gender, but of race and class, as Rusty Barrett’s study on African-American drag queens in Texas shows . An African-American drag queen, such as the famous Lady Chablis in John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, could expertly perform the mannerisms, language, and other stereotypes of an upper class white woman, a role that would otherwise be barred to her. Drag art certainly could make onlookers question their gender, race, and class assumptions, while immersing in a seamless performance of language and manner. And what better way to protect a private self than behind the safety of an over-the-top, ironic performance?

It was the radical spectacle of camp, increasingly enjoyed as a form of mainstream entertainment by a general audience, through the startling success of shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race , or popular polari-speaking camp comedians, cross-dressing actors, and musicians of the past, that edged once hidden elements of queer culture into the open and caused an explosion of neologisms to be adopted into mainstream pop culture. Often, those linguistic origins are lost as they’re picked up and shared more widely. Though the unique speech of drag queens emerged as a way to show belonging in a marginalized subculture, it may soon belong to a more mainstream audience who may not even be aware of its long, unspeakable history.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- Archival Adventures in the Abernethy Collection

The Development of Central American Film

Remembering Maud Lewis

Exploring the Yardbird Reader

Recent posts.

- Before Palmer Penmanship

- Nightclubs, Fungus, and Curbing Gun Violence

- Elephant Executions

- Scaffolding a Research Project with JSTOR

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Effects of Gay language in understanding the meaning of English words

Related Papers

Kimberly H Cabantug

Denis Provencher

Gender Approaches in the Translation Classroom

Irene Ranzato

This chapter illustrates the results of a translation test/questionnaire aimed at verifying how MA and BA students of translation (English to Italian) responded to the translation of dubbed films and TV series featuring characters using words related to homosexuality. The study aims at shedding light on the degree of sensitivity and overall response to homosexuality-related issues by University students and on the strategies adopted both by the official adapters and by the students to bypass the objective imbalance between the English and Italian respective homosexual lexicons (Ranzato 2012). More in general, the experience is meant to enhance students' awareness of gender-related issues in the translation classroom. Go to https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9783030043896

The International Encyclopedia of Linguistic Anthropology

Studies of the language of queer speakers – i.e. speakers whose gender and/or sexual identities fall outside of the normative heterosexual binary – have followed a trajectory largely mirroring evolutions in the greater field of sociolinguistics. While early sociolinguistic research searched for large‐scale linguistic differences patterning according to broad macro‐social demographic differences, the field in recent decades has increasingly implemented ethnographic, context‐sensitive analyses exploring how individuals use language to construct and project a range of locally meaningful identities on the ground. In the same way, studies of speakers with queer identities were initially concerned with discovering linguistic differences between queer and straight speakers, but have increasingly come to emphasize the diversity of queer voices in various contexts and how these voices contribute to the construction of a range of queer identities.

Rusty Barrett

The Normal Lights

Helen Espeno Rosales

Digital Press Social Sciences and Humanities

Anggi Gustara

Shannon Weber

Suzan Tuğba Öner

Linguistic Perspectives on Sexuality in Education: Representations, Constructions and Negotiations

Łukasz Pakuła

Back in 2018 I witnessed an instance of verbal behaviour which-I believe-would be categorised as hate speech, for instance, in the UK, yet regrettably remains unpenalised in the Polish legal system. A social media group intended for teachers of English as a foreign language (EFL) in Poland, I used to be a member of, featured a post asserting that non-heteronormative students should not be treated on a par with the heterosexual majority. It contained denigrating and devaluating claims about such students. What is more bewildering and saddening, it was authored by a teacher. Would you expect an instant reprimand on the part of the group community defending the rights of such student minority? I certainly did. For this reason, I was rather taken aback to read only a few moderately critical comments that were followed with somewhat vehement replies by the author becoming even more verbally aggressive. My reaction was instinctive: to label the behaviour appropriately, refute the ludicrous argumentation and direct the fellow group members to relevant research literature. If I recall correctly, I was supported by merely one more member and at the same time chastised by the group admin for "name calling", that is, using the word homophobe. In an ensuing private conversation with a group administrator, I was advised of the fact that the group was not intended for "social polemics" as it was conceived of as a platform fostering discussions on language teaching only, as if language could be taught in a social vacuum. Deeming it pertinent to the case in point, I indefatigably pursued this subject by creating a new post informing fellow teachers of the insidiously perilous dangers of maintaining uncritical attitude towards using homophobic language in educational settings, including acts of suicide, and cross-referenced a report on gender and sexuality in the Polish EFL I co-authored (Pakuła et al. 2015). This was met with a preventive measure, according to the admin, of deleting it in order to avoid an "ideological war" on the forum as this was "a space for people of divergent worldviews". I can only recall my feeling of disillusionment and disappointment. In the report I mention, one of the interviewees who had been an EFL textbook reviewer for a number of years christened EFL practitioners members of a vanguard group due to their insightful knowledge not only of the language per se but also of the broader socio-cultural context. This, however, at least in this case, can be only cast away as mere wishful-thinking. A vision of an inclusively oriented teacher need not be utopian, though. However, in order to arrive at this, a certain set of criteria need to be fulfilled. First and foremost, the vital role of teacher training programmes needs to be widely acknowledged (Bellini 2012, Paiz this volume). They ought to incorporate explicit content related to LGBT+ students and

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Pragmatics Research

Tira Nur Fitria

Imam Syafi'i

Revista do Instituto Geológico

Maria Cristina Motta Toledo

Zeke McKinney

justice sibiri

Alfred Nji Fonteh

Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering

Ajay Kumar Dwivedi

Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition

Yannick Berthoumieu

International Journal of Control

Michael Tchaikovsky

Crystiane Cardoso

International Journal of Francophone Studies

Siona Wilson

E3S Web of Conferences

Rista Hernandi Virgianto

Science Education

Sherry A . Southerland

Frontiers in Immunology

Danique van Rijswijck

Student Journal of Occupational Therapy

Thelander Hill

BMC genomics

Joanna Puławska

Laura Galvis

Luiz Fernando

SPIE Proceedings

George Angeli

ANA CARIDAD SERRANO PATTEN

Proceedings of the 5th World Congress on Mechanical, Chemical, and Material Engineering

Jacek Nowaczyk

Biochemical Journal

Arturo Rojo-Domínguez

Mandla Nyathi

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

20 Must-Read Queer Essay Collections

Laura Sackton

Laura Sackton is a queer book nerd and freelance writer, known on the internet for loving winter, despising summer, and going overboard with extravagant baking projects. In addition to her work at Book Riot, she reviews for BookPage and AudioFile, and writes a weekly newsletter, Books & Bakes , celebrating queer lit and tasty treats. You can catch her on Instagram shouting about the queer books she loves and sharing photos of the walks she takes in the hills of Western Mass (while listening to audiobooks, of course).

View All posts by Laura Sackton

I love essay collections, and I love queer books, so obviously I love queer essay collections. An essay collection can be so many things. It can be an opportunity to examine one particular subject in depth. Or it can be a wonderful messy mix of dozens of themes and ideas. The books on this list are a mix of both. Some hone in on an author’s own life, while others look outward, examining current events, history, and pop culture. Some are funny, some are very serious, and some are decidedly both.

In making this list, I used two criteria: 1) queer authors and 2) queer content. There are, of course, plenty of wonderful essay collections out there by queer authors that aren’t about queerness. But this list focuses on essays that explore queerness in all its messy glory. You’ll also find essays here about many other things: tornadoes, step-parenthood, the internet, tarot, activism, online dating, to name just a few. But taken together, the essays in each of these books add up to a queer whole.

I limited myself to living authors, and even so, there were so many amazing queer essay collections I wanted to include but couldn’t. This is just a drop in the bucket, but it’s a great place to start if you need more queer essays in your life — and who doesn’t?

Personal Queer Essay Collections

How to Write An Autobiographical Novel by Alexander Chee

It’s hard for me to put my finger on the thing that elevates an essay collection from a handful of individual pieces to a cohesive book. But Chee obviously knows what that thing is, because this book builds on itself. He writes about growing roses and working odd jobs and AIDS activism and drag and writing a novel, and each of these essays is singularly moving. But as a whole they paint a complex portrait of a slice of the writer’s life. They inform and converse with each other, and the result is a book you can revisit again and again, always finding something new.

I Hope We Choose Love by Kai Cheng Thom

In this collection of beautiful and thought-provoking essays, Kai Cheng Thom explores the messy, far-from-perfect realties of queer and trans communities and community movements. She writes about what many community organizers, activists, and artists don’t want to talk about: the hard stuff, the painful stuff, the bad times. It’s not all grim, but it’s very real. Thom addresses transphobia, racism, and exclusion, but she also writes about the particular joys she’s found in creating community and family with other queer and trans people of color. This is a must-read for anyone involved in social justice work, or immersed in queer community.

Here For It by R. Eric Thomas

If you enjoy books that blend humor and heartfelt wisdom, you’ll love this collection. R. Eric Thomas writes about coming of age as a writer on the internet, his changing relationship to Christianity, the messy intersections of his queer Black identity. It’s a lovey mix of grappling and quips. It’s full of pop culture references and witty asides, as well as moving, vulnerable personal stories.

The Rib Joint by Julia Koets

This slim memoir-in-essays is entirely personal. Although Koets does weave some history, pop culture, and religion into the work — everything from the history of organs to Sally Ride — her gaze is mostly focused inward. The essays are short and beautifully written; she often leaves the analysis to the reader, simply letting distinct and sometimes contradictory ideas and images sit next to each other on the page. She writes about her childhood in the South, the hidden and often invisible queer relationships she had as a teenager and young adult, secrets and closets, and the tensions and overlaps between religion and queerness.

I Can’t Date Jesus by Michael Arceneaux

This is another fantastic humorous essay collection. Arceneaux somehow manages to be laugh-out-loud funny while also delivering nuanced cultural critique and telling vulnerable stories from his life. He writes about growing up in Houston, family relationships, coming out, and so much more. The whole book wrestles with how to be a young Black queer person striving to make meaning in the world. His second collection, I Don’t Want to Die Poor , is equally wonderful.

Tomboyland by Melissa Faliveno

If you’re wondering, this is the book that contains an essay about tornadoes. It also contains a gorgeous essay about pantry moths (among other things). Those are just two of the many subjects Faliveno plumbs the depths of in this remarkable book. She writes about gender expression and how her relationship with gender has changed throughout her life, about queer desire and family, about Midwestern culture, about place and home, about bisexuality and bi erasure. Her far-ranging essays challenge mainstream ideas about what queer lives do and do not look like. She asks more questions than she answers, delving into the murky terrain of desire and identity.

Something That May Shock and Discredit You by Daniel M. Lavery

Is this book even an essay collection? It is, and it isn’t. Some of these pieces are deeply personal stories about Lavery’s experience with transition. Others are trans retellings of mythology, literature, and film. All of it is weird and smart and impossibly to classify. Lavery examines the idea of transition from every angle, creating new stories about trans history, trans identity, and transformation itself.

Brown White Black by Nishta J. Mehra

If there’s one thing I love most in an essay collection, it’s when an author allows contradictions and messy, fraught truths to live next to each other on the page. I love when an essayist asks more questions than they answer. That’s what Mehra does in this book. An Indian American woman married to a white woman and raising a Black son, she writes with openness and curiosity about her particular family. She explores how race, sexuality, gender, class, and religion impact her life and most intimate relationships, as well as American culture more broadly.

Blood, Marriage, Wine, & Glitter by S. Bear Bergman

This essay collection is an embodiment of queer joy, of what it means to become part of a queer family. Every essay captures some aspect of the complexity and joy that is queer family-making. Bergman writes about being a trans parent, about beloved friends, about the challenges of partnership, about intimacy in myriad forms. His tone is warm and open-hearted and joyful and celebratory.

Forty-Three Septembers by Jewelle Gómez

In these contemplative essays, Jewell Gómez explores the various pieces of her life as a Black lesbian, writing about family, aging, and her own history. Into these personal stories she weaves an analysis of history and current events. She writes about racism and homophobia, both within and outside of queer and Black communities, and about her life as an artist and poet, and how those identities, too, have shaped the way she sees the world.

Pass With Care by Cooper Lee Bombardier

Set mostly against the backdrop of queer culture in 1990s San Francisco, this memoir in essays is about trans identity, being an artist, masculinity, queer activism, and so much more. Bombardier brings particular places and times to life (San Francisco in the 1990s, but other places as well), but he also connects those times and experiences to the present in really interesting ways. He recognizes the importance of queer and trans history, while also exploring the possibilities of queer and trans futures.

Care Work by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

This is a beautiful, rigorous collection of essays about disability justice centering disabled queer and trans people of color. From an exploration of the radical care collectives Piepzna-Samarasinha and other queer and trans BIPOC have organized to an essay where examines the problems with the “survivor industrial complex,” every one of these pieces is full of wisdom, anger, transformation, radical celebration. It challenged me on so many levels, in the best possible way. It’s a must read for anyone engaged in any kind of activist work.

I’m Afraid of Men by Vivek Shraya

I’m cheating a little bit here, because technically I’d classify this book as one essay, singular, rather than a collection of essays. But I’m including it anyway, because it is brilliant, and because I think it exemplifies just what a good essay can do, what a powerful form of writing it can be. By reflection on various experiences Shraya has had with men over the course of her life, she examines the connections and intersections between sexism, transmisogyny, toxic masculinity, and sexual violence. It’s a heavy read, but Shraya’s writing is anything but. It’s agile and graceful, flowing and jumping between disparate thoughts and ideas. This is a book-length essay you can read in one sitting, but it’ll leave you with enough to think about for many days afterward.

Gender Failure by Ivan E. Coyote and Rae Spoon

In this collaborative essay collection, trans writers and performers Ivan E. Coyote and Rae Spoon play with both gender and form. The book is a combination of personal essays, short vignettes, song lyrics, and images. Using these various kinds of storytelling, they both recount their own particular journeys around gender — how their genders have changed throughout their lives, the ways the gender binary has continually harmed them both, and the many communities, people, and experiences that have contributed to joyful self-expression and gender freedom.

The Groom Will Keep His Name by Matt Ortile

Matt Ortile uses his experiences as a gay Filipino immigrant as a lens in these witty, insightful, and moving essays. By telling his own stories — of dating, falling in love, struggling to “fit in” — he illuminates the intersections among so many issues facing America right now (and always). He writes about the model minority myth and many other myths he told himself about assimilation, sex, power, what it means to be an American. It’s a heartfelt collection of personal essays that engage meaningfully, and critically, with the wider world.

Wow, No Thank You by Samantha Irby

I’m not a big fan of humorous essays in this vein, heavy on pop culture references I do not understand and full of snark. But I absolutely love Irby’s books, which is about the highest praise I can give. I honestly think there is something in here for everyone. Irby is just so very much herself: she writes about whatever the hell she wants to, whether that’s aging or the weirdness of small town America or snacks (there is a lot to say about snacks). And whatever the subject, she’s always got something funny or insightful or new or just super relatable to say.

Queer Essay Anthologies

She Called Me Woman Edited by Azeenarh Mohammed, Chitra Nagarajan, and Aisha Salau

This anthology collects 30 first-person narratives by queer Nigerian women. The essays reflect a range of experiences, capturing the challenges that queer Nigerian women face, as well as the joyful lives and communities they’ve built. The essays explore sexuality, spirituality, relationships, money, love, societal expectations, gender expression, and so much more.

Untangling the Knot: Queer Voices on Marriage, Relationships & Identity by Carter Sickels

When gay marriage was legalized, I felt pretty ambivalent about it, even though I knew I was supposed to be excited. But I have never wanted or cared about marriage. Reading this book made me feel so seen. That’s not to say it’s anti-marriage — it isn’t! It’s a collection of personal essays from a diverse range of queer people about the families they’ve made. Some are traditional. Some are not. The essays are about marriages and friendships, parenthood and siblinghood, polyamorous relationships and monogamous ones. It’s a book that celebrates the different forms queer families take, never valuing any one kind of family or relationship over another.

Nonbinary: Memoirs of Gender and Identity Edited by Micah Rajunov and Scott Duane

This book collects essays from 30 nonbinary writers, and trans and gender-nonconforming writers whose genders fall outside the binary. The writers inhabit a diverse range of identity and experience in terms of race, age, class, sexuality. Some of the essays are explicitly about gender identity, others are about family and relationships, and still others are about activism and politics. As a whole, the book celebrates the expansiveness of trans experiences, and the many ways there are to inhabit a body.

Moving Truth(s): Queer and Transgender Desi Writings on Family Edited by Aparajeeta ‘Sasha’ Duttchoudhury and Rukie Hartman

This anthology brings together a collection of diverse essays by queer and trans Desi writers. The pieces explore family in all its shapes and iterations. Contributors write about community, friendship, culture, trauma, healing. It’s a wonderfully nuanced collection. Though there is a thread that runs through the whole book — queer and trans Desi identity — the range of viewpoints, styles and experiences represented makes it clear how expansive identity is.

Looking for more queer books? I made a list of 40 of my favorites . If you’re looking for more essay collections to add to your list, check out 10 Must-Read Essay Collections by Women , and The Best Essays from 2019 . And if you’re not in the mood for a whole book right now, why not try one of these free essays available online (including some great queer ones)?

You Might Also Like

LGBTQ identity is shaped by language. So what words will describe “queer” in the future?

Editor’s note: What will the future hold for LGBTQ rights and representation? With this year’s Beyond Pride series, Mic looks forward to seeing how the radical changes in recent years will continue to transform our culture in the worlds of politics, business, entertainment and more. You can receive all these stories in your inbox by signing up here .

When William Leap was growing up in North Florida in the 1950s, the word “queer” was, as it was for so many kids at the time, a schoolyard taunt, an insult. Leap would go on to become a linguist and, in the 1990s, one of the key originators of the study of queer language, or “lavender linguistics.” But even as he watched activists in the ‘80s and ‘90s reclaim the word “queer”as they organized against the AIDS epidemic, and queer theorists using it in academia, the word still didn’t feel right to him, Leap said in an interview. He couldn’t shake his personal association with the word “queer,” a slur of his childhood.

It wasn’t until the mid-aughts, Leap said, that he first began to see the personal value of the word queer. “I really didn’t want to associate with the term, because it wasn’t a term that people I worked with used,” Leap said. “But [in the] mid-2000s my own thinking started to change and I saw a lot of reasons for thinking about the usefulness of the term. Particularly because it moves us beyond, as it’s supposed to, certain kinds of distinctions. And that becomes helpful.”

By that point, a new generation of young LGBTQ people were already growing up with the word “queer” as an identity category, and feeling comfortable using it about themselves. It’s gone from a subversive, radical identifier to a term so widely used and broadly applied that, in 2016, Vice published a story with the title, “Can Straight People Be Queer?”

And that’s just one single word in the LGBTQ lexicon — there are other identity terms that feel similarly, and perhaps even more suddenly, ubiquitous. A 2017 study by the advocacy group GLAAD found that millennials were more than twice as likely as baby boomers to identify as LGBTQ, but less likely than older LGBTQ generations to use the words “gay” or “lesbian” to describe themselves, leading the group to conclude that “millennials appear more likely to identify in terminology that falls outside those previously traditional binaries.”

That survey didn’t even include Generation Z, which is shaping up to be queerer and more gender diverse than millennials. A 2016 report from the J. Walter Thompson Innovation Group found that more than half of Gen Z-ers said they know someone who uses gender-neutral pronouns such as “they” or “ze,” and less than half of the group said they identified as “exclusively heterosexual.”

Even beyond the terms used to describe sexuality or gender identity, young LGBTQ people trade slang on Twitter or Tumblr or hyperspecific subreddits. With queer language feeling like it’s changing and spreading faster than ever, jumping into the mainstream through viral memes and reality TV, what will queer language look like by the year 2030? When today’s teens are LGBTQ adults, will their language be totally unfamiliar to their LGBTQ forbearers?

How queer language spread then and now

The LGBTQ communities may be unique in their heterogeneity — queer people can be any race, class, gender or religion, and many come to their queer identities later in life. Still, among the vast and varied LGBTQ communities in the United States, there exists, if not quite a shared language, then a shared lexicon of words and phrases. But those words haven’t always been the same. Some have fallen out of use and others have emerged; some have even taken on new meanings.

For much of the 20th century, queer language spread person to person. In the 1940s, Leap said, the Second World War ushered in somewhat of a gay slang boom as soldiers met and mingled. They adapted the military habit of derisively addressing men as if they were women and used it playfully, calling each other, and themselves, “she” and “her,” or “bitch.”

They used the slang in their letters, Leap said, both to convey affection and meaning and to make it more difficult for unknowing straights to decode. In the 1950s, with the rising popularity of recreational travel, gay and lesbian slang spread again from person to person. Words and phrases also circulated through specialized gay and lesbian magazines of the era, but still, only as fast as the postal service could go.

But as the 20th century gave way to the 21st, the advent of the internet, and especially social media, suddenly allowed queer people to find each other and swap jokes from miles away, at lightening speed.

“Though certain expressions have been spread throughout the LGBT+ community by word of mouth forever, it appears as though the main culprits now are social media and TV,” queer linguist Darrin Miller, who has written about the intersection of queer language and the internet, said in an email interview in May. “Take ‘yaaass’ [and] ‘yaaass queen’ ... which originated from black [and ballroom] culture.” Miller said that the memes and videos online boosted “yaaass” to mass audiences, “and now it’s everywhere.”

More LGBTQ representation on television and in film has accelerated the dispersion of queer words and slang. Consider the example of the phrase “throwing shade.” At first it traveled the old-fashioned way, Miller said. “Throwing shade,” like so many other phrases in widespread use in the queer community, originated in the Southern black community, Miller pointed out, before making its way up to the New York City ball scene, where it was used by ballroom performers, primarily people of color. But it wasn’t until its frequent use on the drag-queen competition show Ru Paul’s Drag Race, which first premiered in 2009, that “throwing shade” was really flung into mainstream use, even earning itself a 2015 trend piece in the New York Times .

This pattern, incidentally, is not uncommon. Both Miller and Leap mentioned that a number of popular gay slang terms originated with people of color before entering wider use in the LGBTQ communities. “I would say there is a lot of adoption (or cultural appropriation) of Southern black expressions by particularly the ‘G’ portion of the queer community,” Miller said. Whether today’s queer youth will collectively reckon with that appropriation, and acknowledge their slang’s origins, remains to be seen.

But those changes to the way queer language spreads, ushered in by the internet and meme culture, are here to stay. The current generation of queer teenagers, who will be queer adults in 2030, can watch Drag Race at home, or can find likeminded young people in specialized online communities, another source for new terms.

“Take a look at how many subreddits there are that are dedicated to individual subgroups of the LGBT+ community,” Miller said. “I’ll tell you this much: There are at least two just for asexual individuals, and these are highly active communities. ... What this means for queer people is that we have a huge supportive cohort that we can come home to, a safe haven online where we can speak about anything we want without fear of repercussions. Expressions are spawned from this discourse, which is highly concentrated in a particular topic, and sometimes these expressions are carried out into the real world or crossed over into other online subcommunities.”

In an email interview in May, linguist Lex Konnelly, a Ph.D. student at the University of Toronto, brought up the example of “enby,” a word that formed from the gender descriptor “nonbinary” and traveled through internet communities on various social media platforms.

But, with some exceptions, the “new” words in use today are rarely as new as they seem. They may be older phrases that happened to “go viral,” or words that just went unnoticed by the hetero-world until more recently.

“A lot of these supposedly new identity terms have actually existed for some time: For example, ‘genderqueer , ’ which many noncommunity members consider to have emerged within the last few years, has been in use since at least the late 1990s,” Konnelly said. “But words often don’t gain wider circulation outside of specific local communities and into the ‘mainstream’ until later, which can lead to the impression that they’re ‘brand new’ concepts or terms.” Of course, the identities those terms refer to have always existed, Konnelly pointed out — it’s just that we now have access to more nuanced language to describe them.

So what can we expect by 2030?

The dominance of the internet’s effect on queer language will likely only increase. Today’s queer teens “live on the internet and communicate through social media, so I think that we will continue to see memefied expressions entering various subsets of the queer community through social media, in conjunction with reality TV,” Miller said. Miller added that, while many of today’s queer slang terms will likely still be around by 2030, there will certainly be new ones that “may emerge through viral videos and memes.” And other “pre-existing expressions” might hit the big time through a viral video or meme.

But not every expression has staying power. “I’m going to shoot myself in the foot later by saying this, but ‘yaaass kween’ reminds me of ‘wazzaaaap’ from the old Budweiser commercials,” Miller said. “I use it, and my friends use it, [but] I don’t think it will last forever. The next generation is more dynamic. I think they will come up with something more clever to express support and admiration.”

Konnelly suggested that today’s queer teens are likely already more thoughtful about their language use, especially when it comes to gender diversity. “We recognize in sociolinguistics that younger people tend to be on the vanguard of linguistic changes, and part of this is because they’re at the forefront of cultural changes as well,” Konnelly said. For todays’ queer teenagers, that might manifest in more dextrous and varied pronoun use.

Younger people are more comfortable using “neopronouns,” or nonbinary pronouns like “ze,” than older generations, Konnelly said, in part because they’ve had the experience of growing up with the knowledge “that you can use the pronouns that feel right for you,” and may feel less inherent judgement.

Ose Arheghan, a queer, nonbinary 17-year-old who was named the 2017 GLSEN student advocate of the year, said that, for them, language is “of the utmost importance.”

“I think language is important because it gives people license to understand either the person that they are or the person that they’re trying to accept,” Arheghan said. “Not everybody knows what things mean, and so when we talk about queerness, that means a lot of different things to different people. It can mean queerness in terms of sexuality, it can mean queerness in terms of gender, it can mean queerness in terms of being other than cis-heteronormativity. And so, when it comes to language, the idea of using terms to pinpoint exactly what somebody identifies as, what somebody embodies as a person — it’s so important.”

Along with more fluency in pronouns and nonbinary gender identities, 2030 might bring a decline in gendered slang, like that trend among cis gay men to use gendered words like “girl” or “sis,” a variety of slang that Leap connected to World War II. But what about gendered “in-group identity terms” like “fag” and “dyke,” or words that refer to subcommunities within queer culture, like “bear,” “butch” or “twink.”

“They’re not really ‘slang’ in the way that ‘girl’ is, and so whether or not they stick around is more dependent on whether people identify with them,” Konnelly said. “In that sense, I don’t think that they’ll totally lose relevancy, though it does seem to me that words like ‘fag’ and ‘dyke’ (which have historically been used by gay men and lesbians, respectively) are losing ground to the un-gendered ‘queer.’”

Arheghan said the reason they identify as queer, “as opposed to bisexual or pansexual,” is because their attraction isn’t based on gender. “Almost all of our language to describe sexuality, it’s based on gender. So you’re attracted to somebody because they’re the same gender as you, or you’re attracted to somebody because they’re a different gender as you, or you’re attracted to people of multiple genders ... and so if your attraction isn’t based on gender then there isn’t language for that. And so that’s why I use the word queer.”

Even as the next generation of queer young people move away from gendered terms, we could see words like “butch” and “bear” stick around but lose their specifically gendered associations. Konnelly said that it’s possible the meanings of those words could shift, as has already begun to happen with the word “femme.” Historically, Konnelly said, “femme” referred to a lesbian with a conventionally feminine presentation.

“Now, femme is used as a descriptor of all kinds of genders to indicate connection to a queer femininity: for example, plenty of nonbinary folks identify as femme,” Konnelly said. “It’s possible something similar could happen for ‘butch.’ As the queer community continues to chip away at the façade of the gender binary, I think we’ll see more and more creative and playful combinations of terms that we have thought of as referring to one specific gender: Who says someone can’t be a femme bear, for example?”

But Arheghan said they do know some people in their generation who choose to use what have long been considered gendered terms to describe their identities. “I know tons of people who still identify as 100% gay or 100% lesbian,” Arheghan said. “For most people, queer is just an umbrella term for the LGBTQ community, and that’s the most common way I see ‘queer’ being used in my daily life.”

That’s not to say Arheghan hasn’t noticed a generational divide when it comes to certain words. Arheghan said that, in meeting older LGBTQ people through SAGE , a national organization for LGBTQ seniors, they’ve encountered older queer women who identity as dykes, and men who call themselves sissies or fags. “That’s another way of reclaiming slurs [but] in my high school, if somebody identified as a faggot, people would be shocked. People would be uncomfortable. I don’t know if those are terms that are going to stay. I know ... people still call themselves dykes, but it’s more like slang than it is an identification.”

Moving toward inclusion

So what else can we expect from the next generation of queer people? They might also do a better job than past generations of holding each other, and people outside of the community, accountable, Konnelly said. “The younger generations will probably continue to demand better from people inside and outside of the queer community, too — pushing harder for the recognition of gender diversity ... and just in general challenging the linguistic status quo and advocating for queer people’s linguistic self-determination in all its forms,” Konnelly said.

For Arheghan, who is headed to college in the fall, their hope for 2030 seemed to be that queer language would trend toward inclusion — a broader view of what androgyny can be, more acknowledgment of black queer communities that originated much of queer slang and also a wider understanding of the word trans.

“The way that we talk about the word ‘trans,’ I would really like to see that change in the next 12 years,” Arheghan said. “Right now, it’s really great that trans people are getting attention in the media ... but I think that now there’s the idea that, in order to identify as trans, you have to be either ‘male-to-female’ trans or ‘female-to-male’ trans. And that’s still really inundated with this idea of the gender binary.” Arheghan said they want to see the word “trans” come to colloquially include people who identify outside the gender binary, or as agender, genderqueer or genderfluid — without any extra explanation needed.

In all cultures, slang comes in and out of vogue, certain words shed and take on new connotations and entirely new terms spring up — and the shared lexicon that links LGBTQ people together is no different. But experts seem confident that whatever form the next generation’s queer language might take, they’ll likely shift the lexicon in ways we can’t yet predict. “We can only dream of the incredible, innovative things they’ll do,” Konnelly said.

- Themed Months

- What to Read When

- The First Book

- Funny Women

- Voices on Addiction

- We Are More

- Conversations With Writers Braver Than Me

- All Columns

- Poetry Book Club

- Letters in the Mail (from Authors!)

- Rumpus Store

- The Writer’s Welcome Kit

- Rumpus Shirts & Sweatshirts

- Rumpus Original

The Careless Language of Sexual Violence

- March 10, 2011

There are crimes and then there are crimes and then there are atrocities. These are, I suppose, matters of scale. I read an article in the New York Times about an eleven-year-old girl who was gang raped by eighteen men in Cleveland, Texas.

The levels of horror to this story are many, from the victim’s age to what is known about what happened to her, to the number of attackers, to the public response in that town, to how it is being reported. There is video of the attack too, because this is the future. The unspeakable will be televised.

The Times article was entitled, “Vicious Assault Shakes Texas Town,” as if the victim in question was the town itself. James McKinley Jr. , the article’s author, focused on how the men’s lives would be changed forever, how the town was being ripped apart, how those poor boys might never be able to return to school. There was discussion of how the eleven-year-old girl, the child, dressed like a twenty-year-old, implying that there is a realm of possibility where a woman can “ask for it” and that it’s somehow understandable that eighteen men would rape a child. There were even questions about the whereabouts of the mother, given, as we all know, that a mother must be with her child at all times or whatever ill may befall the child is clearly the mother’s fault. Strangely, there were no questions about the whereabouts of the father while this rape was taking place.

The overall tone of the article was what a shame it all was, how so many lives were affected by this one terrible event. Little addressed the girl, the child. It was an eleven-year-old girl whose body was ripped apart, not a town. It was an eleven-year-old girl whose life was ripped apart, not the lives of the men who raped her. It is difficult for me to make sense of how anyone could lose sight of that and yet it isn’t.

We live in a culture that is very permissive where rape is concerned. While there are certainly many people who understand rape and the damage of rape, we also live in a time that necessitates the phrase “rape culture.” This phrase denotes a culture where we are inundated, in different ways, by the idea that male aggression and violence toward women is acceptable and often inevitable. As Lynn Higgins and Brenda Silver ask in their book Rape and Representation , “How is it that in spite (or perhaps because) of their erasure, rape and sexual violence have been so ingrained and so rationalized through their representations as to appear ‘natural’ and inevitable, to women as men?” It is such an important question, trying to understand how we have come to this. We have also, perhaps, become immune to the horror of rape because we see it so often and discuss it so often, many times without acknowledging or considering the gravity of rape and its effects. We jokingly say things like, “I just took a rape shower,” or “My boss totally just raped me over my request for a raise.” We have appropriated the language of rape for all manner of violations, great and small. It is not a stretch to imagine why James McKinley Jr. is more concerned about the eighteen men than one girl.

The casual way in which we deal with rape may begin and end with television and movies where we are inundated with images of sexual and domestic violence. Can you think of a dramatic television series that has not incorporated some kind of rape storyline? There was a time when these storylines had a certain educational element to them , a la A Very Special Episode. I remember, for example, the episode of Beverly Hills, 90210 where Kelly Taylor discussed being date raped at a slumber party, surrounded, tearfully, by her closest friends. For many young women that episode created a space where they could have a conversation about rape as something that did not only happen with strangers. Later in the series, when the show was on its last legs, Kelly would be raped again, this time by a stranger. We watched the familiar trajectory of violation, trauma, disillusion, and finally vindication, seemingly forgetting we had sort of seen this story before.

Every other movie aired on Lifetime or Lifetime Movie Network features some kind of violence against women. The violence is graphic and gratuitous while still being strangely antiseptic where more is implied about the actual act than shown. We consume these representations of violence and do so eagerly. There is a comfort, I suppose, to consuming violence contained in 90-minute segments and muted by commercials for household goods and communicated to us by former television stars with feathered bangs.

While once rape as entertainment fodder may have also included an element of the didactic, such is no longer the case. Rape, these days, is good for ratings. Private Practice , on ABC, recently aired a story arc where Charlotte King, the iron-willed, independent, and sexually adventurous doctor was brutally raped. This happened, of course, just as February sweeps were beginning. The depiction of the assault was as graphic as you might expect from prime time network television. For several episodes we saw the attack and its aftermath, how the once vibrant Charlotte became a shell of herself, how she became sexually frigid, how her body bore witness to the physical damage of rape. Another character on the show, Violet, bravely confessed she too had been raped. The show was widely applauded for its sensitive treatment of a difficult subject.

The soap opera General Hospital is currently airing a rape storyline, and the height of that story arc occurred, yes, during sweeps. General Hospital , like most soap operas, incorporates a rape storyline every five years or so when they need an uptick in viewers. Before the current storyline, Emily Quartermaine was raped and before Emily, Elizabeth Webber was raped, and long before Elizabeth Webber, Laura, of Luke and Laura, was raped by Luke but that rape was okay because Laura ended up marrying Luke so her rape doesn’t really count. Every woman, General Hospital wanted us to believe, loves her rapist. The current rape storyline has a twist. This time the victim is a man, Michael Corinthos Jr., son of Port Charles mob boss Sonny Corinthos, himself no stranger to violence against women. While it is commendable to see the show’s producers trying to address the issue of male rape and prison rape, the subject matter is still handled carelessly, is still a source of titillation, and is still packaged neatly between commercials for cleaning products and baby diapers.

Of course, if we are going to talk about rape and how we are inundated by representations of rape and how, perhaps, we’ve become numb to rape, we have to discuss Law & Order: SVU , which deals, primarily, in all manner of sexual assault against women, children, and once in a great while, men. Each week the violation is more elaborate, more lurid, more unspeakable. When the show first aired, Rosie O’Donnell, I believe, objected quite vocally when one of the stars appeared on her show. O’Donnell said she didn’t understand why such a show was needed. People dismissed her objections and the incident was quickly forgotten. The series is in its twelfth season and shows no signs of ending anytime soon. When O’Donnell objected to SVU ’s premise, when she dared to suggest that perhaps a show dealing so explicitly with sexual assault was unnecessary, was too much, people treated her like she was the crazy one, the prude censor. I watch SVU religiously, have actually seen every single episode. I am not sure what that says about me.

I am trying to connect my ideas here. Bear with me.

It is rather ironic that only a couple weeks ago, the Times ran an editorial about the War on Women. This topic is, obviously, one that matters to me. I recently wrote an essay about how, as a writer who is also a woman, I increasingly feel that to write is a political act whether I intend it to be or not because we live in a culture where McKinley’s article is permissible and publishable. I am troubled by how we have allowed intellectual distance between violence and the representation of violence. We talk about rape but we don’t talk about rape, not carefully.

We live in a strange and terrible time for women. There are days, like today, where I think it has always been a strange and terrible time to be a woman. It is nothing less than horrifying to realize we live in a culture where the “paper of record” can write an article that comes off as sympathetic to eighteen rapists while encouraging victim blaming. Have we forgotten who an eleven-year-old is? An eleven-year-old is very, very young, and somehow, that amplifies the atrocity, at least for me. I also think, perhaps, people do not understand the trauma of gang rape. While there’s no benefit to creating a hierarchy of rape where one kind of rape is worse than another because rape is, at the end of day, rape, there is something particularly insidious about gang rape, about the idea that a pack of men feed on each other’s frenzy and both individually and collectively believe it is their right to violate a woman’s body in such an unspeakable manner.

Gang rape is a difficult experience to survive physically and emotionally. There is the exposure to unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, vaginal and anal tearing, fistula and vaginal scar tissue. The reproductive system is often irreparably damaged. Victims of gang rape, in particular, have a higher chance of miscarrying a pregnancy. Psychologically, there are any number of effects including PTSD, anxiety, fear, coping with the social stigma, and coping with shame, and on and on. The actual rape ends but the aftermath can be very far reaching and even more devastating than the rape itself. We rarely discuss these things, though. Instead, we are careless. We allow ourselves that rape can be washed away as neatly as it is on TV and in the movies where the trajectory of victimhood is neatly defined.

I cannot speak universally but given what I know about gang rape, the experience is wholly consuming and a never-ending nightmare. There is little point in pretending otherwise. Perhaps McKinley Jr. is, like so many people today, anesthetized or somehow willfully distanced from such brutal realities. Perhaps it is that despite this inundation of rape imagery, where we are immersed in a rape culture, that not enough victims of gang rape speak out about the toll the experience exacts. Perhaps the right stories are not being told or we’re not writing enough about the topic of rape. Perhaps we are writing too many stories about rape. It is hard to know how such things come to pass.

I am approaching this topic somewhat selfishly. I write about sexual violence a great deal in my fiction. The why of this writerly obsession doesn’t matter but I often wonder why I come back to the same stories over and over. Perhaps it is simply that writing is cheaper than therapy or drugs. When I read articles such as McKinley’s, I start to wonder about my responsibility as a writer. I’m finishing my novel right now. It’s the story of a brutal kidnapping in Haiti and part of the story involves gang rape. Having to write that kind of story requires going to a dark place. At times, I have made myself nauseous with what I’m writing and what I am capable of writing and imagining, my ability to go there .

As I write any of these stories, I wonder if I am being gratuitous. I want to get it right . How do you get this sort of thing right? How do you write violence authentically without making it exploitative? There are times when I worry I am contributing to the kind of cultural numbness that would allow an article like the one in the Times to be written and published, that allows rape to be such rich fodder for popular culture and entertainment. We cannot separate violence in fiction from violence in the world no matter how hard we try. As Laura Tanner notes in her book Intimate Violence , “the act of reading a representation of violence is defined by the reader’s suspension between the semiotic and the real, between a representation and the material dynamics of violence which it evokes, reflects, or transforms.” She also goes on to say that, “The distance and detachment of a reader who must leave his or her body behind in order to enter imaginatively into the scene of violence make it possible for representations of violence to obscure the material dynamics of bodily violation, erasing not only the victim’s body but his or her pain.” The way we currently represent rape, in books, in newspapers, on television, on the silver screen, often allows us to ignore the material realities of rape, the impact of rape, the meaning of rape.

While I have these concerns, I also feel committed to telling the truth, to saying these violences happen even if bearing such witness contributes to a spectacle of sexual violence. When we’re talking about race or religion or politics, it is often said we need to speak carefully. These are difficult topics where we need to be vigilant not only in what we say but how we express ourselves. That same care, I would suggest, has to be extended to how we write about violence, and sexual violence in particular.