January 1, 2014

11 min read

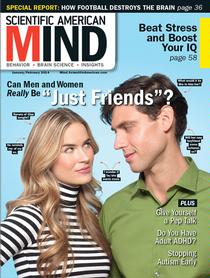

Can Men and Women Be Just Friends?

Attraction plays a significant role in opposite-sex friendship, but that doesn't make the bond less beneficial

By Carlin Flora

Kate and Dan met on the job in Boston, when they were in their early 20s. He thought she was attractive; she thought he was an arrogant jerk. At a work party, it came out that both had lost a parent in recent years, and a mutual feeling of “you must really get me” washed over them. A few years later, when they both found themselves in New York and single, the friendship ramped way up, into multiple-phone-calls-per-day, soul-baring, belly-laughing territory.

It is that feeling that someone truly understands us that lends friendship its power to ward off existential loneliness. Kate and Dan share it, yet their brand of friendship is often seen as suspect—as less than pure and true. Friendships between people who could conceivably date come with built-in suspense for onlookers: Will they get together, or won't they?

For philosophers and scientists alike, friendship has proved as difficult to pin down as love. And don't we, after all, love our close friends? Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and French essayist Michel de Montaigne in the 16th century felt that true friendship could exist only between virtuous men—holding up a high yet subjective bar that also happened to avoid women altogether. Plato, who lent his name to the term “platonic relationship” (or “platonic love”), described love as a window on true beauty, best kept free of venereal pursuits. Contemporary usage equates platonic relationships with amity rather than love, yet the origin of the term underscores friendship's multifaceted nature. All friendships begin with a spark of mutual attraction, and sometimes that attraction extends to the physical.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the scientific literature, many scholars have settled on a definition for friendship that was coined by psychologist Robert Hays of the University of California, San Francisco. He described the bond as “a voluntary interdependence between two persons over time that is intended to facilitate socioemotional goals of the participants and may involve varying types and degrees of companionship, intimacy, affection and mutual assistance.” Depending on those “types and degrees,” friendship can look an awful lot like courtship or love. This raises the question: Can heterosexual men and women be just friends, or is there always an inkling of desire?

The data suggest that a romantic spark is not uncommon among friends. Yet the truth is that all forms of companionship are complicated. We often shift our behaviors to try to nudge a relationship one way or another. Our actions only sometimes reflect the disinterested care and concern we assume must characterize an ideal friendship. Even so, romantic or sexual attraction between two friends can be a bonus—a sign of one's social worth—rather than a flaw.

The Rise of Opposite-Sex Friendship The question of whether men and women can be friends is relatively new, as is research into the dynamics of cross-sex friendships. (Scientific insights into homosexual same-sex friendship are even more scant, so this article will deal primarily with attraction between heterosexual friends of the opposite sex.)

Male-female friendship received its first big break from the feminist movement of the 1960s, which placed men and women on more equal ground in social and work situations. In addition to creating more opportunities for the sexes to interact, the changing social order made men and women more compatible as friends. We overwhelmingly choose friends who resemble us in attitudes and behaviors. It follows that when women and men occupied different and unequal spheres of life, they had less in common and thus were less likely to be close pals.

In the half a century since those social changes set in, opposite-sex friendships have become increasingly common. In 2002, for example, American Demographics magazine found that at the time of their survey, 18- to 24-year-olds were nearly four times as likely as people older than 55 to have a best friend of the opposite sex. More recent research also documents the historical novelty of male-female friendships. In a 2012 study psychologist April Bleske-Rechek of the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire asked college students how many of them had friends of the opposite sex—nearly all did. Compare that with what sociologist Rebecca G. Adams of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro found in 1985, when she asked 70 female senior citizens the same question: fewer than 4 percent of their friends were male.

Certain types of men and women are more likely to have more cross-sex friends. In a 2003 study Heidi Reeder, a communications professor at Boise State University, found that “feminine” men and “masculine” women (as measured by the Bem Sex Role Inventory) had a significantly higher proportion of cross-sex friendships than did “masculine” men and “feminine” women. The inventory is based on traditional sex roles, wherein subjects describing themselves as very “warm” or “sensitive,” for example, would score as more “feminine” than those describing themselves as “aggressive” and “analytical.” The interpretation is simple: whatever our sex, we prefer friends who are just like us.

Justified Doubt of “Just Friends” With the data clearly indicating that male-female friendship is thriving, perhaps it is time to abandon the old trope that men and women can't be “just friends.” Yet the idea has persisted for the simple reason that attraction can cause boundaries to blur. Consider, for example, one rare high-profile opposite-sex friendship from the late 1940s, when the young, religious and Southern Flannery O'Connor met the older, Waspy Robert Lowell at a retreat in upstate New York. Lowell brought O'Connor around to literary parties in Manhattan, with his fiancée also in tow. As O'Connor reportedly once wrote to a friend about Lowell, “I feel almost too much about him to be able to get to the heart of it.… He is one of the people I love.”

Psychological research has also documented the ambiguity of many cross-sex friendships. In 2000 psychologist Walid Afifi, then at Pennsylvania State University, surveyed 315 college students and found that approximately half had engaged in sexual activity with an otherwise platonic friend. In a 2012 study Bleske-Rechek and her colleagues asked 88 pairs of opposite-sex college-age friends about their friendship. They also sent questionnaires probing the pros and cons of opposite-sex friendships to 107 people between the ages of 18 and 23 and to 322 adults aged 27 to 55. In general, the men reported feeling slightly more attracted to their female friends than vice versa. Across age groups, participants described the friendships as beneficial overall, although they—and women in particular—tended to consider attraction a cost. For young women and for both sexes in the sample of older subjects, more attraction to their closest friend was associated with feeling less satisfied with their romantic partner. Widespread press coverage trumpeted the implication that men and women cannot be platonic, even if they are not having sex. Yet it is important to note that friendships persisted in spite of romantic or sexual attraction—quite the opposite conclusion.

Attraction is the basis of all friendship, and the carnal variety is common but not ubiquitous. Reeder analyzed hundreds of interview transcripts of people reflecting on their closest friend of the other gender and identified four types of attraction among the individuals. Almost all respondents reported feeling “friendship attraction,” that emotional resonance that Dan and Kate experienced once they shared their family histories. Only 14 percent reported “current romantic attraction,” defined as the desire to become a couple, although almost half said they had felt it earlier in the friendship. One third felt “subjective physical/sexual attraction,” which is a physical urge without a yearning for a serious partnership, and just more than 50 percent reported “objective physical/sexual attraction,” meaning they could see why others found their friend attractive even if they were not thus charmed. In short, the odds are pretty good that an opposite-sex friend did, or does, feel some pull toward the prurient.

The Myth of Pure Friendship With attraction abundant, the question becomes: So what? Skeptics of male-female friendship argue that if one person in the pair wants romance, the friendship is not truly platonic. With emotional skullduggery afoot, a pal's trustworthiness and dependability are thrown into question. Yet this argument oversimplifies the nature of friendship.

First, friends regularly factor into mating goals. Peers can introduce us to a potential partner, help evaluate who is a good match and instruct us in the social nuances that support romantic overtures. “Evolved mating strategies are operating in the background of any relationship,” Bleske-Rechek says. “But that doesn't mean we can't have constructive friendships with people we can count on.”

Some might argue that currying favor with an opposite-sex pal in the hope of kindling a physical relationship is not in keeping with the tenets of friendship. Yet this kind of behavior is common among companions. Without even noticing it, people routinely adjust their behavior to manipulate how their nearest and dearest feel about them. You might become more diligent about doing the dishes to maintain a peaceful environment at home. Or you might spend extra time composing a witty e-mail to a same-sex friend because you want to preserve that person's respect and admiration. “The idea that there is ‘pure’ friendship on one hand and friendship with an ulterior motive on the other is false and silly,” Bleske-Rechek says.

Indeed, the bulk of our friendships are imperfect in one way or another. About half of a person's social network is typically made up of ambivalent ties, according to work published in 2009 by psychologists Julianne Holt-Lunstad of Brigham Young University and Bert Uchino of the University of Utah. These are people we are reluctant to give up but who can be unpredictable or irritating. Such friendships extract a physical toll, as the researchers learned after having 107 study participants wear blood pressure monitors. When the subjects interacted with ambivalent friends, their blood pressure spiked higher than when they were with people whom they flat out did not like. Friendships come in many forms, and only a few of them live up to the ideal of selfless, supportive confidantes.

Dealing with Challenges The stress and uncertainty that romantic attraction brings to burgeoning friendships are not altogether different from the stress and uncertainty of any developing relationship, points out Geoffrey Greif, a professor of social work at the University of Maryland. “When you're beginning a same-sex friendship, you have to evaluate: ‘How am I going to pursue him? If I invite him to watch the Super Bowl and he says no, do I invite him to a movie some other time?’ You're always trying to gauge the other person's interest.” As to whether or not one should confess a desire for a romantic relationship with a friend, Greif recommends asking yourself if you will be unhappy a few years down the road should the person settle down with someone else.

To study the repercussions of such a baring of the soul, Reeder looked at the aftermath of friends' bold (but unsuccessful) disclosures of their secret passion. In friendships that survived the awkward conversation, both people tended to reaffirm the importance of their bond, acknowledge that the disclosure was acceptable, tone down any flirtatious behavior or innuendo, and resume their earlier contact patterns. The friend who demurred also acknowledged that the confessor's assumptions about the relationship's potential were justified, after which the confessor dropped the topic. Down the line, both pals openly discussed new prospective romantic partners.

In doomed friendships, the confessor complained and acted bothered when the friend did not agree to shift into romance and avoided contact with the object of their affection. The rejecter dangled false hope (“It's just that I'm with someone else right now”) and told other friends about the episode.

After Dan moved to New York, “we were hanging out as friends, and Dan was being flirtatious. He's so charming and funny,” Kate recalls. One night Dan went to Kate's apartment for dinner, a romantic setting that brought the question of dating into stark relief. “One little kiss happened,” Dan recalls, “and it felt like kissing my sister.”

“Part of the awkwardness,” Kate says, “was [me thinking] ‘I like this guy so much.’ We are never going to work out romantically—I can't even explain why—but we are destined to be really good friends. I felt so certain about that.”

Later, when Dan got married, the two friends learned to adjust to new boundaries. They pulled back on the number of hours they spent on the phone together, and Kate realized she could not lean on him as much for emotional support. “I started to develop some of my other friendships more,” she says. Dan's wife took on the role of his primary confidante, and he became more mindful that his outings with friends not eclipse their time together at home. As for Kate's potential threat as an attractive female: “My wife never expressed discomfort,” he notes, “because I think she realized, just from being around us, that it was platonic and that it was a nourishing friendship. But I had to adjust to the change, too.”

Friends with Many Benefits The good news is that most cross-sex friendships survive the pangs of romantic tension. Potential awkwardness aside, having a friend who is attracted to you can be beneficial. “Anytime someone expresses interest in you,” Reeder says, “they are affirming your worth in the social world.” She speculates that partners in a stagnant romantic relationship might feel empowered by the admiration of an opposite-sex friend.

Indeed, these friendships offer a few unique benefits beyond the standard assets of having a buddy. Men and women both report turning to opposite-sex pals to glean insights into how the other gender thinks. Dan, for example, describes how he often hears Kate's voice in his head as he contemplates relationship issues and dealings with women in general: “It's a necessary counterbalance to my male brain.”

Advice regarding a love interest might be the key dividend in one kind of cross-sex friendship: those between gay men and straight women. A 2013 study found that straight women are more likely to heed mating counsel from a gay man than from other sources, and gay men are likewise more inclined to trust advice from straight women than from straight men or lesbians. Unlike other alliances, friends who cross both sex and sexual orientation neither compete for mates nor weather the turbulence of unrequited desire. As a result, this bond has the potential to foster more trust than other ties, especially when it comes to unbiased dating insights.

More generally, strong friendships of any stripe are a tremendous boon to physical and mental physical health. To wit: Holt-Lunstad conducted a meta-analysis (a quantitative review of numerous studies) and concluded that having few friends is the mortality risk equivalent of smoking 15 cigarettes a day. People with a close friend at work are more productive and more innovative and have more fun than those without one. Couples, too, benefit when both partners have opposite-sex friends. Those who have a larger percentage of shared friends, as opposed to individual friends, tend to have happier and longer-lasting relationships. Strong social connections, in fact, are the biggest predictor of happiness in general.

Given the importance of social support to a healthy mind and body, it is unwise to kick half of the population out of your pool of potential friends. “Kate has made me less selfish,” Dan says. “Between us there's a sense of acceptance of the other person's neuroses, flaws—and even enjoyment of them. I take great comfort in a relationship that has stability even though it ebbs and flows in intensity.”

“Dan has influenced me—his work ethic has been inspiring, how seriously he takes his work. And I thrive on his sense of humor,” Kate says. “He's a friend I can completely trust. What a rare feeling that is, to be able to say anything to someone, without feeling censored.” Their decade-plus friendship, she says, “feels like one ongoing conversation.”

Kate and Dan have reached the highest levels of friendship, where life's great rewards—love, pleasure, and the ability to grow and learn—abound. They exemplify Aristotle's view on the best kind of friends. As described by philosopher Massimo Pigliucci of the City University of New York in his book Answers for Aristotle, such friends “hold a mirror up to each other; through that mirror they can see each other in ways that would not otherwise be accessible to them.” Whether the person holding the mirror is male or female hardly matters.

Carlin Flora is a freelance writer and author of Friendfluence: The Surprising Ways Friends Make Us Who We Are (Doubleday, 2013).