Essay Chats

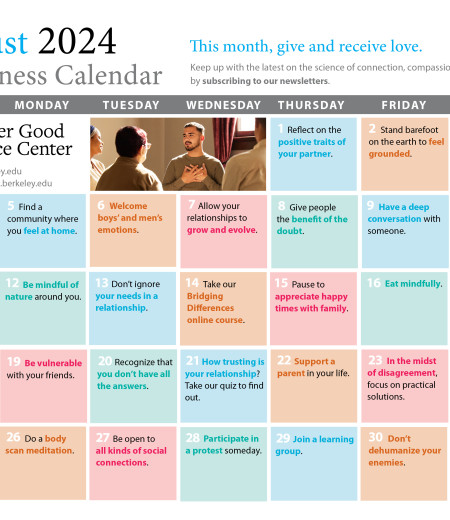

Learning And Growing Together Essay

Table of Contents

Introduction

Have you heard the saying, “Two heads are better than one”? This statement emphasizes that working together and sharing knowledge can lead to greater success and better outcomes. This concept is known as learning and growing together, and it is essential for personal and professional development. This Learning And Growing Together Essay will explore the benefits of learning and growing together, strategies for implementing this mindset, and examples of successful collaboration.

Here are the benefits of learning and growing together:

Collaboration and Teamwork

One of the main benefits of learning and growing together is the ability to collaborate and work as a team. Individuals can combine their unique strengths and skills to achieve a common goal when working together. For example, in a group project, one person may be good at research, while another may be skilled at graphic design. They can create a high-quality project showcasing their research and design skills by working together.

Improved Communication Skills

Learning and growing together also help individuals develop better communication skills. By practicing effective communication, individuals can avoid misunderstandings and work more efficiently. When working with others, expressing ideas clearly and listening to others’ perspectives is essential. In addition, good communication skills are important in personal and professional relationships.

Increased Creativity and Innovation

Another benefit of learning and growing together is the ability to generate new and innovative ideas. When individuals work alone, they may become stuck in their thought patterns and ideas. Working with others allows them to brainstorm and share ideas they may have yet to consider. This can lead to greater creativity and innovation, leading to better problem-solving.

Greater Accountability and Responsibility

Learning and growing together also promote greater accountability and responsibility. When individuals work alone, they may be tempted to procrastinate or take shortcuts. However, when working in a group, they are accountable to others and must take responsibility for their actions. This promotes a greater sense of responsibility and can lead to better work ethics.

Enhanced Problem-Solving Abilities

Finally, learning and growing together can enhance problem-solving abilities. When individuals work together, they can approach problems from different perspectives and develop more effective solutions. This is because everyone brings their own unique experiences and knowledge to the table, which can lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the problem.

Essay on Learning And Growing Together

Here are the strategies for learning and growing together:

Regular Check-Ins and Feedback Sessions

One strategy for learning and growing together is regular check-ins and feedback sessions. This can be done in a personal or professional setting. For example, in a classroom setting, students can work in pairs or small groups and have regular check-ins to discuss their progress and provide feedback. This helps individuals stay on track and ensures everyone is on the same page.

Sharing Knowledge and Skills

Another strategy for learning and growing together is to share knowledge and skills. This can be done by teaching others or by learning from others. For example, in a workplace, employees can attend training sessions to learn new skills or teach others their skills. This helps everyone improve their abilities and ensures the organization has a well-rounded and knowledgeable staff.

Participating in Group Training or Workshops

Participating in group training or workshops is also a great way to learn and grow together. These events allow individuals to learn new skills, share ideas, and network. For example, a group of students may attend a writing workshop to improve their writing skills. They can share ideas and learn from one another by attending this workshop together.

Encouraging Diversity and Inclusivity

Another strategy for learning and growing together is to encourage diversity and inclusivity. This means that individuals should embrace different perspectives, experiences, and backgrounds. By doing so, they can learn from one another and better understand the world around them. This can lead to more effective problem-solving and decision-making and a more positive and inclusive environment.

Setting Goals and Working Towards Them as a Team

Finally, setting goals and working towards them as a team is another effective strategy for learning and growing together. This helps individuals stay focused and motivated, ensuring everyone works towards a common goal. For example, a group of coworkers may set a goal to increase sales by a certain percentage. By working towards this goal together, they can hold each other accountable and ensure everyone is doing their part.

Examples of Successful Learning and Growing Together (Essay)

There are many examples of successful collaboration and learning, and growing together. One such example was the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969. The mission involved a team of scientists, engineers, and astronauts who worked together to accomplish a historic feat. Each person brought their unique skills and knowledge to the project, and by working together, they overcame challenges and achieved their goal.

Scientists worldwide worked together to create an effective vaccine against the virus. By sharing their knowledge and collaborating, they were able to develop a vaccine in record time. Another example of successful collaboration is the development of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Challenges and Potential Roadblocks

While learning and growing together can be incredibly beneficial, challenges and potential roadblocks can arise. One common challenge is the need for more communication. When individuals are not communicating effectively, misunderstandings can occur, leading to conflict and delays in the project.

Another challenge is the need for more trust. When individuals do not trust one another, they may hesitate to share their ideas or work together. This can lead to poor collaboration and hinder the project’s progress.

Finally, lacking diversity and inclusivity can also be a potential roadblock. When individuals do not embrace different perspectives and experiences, they may miss out on important insights and ideas. This can lead to a lack of creativity and innovation, hindering the project’s success.

The Learning and growing together Essay concludes that learning and growing together is essential for personal and professional development. By collaborating, sharing knowledge and skills, and working towards common goals, individuals can achieve greater success and better outcomes. While challenges can arise, these can be overcome with effective communication, trust, and a commitment to diversity and inclusivity. So, whether you are working on a group project in school or collaborating with coworkers in the workplace, remember the benefits of learning and growing together and embrace the power of teamwork.

Checkout these posts:

Short essay on service to man is service to God

God the only friend Essay

Cut your coat according to your cloth Essay

What is learning and growing together?

Learning and growing together is a collaborative process where individuals work together to gain knowledge, skills, and experiences. It involves a shared commitment to personal and collective growth, where everyone involved contributes to each other’s learning and development.

Why learning and growing together is important?

Learning and growing together is important because it fosters a sense of community and collaboration, which can lead to improved outcomes for everyone involved. It creates a supportive environment where individuals can learn from each other’s strengths and weaknesses and work together to overcome challenges. Additionally, it promotes a growth mindset where individuals are open to feedback and continuously strive to improve themselves and their collective goals.

What is the power of learning together?

The power of learning together lies in the collective knowledge and experiences of the group. When individuals come together to learn and grow, they bring unique perspectives and insights that can broaden everyone’s understanding of a subject. Additionally, the group can provide a supportive environment encouraging risk-taking and experimentation, leading to innovative solutions and increased creativity.

Which is a process of learning and growth?

The process of learning and growth involves several key steps. First, individuals must have a growth mindset and be open to feedback and continuous learning. They must also be willing to take risks and experiment with new ideas. Next, individuals must actively seek learning opportunities and grow through formal education or informal experiences. Finally, individuals must reflect on their experiences and use their newfound knowledge and skills to improve themselves and their community.

What is the learning together model?

The learning together model is a collaborative approach to learning and growth that emphasizes the importance of community and shared experiences. It involves individuals working together towards a common goal, each contributing unique skills and perspectives. The learning together model encourages active participation and engagement, with individuals taking responsibility for their learning while also supporting the learning of others. This model can be applied in various settings, from classrooms to workplaces to community organizations.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Educationalist

Growing together: What's the key to a successful learning community?

The educationalist. by alexandra mihai.

Welcome to a new issue of “The Educationalist”! As I am settling into my new adventure at the Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning at Yale , I am trying to make the most of these first weeks, full of new ideas and reflections. After all, nothing compares to being in a new place- it gives you the chance to practice “beginner’s mind”, to challenge your assumptions and open your mind to new ways of doing things. One of the thing I noticed already after a few days is that faculty learning communities feature much more prominently among faculty development activities here than at the European universities I am familiar with. So I decided to dedicate some time to learning more about different approaches of community building and facilitation. This newsletter is only the starting point, bringing up some initial thoughts and questions I have, as well as some resources for further reading. If you have experience facilitating faculty learning communities, I would be very happy to hear from you and start a conversation!

What is a learning community?

Moving from knowledge transmission- be it pedagogical, technological or both- towards facilitating learning communities has been an important topic on the faculty development agenda for quite a while now. Nothing new here. Professional learning communities have been, at least in theory, one staff development avenue used with various degrees of success in different contexts and at different levels of the education system. They are based on the idea of creating a space for reflective practitioners to exchange and crowdsource ideas and support each other in their practice . This is my own (distilled) definition, but you can find more nuanced definitions and interpretations in some of the resources listed below.

While the concept itself is very generous and inviting, and it certainly feels suitable to the world of Higher Education, creating and maintaining learning communities is more challenging than it may sound . To begin with, it is not a straightforward, well-structured faculty development activity such as, for instance, a workshop, or even a consultation. People need to commit more time to it, which is always a tricky thing with so many competing demands on our limited time. Moreover, the immediate outcome may be less tangible than in the case of a targeted workshop. Arguably, the value of a learning community increases proportionately with the effort and commitment participants put into it. So does the perceived value. You get it, it’s a vicious circle.

So how can we start to turn it into a virtuous circle? In my first three weeks at the Poorvu Center I already had the chance to observe a few instances of learning communities. While the number of participants was not very high, the quality and depth of discussions was. So I started thinking about what it takes to nurture a learning community so that it becomes a space where faculty look forward to coming and exchanging with peers.

Faculty learning communities can be created within departments (with a more homogeneous disciplinary composition) but also across disciplines , focusing on specific topics, like assessment and feedback, use of technology, etc. Both approaches can offer benefits and in fact communities can perfectly run in parallel and cross-pollinate. The key is to plant the seeds for a culture of exchange and collaboration in teaching and learning . Having functioning learning communities, however small at first, is a valuable testimony of a cultural change. It’s something we can work with.

I wrote more about the benefits of cultivating a dialogue about our teaching practice, including some examples of how to do it here . Sanna Eronen also wrote on the importance of peer support as a tool for faculty development here , giving some great examples and tips based on her practice.

There are many good reasons why facilitating faculty learning communities is an important aspect of educational development. Here are the ones I find most important- again distilled from my perspective:

Safe space : creating a space where faculty can “come as they are”, where they can afford to be vulnerable, imperfect and share their experiences with peers. This is the most difficult thing to achieve, also the most valuable. It takes time, patience, perseverance and a gentle welcoming attitude.

Validation : providing opportunities for faculty to get their teaching practice validated: by peers, by educational developers and ultimately by the broader institutional community. We can act as cheerleaders- this role is almost as important as providing direct support.

Crowdsourcing ideas: a learning community is essentially a space where more minds come together and think through their challenges. The results are rich, sometimes surprising and definitely provide lots of food for thought.

Accountability: making changes in our practice is hard as it is. Doing it alone can be really daunting. A community can provide chances to partner up and work through changes together. Share notes. Keep each other accountable in a gentle, collegial way.

Facilitating a learning community

Creating a learning community, facilitating it and nurturing its development and growth takes commitment . Individual commitment and institutional commitment. It takes time and it requires resources (which might not be self-evident, but think about it for a minute!). Building and especially maintaining a community implies a cultural shift . And these don’t just happen overnight. I heard many colleagues at various institutions who tried to establish various formats of learning communities, and failed. No matter how passionate they were about it. It happened to me too. And all too often we give up on this informal, light touch approach that seems ever more elusive and put our efforts into highly structured programmes like workshops and certificates.

Still, there is nothing that prevents these two paths from running in parallel, and cross each other every now and then. But we need to acknowledge that successfully building a learning community requires a specific set of skills . Here is how I’d summarise it:

Reach out : proactively going to different departments/ faculties and talking to people, finding what their needs are and planting the seeds for a culture of exchange;

Connect : creating networks that bring together people with similar interests, connecting the dots, bringing people in the same room (physically or virtually);

Listen : active listening plays a key role; taking yourself out of the equation so that you can help create an atmosphere of trust;

Facilitate : conversations can sometimes be difficult; being prepared to manage those moments, knowing when to step in and when to take a step back (it’s an art);

Curate : creating a repository of resources, which is always “work in progress”; encouraging co-creating and co-curation; this is the lasting legacy of a community.

In terms of space and modality , both virtual and physical spaces work well, the key is keeping a certain degree of flexibility and technology can help with this. For instance, the curation element, but also part of the networking element can take place in the virtual environment. However, the social aspect can be enhanced by the presence of coffee and cake :)

How about engagement ? We can start with the "usual suspects", people who come to us often and are enthusiastic about their teaching. Then we could try adding a "bring a friend" policy. In time, the community hopefully grows, at its own pace. Every new member is a small win. Again, we’re talking about a marathon here, not a sprint.

Last but not least, trying to build learning communities right now is a very good way to support Faculty reconnect with peers after a (too) long time of working and teaching remotely. Creating a shared space. A safe space. A sandbox. Centres for Teaching and Learning can initiate and facilitate these communities, but ideally, given time, the spirit will spread beyond their boundaries.

Faculty Learning Communities: Five Skills Every Facilitator Should Capture - a collection of useful tips for those of us aiming to build and facilitate learning communities;

Sustaining pedagogical change via faculty learning community , by Teresa L. Tinnell, Patricia A. S. Ralston, Thomas R. Tretter and Mary E. Mills- article offering interesting insights on the relation between faculty learning communities and lasting pedagogical change;

Faculty Learning Communities: A Model for Supporting Curriculum Changes in Higher Education , by Marion Engin and Fairlie Atkinson- an article reflecting on the benefits and limitations of a faculty learning community;

Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature , by Louise Stoll, Ray Bolam, Agnes McMahon, Mike Wallace and Sally Thomas- A broad overview of professional learning communities as a tool for capacity building;

Community of Practice Design Guide: A Step-by-Step Guide for Designing & Cultivating Communities of Practice in Higher Education - provides a structure to help clarify the most important design elements that go into defining, designing, launching, and growing CoPs- both online and face-to-face;

Practices of Professional Learning Communities , by Markku Antinluoma, Liisa Ilomäki and Auli Toom- an article which investigates practices of leadership, culture, teacher collaboration, professional learning, and development;

Faculty Learning Communities: Making the Connection, Virtually - some thoughts on creating and maintaining virtual learning communities (written before Covid but definitely making some relevant points for the current context);

Can online learning communities achieve the goals of traditional professional learning communities? What the literature says - a literature review on online and hybrid professional learning communities.

Letter to Faculty

This week I had the chance to attend a very inspiring workshop on alternative assessment methods with Jesse Stommel . During a 4 minute writing exercise, he had us write a “letter to students” (or to faculty, for those of us in faculty development) in which we acknowledge our values, what success looks like for us and how we try to show we care. I found it a great exercise and I am sharing what I wrote not because I think it’s great, but because it captures the raw essence of my faculty development approach (also closely linked to the idea of learning community) and I hope it may serve as inspiration for some of you:

This space is your space. A space for learning. For trying new things. For failing. And again, for learning. I value your presence. I value your questions. Keep them coming. I can’t promise I have all the answers you need but I commit to do my best to support you in finding your answers. And in asking ever more questions.

Your success is not going to be measured only in student evaluations. Your value as teachers goes far beyond that. If you tried something and reflected on it. If you changed a small part of your practice and see the benefits. If you had a student coming and telling you that you did a good job. This is success .

Learn from each other. Talk to each other. Put your experiences together. This collective experience will value more than the sum of its parts. But don’t forget to take care of yourself. Be there for yourself so you can be there for your students.

What’s new @ The Educationalist?

It is my pleasure to invite you to check out three new stories , part of the “Around the world” faculty development series:

How faculty development can contribute to the well-being of academics: Reflections from practice , by Dr. Inken Gast , Maastricht University, The Netherlands, where she shares some useful tips about how we as faculty developers can make a positive impact on the well-being of academics;

“Around the world” podcast, episode 6: Digital competencies and internationalisation , with Chahira Nouira , University of Göttingen, Germany, where she talks about how the good use of virtual environments, together with digital skills development can benefit interdisciplinary collaboration and broaden the geographical reach;

“Around the world” podcast, episode 7: Institutional support for the use of educational technology , with Dr. Jenae Cohn , California State University, Sacramento, USA, where we discuss about her institutional role as a translator and bridge builder between different actors (Faculty, staff, students, IT, etc) and some lessons learned during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Ready for more?

What Is Learning? Essay about Learning Importance

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

What Is learning? 👨🎓️ Why is learning important? Find the answers here! 🔤 This essay on learning describes its outcomes and importance in one’s life.

Introduction

- The Key Concepts

Learning is a continuous process that involves the transformation of information and experience into abilities and knowledge. Learning, according to me, is a two way process that involves the learner and the educator leading to knowledge acquisition as well as capability.

It informs my educational sector by making sure that both the students and the teacher participate during the learning process to make it more real and enjoyable so that the learners can clearly understand. There are many and different learning concepts held by students and ways in which the different views affect teaching and learning.

What Is Learning? The Key Concepts

One of the learning concept held by students is, presentation of learning material that is precise. This means that any material that is meant for learning should be very clear put in a language that the learners comprehend (Blackman & Benson 2003). The material should also be detailed with many examples that are relevant to the prior knowledge of the learner.

This means that the learner must have pertinent prior knowledge. This can be obtained by the teacher explaining new ideas and words that are to be encountered in a certain field or topic that might take more consecutive lessons. Different examples assist the students in approaching ideas in many perspectives.

The learner is able to get similarities from the many examples given thus leading to a better understanding of a concept since the ideas are related and linked.

Secondly, new meanings should be incorporated into the students’ prior knowledge, instead of remembering only the definitions or procedures. Therefore, to promote expressive learning, instructional methods that relate new information to the learner’s prior knowledge should be used.

Moreover, significant learning involves the use of evaluation methods that inspire learners to relate their existing knowledge with new ideas. For the students to comprehend complex ideas, they must be combined with the simple ideas they know.

Teaching becomes very easy when a lesson starts with simple concepts that the students are familiar with. The students should start by understanding what they know so that they can use the ideas in comprehending complex concepts. This makes learning smooth and easy for both the learner and the educator (Chermak& Weiss 1999).

Thirdly, acquisition of the basic concepts is very essential for the student to understand the threshold concepts. This is because; the basic concepts act as a foundation in learning a certain topic or procedure. So, the basic concepts must be comprehended first before proceeding to the incorporation of the threshold concepts.

This makes the student to have a clear understanding of each stage due to the possession of initial knowledge (Felder &Brent 1996). A deeper foundation of the study may also be achieved through getting the differences between various concepts clearly and by knowing the necessary as well as the unnecessary aspects. Basic concepts are normally taught in the lower classes of each level.

They include defining terms in each discipline. These terms aid in teaching in all the levels because they act as a foundation. The stage of acquiring the basics determines the students’ success in the rest of their studies.

This is because lack of basics leads to failure since the students can not understand the rest of the context in that discipline, which depends mostly on the basics. For learning to become effective to the students, the basics must be well understood as well as their applications.

Learning by use of models to explain certain procedures or ideas in a certain discipline is also another learning concept held by students. Models are helpful in explaining complex procedures and they assist the students in understanding better (Blackman & Benson 2003).

For instance, in economics, there are many models that are used by the students so that they can comprehend the essential interrelationships in that discipline. A model known as comparative static is used by the students who do economics to understand how equilibrium is used in economic reason as well as the forces that bring back equilibrium after it has been moved.

The students must know the importance of using such kind of models, the main aspect in the model and its relationship with the visual representation. A model is one of the important devices that must be used by a learner to acquire knowledge. They are mainly presented in a diagram form using symbols or arrows.

It simplifies teaching especially to the slow learners who get the concept slowly but clearly. It is the easiest and most effective method of learning complex procedures or directions. Most models are in form of flowcharts.

Learners should get used to learning incomplete ideas so that they can make more complete ideas available to them and enjoy going ahead. This is because, in the process of acquiring the threshold concepts, the prior knowledge acquired previously might be transformed.

So, the students must be ready to admit that every stage in the learning process they get an understanding that is temporary. This problem intensifies when the understanding of an idea acquired currently changes the understanding of an idea that had been taught previously.

This leads to confusion that can make the weak students lose hope. That is why the teacher should always state clear similarities as well as differences of various concepts. On the other hand, the student should be able to compare different concepts and stating their similarities as well as differences (Watkins & Regmy 1992).

The student should also be careful when dealing with concepts that seem similar and must always be attentive to get the first hand information from the teacher. Teaching and learning becomes very hard when learners do not concentrate by paying attention to what the teacher is explaining. For the serious students, learning becomes enjoyable and they do not get confused.

According to Chemkar and Weiss (1999), learners must not just sit down and listen, but they must involve themselves in some other activities such as reading, writing, discussing or solving problems. Basically, they must be very active and concentrate on what they are doing. These techniques are very essential because they have a great impact to the learners.

Students always support learning that is active than the traditional lecture methods because they master the content well and aids in the development of most skills such as writing and reading. So methods that enhance active learning motivate the learners since they also get more information from their fellow learners through discussions.

Students engage themselves in discussion groups or class presentations to break the monotony of lecture method of learning. Learning is a two way process and so both the teacher and the student must be involved.

Active learning removes boredom in the class and the students get so much involved thus improving understanding. This arouses the mind of the student leading to more concentration. During a lecture, the student should write down some of the important points that can later be expounded on.

Involvement in challenging tasks by the learners is so much important. The task should not be very difficult but rather it should just be slightly above the learner’s level of mastery. This makes the learner to get motivated and instills confidence. It leads to success of the learner due to the self confidence that aids in problem solving.

For instance, when a learner tackles a question that deemed hard and gets the answer correct, it becomes the best kind of encouragement ever. The learner gets the confidence that he can make it and this motivates him to achieve even more.

This kind of encouragement mostly occurs to the quick learners because the slow learners fail in most cases. This makes the slow learners fear tackling many problems. So, the concept might not apply to all the learners but for the slow learners who are determined, they can always seek for help incase of such a problem.

Moreover, another concept held by students is repetition because, the most essential factor in learning is efficient time in a task. For a student to study well he or she should consider repetition, that is, looking at the same material over and over again.

For instance, before a teacher comes for the lesson, the student can review notes and then review the same notes after the teacher gets out of class. So, the student reviews the notes many times thus improving the understanding level (Felder & Brent 1996). This simplifies revising for an exam because the student does not need to cram for it.

Reviewing the same material makes teaching very easy since the teacher does not need to go back to the previous material and start explaining again. It becomes very hard for those students who do not review their work at all because they do not understand the teacher well and are faced by a hard time when preparing for examinations.

Basically, learning requires quite enough time so that it can be effective. It also becomes a very big problem for those who do not sacrifice their time in reviews.

Acquisition of the main points improves understanding of the material to the student. Everything that is learnt or taught may not be of importance. Therefore, the student must be very keen to identify the main points when learning. These points should be written down or underlined because they become useful when reviewing notes before doing an exam. It helps in saving time and leads to success.

For those students who do not pay attention, it becomes very difficult for them to highlight the main points. They read for the sake of it and make the teacher undergo a very hard time during teaching. To overcome this problem, the students must be taught how to study so that learning can be effective.

Cooperative learning is also another concept held by the students. It is more detailed than a group work because when used properly, it leads to remarkable results. This is very encouraging in teaching and the learning environment as well.

The students should not work with their friends so that learning can be productive, instead every group should have at least one top level student who can assist the weak students. The groups assist them in achieving academic as well as social abilities due to the interaction. This learning concept benefits the students more because, a fellow student can explain a concept in a better way than how the teacher can explain in class.

Assignments are then given to these groups through a selected group leader (Felder& Brent 1996). Every member must be active in contributing ideas and respect of one’s ideas is necessary. It becomes very easy for the teacher to mark such kind of assignments since they are fewer than marking for each individual.

Learning becomes enjoyable because every student is given a chance to express his or her ideas freely and in a constructive manner. Teaching is also easier because the students encounter very many new ideas during the discussions. Some students deem it as time wastage but it is necessary in every discipline.

Every group member should be given a chance to become the group’s facilitator whose work is to distribute and collect assignments. Dormant students are forced to become active because every group member must contribute his or her points. Cooperative learning is a concept that requires proper planning and organization.

Completion of assignments is another student held learning concept. Its main aim is to assist the student in knowing whether the main concepts in a certain topic were understood. This acts as a kind of self evaluation to the student and also assists the teacher to know whether the students understood a certain topic. The assignments must be submitted to the respective teacher for marking.

Those students who are focused follow the teacher after the assignments have been marked for clarification purposes. This enhances learning and the student understands better. Many students differ with this idea because they do not like relating with the teacher (Marton &Beaty 1993). This leads to very poor grades since communication is a very essential factor in learning.

Teaching becomes easier and enjoyable when there is a student- teacher relationship. Assignment corrections are necessary to both the student and the teacher since the student comprehends the right method of solving a certain problem that he or she could not before.

Lazy students who do not do corrections make teaching hard for the teacher because they make the other students to lag behind. Learning may also become ineffective for them due to low levels of understanding.

Acquisition of facts is still another student held concept that aims at understanding reality. Students capture the essential facts so that they can understand how they suit in another context. Many students fail to obtain the facts because they think that they can get everything taught in class or read from books.

When studying, the student must clearly understand the topic so that he or she can develop a theme. This helps in making short notes by eliminating unnecessary information. So, the facts must always be identified and well understood in order to apply them where necessary. Teaching becomes easier when the facts are well comprehended by the students because it enhances effective learning.

Effective learning occurs when a student possesses strong emotions. A strong memory that lasts for long is linked with the emotional condition of the learner. This means that the learners will always remember well when learning is incorporated with strong emotions. Emotions develop when the students have a positive attitude towards learning (Marton& Beaty 1993).

This is because they will find learning enjoyable and exciting unlike those with a negative attitude who will find learning boring and of no use to them. Emotions affect teaching since a teacher will like to teach those students with a positive attitude towards what he is teaching rather than those with a negative attitude.

The positive attitude leads to effective learning because the students get interested in what they are learning and eventually leads to success. Learning does not become effective where students portray a negative attitude since they are not interested thus leading to failure.

Furthermore, learning through hearing is another student held concept. This concept enables them to understand what they hear thus calling for more attention and concentration. They prefer instructions that are given orally and are very keen but they also participate by speaking. Teaching becomes very enjoyable since the students contribute a lot through talking and interviewing.

Learning occurs effectively because the students involve themselves in oral reading as well as listening to recorded information. In this concept, learning is mostly enhanced by debating, presenting reports orally and interviewing people. Those students who do not prefer this concept as a method of learning do not involve themselves in debates or oral discussions but use other learning concepts.

Learners may also use the concept of seeing to understand better. This makes them remember what they saw and most of them prefer using written materials (Van Rosum & Schenk 1984). Unlike the auditory learners who grasp the concept through hearing, visual learners understand better by seeing.

They use their sight to learn and do it quietly. They prefer watching things like videos and learn from what they see. Learning occurs effectively since the memory is usually connected with visual images. Teaching becomes very easy when visual images are incorporated. They include such things like pictures, objects, graphs.

A teacher can use charts during instruction thus improving the students’ understanding level or present a demonstration for the students to see. Diagrams are also necessary because most students learn through seeing.

Use of visual images makes learning to look real and the student gets the concept better than those who learn through imaginations. This concept makes the students to use text that has got many pictures, diagrams, graphics, maps and graphs.

In learning students may also use the tactile concept whereby they gain knowledge and skills through touching. They gain knowledge mostly through manipulative. Teaching becomes more effective when students are left to handle equipments for themselves for instance in a laboratory practical. Students tend to understand better because they are able to follow instructions (Watkins & Regmy 1992).

After applying this concept, the students are able to engage themselves in making perfect drawings, making models and following procedures to make something. Learning may not take place effectively to those students who do not like manipulating because it arouses the memory and the students comprehends the concept in a better way.

Learning through analysis is also another concept held by students because they are able to plan their work in an organized manner which is based on logic ideas only. It requires individual learning and effective learning occurs when information is given in steps. This makes the teacher to structure the lessons properly and the goals should be clear.

This method of organizing ideas makes learning to become effective thus leading to success and achievement of the objectives. Analysis improves understanding of concepts to the learners (Watkins & Regmy 1992). They also understand certain procedures used in various topics because they are sequential.

Teaching and learning becomes very hard for those students who do not know how to analyze their work. Such students learn in a haphazard way thus leading to failure.

If all the learning concepts held by students are incorporated, then remarkable results can be obtained. A lot information and knowledge can be obtained through learning as long as the learner uses the best concepts for learning. Learners are also different because there are those who understand better by seeing while others understand through listening or touching.

So, it is necessary for each learner to understand the best concept to use in order to improve the understanding level. For the slow learners, extra time should be taken while studying and explanations must be clear to avoid confusion. There are also those who follow written instructions better than those instructions that are given orally. Basically, learners are not the same and so require different techniques.

Reference List

Benson, A., & Blackman, D., 2003. Can research methods ever be interesting? Active Learning in Higher Education, Vol. 4, No. 1, 39-55.

Chermak, S., & Weiss, A., 1999. Activity-based learning of statistics: Using practical applications to improve students’ learning. Journal of Criminal Justice Education , Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 361-371.

Felder, R., & Brent, R., 1996. Navigating the bumpy road to student-centered instruction. College Teaching , Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 43-47.

Marton, F. & Beaty, E., 1993. Conceptions of learning. International Journal of Educational Research , Vol. 19, pp. 277-300.

Van Rossum, E., & Schenk, S., 1984. The relationship between learning conception, study strategy and learning outcome. British Journal of Educational Psychology , Vol. 54, No.1, pp. 73-85.

Watkins, D., & Regmy, M., 1992. How universal are student conceptions of learning? A Nepalese investigation. Psychologia , Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 101-110.

What Is Learning? FAQ

- Why Is Learning Important? Learning means gaining new knowledge, skills, and values, both in a group or on one’s own. It helps a person to develop, maintain their interest in life, and adapt to changes.

- Why Is Online Learning Good? Online learning has a number of advantages over traditional learning. First, it allows you to collaborate with top experts in your area of interest, no matter where you are located geographically. Secondly, it encourages independence and helps you develop time management skills. Last but not least, it saves time on transport.

- How to Overcome Challenges in Online Learning? The most challenging aspects of distant learning are the lack of face-to-face communication and the lack of feedback. The key to overcoming these challenges is effective communication with teachers and classmates through videoconferencing, email, and chats.

- The Benefits and Issues in Bilingual Education

- Benefits of Online College

- Apple’s iBook Using in Schools

- Students in School: Importance of Assessment Essay

- Instructional Plan in Writing for Learners With Disabilities

- Concept of Learning Geometry in School

- Distance Learning OL and Interactive Video in Higher Education

- Taxonomy of Learning Objectives

- Importance of social interaction to learning

- Comparing learning theories

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, May 2). What Is Learning? Essay about Learning Importance. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-learning-essay/

"What Is Learning? Essay about Learning Importance." IvyPanda , 2 May 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-learning-essay/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'What Is Learning? Essay about Learning Importance'. 2 May.

IvyPanda . 2019. "What Is Learning? Essay about Learning Importance." May 2, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-learning-essay/.

1. IvyPanda . "What Is Learning? Essay about Learning Importance." May 2, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-learning-essay/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "What Is Learning? Essay about Learning Importance." May 2, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-learning-essay/.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

8 Overcoming Challenges College Essay Examples

The purpose of the Overcoming Challenges essay is for schools to see how you might handle the difficulties of college. They want to know how you grow, evolve, and learn when you face adversity. For this topic, there are many clichés , such as getting a bad grade or losing a sports game, so be sure to steer clear of those and focus on a topic that’s unique to you. (See our full guide on the Overcoming Challenges Essay for more tips).

These overcoming challenges essay examples were all written by real students. Read through them to get a sense of what makes a strong essay. At the end, we’ll present the revision process for the first essay and share some resources for improving your essay.

Please note: Looking at examples of real essays students have submitted to colleges can be very beneficial to get inspiration for your essays. You should never copy or plagiarize from these examples when writing your own essays. Colleges can tell when an essay isn’t genuine and will not view students favorably if they plagiarized.

Essay 1: Becoming a Coach

“Advanced females ages 13 to 14 please proceed to staging with your coaches at this time.” Skittering around the room, eyes wide and pleading, I frantically explained my situation to nearby coaches. The seconds ticked away in my head; every polite refusal increased my desperation.

Despair weighed me down. I sank to my knees as a stream of competitors, coaches, and officials flowed around me. My dojang had no coach, and the tournament rules prohibited me from competing without one.

Although I wanted to remain strong, doubts began to cloud my mind. I could not help wondering: what was the point of perfecting my skills if I would never even compete? The other members of my team, who had found coaches minutes earlier, attempted to comfort me, but I barely heard their words. They couldn’t understand my despair at being left on the outside, and I never wanted them to understand.

Since my first lesson 12 years ago, the members of my dojang have become family. I have watched them grow up, finding my own happiness in theirs. Together, we have honed our kicks, blocks, and strikes. We have pushed one another to aim higher and become better martial artists. Although my dojang had searched for a reliable coach for years, we had not found one. When we attended competitions in the past, my teammates and I had always gotten lucky and found a sympathetic coach. Now, I knew this practice was unsustainable. It would devastate me to see the other members of my dojang in my situation, unable to compete and losing hope as a result. My dojang needed a coach, and I decided it was up to me to find one.

I first approached the adults in the dojang – both instructors and members’ parents. However, these attempts only reacquainted me with polite refusals. Everyone I asked told me they couldn’t devote multiple weekends per year to competitions. I soon realized that I would have become the coach myself.

At first, the inner workings of tournaments were a mystery to me. To prepare myself for success as a coach, I spent the next year as an official and took coaching classes on the side. I learned everything from motivational strategies to technical, behind-the-scenes components of Taekwondo competitions. Though I emerged with new knowledge and confidence in my capabilities, others did not share this faith.

Parents threw me disbelieving looks when they learned that their children’s coach was only a child herself. My self-confidence was my armor, deflecting their surly glances. Every armor is penetrable, however, and as the relentless barrage of doubts pounded my resilience, it began to wear down. I grew unsure of my own abilities.

Despite the attack, I refused to give up. When I saw the shining eyes of the youngest students preparing for their first competition, I knew I couldn’t let them down. To quit would be to set them up to be barred from competing like I was. The knowledge that I could solve my dojang’s longtime problem motivated me to overcome my apprehension.

Now that my dojang flourishes at competitions, the attacks on me have weakened, but not ended. I may never win the approval of every parent; at times, I am still tormented by doubts, but I find solace in the fact that members of my dojang now only worry about competing to the best of their abilities.

Now, as I arrive at a tournament with my students, I close my eyes and remember the past. I visualize the frantic search for a coach and the chaos amongst my teammates as we competed with one another to find coaches before the staging calls for our respective divisions. I open my eyes to the exact opposite scene. Lacking a coach hurt my ability to compete, but I am proud to know that no member of my dojang will have to face that problem again.

This essay begins with an in-the-moment narrative that really illustrates the chaos of looking for a coach last-minute. We feel the writer’s emotions, particularly their dejectedness, at not being able to compete.

Through this essay, we can see how gutsy and determined the student is in deciding to become a coach themselves. The writer shows us these characteristics through their actions, rather than explicitly telling us: To prepare myself for success as a coach, I spent the next year as an official and took coaching classes on the side.

One area of improvement of this essay would be the “attack” wording. The author likely uses this word as a metaphor for martial arts, but it feels too strong to describe the adults’ doubt of the student’s abilities as a coach, and can even be confusing at first.

Still, we see the student’s resilience as they are able to move past the disbelieving looks to help their team. The essay is kept real and vulnerable, however, as the writer admits having doubts: Every armor is penetrable, however, and as the relentless barrage of doubts pounded my resilience, it began to wear down. I grew unsure of my own abilities.

The essay comes full circle as the author recalls the frantic situations in seeking out a coach, but this is no longer a concern for them and their team. Overall, this essay is extremely effective in painting this student as mature, bold, and compassionate.

Essay 2: Starting a Fire

Was I no longer the beloved daughter of nature, whisperer of trees? Knee-high rubber boots, camouflage, bug spray—I wore the garb and perfume of a proud wild woman, yet there I was, hunched over the pathetic pile of stubborn sticks, utterly stumped, on the verge of tears. As a child, I had considered myself a kind of rustic princess, a cradler of spiders and centipedes, who was serenaded by mourning doves and chickadees, who could glide through tick-infested meadows and emerge Lyme-free. I knew the cracks of the earth like the scars on my own rough palms. Yet here I was, ten years later, incapable of performing the most fundamental outdoor task: I could not, for the life of me, start a fire.

Furiously I rubbed the twigs together—rubbed and rubbed until shreds of skin flaked from my fingers. No smoke. The twigs were too young, too sticky-green; I tossed them away with a shower of curses, and began tearing through the underbrush in search of a more flammable collection. My efforts were fruitless. Livid, I bit a rejected twig, determined to prove that the forest had spurned me, offering only young, wet bones that would never burn. But the wood cracked like carrots between my teeth—old, brittle, and bitter. Roaring and nursing my aching palms, I retreated to the tent, where I sulked and awaited the jeers of my family.

Rattling their empty worm cans and reeking of fat fish, my brother and cousins swaggered into the campsite. Immediately, they noticed the minor stick massacre by the fire pit and called to me, their deep voices already sharp with contempt.

“Where’s the fire, Princess Clara?” they taunted. “Having some trouble?” They prodded me with the ends of the chewed branches and, with a few effortless scrapes of wood on rock, sparked a red and roaring flame. My face burned long after I left the fire pit. The camp stank of salmon and shame.

In the tent, I pondered my failure. Was I so dainty? Was I that incapable? I thought of my hands, how calloused and capable they had been, how tender and smooth they had become. It had been years since I’d kneaded mud between my fingers; instead of scaling a white pine, I’d practiced scales on my piano, my hands softening into those of a musician—fleshy and sensitive. And I’d gotten glasses, having grown horrifically nearsighted; long nights of dim lighting and thick books had done this. I couldn’t remember the last time I had lain down on a hill, barefaced, and seen the stars without having to squint. Crawling along the edge of the tent, a spider confirmed my transformation—he disgusted me, and I felt an overwhelming urge to squash him.

Yet, I realized I hadn’t really changed—I had only shifted perspective. I still eagerly explored new worlds, but through poems and prose rather than pastures and puddles. I’d grown to prefer the boom of a bass over that of a bullfrog, learned to coax a different kind of fire from wood, having developed a burn for writing rhymes and scrawling hypotheses.

That night, I stayed up late with my journal and wrote about the spider I had decided not to kill. I had tolerated him just barely, only shrieking when he jumped—it helped to watch him decorate the corners of the tent with his delicate webs, knowing that he couldn’t start fires, either. When the night grew cold and the embers died, my words still smoked—my hands burned from all that scrawling—and even when I fell asleep, the ideas kept sparking—I was on fire, always on fire.

This essay is an excellent example because the writer turns an everyday challenge—starting a fire—into an exploration of her identity. The writer was once “a kind of rustic princess, a cradler of spiders and centipedes,” but has since traded her love of the outdoors for a love of music, writing, and reading.

The story begins in media res , or in the middle of the action, allowing readers to feel as if we’re there with the writer. One of the essay’s biggest strengths is its use of imagery. We can easily visualize the writer’s childhood and the present day. For instance, she states that she “rubbed and rubbed [the twigs] until shreds of skin flaked from my fingers.”

The writing has an extremely literary quality, particularly with its wordplay. The writer reappropriates words and meanings, and even appeals to the senses: “My face burned long after I left the fire pit. The camp stank of salmon and shame.” She later uses a parallelism to cleverly juxtapose her changed interests: “instead of scaling a white pine, I’d practiced scales on my piano.”

One of the essay’s main areas of improvement is its overemphasis on the “story” and lack of emphasis on the reflection. The second to last paragraph about changing perspective is crucial to the essay, as it ties the anecdote to larger lessons in the writer’s life. She states that she hasn’t changed, but has only shifted perspective. Yet, we don’t get a good sense of where this realization comes from and how it impacts her life going forward.

The end of the essay offers a satisfying return to the fire imagery, and highlights the writer’s passion—the one thing that has remained constant in her life.

Essay 3: Last-Minute Switch

The morning of the Model United Nation conference, I walked into Committee feeling confident about my research. We were simulating the Nuremberg Trials – a series of post-World War II proceedings for war crimes – and my portfolio was of the Soviet Judge Major General Iona Nikitchenko. Until that day, the infamous Nazi regime had only been a chapter in my history textbook; however, the conference’s unveiling of each defendant’s crimes brought those horrors to life. The previous night, I had organized my research, proofread my position paper and gone over Judge Nikitchenko’s pertinent statements. I aimed to find the perfect balance between his stance and my own.

As I walked into committee anticipating a battle of wits, my director abruptly called out to me. “I’m afraid we’ve received a late confirmation from another delegate who will be representing Judge Nikitchenko. You, on the other hand, are now the defense attorney, Otto Stahmer.” Everyone around me buzzed around the room in excitement, coordinating with their allies and developing strategies against their enemies, oblivious to the bomb that had just dropped on me. I felt frozen in my tracks, and it seemed that only rage against the careless delegate who had confirmed her presence so late could pull me out of my trance. After having spent a month painstakingly crafting my verdicts and gathering evidence against the Nazis, I now needed to reverse my stance only three hours before the first session.

Gradually, anger gave way to utter panic. My research was fundamental to my performance, and without it, I knew I could add little to the Trials. But confident in my ability, my director optimistically recommended constructing an impromptu defense. Nervously, I began my research anew. Despite feeling hopeless, as I read through the prosecution’s arguments, I uncovered substantial loopholes. I noticed a lack of conclusive evidence against the defendants and certain inconsistencies in testimonies. My discovery energized me, inspiring me to revisit the historical overview in my conference “Background Guide” and to search the web for other relevant articles. Some Nazi prisoners had been treated as “guilty” before their court dates. While I had brushed this information under the carpet while developing my position as a judge, i t now became the focus of my defense. I began scratching out a new argument, centered on the premise that the allied countries had violated the fundamental rule that, a defendant was “not guilty” until proven otherwise.

At the end of the three hours, I felt better prepared. The first session began, and with bravado, I raised my placard to speak. Microphone in hand, I turned to face my audience. “Greetings delegates. I, Otto Stahmer would like to…….” I suddenly blanked. Utter dread permeated my body as I tried to recall my thoughts in vain. “Defence Attorney, Stahmer we’ll come back to you,” my Committee Director broke the silence as I tottered back to my seat, flushed with embarrassment. Despite my shame, I was undeterred. I needed to vindicate my director’s faith in me. I pulled out my notes, refocused, and began outlining my arguments in a more clear and direct manner. Thereafter, I spoke articulately, confidently putting forth my points. I was overjoyed when Secretariat members congratulated me on my fine performance.

Going into the conference, I believed that preparation was the key to success. I wouldn’t say I disagree with that statement now, but I believe adaptability is equally important. My ability to problem-solve in the face of an unforeseen challenge proved advantageous in the art of diplomacy. Not only did this experience transform me into a confident and eloquent delegate at that conference, but it also helped me become a more flexible and creative thinker in a variety of other capacities. Now that I know I can adapt under pressure, I look forward to engaging in activities that will push me to be even quicker on my feet.

This essay is an excellent example because it focuses on a unique challenge and is highly engaging. The writer details their experience reversing their stance in a Model UN trial with only a few hours notice, after having researched and prepared to argue the opposite perspective for a month.

Their essay is written in media res , or in the middle of the action, allowing readers to feel as if we’re there with the writer. The student openly shares their internal thoughts with us — we feel their anger and panic upon the reversal of roles. We empathize with their emotions of “utter dread” and embarrassment when they’re unable to speak.

From the essay, we learn that the student believes in thorough preparation, but can also adapt to unforeseen obstacles. They’re able to rise to the challenge and put together an impromptu argument, think critically under pressure, and recover after their initial inability to speak.

Essay 4: Music as a Coping Mechanism

CW: This essay mentions self-harm.

Sobbing uncontrollably, I parked around the corner from my best friend’s house. As I sat in the driver’s seat, I whispered the most earnest prayer I had ever offered.

Minutes before, I had driven to Colin’s house to pick up a prop for our upcoming spring musical. When I got there, his older brother, Tom, came to the door and informed me that no one else was home. “No,” I corrected, “Colin is here. He’s got a migraine.” Tom shook his head and gently told me where Colin actually was: the psychiatric unit of the local hospital. I felt a weight on my chest as I connected the dots; the terrifying picture rocked my safe little world. Tom’s words blurred as he explained Colin’s self-harm, but all I could think of was whether I could have stopped him. Those cuts on his arms had never been accidents. Colin had lied, very convincingly, many times. How could I have ignored the signs in front of me? Somehow, I managed to ask Tom whether I could see him, but he told me that visiting hours for non-family members were over for the day. I would have to move on with my afternoon.

Once my tears had subsided a little, I drove to the theater, trying to pull myself together and warm up to sing. How would I rehearse? I couldn’t sing three notes without bursting into tears. “I can’t do this,” I thought. But then I realized that the question wasn’t whether I could do it. I knew Colin would want me to push through, and something deep inside told me that music was the best way for me to process my grief. I needed to sing.

I practiced the lyrics throughout my whole drive. The first few times, I broke down in sobs. By the time I reached the theater, however, the music had calmed me. While Colin would never be far from my mind, I had to focus on the task ahead: recording vocals and then producing the video trailer that would be shown to my high school classmates. I fought to channel my worry into my recording. If my voice shook during the particularly heartfelt moments, it only added emotion and depth to my performance. I felt Colin’s absence next to me, but even before I listened to that first take, I knew it was a keeper.

With one of my hurdles behind me, I steeled myself again and prepared for the musical’s trailer. In a floor-length black cape and purple dress, I swept regally down the steps to my director, who waited outside. Under a gloomy sky that threatened to turn stormy, I boldly strode across the street, tossed a dainty yellow bouquet, and flashed confident grins at all those staring. My grief lurched inside, but I felt powerful. Despite my sadness, I could still make art.

To my own surprise, I successfully took back the day. I had felt pain, but I had not let it drown me – making music was a productive way to express my feelings than worrying. Since then, I have been learning to take better care of myself in difficult situations. That day before rehearsal, I found myself in the most troubling circumstances of my life thus far, but they did not sink me because I refused to sink. When my aunt developed cancer several months later, I knew that resolution would not come quickly, but that I could rely on music to cope with the agony, even when it would be easier to fall apart. Thankfully, Colin recovered from his injuries and was home within days. The next week, we stood together on stage at our show’s opening night. As our eyes met and our voices joined in song, I knew that music would always be our greatest mechanism for transforming pain into strength.

This essay is well-written, as we can feel the writer’s emotions through the thoughts they share, and visualize the night of the performance through their rich descriptions. Their varied sentence length also makes the essay more engaging.

That said, this essay is not a great example because of the framing of the topic. The writer can come off as insensitive since they make their friend’s struggle about themself and their emotions (and this is only worsened by the mention of their aunt’s cancer and how it was tough on them ). The essay would’ve been stronger if it focused on their guilt of not recognizing their friend’s struggles and spanned a longer period of time to demonstrate gradual relationship building and reflection. Still, this would’ve been difficult to do well.

In general, you should try to choose a challenge that is undeniably your own, and you should get at least one or two people to read your essay to give you candid feedback.

Essay 5: Dedicating a Track

“Getting beat is one thing – it’s part of competing – but I want no part in losing.” Coach Rob Stark’s motto never fails to remind me of his encouragement on early-morning bus rides to track meets around the state. I’ve always appreciated the phrase, but an experience last June helped me understand its more profound, universal meaning.

Stark, as we affectionately call him, has coached track at my high school for 25 years. His care, dedication, and emphasis on developing good character has left an enduring impact on me and hundreds of other students. Not only did he help me discover my talent and love for running, but he also taught me the importance of commitment and discipline and to approach every endeavor with the passion and intensity that I bring to running. When I learned a neighboring high school had dedicated their track to a longtime coach, I felt that Stark deserved similar honors.

Our school district’s board of education indicated they would only dedicate our track to Stark if I could demonstrate that he was extraordinary. I took charge and mobilized my teammates to distribute petitions, reach out to alumni, and compile statistics on the many team and individual champions Stark had coached over the years. We received astounding support, collecting almost 3,000 signatures and pages of endorsements from across the community. With help from my teammates, I presented this evidence to the board.

They didn’t bite.

Most members argued that dedicating the track was a low priority. Knowing that we had to act quickly to convince them of its importance, I called a team meeting where we drafted a rebuttal for the next board meeting. To my surprise, they chose me to deliver it. I was far from the best public speaker in the group, and I felt nervous about going before the unsympathetic board again. However, at that second meeting, I discovered that I enjoy articulating and arguing for something that I’m passionate about.

Public speaking resembles a cross country race. Walking to the starting line, you have to trust your training and quell your last minute doubts. When the gun fires, you can’t think too hard about anything; your performance has to be instinctual, natural, even relaxed. At the next board meeting, the podium was my starting line. As I walked up to it, familiar butterflies fluttered in my stomach. Instead of the track stretching out in front of me, I faced the vast audience of teachers, board members, and my teammates. I felt my adrenaline build, and reassured myself: I’ve put in the work, my argument is powerful and sound. As the board president told me to introduce myself, I heard, “runners set” in the back of my mind. She finished speaking, and Bang! The brief silence was the gunshot for me to begin.

The next few minutes blurred together, but when the dust settled, I knew from the board members’ expressions and the audience’s thunderous approval that I had run quite a race. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough; the board voted down our proposal. I was disappointed, but proud of myself, my team, and our collaboration off the track. We stood up for a cause we believed in, and I overcame my worries about being a leader. Although I discovered that changing the status quo through an elected body can be a painstakingly difficult process and requires perseverance, I learned that I enjoy the challenges this effort offers. Last month, one of the school board members joked that I had become a “regular” – I now often show up to meetings to advocate for a variety of causes, including better environmental practices in cafeterias and safer equipment for athletes.

Just as Stark taught me, I worked passionately to achieve my goal. I may have been beaten when I appealed to the board, but I certainly didn’t lose, and that would have made Stark proud.

While the writer didn’t succeed in getting the track dedicated to Coach Stark, their essay is certainly successful in showing their willingness to push themselves and take initiative.

The essay opens with a quote from Coach Stark that later comes full circle at the end of the essay. We learn about Stark’s impact and the motivation for trying to get the track dedicated to him.

One of the biggest areas of improvement in the intro, however, is how the essay tells us Stark’s impact rather than showing us: His care, dedication, and emphasis on developing good character has left an enduring impact on me and hundreds of other students. Not only did he help me discover my talent and love for running, but he also taught me the importance of commitment and discipline and to approach every endeavor with the passion and intensity that I bring to running.

The writer could’ve helped us feel a stronger emotional connection to Stark if they had included examples of Stark’s qualities, rather than explicitly stating them. For example, they could’ve written something like: Stark was the kind of person who would give you gas money if you told him your parents couldn’t afford to pick you up from practice. And he actually did that—several times. At track meets, alumni regularly would come talk to him and tell him how he’d changed their lives. Before Stark, I was ambivalent about running and was on the JV team, but his encouragement motivated me to run longer and harder and eventually make varsity. Because of him, I approach every endeavor with the passion and intensity that I bring to running.

The essay goes on to explain how the writer overcame their apprehension of public speaking, and likens the process of submitting an appeal to the school board to running a race. This metaphor makes the writing more engaging and allows us to feel the student’s emotions.

While the student didn’t ultimately succeed in getting the track dedicated, we learn about their resilience and initiative: I now often show up to meetings to advocate for a variety of causes, including better environmental practices in cafeterias and safer equipment for athletes.

Overall, this essay is well-done. It demonstrates growth despite failing to meet a goal, which is a unique essay structure. The running metaphor and full-circle intro/ending also elevate the writing in this essay.

Essay 6: Body Image

CW: This essay mentions eating disorders.

I press the “discover” button on my Instagram app, hoping to find enticing pictures to satisfy my boredom. Scrolling through, I see funny videos and mouth-watering pictures of food. However, one image stops me immediately. A fit teenage girl with a “perfect body” relaxes in a bikini on a beach. Beneath it, I see a slew of flattering comments. I shake with disapproval over the image’s unrealistic quality. However, part of me still wants to have a body like hers so that others will make similar comments to me.

I would like to resolve a silent issue that harms many teenagers and adults: negative self image and low self-esteem in a world where social media shapes how people view each other. When people see the façades others wear to create an “ideal” image, they can develop poor thought patterns rooted in negative self-talk. The constant comparisons to “perfect” others make people feel small. In this new digital age, it is hard to distinguish authentic from artificial representations.

When I was 11, I developed anorexia nervosa. Though I was already thin, I wanted to be skinny like the models that I saw on the magazine covers on the grocery store stands. Little did I know that those models probably also suffered from disorders, and that photoshop erased their flaws. I preferred being underweight to being healthy. No matter how little I ate or how thin I was, I always thought that I was too fat. I became obsessed with the number on the scale and would try to eat the least that I could without my parents urging me to take more. Fortunately, I stopped engaging in anorexic behaviors before middle school. However, my underlying mental habits did not change. The images that had provoked my disorder in the first place were still a constant presence in my life.

By age 15, I was in recovery from anorexia, but suffered from depression. While I used to only compare myself to models, the growth of social media meant I also compared myself to my friends and acquaintances. I felt left out when I saw my friends’ excitement about lake trips they had taken without me. As I scrolled past endless photos of my flawless, thin classmates with hundreds of likes and affirming comments, I felt my jealousy spiral. I wanted to be admired and loved by other people too. However, I felt that I could never be enough. I began to hate the way that I looked, and felt nothing in my life was good enough. I wanted to be called “perfect” and “body goals,” so I tried to only post at certain times of day to maximize my “likes.” When that didn’t work, I started to feel too anxious to post anything at all.

Body image insecurities and social media comparisons affect thousands of people – men, women, children, and adults – every day. I am lucky – after a few months of my destructive social media habits, I came across a video that pointed out the illusory nature of social media; many Instagram posts only show off good things while people hide their flaws. I began going to therapy, and recovered from my depression. To address the problem of self-image and social media, we can all focus on what matters on the inside and not what is on the surface. As an effort to become healthy internally, I started a club at my school to promote clean eating and radiating beauty from within. It has helped me grow in my confidence, and today I’m not afraid to show others my struggles by sharing my experience with eating disorders. Someday, I hope to make this club a national organization to help teenagers and adults across the country. I support the idea of body positivity and embracing difference, not “perfection.” After all, how can we be ourselves if we all look the same?

This essay covers the difficult topics of eating disorders and mental health. If you’re thinking about covering similar topics in your essay, we recommend reading our post Should You Talk About Mental Health in College Essays?

The short answer is that, yes, you can talk about mental health, but it can be risky. If you do go that route, it’s important to focus on what you learned from the experience.

We can see that the writer of this essay has been through a lot, and a strength of their essay is their vulnerability, in excerpts such as this: I wanted to be admired and loved by other people too. However, I felt that I could never be enough. I began to hate the way that I looked, and felt nothing in my life was good enough. I wanted to be called “perfect” and “body goals,” so I tried to only post at certain times of day to maximize my “likes.”

The student goes on to share how they recovered from their depression through an eye-opening video and therapy sessions, and they’re now helping others find their self-worth as well. It’s great that this essay looks towards the future and shares the writer’s goals of making their club a national organization; we can see their ambition and compassion.

The main weakness of this essay is that it doesn’t focus enough on their recovery process, which is arguably the most important part. They could’ve told us more about the video they watched or the process of starting their club and the interactions they’ve had with other members.

Still, this essay shows us that this student is honest, self-aware, and caring, which are all qualities admissions officer are looking for.

Essay 7: Health Crisis

Tears streamed down my face and my mind was paralyzed with fear. Sirens blared, but the silent panic in my own head was deafening. I was muted by shock. A few hours earlier, I had anticipated a vacation in Washington, D.C., but unexpectedly, I was rushing to the hospital behind an ambulance carrying my mother. As a fourteen-year-old from a single mother household, without a driver’s license, and seven hours from home, I was distraught over the prospect of losing the only parent I had. My fear turned into action as I made some of the bravest decisions of my life.

Three blood transfusions later, my mother’s condition was stable, but we were still states away from home, so I coordinated with my mother’s doctors in North Carolina to schedule the emergency operation that would save her life. Throughout her surgery, I anxiously awaited any word from her surgeon, but each time I asked, I was told that there had been another complication or delay. Relying on my faith and positive attitude, I remained optimistic that my mother would survive and that I could embrace new responsibilities.