- Utility Menu

- Get Involved

- News & Events

qualtrics survey

National center for teacher effectiveness.

Project Status: Past Focus Area: Teacher Effectiveness Location: Massachusetts, Georgia & Washington, D.C.

How are multiple measures used in teacher evaluation related to one another and student learning?

In July 2009, NCTE commenced a six-year effort to join disparate strands of education research, and develop a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of how to measure teacher and teaching effectiveness. NCTE is developing valid measures of effective mathematics teaching to be shared with practitioners, policymakers, and researchers. The measures may help target and plan teacher training, and improve teacher observation and feedback processes.

There are three key strands of the work:

- The core study Developing Measures of Effective Mathematics Teaching , which included a extensive data collection effort, and the development of valid and reliable tools to the field of education. Read the research overview .

- Supplementary studies that aim to be responsive to the needs of education practitioners and policymakers. These studies investigate professional environments , teacher effects , teacher evaluation systems , and item response theory .

- National leadership activities such as conferences and webinars. You can learn more about these topics by accessing our resources below.

The project is led by Harvard Graduate School of Education Professors Thomas J. Kane and Heather Hill, Dartmouth College Professor Douglas O. Staiger, and Project Director Corinne Herlihy.

Johanna Barmore

... Read more about Johanna Barmore

David Blazar

... Read more about David Blazar

Elizabeth Cascio

Job Market Paper: Breaking rank? An investigation of families’ preferences for schools and their causal moderators Dissertation Committee: Martin West, David Deming, Desmond Ang Research Interests: School Integration, School Choice, Racial Attitudes/Bias, Prosocial Behavior, Sociopolitical Preferences, Applied Quantitative Methods in Education Research PIER Summer Residency Placement: Wake County Public Schools

Email Website Twitter

Claire Gogolen

- Mathematical Quality of Instruction (MQI)

- Exploring Explanations for the "Weak" Relationship Between Value Added and Observation-Based Measures of Teacher Performance

- Effective teaching in elementary mathematics: Identifying classroom practices that support student achievement

- NCTE Student Assessments

- Technical Report: Creation and Dissemination of Upper-Elementary Mathematics Assessment Modules

- Approximate measurement invariance in cross-classified rater-mediated assessments

- Year-to-Year Stability in Measures of Teachers and Teaching

- Teachers' Knowledge of Students: Defining a Domain

- Teacher Characteristics and Student Learning: Toward a More Comprehensive Examination of the Association

- Attending to General and Content-Specific Dimensions of Teaching: Exploring Factors Across Two Observation Instruments

Do Value-Added Estimates Identify Causal Effects of Teachers and Schools?

CEPR Faculty Director Thomas Kane discusses value-added estimates in the following Brookings Institution paper.... Read more about Do Value-Added Estimates Identify Causal Effects of Teachers and Schools?

Who is an Effective Teacher?

CEPR Faculty Director Thomas Kane discusses the minimum standard of effectiveness for teachers in the following Brookings Institution paper.... Read more about Who is an Effective Teacher?

Prioritizing Teaching Quality in a New System of Teacher Evalaution

National Center for Teacher Effectiveness (NCTE) leaders Heather Hill and Corinne Herlihy emphasize the importance of focusing on the quality of teaching, and not "teacher quality," in the following article published in the Education Outlook Series by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

Teachers are the most important school-level factor in student success—but as any parent knows, all teachers are not created equal. Reforms to the current quite cursory teacher evaluation system, if done well, have the potential to remove the...

Education Agencies

With the goal of positioning ourselves as a national resource on teacher effectiveness research, we have partnered with four school districts on the east coast to conduct rigorous research, develop tools, and share best practices and lessons learned in teacher evaluation and professional development.

The National Center for Teacher Effectiveness is supported by the Institute of Education Sciences , U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305C090023 to the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University.

- Focus Areas

Featured Resource

Explaining teacher effects on achievement using measures from multiple research traditions, conference resources.

Beyond the Numbers Convening (2014)

Putting the Pieces Together: Taking Improved Teacher Evaluation to Scale (2011)

Access the NCTE instruments, data archive, and video library

You may also like

- Middle School Mathematics Teachers and Teaching Survey

- Developing Common Core Classrooms Through Rubric-Based Coaching

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, rediscovering teaching in university: a scoping review of teacher effectiveness in higher education.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

- 2 Department of Psychology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 3 Department of Training and Education Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

- 4 Department of Psychology, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece

- 5 Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, University Research Center of Loannina (U.R.C.I.), Ioannina, Greece

Although teacher effectiveness plays a critical role in the learning process, little is known about its conceptualization and assessment, particularly in higher education (HE). This review aims to fill this gap by (a) listing the literature on teacher effectiveness, (b) identifying the instruments that have been used to assess teacher effectiveness (HE), and (c) highlighting the most effective teaching approaches based on the relevant literature. The selection process considered studies published since 1990 and conducted in higher education contexts with students. The research articles measured instructional processes and faculty effectiveness in terms of student outcomes, focusing on student achievement and student satisfaction. In reviewing the international research, special attention was paid to Southeastern Europe and Greece in particular. After a thorough review, the analysis revealed 26 studies. The results show that there is no universal definition of effective higher education teaching. Effective teaching may manifest itself in high scores on student performance assessments or in rewarding classroom interactions. Based on this principle, the way teacher effectiveness is defined is closely linked to proposed solutions in educational policy. Furthermore, research has shown that student-centered teaching styles are perceived by students as more effective, engaging, and performance-enhancing. However, several studies have not clarified why different teachers use different teaching styles in similar contexts. This review represents a step forward in our understanding of teacher effectiveness in HE. Nonetheless, effective teaching strategies could be better conceptualized through future research aimed at assessing the contextual nature of teaching along with student perceptions of effectiveness and expectations for an effective classroom climate.

Introduction

The quality of teaching and learning in higher education (HE) has gained worldwide attention in the last decade ( Devlin, 2007 ; Henard and Roseveare, 2012 ; Cardoso et al., 2015 ; Milienos et al., 2021 ). The new educational vision of higher education is to ensure effective teaching in universities and to be able to determine this effectiveness. University teaching can be defined as an academic activity that requires extensive professional skills and practices, as well as a high level of disciplinary and other contextual expertise. Attempting to apply effective teaching approaches as a university teacher ensures the foundation for a quality learning and teaching context ( Tadesse and Khalid, 2022 ). Such an attempt is critical for all teaching staff, academic researchers, higher education institutions, and indeed for the entire higher education sector, both nationally and internationally.

Altbach et al. (2009) argue that there has been an unprecedented shift in the goals of higher education over the past 50 years. Society should be well prepared to respond effectively to the challenges of the global marketplace and high competitiveness by proactively engaging in the development, adaptability, and utilization of knowledge. All this could serve as a foundation for national growth in the service and manufacturing sectors ( Zuñiga et al., 2010 ). In this context, higher education plays an important and crucial role in the development of human capital, entrepreneurial perspectives, and innovative practices related to a sustainable knowledge economy within the new teaching and learning paradigm ( Dill and Van Vught, 2010 ).

The process of evaluating teacher effectiveness has changed over time, as has the definition of what constitutes effective teaching. Effective teaching has been defined in many ways over the years ( Cruickshank and Haefele, 1990 ; Cheng and Tsui, 1999 ; Campbell et al., 2004 ; Muijs, 2006 ; Zuñiga et al., 2010 ; Hoidn et al., 2021 ), and approaches to assessing teacher effectiveness have changed with the development of different definitions and beliefs about what to measure. There is consensus that high-quality teaching is important and that it may be the most important education-related factor in improving student achievement ( Ding and Sherman, 2006 ; Devlin and Samarawickrema, 2010 ). However, the measurement of teacher effectiveness has remained vague, in part because there has been no consensus on what an effective teacher is and does. In a discussion of research-based indicators of effective teaching, Cruickshank and Haefele (1990) pointed out that “a tremendous underlying problem in evaluating teachers is that there is no agreement on what constitutes good or effective teaching” (p. 34).

Faculty members are evaluated in a variety of ways to determine whether they should be promoted or rewarded and to potentially improve their performance. An appropriate measure of faculty members' research productivity that is often used is the number and quality of published scholarly papers and reports. A similar measure of teaching effectiveness is not as readily available ( McBean and Al-Nassri, 1982 ; Khandan and Shannon, 2021 ). Aside from the fact that there is no clear agreement on what an effective teacher is and does-or perhaps because of it-there is no universally accepted method for evaluating teacher effectiveness. Some of the common evaluation methods refer to classroom observations, which aim to measure teachers' approaches to a standard of effective teaching, and value-added models, which aim to measure the extent to which teachers can contribute to their students' achievement growth.

The purpose of this review paper is to improve understanding of and further conceptualize teacher effectiveness in higher education from both a practical and research-oriented perspective. The processes that occur in the classroom and student outcomes that relate to performance improvement are the focus of this review, as these issues are prevalent in the current educational policy landscape. Thus, the rationale for this review lies primarily in the complexity of teaching and learning and the relative novelty of the widespread inclusion of co-teaching in teacher education. More specifically, through a rigorous and systematic process, we aim to provide a comprehensive descriptive overview of the scope, range, and nature of research on teacher effectiveness in higher education. In addition, we provide a foundation for future research and practice in this area by presenting in three distinct ways (a) the range of findings, (b) clarifying conceptual boundaries, and (c) suggesting refinements to operational definitions of teacher effectiveness in higher education.

A Complicating Concept

Teaching and learning are two sides of the same coin. The most recognized criterion for measuring teaching effectiveness is the amount of student learning ( Marsh, 1984 ; Devlin and Samarawickrema, 2010 ; Richardson, 2017 ; Vermunt and Donche, 2017 ). There are consistently high positive correlations between students' ratings of the amount learned in the course and their overall ratings of the instructor and the course: those who learn more give higher ratings to their instructors ( Cohen, 1981 ; Theall and Franklin, 2001 ). In addition, students' perceptions of the learning context are known to influence the methods and tactics of learning ( Karagiannopoulou and Milienos, 2015 ). Although this relationship between learning and teaching is discussed as reciprocal ( Richardson and Watt, 2006 ), studies have clearly shown that students' perceptions of the learning environment have an impact on learning methods, which in turn influences academic performance ( Karagiannopoulou and Christodoulides, 2005 ). The literature on instruction is replete with well-researched ways in which teachers can, first, teach content and skills that enhance students' learning opportunities, and second, assess learning through various types of assessments ( Karagiannopoulou and Milienos, 2013 ; Entwistle and Karagiannopoulou, 2014 ). Moreover, the literature is equally focused on formulating suggestions about what not to do in the classroom. Yet, there is no rulebook on what teaching methods are most appropriate and effective for the skills and/or content being taught. Students often do not know whether the method chosen by an individual instructor was the best teaching method or simply the method with which the instructor felt most comfortable ( Ramsden, 1991 ; Pratt, 1998 ; Bates and Poole, 2003 ).

More specifically, although research shows that college teachers have the greatest impact on student achievement ( Gibbs and Jenkins, 2014 ), defining the characteristics that describe quality teachers and measuring the evidence that would capture effectiveness remains quite problematic in education ( Partee, 2012 ). Nonetheless, there have been few attempts to define those particular qualities-tolerating ambiguity, demonstrating authenticity and empathy-that characterize “outstanding teachers” and that are associated with better personal understanding of students ( Fraser et al., 2010 ; Karagiannopoulou and Entwistle, 2019 ). Researchers contend that while there are many notable theories and ideas about assessment, there is no single tool that can be used to quickly and accurately determine and evaluate teacher effectiveness. There is talk of the need for teachers and stakeholders to cultivate a shared understanding of good practice ( Yorke, 2003 ; Leiber, 2018 ).

There is a need to better understand the notion of teacher effectiveness in higher education, specifically what it is and whether and how it can be achieved. Therefore, the focus of this review was to examine the nature and scope of the empirical literature in this area, particularly studies that use observational data, as observational instruments and frameworks are an important method for understanding teacher effectiveness in practice. For the purposes of this study, the term “instrument” refers to any structured observational scale or organizational framework used to measure (or organize data) aspects of teacher effectiveness in higher education. Our scoping review served two purposeful research questions as follows:

(1) How has teacher effectiveness been conceptualized in empirical research to date?

(2) What dimensions can be distinguished?

The study also aims to provide further insights for pedagogical practice as to whether important lessons for quality teaching can be drawn from this literature.

Given the exploratory nature of the research questions, a scoping review method was used. Scoping reviews are a relatively new approach for which there is not yet a universal study definition or definitive approach ( Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ; Anderson et al., 2008 ; Davis et al., 2009 ; Levac et al., 2010 ; Daudt et al., 2013 ), particularly in the field of education ( Egan et al., 2017 ; Hariharasudan and Kot, 2018 ).

Scoping studies represent an approach to reviewing research findings to contextualize knowledge in terms of:

- Examining the scope, diversity, and nature of research activities.

- Determining the appropriateness of a full systematic review—Abridging and disseminating research findings.

- Identifying research gaps in the existing literature ( Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ).

A scoping review is not a linear process (as typically prescribed in the protocol for systematic review), but a back and forth between early results and new findings, with changes in search terms and even questions ( Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ).

Thus, in accordance with Arksey and O'Malley's framework for scoping reviews, an “iterative” process was undertaken ( Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 , p. 8): the search terms defined below were not fixed from the outset, but were distinguished as the process progressed so that all relevant literature could be captured.

More specifically, the scoping review method used in this study was initially guided by Arksey and O'Malley's (2005 ) five-stage framework, but then our research team, which consisted of four researchers, decided to add an additional stage after considering Daudt et al. (2013) , who suggested additional recommendations.

Originally, the sixth stage was intended to be a voluntary stage where experts in areas related to the research question would be asked to review and comment on the stages of the study to ensure that it was conducted efficiently and proceeded without bias. Both Levac et al. (2010) and Daudt et al. (2013) emphasized that this phase is part of the process, and it is retained for this review.

Thus, we went through each stage of the review process independently. Conflicts were collaboratively resolved after each step.

Search Strategy and Source Selection

In this systematic scoping review ( Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ; Daudt et al., 2013 ; Andersen et al., 2021 ), a comprehensive search strategy was developed. After an initial search of the topic area in collaboration with an information search expert.

Definitions and understandings of teacher effectiveness vary in many ways. In general, the term seems to be associated with the “how” of teaching (i.e., teaching style and/or learning environment, student engagement) rather than the “what” of teaching (i.e., curriculum content). However, Gill and Singh (2020) note that the above term is sometimes used to refer to both. Based on this distinction, we focused on the “how” of teaching (i.e., teaching style and/or learning environment, course difficulty, student engagement).

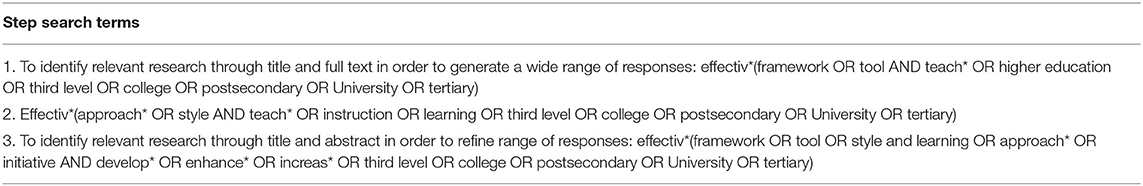

Parameters were set for the study that influenced the scope of the search. Specifically, only studies published since 1990 and related to the relationship between teacher effectiveness and teaching evaluation were considered. In addition, only studies that were available in English and only studies in peer-reviewed journals were considered. A systematic search was conducted in the following electronic collections and databases: EBSCOhost Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, ScienceDirect, Education Research Complete, and Web of Science (Science and Social Science Index). Searches for titles, abstracts, and keywords were also conducted using the search terms listed in Table 1 . To be more specific, we matched terms from higher education (“higher education,” “universit * ,” “University * ,” “postsecondary”) with search terms from “effectiveness” (“teaching effectively * ,” “effective teaching,” “effective learning,” “effective instruction”) in this review page.

Table 1 . Sample of search terms for the ERIC database.

The literature on teacher effectiveness is extensive and fragmented. Researchers working in various fields theorized, conduct studies, and publish articles in various journals. Often, researchers do not attempt to identify connections among these disparate findings, or they do not build on findings from other fields. This could mean that the knowledge acquired is less cumulative than might be optimal. This means that views of research in such areas depend on the conceptual frameworks adopted by individual research papers ( Okoli, 2019 ). The categories selected for our review were deemed useful; however, scholars in other disciplines may have used different categories.

Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The identification and selection of articles for this review began with broad categories and many search terms ( Sibgatullin et al., 2022 ). The authors gradually narrowed the group of studies to those that met specific criteria. More stringent standards and criteria could have been applied. Dynarski (2008 , p. 27) stated in this regard that: “Selective exclusion of research requires great caution, as selectivity can be interpreted as compromising scientific objectivity for purposes that educators cannot discern and may misinterpret.” Consistent with Dynarski's (2008) statement, this review refrained from using narrow criteria so that studies that might be informative for specific purposes or audiences were included. Dynarski also stated:

“Of course, it is possible that the results of some studies are due to publication bias or that they result from local conditions that are unusual or difficult to replicate. But if syntheses review all the evidence and apply sound standards, educators can make up their own minds about whether the results are credible or whether the implementation conditions are unrealistic and not useful to them.” (p. 28).

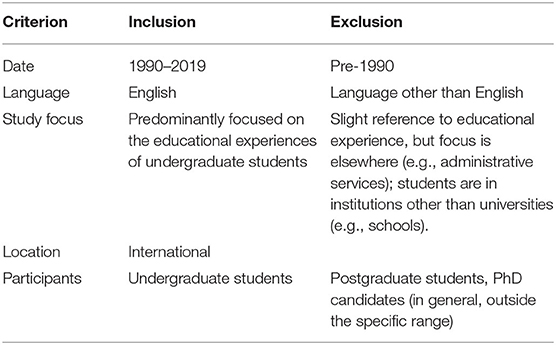

The breadth of the above search terms resulted in a wide range of items. After removing duplicates, this initial search yielded more than 1,080 studies. To narrow the results, abstracts were reviewed to determine if studies met the following criteria (see Table 2 ):

Table 2 . Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Research Methodology . Since the main objective of this review is to identify frameworks for teaching effectiveness and related characteristics, both qualitative and quantitative research were considered.

Participants . The research must have been conducted in a higher education context with undergraduate students, either as part of a module or as a stand-alone module. We did not exclude studies based on a specific discipline.

Location . The research was conducted internationally, with a particular focus on Southern European countries and Greece in particular.

Relevance . Finally, the work under review must state in its own words that the goal of the research was to improve teacher effectiveness in order to be considered appropriate.

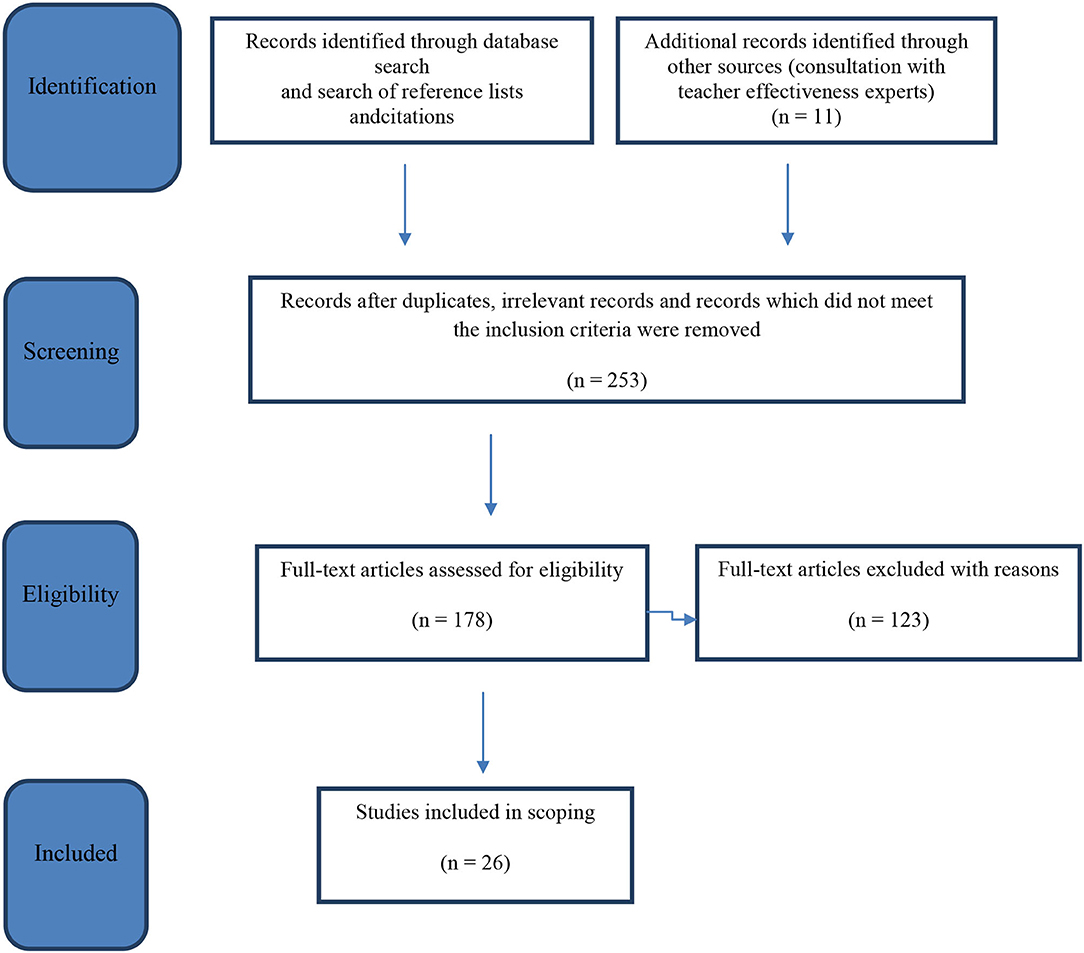

Approximately 250 articles met the above criteria and were therefore included in the next phase. Subsequently, this pool of the initially selected 250 articles was reviewed for relevance and methodological rigor. Articles were selected according to the Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement ( Moher et al., 2009 ).

For studies to be included in this review, they should also meet a number of additional criteria:

- Use an instrument to measure teacher effectiveness or instructional practice.

- Include a measure of student outcomes or impact on teacher effectiveness.

- They should report methods that meet high research quality standards, such as reliable and validated instruments, appropriate study design, and necessary controls.

In the next phase, the resulting collection of studies was evaluated. Additional exclusions were made if a closer reading revealed that they were of a different scope or did not meet the quality standards of this synthesis. Specifically, research was excluded if it was of poor quality, did not fit the topic, was beyond the scope, focused on schooling, or even lacked descriptions of data and methods. The overall analysis yielded 26 studies ( Figure 1 ) that were thoroughly reviewed. Full-text versions of the articles were obtained, and each article was reviewed and deemed appropriate by members of the research team. A review of the reference lists for each article also helped to identify additional relevant literature that could be considered for the study.

Figure 1 . PRISMA flow diagram (adapted from Moher et al., 2009 ).

As mentioned earlier, the search was narrowed by focusing on studies that measured instructional processes and outcomes that impacted student outcomes. Particular attention was paid to studies that measured teacher effectiveness in terms of adding value to student achievement and satisfaction.

This narrowing of scope was important to ensure that the amount of literature to be reviewed and summarized was sufficient to turn it into a practical and informative paper.

Quality Appraisal

All 29 identified studies were assessed for methodological quality using the Crombie model for critical appraisal of qualitative or quantitative research ( Glasper and Carpenter, 2021 ). Although not strictly required in a scoping study ( Engel-Yeger et al., 2018 ), critical appraisal involved the use of a series of questions that serve as a process or framework for assessing studies for their trustworthiness, value, and relevance in a particular context, culminating in a critique of each research article's objective(s), method(s), findings, and conclusions ( Glasper and Carpenter, 2021 ). Three studies were excluded due to lack of trustworthiness, leaving 26 studies (five descriptive papers: 2, 6, 8, 16, 17; twelve qualitative studies: 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 11, 13, 14, 19, 20, 23, 26; eight quantitative studies: 4, 9, 15, 21, 22, 24, 25; and one that used mixed methods: 12) to review and summarize. The selected studies are marked with an * in the References section.

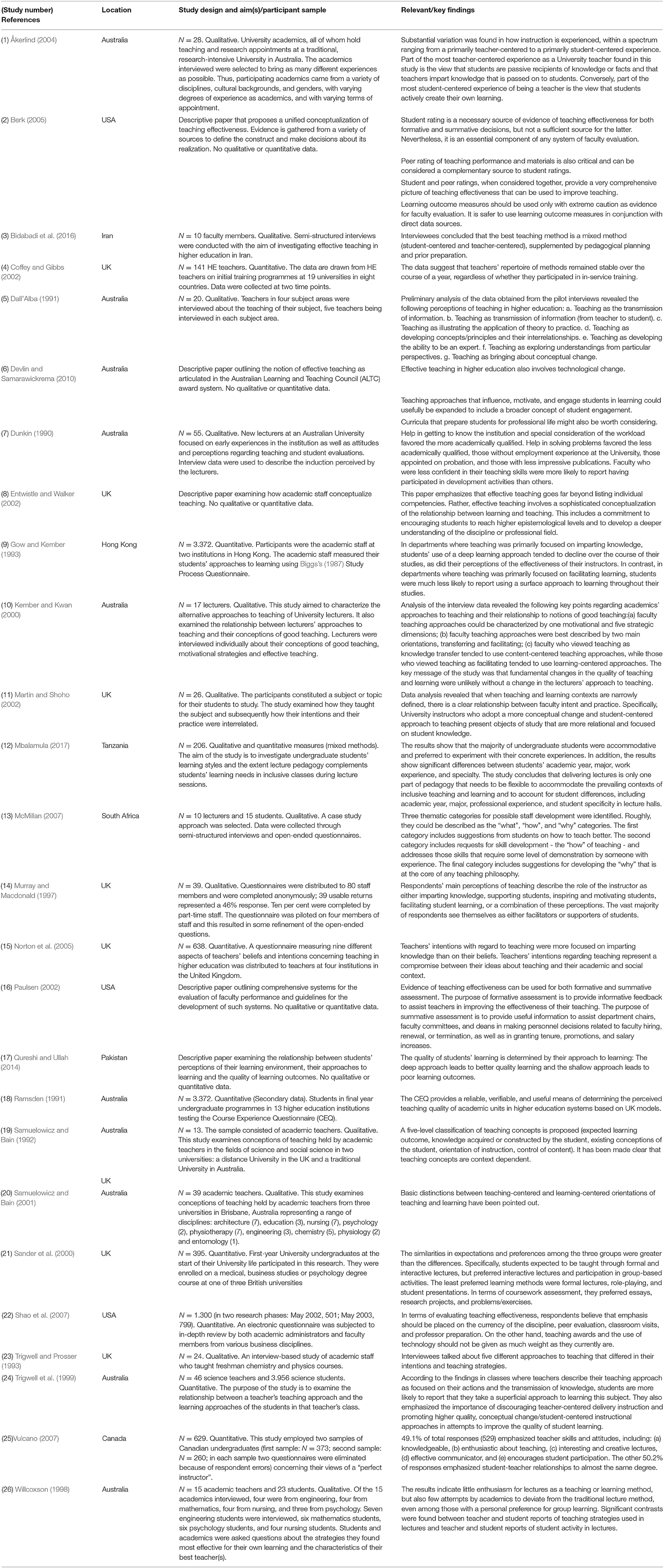

This scoping review resulted in 26 articles from five countries. Of these, 9 studies were conducted in Australia, seven in the United Kingdom, three in the United States, one in Canada, one in Hong Kong, one in Iran, one in South Africa, one in Pakistan, one in Tanzania, and one in both Australia and the United Kingdom. Conspicuous by its absence was literature from Europe. In this section, we present articles that were the focus of our original research questions.

To improve conceptual clarity and determine the nature and scope of research on effectiveness in higher education, we first present the methodological characteristics of the studies descriptively (in alphabetical order of the last names of the first authors of each article). Second, our analysis focuses on how teacher effectiveness is conceptualized and implemented in higher education. We also provide a nuanced discussion of the findings and phenomena within these studies. In addition, noteworthy trends and implications for teacher efficacy and for future theoretical and empirical studies are discussed. Rather than providing the results of statistical analyses or summarizing the overall findings, we have chosen to describe the characteristics of typical manifestations of teacher effectiveness in higher education and how it has been researched to guide academic staff and researchers (see Table 3 ).

Table 3 . Included studies from 1990 (in alphabetical order).

How Has Teacher Effectiveness Been Conceptualized in Empirical Research to Date?

Teacher effectiveness in higher education can be viewed from three different but interrelated perspectives: Measuring inputs, processes, and outputs ( Devlin and Samarawickrema, 2010 ). Input refers to what a faculty member brings to their position. It is generally measured and includes elements such as the teacher's background, beliefs, expectations, experience, pedagogical and content knowledge, certification and licensure, and educational background. These measures are sometimes defined in the literature with the term “teacher quality” ( Qureshi and Ullah, 2014 ). Processes, on the other hand, refer to the interaction between teachers and students. This may include a teacher's professional activities within the larger University community. Outcomes are the results of instructional processes, such as the impact on student achievement, graduation rates, student behavior, engagement, attitudes, and social-emotional wellbeing. Other outcomes may include contributions to the University or community in the form of taking on leadership roles or training other faculty.

Numerous attempts have been made to classify the characteristics of teacher effectiveness. Numerous theoretical perspectives have been used, based on qualitative or quantitative approaches, and from different disciplinary viewpoints ( McMillan, 2007 ). Student perspectives have also been used in attempts to classify ( Vulcano, 2007 ). However, there is no universally accepted definition of effective higher education teaching ( Johnson and Ryan, 2000 ; Trigwell, 2001 ; Paulsen, 2002 ).

Effective teaching is generally understood to be instruction that is focused and centered on students and their learning ( Devlin and Samarawickrema, 2010 ; Qureshi and Ullah, 2014 ).

Given the importance of these distinctions, it is suggested that the term teacher effectiveness be used, but much more broadly than is common in current policy discussions and the specific frameworks under study. In the following lines of this section, a more nuanced definition of teacher effectiveness is provided that encompasses both the broad tasks teachers perform and the various outcomes that education stakeholders value.

Gradually, policy discussions tend to define teacher effectiveness as a teacher's ability to make higher than expected progress as reflected in student standardized test scores. This emphasis on attributing success on standardized tests to teachers and measuring the outcome of teaching by averaging test scores has a number of strengths. However, the definition also has significant shortcomings and has been viewed with skepticism.

The first limitation is related to the assumptions about causality that underlie this approach. If one directly relates student achievement to teacher effectiveness, one must determine what portion of the effectiveness score is attributable solely to the teacher. This determination is difficult not only for practical reasons, but also for logical reasons: It requires assumptions that may be irrational. According to Fenstermacher and Richardson (2005 , pp. 190–191), “[...] learning requires a combination of circumstances that go far beyond the actions of a teacher.”

It is worth noting that teacher effectiveness can be measured without considering classroom climate if teacher effectiveness is narrowly defined as a teacher's apparent impact on his or her students' learning, as is the case with standardized tests. Adopting this limited aspect ignores other important teacher resources and behaviors that contribute to successful learning.

Another criticism of this definition is that too narrow a focus on standardized test scores as the most important and reliable-and in some cases only-measure of student outcomes is not always consistent with all perspectives on effective teaching and learning ( Bassey et al., 2019 ). A review of the literature on teacher evaluation revealed that researchers' definitions of teacher effectiveness are more expansive. More specifically, according to Campbell et al. (2004 , p. 3), “teacher effectiveness is the impact that classroom factors, such as instructional practices, teacher expectations, classroom organization, and use of classroom resources, have on student achievement.” This definition describes what happens in the classroom, but the measure of effectiveness is still student achievement. However, many researchers believe that there are other important outcomes that make for effective teachers besides student performance on standardized tests ( Atkins and Brown, 2002 ). A number of studies looking at factors that predict academic achievement have found that the influence of students' perceptions of the learning environment is a stronger predictor of academic achievement than prior academic ability, possibly leading to better learning outcomes ( Karagiannopoulou and Christodoulides, 2005 ; Richardson and Watt, 2006 ; Entwistle, 2009 ).

Student achievement growth should be an important element in assessing teacher effectiveness; however, criticism of the performance-based view of teacher effectiveness is warranted. A broader view of teacher effectiveness that includes other features of teaching needs to be part of the discussion.

Teaching effectiveness is a controversial, value-laden concept with varying definitions. Therefore, a meaningful definition of teaching effectiveness should be related to the specific context in which teaching is assessed ( Laurillard, 2002 ; Devlin and Samarawickrema, 2010 ). Communities should openly classify the values and assumptions that underpin their understanding of what it means to be an effective teacher and what they define as best practices ( Fry et al., 2008 ). For example, a definition might reflect a college's mission, the unique practices of an academic discipline, or the values underlying a particular teaching award.

Thus, there are three elements to consider when evaluating the effectiveness of teaching in a given context:

- Criteria: Characteristics of effective teaching.

- Evidence: Documentation of instruction.

- Standards: expectations of quality and quantity.

What Dimensions of Teacher Effectiveness Can Be Distinguished?

Even when teaching analogous courses, different teachers teach in different ways, and this can affect their students' satisfaction, motivation, and achievement ( Theall and Franklin, 2001 ).

Approaches to Teaching in Higher Education

Trigwell and Prosser (1993 ) conducted an interview-based study of 24 academic staff members who taught freshman chemistry and physics courses. They identified five different teaching approaches that differed in terms of their goals and teaching strategies. Some methods were teacher-oriented and aimed at conveying information to students, while other techniques were “student-oriented and aimed at effecting conceptual change in students” ( Prosser and Trigwell, 1999 , pp. 153–154). Trigwell and Prosser also developed a quantitative instrument, the Approaches to Teaching Inventory (ATI), to measure the teaching practices of a larger number of teachers. This questionnaire “contained 16 items that measured teachers' intentions and strategies related to two basic approaches to teaching: a conceptual change or student-centered approach and a delivery or teacher-centered approach” ( Prosser and Trigwell, 1999 , pp. 154–157).

Accordingly, using this questionnaire, Coffey and Gibbs (2002 ) found that teachers who took a student-centered approach reported using a more specific repertoire of teaching methods than teachers who took a teacher-centered approach.

In addition, Trigwell et al. (1999 ) demonstrated that students whose teachers took a student-centered approach showed a deeper approach to learning according to their scores on ATI and were rated as effective. At the same time, they show a less superficial approach to learning than students whose teachers took a teacher-centered approach. Moreover, when teaching methods involved a sense of acceptance and mutual respect for each other's thinking, a class climate emerged that fostered a “meeting of the minds” ( Karagiannopoulou and Entwistle, 2013 ).

Sander et al. (2000 ) argued that students expected to be taught primarily through frontal lectures but preferred more interactive and group-based activities, even calling them more effective.

However, these studies do not shed light on why different teachers use different teaching methods in similar contexts. Some researchers have attributed this to constitutional characteristics of the teachers themselves: different teaching styles ( Mbalamula, 2017 ), thinking styles, or personality traits ( Zhang and Sternberg, 2002 ). This is not entirely acceptable, as it remains unclear why teaching styles should evolve as a result of training ( Gibbs and Coffey, 2004 ) or experience ( Åkerlind, 2004 ). Other scholars have underscored that different approaches to teaching reflect different fundamental conceptions of teaching and that teaching approaches improve as more sophisticated and refined conceptions are acquired ( Entwistle and Walker, 2002 ; Bidabadi et al., 2016 ).

Conceptions of Teaching in Higher Education

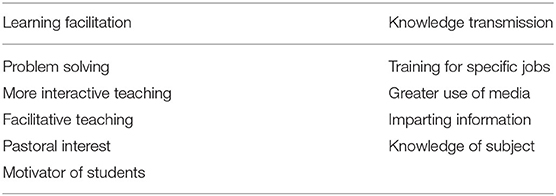

Interview-based research has confirmed a number of different teaching beliefs that also determine teaching effectiveness among University faculty ( Dunkin, 1990 ; Dall'Alba, 1991 ; Samuelowicz and Bain, 1992 , 2001 ; Pratt, 1998 ; Willcoxson, 1998 ). Gow and Kember (1993) used the analytic categories that emerged from their own interviews to create a questionnaire on teaching beliefs (see Table 4 ). The questionnaire contained 46 items measuring nine subscales subsumed under two broad orientations to teaching.

Table 4 . Gow and Kember's (1993) orientations to teaching.

Gow and Kember (1993) obtained 170 responses to this questionnaire from staff at two institutions in Hong Kong and calculated student learning approaches using Biggs's (1987) Study Process Questionnaire. In departments where teaching was primarily focused on imparting knowledge, students' use of a deep learning approach tended to decline over the course of their studies, and with it their perceptions of their teachers' effectiveness.

On the other hand, students in departments where the main idea of teaching was to facilitate learning reported less use of a surface approach to learning ( Kember and Gow, 1994 ).

Subsequently, Kember (1997) reviewed the accumulating interview-based research on this topic. While noting that there was some variation in terminology, he argued that most of the studies adhered to five conceptions of instruction that can be located on a path from a fully teacher-centered, content-oriented conception of instruction to a fully student-centered and learner-oriented conception of teaching and teacher effectiveness as follows ( Kember, 1998 ):

▪ Teaching as communicating and reporting information.

▪ Teaching as transmission of structured knowledge.

▪ Teaching as interaction between the teacher and the student.

▪ Teaching as the promotion of understanding on the part of the student.

▪ Teaching as generating conceptual change and intellectual development in the student.

The relationship between students' perceptions of the teaching and learning environment could lead to more effective teaching in terms of the quality of student learning. Recent studies take a step beyond established theories ( Kember, 1998 ; Prosser et al., 2007 ) and propose an additional sixth approach to teaching that considers the experiences of “meeting the mind” and supports perceptions related to emotional-cognitive teaching experiences ( Entwistle, 2018 ; Karagiannopoulou and Entwistle, 2019 ).

Beliefs and Contexts vs. Objectives in Teaching

There is substantial indeterminacy-even fuzziness-in the conception of approaches to teaching and teaching effectiveness in higher education. On the one hand, a teacher's approach to teaching and teaching effectiveness may reflect the teaching behavior that, other things being equal, the teacher finds most comfortable. In this case, it is likely to be closely related to the teacher's conception of teaching ( Kember and Kwan, 2000 ). On the other hand, an approach to teaching and teaching effectiveness might reflect a behavior that the teacher is compelled to engage in by the curriculum, the institution, or the students themselves. In this case, it is probably more closely related to the teacher's perception of the teaching environment than to his or her own conception of teaching: It embodies a specific response to a particular teaching situation that is directly manifested in the teacher's classroom behavior ( Martin et al., 2002 ).

According to Pratt (1998) , there is an internal balance between the activities, intentions, and principles of different teachers and the specific environments in which they operate.

Accordingly, Dunkin (1990 ) introduced the term “orientations in relation to teaching effectiveness” in a similar way. While, Gow and Kember (1993) used the term only to refer to broad categories of ideas, their questionnaire also included items that might refer to teaching purposes rather than principles of teaching.

Despite these assumptions about substantial agreement between teachers' views and purposes, Samuelowicz and Bain (1992 ) found evidence in their interviews that teachers may have adopted two different kinds of conceptions of teaching effectiveness: the “ideal” and the “working.”

From the limited data available, it appears that academic teachers' articulated instructional goals are consistent with their “ideal” conception of teaching, while their teaching practices, including assessment, reflect their “working” conception of teaching. If this is the case, research could profitably be directed toward the factors (teacher-, student-, and institution-related) that prevent academic teachers from acting in accordance with their ideal conception of teaching, thus helping to solve one of the puzzles of higher education-the discrepancy between stated goals (fostering critical thinking) and teaching practices (unimaginative delivery of content and testing of factual knowledge) so often referred to in the literature ( Samuelowicz and Bain, 1992 , p. 110).

Murray and Macdonald (1997 ) found that there are differences between teachers' beliefs and perceptions of teaching effectiveness and their actual teaching practices and actions. This discrepancy appears to be more common among teachers whose beliefs about learning are more focused on supporting students. Murray and Macdonald suggested three possible explanations for this phenomenon: teachers may be dissatisfied and discouraged in their actual goals by environmental constraints; teachers' actual beliefs about teaching may be more accurately reflected in their actual actions than in their conceptions or principles; and teachers may not have experienced adequate training or staff development to facilitate operationalizing their conceptions of teaching into applicable teaching strategies.

This paper has attempted to capture teaching effectiveness in HE (i.e., the dimensions and approaches to teaching effectiveness) to determine how scholars have conceptualized, described, and researched this phenomenon. The wide range of definitions used to describe teaching effectiveness is a testament to the continuous evolution of the teaching and learning process.

Considering that the first article cited in this review was published in 1990, there is still no consensus on how to define and identify effective teaching, despite the large amount of research that has been conducted in the area of teacher effectiveness over the years.

The data examined in this scoping study have shown a lack of evidence for a common and widely accepted definition. This is perhaps not surprising given that teacher effectiveness is a very broad concept that encompasses a wide range of variables that need to be considered (i.e., imponderable and predictable factors), beginning with the bilateral relationship and connection between teaching and learning, and thus between teachers and students. Shedding light on the ways in which teacher effectiveness is defined is important for two main reasons. First and foremost, what is measured is a consideration of what is valued, and therefore what is measured is valued ( Goe et al., 2008 ). Definitions recommend and shape what needs to be calculated. For example, if policy discussions are only about standardized tests, important outcomes can be truncated to those that can be calculated using standardized test scores. In contrast, when policy discussions focus on teacher-student interfaces, the focus shifts to classrooms and documenting effective interactions between teachers and their students.

Moreover, different definitions lead to different policy solutions. When the discussion focuses on teacher effectiveness, the conversation potentially leads to improving teachers' scores on measures of knowledge or signals of that knowledge, such as certification. When the conversation is about instructional practices or standards, specific instructional concepts, practices, or approaches come into focus.

It is also noteworthy that a high percentage of the articles came from the Anglo-American context (i.e., 7 from the United Kingdom and 3 from the United States). The remaining articles were either from more economically advanced nations (e.g., Australia, Canada, and Hong Kong) or from low-income countries (e.g., Tanzania and Pakistan). This suggests that teacher effectiveness in HE is of particular interest in certain international settings. The concept of teacher effectiveness in HE was popularized by countries in the global North in the second half of the twentieth century and has traditionally taken on less importance in less economically developed countries-probably because of financial constraints, different political situations and social contexts, and/or different educational conditions. Nevertheless, some of them-such as Pakistan and Tanzania, which are officially moving from low-income to middle-income country status in 2020 ( Diao et al., 2020 )-are trying to gain a foothold in the field of teaching innovation and provide educational opportunities worthy of those in the developed world, with the goal of reducing their out- migration rates in favor of better learning and work opportunities.

Limitations

Scoping review studies have several limitations. Scoping studies identify the amount and type of literature that currently exists in the area of interest rather than assessing the quality of that evidence. Consequently, they cannot determine whether particular studies provide robust or generalizable results ( Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ). In addition, scoping studies do not aim to summarize findings or combine results from different studies ( Arksey and O'Malley, 2005 ). This review is limited to measuring teacher effectiveness and does not address methods for measuring the impact of universities, the effectiveness of curricula or the implementation of professional development (unless they include measures that explicitly apply to teachers), or other evaluations of educational interventions or frameworks. Although these are important and related topics, they are beyond the scope of this review.

In addition, for feasibility reasons, this study only considered articles written in English, which may have resulted in applicable articles not being included in the review. Another limitation of this study is that proxies for the term “teacher effectiveness”, such as “teacher mastery”, were not included in the key search terms. In addition, searches of electronic databases may have overlooked articles that did not include the key search terms in their title, abstract, or keywords. Despite attempts to be as comprehensive as possible, not all studies on teacher effectiveness may have been identified in this review.

Conclusions

In this review, we presented the results of a systematic review of the peer-reviewed and published literature on teacher effectiveness in HE. Teacher effectiveness should broadly encompass competence in four areas (teaching style, course organization, student engagement, and determination of progress). This review represents a first step toward understanding evidence-based practices in teaching.

It is important to note, however, that the summary themes of practice do not contain an exhaustive list of all possible practices of teachers. Instead, the themes embody the most important practices related to implementing teacher effectiveness.

While many of the instruments promoted a comprehensive analysis of effectiveness using multiple methods of data collection, many of them did not take into account the contextual nature of instruction. Some of the instruments recommended other data collection techniques for assessing the overall quality of effectiveness to be used in conjunction with observation techniques.

Nevertheless, additional research is needed to assess teacher effectiveness along with student perceptions of effectiveness and expectations for an effective classroom climate. In this way, scholars and education stakeholders can gain a better understanding of effective teaching practices and how they relate to the evaluations of higher education's most important consumers, the students.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SM conceived and designed the study. SM and CL performed the literature search and study selection process. SM, CL, AK, VD, and EK performed the final analysis process. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was funded by Microkosmos, Italo-Hellenic Cultural Association for Education.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

* Åkerlind, G. S (2004). A new dimension to understanding University teaching. Teach. Higher Educ. 9, 363–375. doi: 10.1080/1356251042000216679

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Altbach, P. G., Reisberg, L., and Rumbley, L. E. (2009). Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution . Paris: UNESCO.

Google Scholar

Andersen, B. L., Jørnø, R. L., and Nortvig, A. M. (2021). Blending adaptive learning technology into nursing education: a scoping review. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 14, ep333. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/11370

Anderson, S., Allen, P., Peckham, S., and Goodwin, N. (2008). Asking the right questions: Scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res. Policy Syst. 6, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Atkins, M., and Brown, G. (2002). Effective Teaching in Higher Education . New York, NY: Routledge.

Bassey, B. A., Owan, V. J., and Agunwa, J. N. (2019). Quality assurance practices and students' performance evaluation in universities of South-South Nigeria: A structural equation modelling approach. Br. J. Psychol. Res. 7, 1–13. Available online at: https://philarchive.org/rec/BASQAP?how_to_cite=1

Bates, A. W., and Poole, G. (2003). Effective Teaching With Technology in Higher Education: Foundations for Success. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

* Berk, R. A (2005). Survey of 12 strategies to measure teaching effectiveness. International J. Teach. Learn. Higher Educ. 17, 48–62.

* Bidabadi, N. S., Isfahani, A. N., Rouhollahi, A., and Khalili, R. (2016). Effective teaching methods in higher education: requirements and barriers. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Profession. 4, 170.

Biggs, J. B (1987). Study Process Questionnaire Manual. Student Approaches to Learning and Studying . Hawthorn: Australian Council for Educational Research Ltd.

Campbell, R. J., Kyriakides, L., Muijs, R. D., and Robinson, W. (2004). Differential Teacher Effectiveness: towards a model for research and teacher appraisal. Oxford Rev. Educ. 29, 347–362. doi: 10.1080/03054980307440

Cardoso, S., Tavares, O., and Sin, C. (2015). The quality of teaching staff: higher education institutions' compliance with the European Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance: The case of Portugal. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 27, 205–222. doi: 10.1007/s11092-015-9211-z

Cheng, Y. C., and Tsui, K. T. (1999). Multimodels of teacher effectiveness: Implications for research. J. Educ. Res. 92, 141–150. doi: 10.1080/00220679909597589

* Coffey, M., and Gibbs, G. (2002). Measuring teachers' repertoire of teaching methods. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 27, 383–390. doi: 10.1080/0260293022000001382

Cohen, P. A (1981). Student ratings of instruction and student achievement: a meta-analysis of multisection validity studies. Rev. Educ. Res. 51, 281–309. doi: 10.3102/00346543051003281

Cruickshank, D. R., and Haefele, D. L. (1990). based indicators: Is the glass half-full or half-empty?. J. Personnel Eval. Educ. 4, 33–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00177128

* Dall'Alba, G (1991). Foreshadowing conceptions of teaching. Res. Dev. Higher Educ. 13, 293–297.

Daudt, H., van Mossel, C., and Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med. Res. 13, 48–56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

Davis, K., Drey, N., and Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 46, 1386–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010

Devlin, M (2007). “Improving teaching in tertiary education: Institutional and individual influences,” in Excellence in Education and Training Convention (2007). Singapore: Singapore Polytechnic.

* Devlin, M., and Samarawickrema, G. (2010). The criteria of effective teaching in a changing higher education context. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 29, 111–124. doi: 10.1080/07294360903244398

Diao, X., Kweka, J., McMillan, M., and Qureshi, Z. (2020). Economic transformation in Africa from the bottom up: New evidence from Tanzania. World Bank Econ. Rev. 34(Supplement_1), S58–S62. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhz035

Dill, D. D., and Van Vught, F. A. (2010). National Innovation and the Academic Research Enterprise: Public Policy in Global Perspective. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ding, C., and Sherman, H. (2006). Teaching effectiveness and student achievement: examining the relationship. Educ. Res. Q. 29, 40–51.

* Dunkin, M. J (1990). The induction of academic staff to a University: processes and products. Higher Educ. 20, 47–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00162204

Dynarski, M (2008). Comments on Slavin: Bringing answers to educators: guiding principles for research syntheses. Educ. Res. 37, 27–29. doi: 10.3102/0013189X08315011

Egan, A., Maguire, R., Christophers, L., and Rooney, B. (2017). Developing creativity in higher education for 21st century learners: a protocol for a scoping review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 82, 21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2016.12.004

Engel-Yeger, B., Tse, T., Josman, N., Baum, C., and Carey, L. M. (2018). Scoping review: the trajectory of recovery of participation outcomes following stroke. Behav. Neurol. 2018, 5472018–5472018. doi: 10.1155/2018/5472018

Entwistle, N (2009). Universities into the 21st Century: Teaching for Understanding at University: Deep Approaches and Distinctive Ways of Thinking . Available online at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Universities-into-the-21st-Century%3A-Teaching-for-at-Entwistle/5ed70e26bc8e55b46f316080d80bed321825722f

Entwistle, N (2018). Student Learning and Academic Understanding: A Research Perspective With Implications for Teaching . New York and London: Elsevier.

Entwistle, N., and Karagiannopoulou, E. (2014). “Perceptions of assessment and their influences on learning,” in Advances and Innovations in Assessment and Feedback , eds C. Kreber, C. Anderson, N. Entwistle, and I. McArthur (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 75–98.

* Entwistle, N., and Walker, P. (2002). “Strategic alertness and expanded awareness within sophisticated conceptions of teaching,” in Teacher Thinking, Beliefs and Knowledge in Higher Education (Berlin: Springer), 15–39.

Fenstermacher, G. D., and Richardson, V. (2005). On making determinations of quality in teaching. Teach. Coll. Rec. 107, 186–213. doi: 10.1177/016146810510700113

Fraser, B. J., Aldridge, J. M., and Soerjaningsih, W. (2010). Instructor-student interpersonal interaction and student outcomes at the University level in Indonesia. Open Educ. J. 3, 10021. doi: 10.2174/1874920801003010021

Fry, H., Ketteridge, S., and Marshall, S., (eds.). (2008). A Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Enhancing Academic Practice. New York: Routledge.

Gibbs, G., and Coffey, M. (2004). The impact of training of University teachers on their teaching skills, their approach to teaching and the approach to learning of their students. Active Learn. Higher Educ. 5, 87–100. doi: 10.1177/1469787404040463

Gibbs, G., and Jenkins, A. (2014). Teaching Large Classes in Higher Education: How to Maintain Quality With Reduced Resources. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gill, S., and Singh, G. (2020). Developing inclusive and quality learning environments in HEIs. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 34, 823–836. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-03-2019-0106

Glasper, A., and Carpenter, D., (eds.). (2021). How to Write Your Nursing Dissertation . New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Goe, L., Bell, C., and Little, O. (2008). Approaches to Evaluating Teacher Effectiveness: A Research Synthesis . Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

* Gow, L., and Kember, D. (1993). Conceptions of teaching and their relationship to student learning. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 63, 20–23. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1993.tb01039.x

Hariharasudan, A., and Kot, S. (2018). A scoping review on Digital English and Education 4.0 for Industry 4.0. Soc. Sci. 7, 227. doi: 10.3390/socsci7110227

Henard, F., and Roseveare, D. (2012). “Fostering quality teaching in higher education: policies and practices,” in An IMHE Guide for Higher Education Institutions , 7–11.

Hoidn, S., Reusser, K., and Klemenčič, M. (2021). “Foundations of student-centered learning and teaching,” Routledge International Handbook of Student-Centered Learning and Teaching in Higher Education , 17–46.

Johnson, T. D., and Ryan, K. E. (2000). A comprehensive approach to the evaluation of college teaching. New Direct. Teach. Learn. 2000, 109–123. doi: 10.1002/tl.8309

Karagiannopoulou, E., and Christodoulides, P. (2005). The impact of Greek University students' perceptions of their learning environment on approaches to studying and academic outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 43, 329–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2006.05.002

Karagiannopoulou, E., and Entwistle, N. (2013). Influences on personal understanding: approaches to learning, perceptions of assessment, and the “meeting of minds”. Psychol. Teach. Rev. 13, 80–96. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1149736.pdf

Karagiannopoulou, E., and Entwistle, N. (2019). Students' learning characteristics, perceptions of small-group University teaching, and understanding through a “meeting of minds”. Front. Psychol. 10, 444. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00444

Karagiannopoulou, E., and Milienos, F. S. (2013). Exploring the relationship between experienced students' preference for open-and closed-book examinations, approaches to learning and achievement. Educ. Res. Eval. 19, 271–296. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2013.765691

Karagiannopoulou, E., and Milienos, F. S. (2015). Testing two path models to explore relationships between students' experiences of the teaching–learning environment, approaches to learning and academic achievement. Educ. Psychol. 35, 26–52. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2014.895800

Kember, D (1997). A reconceptualisation of the research into University academics' conceptions of teaching. Learn. Instruct. 7, 255–275. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00028-X

Kember, D (1998). Teaching beliefs and their impact on students' approach to learning. Teach. Learn. Higher Educ. 4, 1–25.

Kember, D., and Gow, L. (1994). Orientations to teaching and their effect on the quality of student learning. J. Higher Educ. 65, 58–74. doi: 10.2307/2943877

* Kember, D., and Kwan, K. P. (2000). Lecturers' approaches to teaching and their relationship to conceptions of good teaching. Instruct. Sci. 28, 469–490. doi: 10.1023/A:1026569608656

Khandan, R., and Shannon, L. (2021). The effect of teaching–learning environments on student's engagement with lean mindset. Educ. Sci. 11, 466. doi: 10.3390/educsci11090466

Laurillard, D (2002). Rethinking University Teaching: A Conversational Framework for the Effective Use of Learning Technologies. New York: Routledge.

Leiber, T (2018). Impact evaluation of quality management in higher education: a contribution to sustainable quality development in knowledge societies. Eur. J. Higher Educ. 8, 235–248. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2018.1474775

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., and O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 5, 69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Marsh, H. W (1984). Students' evaluations of University teaching: dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential biases, and utility. J. Educ. Psychol. 76,707–754. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.76.5.707

* Martin, E., Prosser, M., Trigwell, K., Ramsden, P., and Benjamin, J. (2002). “What University teachers teach and how they teach it,” in Teacher Thinking, Beliefs and Knowledge in Higher Education . Berlin: Springer.

Martin, N. K., and Shoho, A. R. (2002). “Teacher experience, training, & age: The influence of teacher characteristics on classroom management style,” in What University Teachers Teach and How They Teach It: In Teacher Thinking, Beliefs and Knowledge in Higher Education , eds E. Martin, M. Prosser, K. Trigwell, P. Ramsden, and J. Benjamin(Dordrecht: Springer), 103—126.

* Mbalamula, Y. S (2017). Complementing lecturing as teaching pedagogy and students learning styles in universities in Tanzania: State of issues. Educ. Res. Rev. 12, 653–659. doi: 10.5897/ERR2017.3232

McBean, E. A., and Al-Nassri, S. (1982). Questionnaire design for student measurement of teaching effectiveness. Higher Educ. 11, 273–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00155619

* McMillan, W. J (2007). ‘Then you get a teacher': Guidelines for excellence in teaching. Med. Teacher 29, e209–e218. doi: 10.1080/01421590701478264

Milienos, F. S., Rentzios, C., Catrysse, L., Gijbels, D., Mastrokoukou, S., Longobardi, C., et al. (2021). The contribution of learning and mental health variables in first-year students' profiles. Front. Psychol. 12, 1259. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627118

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Muijs, D (2006). Measuring teacher effectiveness: Some methodological reflections. Educ. Res. Eval. 12, 53–74. doi: 10.1080/13803610500392236

* Murray, K., and Macdonald, R. (1997). The disjunction between lecturers' conceptions of teaching and their claimed educational practice. Higher Educ. 33, 331–349. doi: 10.1023/A:1002931104852

* Norton, L., Richardson, T. E., Hartley, J., Newstead, S., and Mayes, J. (2005). Teachers' beliefs and intentions concerning teaching in higher education. Higher Educ. 50, 537–571. doi: 10.1007/s10734-004-6363-z

Okoli, C (2019). Developing Theory from Literature Reviews with Theoretical Concept Synthesis: Topical, Propositional and Confirmatory Approaches . Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3452134 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3452134

Partee, G. L (2012). Using Multiple Evaluation Measures to Improve Teacher Effectiveness: State Strategies From Round 2 of No Child Left Behind Act Waivers . Center for American Progress.

* Paulsen, M. B (2002). Evaluating teaching performance. New Direct. Inst. Res. 2002, 5–18. doi: 10.1002/ir.42

Pratt, D. D (1998). Five Perspectives on Teaching in Adult and Higher Education . Krieger: Krieger Publishing Co.

Prosser, M., Martin, E., and Trigwell, K. (2007). “4 Academics' experiences of teaching and of their subject matter understanding,” in BJEP Monograph Series II, Number 4-Student Learning and University Teaching (Scotland: British Psychological Society), 49–59.

Prosser, M., and Trigwell, K. (1999). Understanding Learning and Teaching: The Experience in Higher Education . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

* Qureshi, S., and Ullah, R. (2014). Learning experiences of higher education students: approaches to learning as measures of quality of learning outcomes. Bull. Educ. Res. 36, 79–100. Available online at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Learning-Experiences-of-Higher-Education-Students%3A-Qureshi-Ullah/901e743718cd6193fe5c2fcde4b30c810fe6cedf#citing-papers

* Ramsden, P (1991). A performance indicator of teaching quality in higher education: The Course Experience Questionnaire. Stud. Higher Educ. 16, 129–150. doi: 10.1080/03075079112331382944

Richardson, J. T (2017). Student learning in higher education: a commentary. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 29, 353–362. doi: 10.1007/s10648-017-9410-x

Richardson, P. W., and Watt, H. M. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia-Pacific J. Teach. Educ. 34, 27–56. doi: 10.1080/13598660500480290

* Samuelowicz, K., and Bain, J. D. (1992). Conceptions of teaching held by academic teachers. Higher Educ. 24, 93–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00138620

* Samuelowicz, K., and Bain, J. D. (2001). Revisiting academics' beliefs about teaching and learning. Higher Educ. 41, 299–325. doi: 10.1023/A:1004130031247

* Sander, P., Stevenson, K., King, M., and Coates, D. (2000). University students' expectations of teaching. Stud. Higher Educ. 25, 309–323. doi: 10.1080/03075070050193433

* Shao, L. P., Anderson, L. P., and Newsome, M. (2007). Evaluating teaching effectiveness: where we are and where we should be. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 32, 355–371. doi: 10.1080/02602930600801886

Sibgatullin, I. R., Korzhuev, A. V., Khairullina, E. R., Sadykova, A. R., Baturina, R. V., and Chauzova, V. (2022). A systematic review on algebraic thinking in education. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 18, em2065. doi: 10.29333/ejmste/11486

Tadesse, E. F., and Khalid, S. (2022). Are teachers and HE are on the same page? Calling for a research–teaching nexus among Ethiopian and Pakistani academics. J. Appl. Res. Higher Educ. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-09-2021-0348 [Epub ahead of print].

Theall, M., and Franklin, J. (2001). Looking for bias in all the wrong places: a search for truth or a witch hunt in student ratings of instruction? New Direct. Inst. Res. 2001, 45–56. doi: 10.1002/ir.3

Trigwell, K (2001). Judging University teaching. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 6, 65–73. doi: 10.1080/13601440110033698

* Trigwell, K., and Prosser, M. (1993). Approaches adopted by teachers of first year University science courses. Res. Dev. Higher Educ. 14, 223–228.

* Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., and Waterhouse, F. (1999). Relations between teachers' approaches to teaching and students' approaches to learning. Higher Educ. 37, 57–70. doi: 10.1023/A:1003548313194

Vermunt, J. D., and Donche, V. (2017). A learning patterns perspective on student learning in higher education: State of the art and moving forward. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 29, 269–299. doi: 10.1007/s10648-017-9414-6

* Vulcano, B. A (2007). Extending the generality of the qualities and behaviors constituting effective teaching. Teach. Psychol. 34, 114–117. doi: 10.1177/009862830703400210

* Willcoxson, L (1998). The impact of academics' learning and teaching preferences on their teaching practices: a pilot study. Stud. Higher Educ. 23, 59–70. doi: 10.1080/03075079812331380492

Yorke, M (2003). Formative assessment in higher education: moves towards theory and the enhancement of pedagogic practice. Higher Educ. 45, 477–501. doi: 10.1023/A:1023967026413

Zhang, L. F., and Sternberg, R. J. (2002). Thinking styles and teachers' characteristics. Int. J. Psychol. 37, 3–12. doi: 10.1080/00207590143000171

Zuñiga, P., Navarro, J. C., and Llisterri, C. (2010). ”The importance of ideas: Innovation and productivity in Latin America,” in The Age of Productivity: Transforming Economies From the Bottom Up. Development in the Americas Report , eds C. Pagés (Inter-American Development Bank/Palgrave-McMillan), 223–255.

Keywords: teacher effectiveness, higher education institutions, undergraduate students, scoping review, teacher student interaction

Citation: Mastrokoukou S, Kaliris A, Donche V, Chauliac M, Karagiannopoulou E, Christodoulides P and Longobardi C (2022) Rediscovering Teaching in University: A Scoping Review of Teacher Effectiveness in Higher Education. Front. Educ. 7:861458. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.861458

Received: 24 January 2022; Accepted: 28 February 2022; Published: 28 March 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Mastrokoukou, Kaliris, Donche, Chauliac, Karagiannopoulou, Christodoulides and Longobardi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claudio Longobardi, claudio.longobardi@unito.it

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

Introduction, purposes of teacher evaluation.

- International Policy and Research Reports

- US Policy and Research Reports

- Textbooks on Teacher Effectiveness and Teacher Evaluation

- Early Models of Teacher Evaluation

- Contemporary Models of Teacher Evaluation

- Measuring Teacher Effectiveness

- Value-Added Models in Teacher Evaluation

- Teacher Observation in Teacher Evaluation

- Impacts of Teacher Evaluation on Teacher Quality

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- A Pedagogy of Teacher Education

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Black Women in Academia

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- History of Education in Europe

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness by James H. Stronge , Leslie W. Grant , Xianxuan Xu LAST REVIEWED: 28 July 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 28 July 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0138

Teacher evaluation has evolved over time from focusing on the moral values of a teacher in the early 1900s to standards-based evaluation models of today that seek to include measures of student academic progress. Often, teacher evaluation systems seek to serve two needs: accountability and improvement. Changes in teacher evaluation have been influenced by political winds as well as a desire to create systems that are fair and balanced. This article begins with an overview of the purposes of teacher evaluation. Next, often-cited international and US policy and research reports as well as foundational textbooks related to teacher effectiveness and teacher evaluation are highlighted. The article then provides an overview of early models of teacher evaluation focused on the roles and responsibilities of a teacher and the evolution to contemporary models of teacher evaluation with a focus on a standards-based and/or outcomes-based approach to evaluation. The next section highlights seminal works that emerged in measuring teacher effectiveness as well as value-added models to support an outcomes-based approach by including student academic progress as part of evaluation. Including student outcomes has been the topic of intense discussion as policymakers and researchers debate the validity of the use of student test scores in terms of value-added modeling and other growth models. Researchers do not agree on the stability of such models and whether they do differentiate between effective and less effective teachers. Research will continue to inform and enrich this debate and discussion. Teacher observation remains a critical part of the evaluation process and the article provides a historical overview of common practices and challenges of teacher observation. Finally, works that illuminate impacts of teacher evaluation are provided, including texts and reports related to teacher growth and development, teacher retention, and teacher compensation.

Teacher evaluation that is intended to be productive and actionable must address either teacher growth and support, the quality of teacher performance, or both. In essence, teacher evaluation can and should consider purposes for helping teachers improve their performance as well as providing accountable for their work. While other teacher evaluation purposes are identified periodically (e.g., school improvement), the most commonly accepted purposes for teacher evaluation are: (1) supporting teacher personal and professional growth that leads to improved and sustained quality performance, and (2) documenting results of teaching practices for reporting and accountability. There is considerable discussion and little agreement in the extant literature regarding whether both purposes can and should be achieved within the same performance evaluation system. One point of agreement is that regardless of the purpose— teacher professional growth or teacher accountability—the intended purpose(s) of teacher evaluation must be actionable if evaluation is to a worthwhile endeavor. Earlier publications— Peterson 2000 , Gordon 2006 , and Stronge 2006 —posit the rationale for a connection among evaluation of teacher performance, teacher growth and development, and school improvement. A case for using evaluation for the purpose of accountability, or teacher dismissal, more specifically, is made in Chait 2010 . A case for using evaluation for the purposes of teacher development is described in Donaldson and Peske 2010 . Crowe 2010 argues that the first evaluation of a teacher occurs in her teacher education program and that we should have a strong accountability system for teacher education programs to make sure the graduates have the knowledge and skills to be effective with students. Huber and Skedsmo 2016 frames the primary purposes of teacher evaluation as formative (teacher growth and support) and summative (teacher accountability). A report from the National Council on Teacher Quality, Gerber 2019 advocates for teacher evaluation designs that help teachers improve their practice and support distribution of teacher quality equitably across schools.

Chait, Robin. 2010. Removing chronically ineffective teachers: Barriers and opportunities . Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Chait recognizes that teachers have a tremendous impact on student achievement and that teachers vary greatly in their effectiveness. This report focuses on one critical piece in the human capital systems in school—the dismissal of chronically ineffective teachers. The challenges in removing teachers who are persistently ineffective and fail to improve even with intensive support over time are described.

Crowe, Edward. 2010. Measuring what matters: A stronger accountability model for teacher education . Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Crowe extends the argument of accountability and teacher evaluation into the sector of teacher preparation. He maintains that teacher education programs should serve as a real quality control and use empirically based indicators to measure the extent to which graduates help their students learn.

Donaldson, Morgaen L., and Heather G. Peske. 2010. Supporting effective teaching through teacher evaluation: A study of teacher evaluation in five charter schools . Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

This text reports findings from a study of teacher evaluation practices in five charter schools. The authors find that a rigorous teacher evaluation system can influence teachers’ instructional capabilities in a positive way.