How to Write an Interpretive Essay?

An essay is one of the most common types of tasks assigned to students in high school and college. If you are wondering why instructors give you this writing project once you’ve just finished with a previous one, keep reading the article!

Why interpretive essays are assigned so often? First of all, such tasks reflect your thinking, so teachers can see whether you understand key concepts and theories in their discipline. In fact, it’s impossible to fake your knowledge with random information because experienced instructors can easily notice it. Secondly, essays are considered better assessment tools than tests.

Why so? Probably, because it’s impossible to guess answers or find clues. Also, essays demonstrate a wide set of skills you’ve gained in class. Alongside your understanding of a certain discipline, an essay paper indicates how you can make research, organize your thoughts, and provide arguments.

What is an interpretive essay?

An interpretive essay is a type of writing often required in subjects like English, history, literature, philosophy, and religion. In this essay, you are expected to critically think about a topic and then present your ideas to readers in a way that can be either objective or subjective, depending on the assignment’s requirements.

If you are looking for the most comprehensive interpretive essay definition, here it is: an interpretive essay is a piece of writing that identifies, evaluates, and analyzes the methods used by the author in a particular work. The interpretation answers the questions like ‘What were the main characters and events?’, ‘What tone was used by the author?’, ‘Where was the setting?’, and so on.

An interpretive essay is a piece of writing that identifies, evaluates, and analyzes the methods used by the author in a particular work.

The key focus of an interpretive essay is on your personal feelings, analysis, and presentation of a subject. It involves making a case for your ideas, aiming to be informative and persuasive, while also keeping the writing interesting. This form of writing is distinctly personal, reflecting your views, arguments, and subjective opinions.

This type of assignment allows you to provide any opinion about a piece of writing as long as you can support it. In fact, there is no “right or wrong” answer because it’s all about explaining your thoughts about the piece. An interpretive essay requires profound knowledge and genuine interest in the writing piece you’ve chosen. You also need to make thorough research of the subject to provide a defendable interpretation and build it logically.

The effectiveness of an interpretive essay depends on how well you can persuade and critically engage with the subject, which is influenced by the specific guidelines of the assignment. Understanding the purpose of your writing and who your audience is plays a crucial role in crafting an effective interpretive essay. Additionally, it’s important to be aware of your instructor’s expectations and be familiar with different writing formats. If you’re ever uncertain, it’s advisable to ask questions and use available resources like a reading writing center.

How to write an interpretive essay?

Before you start writing an interpretive essay, read the poem, story, or novel chapter you were assigned a few times. While reading, highlight various literary elements like symbols, character descriptions, activities, settings, etc. Then write down those of them that you are going to interpret. Once you have a full list of literary elements to analyze, you can move to the introduction. Let’s consider in detail how to write it.

1️⃣ Introduction

Start your introduction with a short summary of the piece. Write it in 3-4 sentences, so the reader can get familiar with the content. You shouldn’t give your opinion about it, just summarize the work. Don’t forget to mention the full title of the writing piece, the author’s name and the literary elements you will interpret in body paragraphs. Then come up with your thesis statement in one sentence.

The essay body is the part where you have to do your analysis by stating what you think the text is about. Note that your opinion must be supported with relevant examples, so add quotations and paraphrases to your arguments. If you provide some ideas about patterns, symbols and themes, make sure you can back up each of them.

Analyzing literary elements requires you to explain their meaning, compare them and contrast them with each other. Your teacher will also appreciate it if you apply a literary theory to each element. Basically, logical analysis with the right structure will definitely bring you the highest grade.

It’s really important to organize your paragraphs in order of the elements you are going to interpret. Start each of them with a statement to create the roadmap for your readers.

Generally, every paragraph must include a particular idea answering the questions like:

- “What do you think about…?”

- “Do you agree with…?”

- “Is it true that…?”

as well as supporting arguments and a clear takeaway message.

It would be great to pose implicit questions that engage the reader in reflection. They may sound like “Although the author doesn’t mention it, there is the reason to believe…”, “The idea is very ambiguous, and there’s room for dispute…”, etc.

3️⃣ Conclusion

In conclusion, you have to unify the main literary elements you have interpreted in your essay. In general, this part of your paper summarizes the main points of your analysis. Basically, it must explain how the interpreted piece of writing fits into the big picture of life or literature as well as how it added to your personal growth. You can also make it clear how your analysis could contribute to understanding the society or literature of people who read it.

Some helpful life hacks to help you write an interpretive essay

📌 create a mind map.

One of the most powerful tools to organize your thoughts before writing itself is visualization. You can draw an essay map on paper or use a smartphone app for this purpose. When you see the whole picture of your ideas and the connections between them, it will be much easier to start writing your essay.

📌 Make a list of questions

This action has a similar goal to the previous one, which is basically to guide you while writing. To make your paper properly structured, create a list of questions that must be necessarily answered in your essay. Then rearrange them in the best way possible and start answering one question in each paragraph.

📌 Use a thesaurus

If you check the best interpretive essay examples, you will notice that they have a rich vocabulary. To enhance the wording, use a thesaurus. It will help you to get rid of tautologies across the text, replace some words with more appropriate equivalents, and choose synonyms.

📌 Read your work out loud

To spot imperfections and improve your essay, you should reread it after finishing your work. It would be better to read the text out loud, so you can better understand what thoughts may seem unclear or vague.

Final thoughts

In short, an excellent paper provides a brief summary of the literary work in its introduction, gives a clear interpretation of the author’s message as well as includes details, quotes, and other evidence supporting your interpretation.

Interpretive writing can take various forms, including summaries, analyses, critiques, research papers, and essays. Each of these forms requires a unique approach but shares the common goal of presenting a thoughtful, well-reasoned interpretation of the subject matter.

So if you want to get the highest grade for your essay, make sure to add all the mentioned above to it. Although a solid interpretive essay requires much effort and time, it’s much easier to complete if you follow the tips given above.

The Power of Analysis: Tips and Tricks for Writing Analysis Essays: Home

Crystal sosa.

Helpful Links

- Super Search Webpage Where to start your research.

- Scribbr Textual analysis guide.

- Analyzing Texts Prezi Presentation A prezi presentation on analyzing texts.

- Writing Essays Guide A guide to writing essays/

- Why is it important?

- Explanation & Example

- Different Types of Analysis Essays

Text analysis and writing analysis texts are important skills to develop as they allow individuals to critically engage with written material, understand underlying themes and arguments, and communicate their own ideas in a clear and effective manner. These skills are essential in academic and professional settings, as well as in everyday life, as they enable individuals to evaluate information and make informed decisions.

What is Text Analysis?

Text analysis is the process of examining and interpreting a written or spoken text to understand its meaning, structure, and context. It involves breaking down the text into its constituent parts, such as words, phrases, and sentences, and analyzing how they work together to convey a particular message or idea.

Text analysis can be used to explore a wide range of textual material, including literature, poetry, speeches, and news articles, and it is often employed in academic research, literary criticism, and media analysis. By analyzing texts, we can gain deeper insights into their meanings, uncover hidden messages and themes, and better understand the social and cultural contexts in which they were produced.

What is an Analysis Essay?

An analysis essay is a type of essay that requires the writer to analyze and interpret a particular text or topic. The goal of an analysis essay is to break down the text or topic into smaller parts and examine each part carefully. This allows the writer to make connections between different parts of the text or topic and develop a more comprehensive understanding of it.

In “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman uses the first-person point of view and vivid descriptions of the protagonist’s surroundings to convey the protagonist’s psychological deterioration. By limiting the reader’s understanding of the story’s events to the protagonist’s perspective, Gilman creates a sense of claustrophobia and paranoia, mirroring the protagonist’s own feelings. Additionally, the use of sensory language, such as the “smooch of rain,” and descriptions of the “yellow wallpaper” and its “sprawling flamboyant patterns,” further emphasize the protagonist’s sensory and emotional experience. Through these techniques, Gilman effectively communicates the protagonist’s descent into madness and the effects of societal oppression on women’s mental health.

There are several different types of analysis essays, including:

Literary Analysis Essays: These essays examine a work of literature and analyze various literary devices such as character development, plot, theme, and symbolism.

Rhetorical Analysis Essays: These essays examine how authors use language and rhetoric to persuade their audience, focusing on the author's tone, word choice, and use of rhetorical devices.

Film Analysis Essays: These essays analyze a film's themes, characters, and visual elements, such as cinematography and sound.

Visual Analysis Essays: These essays analyze visual art, such as paintings or sculptures, and explore how the artwork's elements work together to create meaning.

Historical Analysis Essays: These essays analyze historical events or documents and examine their causes, effects, and implications.

Comparative Analysis Essays: These essays compare and contrast two or more works, focusing on similarities and differences between them.

Process Analysis Essays: These essays explain how to do something or how something works, providing a step-by-step analysis of a process.

Analyzing Texts

- General Tips

- How to Analyze

- What to Analyze

When writing an essay, it's essential to analyze your topic thoroughly. Here are some suggestions for analyzing your topic:

Read carefully: Start by reading your text or prompt carefully. Make sure you understand the key points and what the text or prompt is asking you to do.

Analyze the text or topic thoroughly: Analyze the text or topic thoroughly by breaking it down into smaller parts and examining each part carefully. This will help you make connections between different parts of the text or topic and develop a more comprehensive understanding of it.

Identify key concepts: Identify the key concepts, themes, and ideas in the text or prompt. This will help you focus your analysis.

Take notes: Take notes on important details and concepts as you read. This will help you remember what you've read and organize your thoughts.

Consider different perspectives: Consider different perspectives and interpretations of the text or prompt. This can help you create a more well-rounded analysis.

Use evidence: Use evidence from the text or outside sources to support your analysis. This can help you make your argument stronger and more convincing.

Formulate your thesis statement: Based on your analysis of the essay, formulate your thesis statement. This should be a clear and concise statement that summarizes your main argument.

Use clear and concise language: Use clear and concise language to communicate your ideas effectively. Avoid using overly complicated language that may confuse your reader.

Revise and edit: Revise and edit your essay carefully to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors.

- Understanding the assignment: Make sure you fully understand the assignment and the purpose of the analysis. This will help you focus your analysis and ensure that you are meeting the requirements of the assignment.

Read the essay multiple times: Reading the essay multiple times will help you to identify the author's main argument, key points, and supporting evidence.

Take notes: As you read the essay, take notes on key points, quotes, and examples. This will help you to organize your thoughts and identify patterns in the author's argument.

Take breaks: It's important to take breaks while reading academic essays to avoid burnout. Take a break every 20-30 minutes and do something completely different, like going for a walk or listening to music. This can help you to stay refreshed and engaged.

Highlight or underline key points: As you read, highlight or underline key points, arguments, and evidence that stand out to you. This will help you to remember and analyze important information later.

Ask questions: Ask yourself questions as you read to help you engage critically with the text. What is the author's argument? What evidence do they use to support their claims? What are the strengths and weaknesses of their argument?

Engage in active reading: Instead of passively reading, engage in active reading by asking questions, making connections to other readings or personal experiences, and reflecting on what you've read.

Find a discussion partner: Find someone to discuss the essay with, whether it's a classmate, a friend, or a teacher. Discussing the essay can help you to process and analyze the information more deeply, and can also help you to stay engaged.

- Identify the author's purpose and audience: Consider why the author wrote the essay and who their intended audience is. This will help you to better understand the author's perspective and the purpose of their argument.

Analyze the structure of the essay: Consider how the essay is structured and how this supports the author's argument. Look for patterns in the organization of ideas and the use of transitions.

Evaluate the author's use of evidence: Evaluate the author's use of evidence and how it supports their argument. Consider whether the evidence is credible, relevant, and sufficient to support the author's claims.

Consider the author's tone and style: Consider the author's tone and style and how it contributes to their argument. Look for patterns in the use of language, imagery, and rhetorical devices.

Consider the context : Consider the context in which the essay was written, such as the author's background, the time period, and any societal or cultural factors that may have influenced their perspective.

Evaluate the evidence: Evaluate the evidence presented in the essay and consider whether it is sufficient to support the author's argument. Look for any biases or assumptions that may be present in the evidence.

Consider alternative viewpoints: Consider alternative viewpoints and arguments that may challenge the author's perspective. This can help you to engage critically with the text and develop a more well-rounded understanding of the topic.

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2023 1:01 PM

- URL: https://odessa.libguides.com/analysis

How To Write an Analytical Essay

If you enjoy exploring topics deeply and thinking creatively, analytical essays could be perfect for you. They involve thorough analysis and clever writing techniques to gain fresh perspectives and deepen your understanding of the subject. In this article, our expert research paper writer will explain what an analytical essay is, how to structure it effectively and provide practical examples. This guide covers all the essentials for your writing success!

What Is an Analytical Essay

An analytical essay involves analyzing something, such as a book, movie, or idea. It relies on evidence from the text to logically support arguments, avoiding emotional appeals or personal stories. Unlike persuasive essays, which argue for a specific viewpoint, a good analytical essay explores all aspects of the topic, considering different perspectives, dissecting arguments, and evaluating evidence carefully. Ultimately, you'll need to present your own stance based on your analysis, synthesize findings, and decide whether you agree with the conclusions or have your own interpretation.

Wondering How to Impress Your Professor with Your Essay?

Let our writers craft you a winning essay, no matter the subject, field, type, or length!

How to Structure an Analytical Essay

Crafting an excellent paper starts with clear organization and structuring of arguments. An analytical essay structure follows a simple outline: introduction, body, and conclusion.

Introduction: Begin by grabbing the reader's attention and stating the topic clearly. Provide background information, state the purpose of the paper, and hint at the arguments you'll make. The opening sentence should be engaging, such as a surprising fact or a thought-provoking question. Then, present your thesis, summarizing your stance in the essay.

Body Paragraphs: Each paragraph starts with a clear topic sentence guiding the reader and presents evidence supporting the thesis. Focus on one issue per paragraph and briefly restate the main point at the end to transition smoothly to the next one. This ensures clarity and coherence in your argument.

Conclusion: Restate the thesis, summarize key points from the body paragraphs, and offer insights on the significance of the analysis. Provide your thoughts on the topic's importance and how your analysis contributes to it, leaving a lasting impression on the reader.

Meanwhile, you might also be interested in how to write a reflection paper , so check out the article for more information!

How to Write an Analytical Essay in 6 Simple Steps

Once you've got a handle on the structure, you can make writing easier by following some steps. Preparing ahead of time can make the process smoother and improve your essay's flow. Here are some helpful tips from our experts. And if you need it, you can always request our experts to write my essay for me , and we'll handle it promptly.

.webp)

Step 1: Decide on Your Stance

Before diving into writing, it's crucial to establish your stance on the topic. Let's say you're going to write an analytical essay example about the benefits and drawbacks of remote work. Before you start writing, you need to decide what your opinion or viewpoint is on this topic.

- Do you think remote work offers flexibility and improved work-life balance for employees?

- Or maybe you believe it can lead to feelings of isolation and decreased productivity?

Once you've determined your stance on remote work, it's essential to consider the evidence and arguments supporting your position. Are there statistics or studies that back up your viewpoint? For example, if you believe remote work improves productivity, you might cite research showing increased output among remote workers. On the other hand, if you think it leads to isolation, you could reference surveys or testimonials highlighting the challenges of remote collaboration. Your opinion will shape how you write your essay, so take some time to think about what you believe about remote work before you start writing.

Step 2: Write Your Thesis Statement

Once you've figured out what you think about the topic, it's time to write your thesis statement. This statement is like the main idea or argument of your essay.

If you believe that remote work offers significant benefits, your thesis statement might be: 'Remote work presents an opportunity for increased flexibility and work-life balance, benefiting employees and employers alike in today's interconnected world.'

Alternatively, if you believe that remote work has notable drawbacks, your thesis statement might be: 'While remote work offers flexibility, it can also lead to feelings of isolation and challenges in collaboration, necessitating a balanced approach to its implementation.'

Your thesis statement guides the rest of your analytical essay, so make sure it clearly expresses your viewpoint on the benefits and drawbacks of remote work.

Step 3: Write Topic Sentences

After you have your thesis statement about the benefits and drawbacks of remote work, you need to come up with topic sentences for each paragraph while writing an analytical essay. These sentences introduce the main point of each paragraph and help to structure your essay.

Let's say your first paragraph is about the benefits of remote work. Your topic sentence might be: 'Remote work offers employees increased flexibility and autonomy, enabling them to better manage their work-life balance.'

For the next paragraph discussing the drawbacks of remote work, your topic sentence could be: 'However, remote work can also lead to feelings of isolation and difficulties in communication and collaboration with colleagues.'

And for the paragraph about potential solutions to the challenges of remote work, your topic sentence might be: 'To mitigate the drawbacks of remote work, companies can implement strategies such as regular check-ins, virtual team-building activities, and flexible work arrangements.'

Each topic sentence should relate back to your thesis statement about the benefits and drawbacks of remote work and provide a clear focus for the paragraph that follows.

Step 4: Create an Outline

Now that you have your thesis statement and topic sentences, it's time to create an analytical essay outline to ensure your essay flows logically. Here's an outline prepared by our analytical essay writer based on the example of discussing the benefits and drawbacks of remote work:

Step 5: Write Your First Draft

Now that you have your outline, it's time to start writing your first draft. Begin by expanding upon each point in your outline, making sure to connect your ideas smoothly and logically. Don't worry too much about perfection at this stage; the goal is to get your ideas down on paper. You can always revise and polish your draft later.

As you write, keep referring back to your thesis statement to ensure that your arguments align with your main argument. Additionally, make sure each paragraph flows naturally into the next, maintaining coherence throughout your essay.

Once you've completed your first draft, take a break and then come back to review and revise it. Look for areas where you can strengthen your arguments, clarify your points, and improve the overall structure and flow of your essay.

Remember, writing is a process, and it's okay to go through multiple drafts before you're satisfied with the final result. Take your time and be patient with yourself as you work towards creating a well-crafted essay on the benefits and drawbacks of remote work.

Step 6: Revise and Proofread

Once you've completed your first draft, it's essential to revise and proofread your essay to ensure clarity, coherence, and correctness. Here's how to approach this step:

- Check if your ideas make sense and if they support your main point.

- Make sure your writing style stays the same and your format follows the rules.

- Double-check your facts and make sure you've covered everything important.

- Cut out any extra words and make your sentences clear and short.

- Look for mistakes in spelling and grammar.

- Ask someone to read your essay and give you feedback.

What is the Purpose of an Analytical Essay?

Analytical essays aim to analyze texts or topics, presenting a clear argument. They deepen understanding by evaluating evidence and uncovering underlying meanings. These essays promote critical thinking, challenging readers to consider different viewpoints.

They're also great for improving critical thinking skills. By breaking down complex ideas and presenting them clearly, they encourage readers to think for themselves and reach their own conclusions.

This type of essay also adds to academic discussions by offering fresh insights. By analyzing existing research and literature, they bring new perspectives or shine a light on overlooked parts of a topic. This keeps academic conversations lively and encourages more exploration in the field.

Analytical Essay Examples

Check out our essay samples to see theory in action. Crafted by our dissertation services , they show how analytical thinking applies to real situations, helping you understand concepts better.

With our tips on how to write an analytical essay, you're ready to boost your writing skills and craft essays that captivate your audience. With practice, you'll become a pro at analytical writing, ready to tackle any topic with confidence. And, if you need help to buy essay online , just drop us a line saying ' do my homework for me ' and we'll jump right in!

Do Analytical Essays Tend to Intimidate You?

Give us your assignment to uncover a deeper understanding of your chosen analytical essay topic!

How to Write an Analytical Essay?

What is an analytical essay.

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

Developing Deeper Analysis & Insights

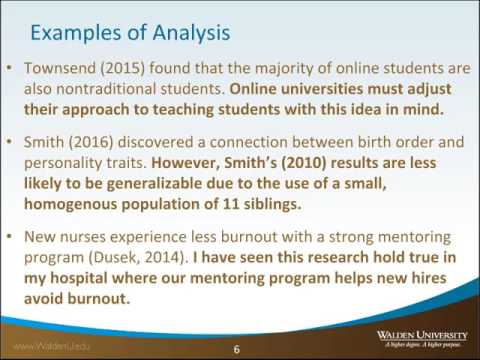

Analysis is a central writing skill in academic writing. Essentially, analysis is what writers do with evidence to make meaning of it. While there are specific disciplinary types of analysis (e.g., rhetorical, discourse, close reading, etc.), most analysis involves zooming into evidence to understand how the specific parts work and how their specific function might relate to a larger whole. That is, we usually need to zoom into the details and then reflect on the larger picture. In this writing guide, we cover analysis basics briefly and then offer some strategies for deepening your analysis. Deepening your analysis means pushing your thinking further, developing a more insightful and interesting answer to the “so what?” question, and elevating your writing.

Analysis Basics

Questions to Ask of the Text:

- Is the evidence fully explained and contextualized? Where in the text/story does this evidence come from (briefly)? What do you think the literal meaning of the quote/evidence is and why? Why did you select this particular evidence?

- Are you selecting a long enough quote to work with and analyze? While over-quoting can be a problem, so too can under-quoting.

- Do you connect each piece of evidence explicitly to the claim or focus of the paper?

Strategies & Explanation

- Sometimes turning the focus of the paper into a question can really help someone to figure out how to work with evidence. All evidence should answer the question--the work of analysis is explaining how it answers the question.

- The goal of evidence in analytical writing is not just to prove that X exists or is true, but rather to show something interesting about it--to push ideas forward, to offer insights about a quote. To do this, sometimes having a full sentence for a quote helps--if a writer is only using single-word quotes, for example, they may struggle to make meaning out of it.

Deepening Analysis

Not all of these strategies work every time, but usually employing one of them is enough to really help elevate the ideas and intellectual work of a paper:

- Bring the very best point in each paragraph into the topic sentence. Often these sentences are at the very end of a paragraph in a solid draft. When you bring it to the front of the paragraph, you then need to read the paragraph with the new topic sentence and reflect on: what else can we say about this evidence? What else can it show us about your claim?

- Complicate the point by adding contrasting information, a different perspective, or by naming something that doesn’t fit. Often we’re taught that evidence needs to prove our thesis. But, richer ideas emerge from conflict, from difference, from complications. In a compare and contrast essay, this point is very easy to see--we get somewhere further when we consider how two things are different. In an analysis of a single text, we might look at a single piece of evidence and consider: how could this choice the writer made here be different? What other choices could the writer have made and why didn’t they? Sometimes naming what isn’t in the text can help emphasize the importance of a particular choice.

- Shift the focus question of the essay and ask the new question of each piece of evidence. For example, a student is looking at examples of language discrimination (their evidence) in order to make an argument that answers the question: what is language discrimination? Questions that are definitional (what is X? How does Y work? What is the problem here?) can make deeper analysis challenging. It’s tempting to simply say the equivalent of “Here is another example of language discrimination.” However, a strategy to help with this is to shift the question a little bit. So perhaps the paragraphs start by naming different instances of language discrimination, but the analysis then tackles questions like: what are the effects of language discrimination? Why is language discrimination so problematic in these cases? Who perpetuates language discrimination and how? In a paper like this, it’s unlikely you can answer all of those questions--but, selecting ONE shifted version of a question that each paragraph can answer, too, helps deepen the analysis and keeps the essay focused.

- Examine perspective--both the writer’s and those of others involved with the issue. You might reflect on your own perspectives as a unique audience/reader. For example, what is illuminated when you read this essay as an engineer? As a person of color? As a first-generation student at Cornell? As an economically privileged person? As a deeply religious Christian? In order to add perspective into the analysis, the writer has to name these perspectives with phrases like: As a religious undergraduate student, I understand X to mean… And then, try to explain how the specificity of your perspective illuminates a different reading or understanding of a term, point, or evidence. You can do this same move by reflecting on who the intended audience of a text is versus who else might be reading it--how does it affect different audiences differently? Might that be relevant to the analysis?

- Qualify claims and/or acknowledge limitations. Before college level writing and often in the media, there is a belief that qualifications and/or acknowledging the limitations of a point adds weakness to an argument. However, this actually adds depth, honesty, and nuance to ideas. It allows you to develop more thoughtful and more accurate ideas. The questions to ask to help foster this include: Is this always true? When is it not true? What else might complicate what you’ve said? Can we add nuance to this idea to make it more accurate? Qualifications involve words like: sometimes, may effect, often, in some cases, etc. These terms are not weak or to be avoided, they actually add accuracy and nuance.

A Link to a PDF Handout of this Writing Guide

Interpretive Essays

When you’re writing an interpretive essay, you definitely want to identify the author’s methods. What tone did the author use? What were the major characters? What was the main event? The plot of the story? Where was the setting? All of those things are important, but it’s not the only thing you want to do. This is only step 1. Step 2 is to evaluate and analyze the author’s methods. If you only identify them, you’re only going so far.

To have an effective interpretive essay, you want to evaluate the methods the author used instead of simply identifying them. One thing to keep in mind when you’re doing this is that there is a certain ambiguity in most literary works. This is the presence of multiple, somewhat inconsistent truths in a literary work. When you’re evaluating, you may say, “Oh, there was this good guy, but he made a bad decision. He did a bad thing.” You have to maybe come to a judgment on that person. Do you think that they were a good person or a bad person? Were they bad because of the bad thing they did, or was it forgivable because overall they were a good person?

Ambiguity in Literature

There is a lot of ambiguity and a lot of questions that come up in great literary works. That is because great literary works attempt to show life in all of its messy reality. It’s true; life is messy. Nothing is as cut and dry as it seems. You may see someone steal a loaf of bread and some peanut butter, but if they’re doing it because they’re bringing it home to their five small children because they’ve been laid off, then it’s harder to judge them for stealing the bread and peanut butter.

Keep in mind ambiguity whenever you’re coming up with your interpretation of literary works. A lot of literary works are going to pose more questions than answers. That’s good. They make you think. They don’t just tell you the answers; you’re left wondering, “I wonder what the author meant by that,” or “Was it really bad of this person to do that, or was it okay because of the situation? How do you feel about that?” Works that make you ask yourself questions like that tend to be the great literary works.

Whenever you are writing your interpretive essay, you want to respond to the likely questions of readers. If it’s a question you had, then it’s likely that other readers have the same question. They’ll be interested in your essay, because it’s going to answer or give a possible answer to one of the same questions that they had. One of the best ways to make your interpretive essay effective is to let other people read your early drafts. This may be hard, especially if you’re a shy or self-conscious writer, but you’re hopefully showing your writing to someone that you trust. That is, someone that’s going to give you not always positive but at least helpful criticism.

Addressing Reader Questions

One thing you should do is work their questions in. If they ask you, “Well, why did you say this?” or “I really thought the characters seemed this way. How did you get to this idea?” Work those questions in, because if your early readers are having those questions, your same readers reading the final draft are going to have those kinds of questions. Does your argument hold up? If you argued that someone was a good person, despite the bad thing they did, you have to make sure you put enough defense in there for your argument to hold up. Is the thesis statement effective? If you put in a thesis statement about honesty being the best policy always, then it’s going to be hard for you to write about how sometimes it’s alright to bend the rules.

You need to make sure that your interpretation is going to support your thesis statement. You may need to rewrite the thesis statement if you find that the rest of your paper doesn’t support your original one. This is one of the harder ones. Don’t get defensive if your readers are telling you things that you need to fix or change, or that they don’t like. You might be apt to get defensive, but, remember, they are people you trust. They’re your friends, and they’re telling you these things to help you, not to be mean. Another way to help yourself not be defensive and maybe edit your own paper is to try to view it as a reader.

Try to be detached and not view your paper as the author, but as someone reading something that they found in the newspaper, not necessarily something that you wrote. Then, it may be easier for you to be objective about what you need to change. The last, but very important, step here is to remember that early drafts are meant to be improved upon. It’s a draft for a reason. No one’s going to write a perfect paper the first time they write something down. There’s going to be something they can add to make it better. There is going to be some grammatical error they need to fix. Remember, it’s a draft. It’s meant to be drafted more times, edited, and added to until you get that final copy that you are really proud of.

When you’re writing an interpretive essay, first identify the author’s methods, but, most importantly, go back and evaluate those methods and come up with your own interpretation of the text. Because you’re interpreting it one way, you have to remember that there is ambiguity. Other people may interpret things other ways. Make sure that you are responding to some likely questions, but you’re leaving room for other answers whenever you’re coming up with your interpretation.

by Mometrix Test Preparation | This Page Last Updated: February 1, 2024

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement

- Giving Opportunities

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

Choosing the right evidence can be crucial to proving your argument, but your analysis of that evidence is equally important. Even when it seems like evidence may speak for itself, a reader needs to understand how the evidence connects to your argument. In addition, because analysis requires you to think critically and deeply about your evidence, it can improve your main argument by making it more specific and complex.

General Considerations

What Analysis Does: Breaks a work down to examine its various parts in close detail in order to see the work in a new light.

What an Analysis Essay Does: Chooses selective pieces of evidence and analysis in order to arrive at one single, complex argument that makes a claim about the deeper meaning behind the piece being analyzed. In the essay, each piece of evidence selected is paired with deep analysis that builds or elaborates on the last until the thesis idea is reached.

Analysis should be present in all essays. Wherever evidence is incorporated, analysis should be used to connect ideas back to your main argument.

In Practice

Answer Questions that Explain and Expand on the Evidence

Asking the kinds of questions that will lead to critical thought can access good analysis more easily. Such questions often anticipate what a reader might want to know as well. Questions can take the form of explaining the evidence or expanding on evidence; in other words, questions can give context or add meaning. Asking both kinds of questions is crucial to creating strong analysis.

When using evidence, ask yourself questions about context:

- What do I need to tell my audience about where this evidence came from?

- Is there a story behind this evidence?

- What is the historical situation in which this evidence was created?

Also ask yourself what the evidence implies about your argument:

- What aspects of this evidence would I like my audience to notice?

- Why did I choose this particular piece of evidence?

- Why does this evidence matter to my argument?

- Why is this evidence important in some ways, but not in others?

- How does this evidence contradict or confirm my argument? Does it do both?

- How does this evidence evolve or change my argument?

Example: “There’s nothing wrong with being a terrorist, as long as you win,” stated Paul Watson at an Animal Rights Convention.

Argument: Violent action is justified in order to protect animal rights.

Questions that explain the evidence: What did Watson mean by this statement? What else did he say in this speech that might give more context to this quote? What should the reader pay attention to here (for example, why is the word “terrorist” here especially important)?

Questions that expand on evidence: Why is this quote useful or not useful to the argument? How does Watson’s perspective help prove or disapprove the argument? How do you think the reader should interpret the word “terrorist”? Why should the reader take this quote seriously? How does this evidence evolve or complicate the argument—does what Watson said make the argument seem too biased or simple if activism can be related to terrorism?

Be Explicit

Because there may be multiple ways to interpret a piece of evidence, all evidence needs to be connected explicitly to your argument, even if the meaning of the evidence seems obvious to you. Plan on following any piece of evidence with, at the very least, one or two sentences of your honest interpretation of how the evidence connects to your argument—more if the evidence is significant.

Example: Paul Watson, a controversial animal rights activist, started his speech at the Animal Rights Convention with a provocative statement: “There’s nothing wrong with being a terrorist, as long as you win.” His use of the word ‘terrorist’ refers to aggressive actions taken by animal rights groups, including Sea Shepard, under the guise of protecting animals. While his quote might simply be intended to shock his audience, by comparing animal activism to terrorism, he mocks the fight against international terrorism.

Allow Analysis to Question the Argument

Sometimes frustrations with analysis can come from working with an argument that is too broad or too simple. The purpose of analysis is not only to show how evidence proves your argument, but also to discover the complexity of the argument. While answering questions that lead to analysis, if you come across something that contradicts the argument, allow your critical thinking to refine the argument.

Example: If one examined some more evidence about animal activism and it became clear that violence is sometimes the most effective measure, the argument could be modified. The more complex argument might be: “Violent action by animal activists might be akin to “terrorism” and deemed unacceptable, but it does make more of an immediate impact and gets more press. Without such aggressive actions, animal rights might be seen in a better light.”

Avoid Patterns of Weak or Empty Analysis

Sometimes sentences fill the space of analysis, but don’t actually answer questions about why and how the evidence connects to or evolves the argument. These moments of weak analysis negatively affect a writer’s credibility. The following are some patterns often found in passages of weak or empty analysis.

1. Offers a new fact or piece of evidence in place of analysis. Though it is possible to offer two pieces of evidence together and analyze them in relation to each other, simply offering another piece of evidence as a stand in for analysis weakens the argument. Telling the reader what happens next or another new fact is not analysis.

Example: “There’s nothing wrong with being a terrorist, as long as you win,” stated Paul Watson at an Animal Rights Convention. According to PETA, hunting is no longer needed for sustenance as it once was and it now constitutes violent aggression.

2. Uses an overly biased tone or restates claim rather than analyzing. Phrases such as “this is ridiculous” or “everyone can agree that this proves (fill in thesis here)” prevent the reader from seeing the subtle significance of the evidence you have chosen and often make a reader feel the writing is too biased.

Example: According to PETA, The Jane Goodall Institute estimates that 5,000 chimpanzees are killed by poachers annually. This ridiculous number proves that violence against animals justifies violent activist behavior.

3. Dismisses the relevance of the evidence. Bringing up a strong point and then shifting away from it rather than analyzing it can make evidence seem irrelevant. Statements such as “regardless of this evidence” or “nevertheless, we can still argue” before analyzing evidence can diminish the evidence all together.

Example: Paul Watson was expelled from the leadership of Greenpeace. Nevertheless, his vision of activism should be commended.

4. Strains logic or creates a generalization to arrive at the desired argument. Making evidence suit your needs rather than engaging in honest critical thinking can create fallacies in the argument and lower your credibility. It might also make the argument confusing.

Example: Some companies are taking part in the use of alternatives to animal testing. But some companies does not mean all and the ones who aren’t taking part are what gives animal activists the right to take drastic action.

5. Offers advice or a solution without first providing analysis. Telling a reader what should be done can be fine, but first explain how the evidence allows you to arrive at that conclusion.

Example: Greenpeace states that they attempt to save whales by putting themselves between the whaling ship and the whale, and they have been successful at gaining media support, but anyone who is a true activist needs to go further and put whalers at risk.

For the following pairings of evidence and analysis, identify what evasive moves are being made and come up with a precise question that would lead to better analysis. Imagine your working thesis is as follows: Message communications came to life in order to bring people closer together, to make it easier to stay connected and in some instances they have. More often however, these forms of communication seem to be pushing people apart because they are less personal.

1. An article in USA Today last year had the headline, “Can Love Blossom in a Text Message?” I’m sure most people’s gut reaction would be a resounding, “Of course not!” The article discusses a young woman whose boyfriend told her he loved her for the first time in a text message. Messaging is clearly pushing people apart.

2. In fact in the United States today, there are an estimated 250,146,921 wireless subscribers. Evidence shows that a person is more likely to first establish communication with someone you are interested in via text message or a form of online messaging via Facebook, Myspace, email, or instant messenger. People find these means of communication less stressful. This is because they are less personal.

3. This way of communicating is very new, with text message popularity skyrocketing within only the last five years, the invention of instant messaging gaining popular use through AOL beginning in 1998, and websites such as Myspace and Facebook invading our computers within only the last 5 years. Regardless of this change in communication technology, these forms of communication do not bring people together.

4. The way some people wish others “Happy Birthday” is another example. On birthdays, if you are on Facebook, your wall becomes flooded with happy birthday wishes, which is nice. However, if one of your close friends or perhaps a sibling simply wishes you a happy birthday on Facebook, you probably will feel a little cheated. It is important to know where you stand in your relationships, and if the person is actually important to you, you should take the time to call them in this kind of situation.

5. Studies suggest that over 90% of the meaning we derive from communication, we derive from the non-verbal cues. These nonverbal cues include body language, facial expression, eye movement and contact, posture, gestures, use of touch (such as hug or handshake), vocal intonation, rate of speech, and the information we gather from appearance (Applebaum, 108). It’s terrible to think that such important things are said with only a mere 10% of their meaning being properly conveyed. Phone calls can eliminate some of these problems.

6. Many people now have “Top Friends” on their Facebook profile where they rank their friends in order of importance. Sure most of us have a couple people who we refer to as our “best friends,” but never before this online ranking phenomenon has the order in which you rank your friends been public knowledge. This shows that friendship has lost all meaning.

1. argues with tone and uses a generalization 2. introduces new evidence and uses generalizations 3. dismisses evidence 4. offers advice or a solution and dismisses evidence 5. argues with tone and offers advice 6. uses a generalization

Resources: http://www.peta.org/mc/facts.asp http://www.greenpeace.org/international/about/history/paul-watson/

Last updated June 2011

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

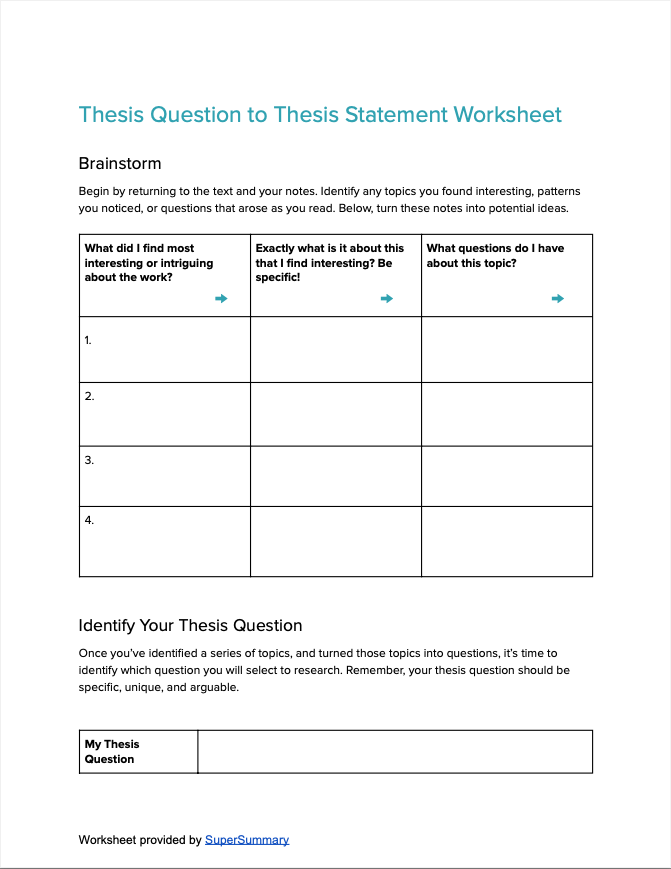

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

Step 6: Write an Outline

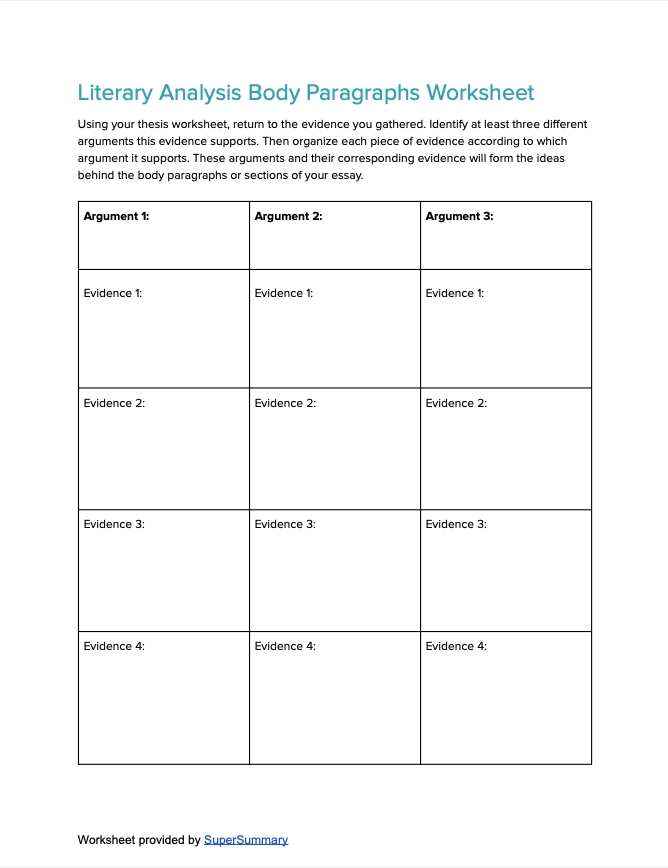

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.