- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Posted on 6th December 2017 by Saul Crandon

Introduction

Case-control and cohort studies are observational studies that lie near the middle of the hierarchy of evidence . These types of studies, along with randomised controlled trials, constitute analytical studies, whereas case reports and case series define descriptive studies (1). Although these studies are not ranked as highly as randomised controlled trials, they can provide strong evidence if designed appropriately.

Case-control studies

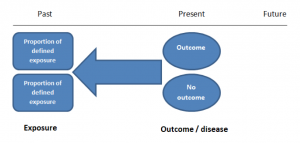

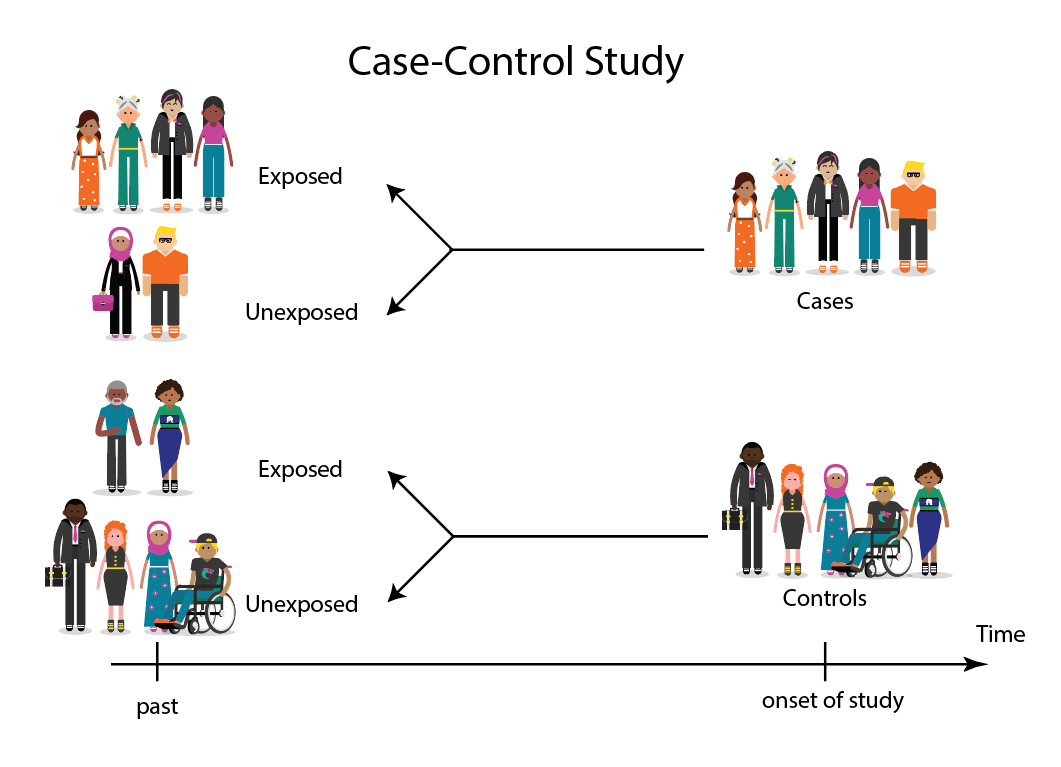

Case-control studies are retrospective. They clearly define two groups at the start: one with the outcome/disease and one without the outcome/disease. They look back to assess whether there is a statistically significant difference in the rates of exposure to a defined risk factor between the groups. See Figure 1 for a pictorial representation of a case-control study design. This can suggest associations between the risk factor and development of the disease in question, although no definitive causality can be drawn. The main outcome measure in case-control studies is odds ratio (OR) .

Figure 1. Case-control study design.

Cases should be selected based on objective inclusion and exclusion criteria from a reliable source such as a disease registry. An inherent issue with selecting cases is that a certain proportion of those with the disease would not have a formal diagnosis, may not present for medical care, may be misdiagnosed or may have died before getting a diagnosis. Regardless of how the cases are selected, they should be representative of the broader disease population that you are investigating to ensure generalisability.

Case-control studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their outcome / disease status.

As such, controls should also be selected carefully. It is possible to match controls to the cases selected on the basis of various factors (e.g. age, sex) to ensure these do not confound the study results. It may even increase statistical power and study precision by choosing up to three or four controls per case (2).

Case-controls can provide fast results and they are cheaper to perform than most other studies. The fact that the analysis is retrospective, allows rare diseases or diseases with long latency periods to be investigated. Furthermore, you can assess multiple exposures to get a better understanding of possible risk factors for the defined outcome / disease.

Nevertheless, as case-controls are retrospective, they are more prone to bias. One of the main examples is recall bias. Often case-control studies require the participants to self-report their exposure to a certain factor. Recall bias is the systematic difference in how the two groups may recall past events e.g. in a study investigating stillbirth, a mother who experienced this may recall the possible contributing factors a lot more vividly than a mother who had a healthy birth.

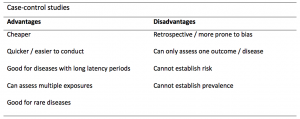

A summary of the pros and cons of case-control studies are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies.

Cohort studies

Cohort studies can be retrospective or prospective. Retrospective cohort studies are NOT the same as case-control studies.

In retrospective cohort studies, the exposure and outcomes have already happened. They are usually conducted on data that already exists (from prospective studies) and the exposures are defined before looking at the existing outcome data to see whether exposure to a risk factor is associated with a statistically significant difference in the outcome development rate.

Prospective cohort studies are more common. People are recruited into cohort studies regardless of their exposure or outcome status. This is one of their important strengths. People are often recruited because of their geographical area or occupation, for example, and researchers can then measure and analyse a range of exposures and outcomes.

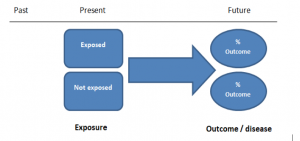

The study then follows these participants for a defined period to assess the proportion that develop the outcome/disease of interest. See Figure 2 for a pictorial representation of a cohort study design. Therefore, cohort studies are good for assessing prognosis, risk factors and harm. The outcome measure in cohort studies is usually a risk ratio / relative risk (RR).

Figure 2. Cohort study design.

Cohort studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their exposure status.

As a result, both exposed and unexposed groups should be recruited from the same source population. Another important consideration is attrition. If a significant number of participants are not followed up (lost, death, dropped out) then this may impact the validity of the study. Not only does it decrease the study’s power, but there may be attrition bias – a significant difference between the groups of those that did not complete the study.

Cohort studies can assess a range of outcomes allowing an exposure to be rigorously assessed for its impact in developing disease. Additionally, they are good for rare exposures, e.g. contact with a chemical radiation blast.

Whilst cohort studies are useful, they can be expensive and time-consuming, especially if a long follow-up period is chosen or the disease itself is rare or has a long latency.

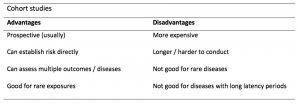

A summary of the pros and cons of cohort studies are provided in Table 2.

The Strengthening of Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE)

STROBE provides a checklist of important steps for conducting these types of studies, as well as acting as best-practice reporting guidelines (3). Both case-control and cohort studies are observational, with varying advantages and disadvantages. However, the most important factor to the quality of evidence these studies provide, is their methodological quality.

- Song, J. and Chung, K. Observational Studies: Cohort and Case-Control Studies . Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.  2010 Dec;126(6):2234-2242.

- Ury HK. Efficiency of case-control studies with multiple controls per case: Continuous or dichotomous data . Biometrics . 1975 Sep;31(3):643–649.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.  Lancet 2007 Oct;370(9596):1453-14577. PMID: 18064739.

Saul Crandon

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Very well presented, excellent clarifications. Has put me right back into class, literally!

Very clear and informative! Thank you.

very informative article.

Thank you for the easy to understand blog in cohort studies. I want to follow a group of people with and without a disease to see what health outcomes occurs to them in future such as hospitalisations, diagnoses, procedures etc, as I have many health outcomes to consider, my questions is how to make sure these outcomes has not occurred before the “exposure disease”. As, in cohort studies we are looking at incidence (new) cases, so if an outcome have occurred before the exposure, I can leave them out of the analysis. But because I am not looking at a single outcome which can be checked easily and if happened before exposure can be left out. I have EHR data, so all the exposure and outcome have occurred. my aim is to check the rates of different health outcomes between the exposed)dementia) and unexposed(non-dementia) individuals.

Very helpful information

Thanks for making this subject student friendly and easier to understand. A great help.

Thanks a lot. It really helped me to understand the topic. I am taking epidemiology class this winter, and your paper really saved me.

Happy new year.

Wow its amazing n simple way of briefing ,which i was enjoyed to learn this.its very easy n quick to pick ideas .. Thanks n stay connected

Saul you absolute melt! Really good work man

am a student of public health. This information is simple and well presented to the point. Thank you so much.

very helpful information provided here

really thanks for wonderful information because i doing my bachelor degree research by survival model

Quite informative thank you so much for the info please continue posting. An mph student with Africa university Zimbabwe.

Thank you this was so helpful amazing

Apreciated the information provided above.

So clear and perfect. The language is simple and superb.I am recommending this to all budding epidemiology students. Thanks a lot.

Great to hear, thank you AJ!

I have recently completed an investigational study where evidence of phlebitis was determined in a control cohort by data mining from electronic medical records. We then introduced an intervention in an attempt to reduce incidence of phlebitis in a second cohort. Again, results were determined by data mining. This was an expedited study, so there subjects were enrolled in a specific cohort based on date(s) of the drug infused. How do I define this study? Thanks so much.

thanks for the information and knowledge about observational studies. am a masters student in public health/epidemilogy of the faculty of medicines and pharmaceutical sciences , University of Dschang. this information is very explicit and straight to the point

Very much helpful

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Cluster Randomized Trials: Concepts

This blog summarizes the concepts of cluster randomization, and the logistical and statistical considerations while designing a cluster randomized controlled trial.

Expertise-based Randomized Controlled Trials

This blog summarizes the concepts of Expertise-based randomized controlled trials with a focus on the advantages and challenges associated with this type of study.

An introduction to different types of study design

Conducting successful research requires choosing the appropriate study design. This article describes the most common types of designs conducted by researchers.

A Practical Overview of Case-Control Studies in Clinical Practice

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH; Center for Surgery and Public Health, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH; Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH.

- 3 Department of Statistics, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO.

- PMID: 32658653

- DOI: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.009

Case-control studies are one of the major observational study designs for performing clinical research. The advantages of these study designs over other study designs are that they are relatively quick to perform, economical, and easy to design and implement. Case-control studies are particularly appropriate for studying disease outbreaks, rare diseases, or outcomes of interest. This article describes several types of case-control designs, with simple graphical displays to help understand their differences. Study design considerations are reviewed, including sample size, power, and measures associated with risk factors for clinical outcomes. Finally, we discuss the advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies and provide a checklist for authors and a framework of considerations to guide reviewers' comments.

Keywords: OR; case-cohort; case-crossover; matching; nested case-control; relative risk.

Copyright © 2020 American College of Chest Physicians. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Case-Control Studies*

- Guidelines as Topic

- Research Design / standards

- Research Design / statistics & numerical data*

Study Design 101: Case Control Study

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

A study that compares patients who have a disease or outcome of interest (cases) with patients who do not have the disease or outcome (controls), and looks back retrospectively to compare how frequently the exposure to a risk factor is present in each group to determine the relationship between the risk factor and the disease.

Case control studies are observational because no intervention is attempted and no attempt is made to alter the course of the disease. The goal is to retrospectively determine the exposure to the risk factor of interest from each of the two groups of individuals: cases and controls. These studies are designed to estimate odds.

Case control studies are also known as "retrospective studies" and "case-referent studies."

- Good for studying rare conditions or diseases

- Less time needed to conduct the study because the condition or disease has already occurred

- Lets you simultaneously look at multiple risk factors

- Useful as initial studies to establish an association

- Can answer questions that could not be answered through other study designs

Disadvantages

- Retrospective studies have more problems with data quality because they rely on memory and people with a condition will be more motivated to recall risk factors (also called recall bias).

- Not good for evaluating diagnostic tests because it's already clear that the cases have the condition and the controls do not

- It can be difficult to find a suitable control group

Design pitfalls to look out for

Care should be taken to avoid confounding, which arises when an exposure and an outcome are both strongly associated with a third variable. Controls should be subjects who might have been cases in the study but are selected independent of the exposure. Cases and controls should also not be "over-matched."

Is the control group appropriate for the population? Does the study use matching or pairing appropriately to avoid the effects of a confounding variable? Does it use appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria?

Fictitious Example

There is a suspicion that zinc oxide, the white non-absorbent sunscreen traditionally worn by lifeguards is more effective at preventing sunburns that lead to skin cancer than absorbent sunscreen lotions. A case-control study was conducted to investigate if exposure to zinc oxide is a more effective skin cancer prevention measure. The study involved comparing a group of former lifeguards that had developed cancer on their cheeks and noses (cases) to a group of lifeguards without this type of cancer (controls) and assess their prior exposure to zinc oxide or absorbent sunscreen lotions.

This study would be retrospective in that the former lifeguards would be asked to recall which type of sunscreen they used on their face and approximately how often. This could be either a matched or unmatched study, but efforts would need to be made to ensure that the former lifeguards are of the same average age, and lifeguarded for a similar number of seasons and amount of time per season.

Real-life Examples

Boubekri, M., Cheung, I., Reid, K., Wang, C., & Zee, P. (2014). Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: a case-control pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 10 (6), 603-611. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3780

This pilot study explored the impact of exposure to daylight on the health of office workers (measuring well-being and sleep quality subjectively, and light exposure, activity level and sleep-wake patterns via actigraphy). Individuals with windows in their workplaces had more light exposure, longer sleep duration, and more physical activity. They also reported a better scores in the areas of vitality and role limitations due to physical problems, better sleep quality and less sleep disturbances.

Togha, M., Razeghi Jahromi, S., Ghorbani, Z., Martami, F., & Seifishahpar, M. (2018). Serum Vitamin D Status in a Group of Migraine Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. Headache, 58 (10), 1530-1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13423

This case-control study compared serum vitamin D levels in individuals who experience migraine headaches with their matched controls. Studied over a period of thirty days, individuals with higher levels of serum Vitamin D was associated with lower odds of migraine headache.

Related Formulas

- Odds ratio in an unmatched study

- Odds ratio in a matched study

Related Terms

A patient with the disease or outcome of interest.

Confounding

When an exposure and an outcome are both strongly associated with a third variable.

A patient who does not have the disease or outcome.

Matched Design

Each case is matched individually with a control according to certain characteristics such as age and gender. It is important to remember that the concordant pairs (pairs in which the case and control are either both exposed or both not exposed) tell us nothing about the risk of exposure separately for cases or controls.

Observed Assignment

The method of assignment of individuals to study and control groups in observational studies when the investigator does not intervene to perform the assignment.

Unmatched Design

The controls are a sample from a suitable non-affected population.

Now test yourself!

1. Case Control Studies are prospective in that they follow the cases and controls over time and observe what occurs.

a) True b) False

2. Which of the following is an advantage of Case Control Studies?

a) They can simultaneously look at multiple risk factors. b) They are useful to initially establish an association between a risk factor and a disease or outcome. c) They take less time to complete because the condition or disease has already occurred. d) b and c only e) a, b, and c

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- Case Reports

- << Previous: Case Report

- Next: Cohort Study >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

Quantitative study designs: Case Control

Quantitative study designs.

- Introduction

- Cohort Studies

- Randomised Controlled Trial

Case Control

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Study Designs Home

In a Case-Control study there are two groups of people: one has a health issue (Case group), and this group is “matched” to a Control group without the health issue based on characteristics like age, gender, occupation. In this study type, we can look back in the patient’s histories to look for exposure to risk factors that are common to the Case group, but not the Control group. It was a case-control study that demonstrated a link between carcinoma of the lung and smoking tobacco . These studies estimate the odds between the exposure and the health outcome, however they cannot prove causality. Case-Control studies might also be referred to as retrospective or case-referent studies.

Stages of a Case-Control study

This diagram represents taking both the case (disease) and the control (no disease) groups and looking back at their histories to determine their exposure to possible contributing factors. The researchers then determine the likelihood of those factors contributing to the disease.

(FOR ACCESSIBILITY: A case control study is likely to show that most, but not all exposed people end up with the health issue, and some unexposed people may also develop the health issue)

Which Clinical Questions does Case-Control best answer?

Case-Control studies are best used for Prognosis questions.

For example: Do anticholinergic drugs increase the risk of dementia in later life? (See BMJ Case-Control study Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study )

What are the advantages and disadvantages to consider when using Case-Control?

* Confounding occurs when the elements of the study design invalidate the result. It is usually unintentional. It is important to avoid confounding, which can happen in a few ways within Case-Control studies. This explains why it is lower in the hierarchy of evidence, superior only to Case Studies.

What does a strong Case-Control study look like?

A strong study will have:

- Well-matched controls, similar background without being so similar that they are likely to end up with the same health issue (this can be easier said than done since the risk factors are unknown).

- Detailed medical histories are available, reducing the emphasis on a patient’s unreliable recall of their potential exposures.

What are the pitfalls to look for?

- Poorly matched or over-matched controls. Poorly matched means that not enough factors are similar between the Case and Control. E.g. age, gender, geography. Over-matched conversely means that so many things match (age, occupation, geography, health habits) that in all likelihood the Control group will also end up with the same health issue! Either of these situations could cause the study to become ineffective.

- Selection bias: Selection of Controls is biased. E.g. All Controls are in the hospital, so they’re likely already sick, they’re not a true sample of the wider population.

- Cases include persons showing early symptoms who never ended up having the illness.

Critical appraisal tools

To assist with critically appraising case control studies there are some tools / checklists you can use.

CASP - Case Control Checklist

JBI – Critical appraisal checklist for case control studies

CEBMA – Centre for Evidence Based Management – Critical appraisal questions (focus on leadership and management)

STROBE - Observational Studies checklists includes Case control

SIGN - Case-Control Studies Checklist

Real World Examples

Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report

- Doll, R., & Hill, A. B. (1950). Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. British Medical Journal , 2 (4682), 739–748. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2038856/

- Key Case-Control study linking tobacco smoking with lung cancer

- Notes a marked increase in incidence of Lung Cancer disproportionate to population growth.

- 20 London Hospitals contributed current Cases of lung, stomach, colon and rectum cancer via admissions, house-physician and radiotherapy diagnosis, non-cancer Controls were selected at each hospital of the same-sex and within 5 year age group of each.

- 1732 Cases and 743 Controls were interviewed for social class, gender, age, exposure to urban pollution, occupation and smoking habits.

- It was found that continued smoking from a younger age and smoking a greater number of cigarettes correlated with incidence of lung cancer.

Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study

- Richardson, K., Fox, C., Maidment, I., Steel, N., Loke, Y. K., Arthur, A., . . . Savva, G. M. (2018). Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study. BMJ , 361, k1315. Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1315.abstract .

- A recent study linking the duration and level of exposure to Anticholinergic drugs and subsequent onset of dementia.

- Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) was estimated in various drugs, the higher the exposure (measured as the ACB score) the greater likeliness of onset of dementia later in life.

- Antidepressant, urological, and antiparkinson drugs with an ACB score of 3 increased the risk of dementia. Gastrointestinal drugs with an ACB score of 3 were not strongly linked with onset of dementia.

- Tricyclic antidepressants such as Amitriptyline have an ACB score of 3 and are an example of a common area of concern.

Omega-3 deficiency associated with perinatal depression: Case-Control study

- Rees, A.-M., Austin, M.-P., Owen, C., & Parker, G. (2009). Omega-3 deficiency associated with perinatal depression: Case control study. Psychiatry Research , 166(2), 254-259. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178107004398 .

- During pregnancy women lose Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids to the developing foetus.

- There is a known link between Omgea-3 depletion and depression

- Sixteen depressed and 22 non-depressed women were recruited during their third trimester

- High levels of Omega-3 were associated with significantly lower levels of depression.

- Women with low levels of Omega-3 were six times more likely to be depressed during pregnancy.

References and Further Reading

Doll, R., & Hill, A. B. (1950). Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. British Medical Journal, 2(4682), 739–748. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2038856/

Greenhalgh, Trisha. How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=1642418 .

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. (2019). Study Design 101: Case-Control Study. Retrieved from https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu/tutorials/studydesign101/casecontrols.cfm

Hoffmann, T., Bennett, S., & Del Mar, C. (2017). Evidence-Based Practice Across the Health Professions (Third edition. ed.): Elsevier.

Lewallen, S., & Courtright, P. (1998). Epidemiology in practice: case-control studies. Community Eye Health, 11(28), 57. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1706071/

Pelham, B. W. a., & Blanton, H. (2013). Conducting research in psychology : measuring the weight of smoke /Brett W. Pelham, Hart Blanton (Fourth edition. ed.): Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Rees, A.-M., Austin, M.-P., Owen, C., & Parker, G. (2009). Omega-3 deficiency associated with perinatal depression: Case control study. Psychiatry Research, 166(2), 254-259. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178107004398

Richardson, K., Fox, C., Maidment, I., Steel, N., Loke, Y. K., Arthur, A., … Savva, G. M. (2018). Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study. BMJ, 361, k1315. Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1315.abstract

Statistics How To. (2019). Case-Control Study: Definition, Real Life Examples. Retrieved from https://www.statisticshowto.com/case-control-study/

- << Previous: Randomised Controlled Trial

- Next: Cross-Sectional Studies >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 11:37 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/quantitative-study-designs

Case Study Research Method in Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. Typically, data is gathered from various sources using several methods (e.g., observations & interviews).

The case study research method originated in clinical medicine (the case history, i.e., the patient’s personal history). In psychology, case studies are often confined to the study of a particular individual.

The information is mainly biographical and relates to events in the individual’s past (i.e., retrospective), as well as to significant events that are currently occurring in his or her everyday life.

The case study is not a research method, but researchers select methods of data collection and analysis that will generate material suitable for case studies.

Freud (1909a, 1909b) conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

This makes it clear that the case study is a method that should only be used by a psychologist, therapist, or psychiatrist, i.e., someone with a professional qualification.

There is an ethical issue of competence. Only someone qualified to diagnose and treat a person can conduct a formal case study relating to atypical (i.e., abnormal) behavior or atypical development.

Famous Case Studies

- Anna O – One of the most famous case studies, documenting psychoanalyst Josef Breuer’s treatment of “Anna O” (real name Bertha Pappenheim) for hysteria in the late 1800s using early psychoanalytic theory.

- Little Hans – A child psychoanalysis case study published by Sigmund Freud in 1909 analyzing his five-year-old patient Herbert Graf’s house phobia as related to the Oedipus complex.

- Bruce/Brenda – Gender identity case of the boy (Bruce) whose botched circumcision led psychologist John Money to advise gender reassignment and raise him as a girl (Brenda) in the 1960s.

- Genie Wiley – Linguistics/psychological development case of the victim of extreme isolation abuse who was studied in 1970s California for effects of early language deprivation on acquiring speech later in life.

- Phineas Gage – One of the most famous neuropsychology case studies analyzes personality changes in railroad worker Phineas Gage after an 1848 brain injury involving a tamping iron piercing his skull.

Clinical Case Studies

- Studying the effectiveness of psychotherapy approaches with an individual patient

- Assessing and treating mental illnesses like depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD

- Neuropsychological cases investigating brain injuries or disorders

Child Psychology Case Studies

- Studying psychological development from birth through adolescence

- Cases of learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, ADHD

- Effects of trauma, abuse, deprivation on development

Types of Case Studies

- Explanatory case studies : Used to explore causation in order to find underlying principles. Helpful for doing qualitative analysis to explain presumed causal links.

- Exploratory case studies : Used to explore situations where an intervention being evaluated has no clear set of outcomes. It helps define questions and hypotheses for future research.

- Descriptive case studies : Describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred. It is helpful for illustrating certain topics within an evaluation.

- Multiple-case studies : Used to explore differences between cases and replicate findings across cases. Helpful for comparing and contrasting specific cases.

- Intrinsic : Used to gain a better understanding of a particular case. Helpful for capturing the complexity of a single case.

- Collective : Used to explore a general phenomenon using multiple case studies. Helpful for jointly studying a group of cases in order to inquire into the phenomenon.

Where Do You Find Data for a Case Study?

There are several places to find data for a case study. The key is to gather data from multiple sources to get a complete picture of the case and corroborate facts or findings through triangulation of evidence. Most of this information is likely qualitative (i.e., verbal description rather than measurement), but the psychologist might also collect numerical data.

1. Primary sources

- Interviews – Interviewing key people related to the case to get their perspectives and insights. The interview is an extremely effective procedure for obtaining information about an individual, and it may be used to collect comments from the person’s friends, parents, employer, workmates, and others who have a good knowledge of the person, as well as to obtain facts from the person him or herself.

- Observations – Observing behaviors, interactions, processes, etc., related to the case as they unfold in real-time.

- Documents & Records – Reviewing private documents, diaries, public records, correspondence, meeting minutes, etc., relevant to the case.

2. Secondary sources

- News/Media – News coverage of events related to the case study.

- Academic articles – Journal articles, dissertations etc. that discuss the case.

- Government reports – Official data and records related to the case context.

- Books/films – Books, documentaries or films discussing the case.

3. Archival records

Searching historical archives, museum collections and databases to find relevant documents, visual/audio records related to the case history and context.

Public archives like newspapers, organizational records, photographic collections could all include potentially relevant pieces of information to shed light on attitudes, cultural perspectives, common practices and historical contexts related to psychology.

4. Organizational records

Organizational records offer the advantage of often having large datasets collected over time that can reveal or confirm psychological insights.

Of course, privacy and ethical concerns regarding confidential data must be navigated carefully.

However, with proper protocols, organizational records can provide invaluable context and empirical depth to qualitative case studies exploring the intersection of psychology and organizations.

- Organizational/industrial psychology research : Organizational records like employee surveys, turnover/retention data, policies, incident reports etc. may provide insight into topics like job satisfaction, workplace culture and dynamics, leadership issues, employee behaviors etc.

- Clinical psychology : Therapists/hospitals may grant access to anonymized medical records to study aspects like assessments, diagnoses, treatment plans etc. This could shed light on clinical practices.

- School psychology : Studies could utilize anonymized student records like test scores, grades, disciplinary issues, and counseling referrals to study child development, learning barriers, effectiveness of support programs, and more.

How do I Write a Case Study in Psychology?

Follow specified case study guidelines provided by a journal or your psychology tutor. General components of clinical case studies include: background, symptoms, assessments, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Interpreting the information means the researcher decides what to include or leave out. A good case study should always clarify which information is the factual description and which is an inference or the researcher’s opinion.

1. Introduction

- Provide background on the case context and why it is of interest, presenting background information like demographics, relevant history, and presenting problem.

- Compare briefly to similar published cases if applicable. Clearly state the focus/importance of the case.

2. Case Presentation

- Describe the presenting problem in detail, including symptoms, duration,and impact on daily life.

- Include client demographics like age and gender, information about social relationships, and mental health history.

- Describe all physical, emotional, and/or sensory symptoms reported by the client.

- Use patient quotes to describe the initial complaint verbatim. Follow with full-sentence summaries of relevant history details gathered, including key components that led to a working diagnosis.

- Summarize clinical exam results, namely orthopedic/neurological tests, imaging, lab tests, etc. Note actual results rather than subjective conclusions. Provide images if clearly reproducible/anonymized.

- Clearly state the working diagnosis or clinical impression before transitioning to management.

3. Management and Outcome

- Indicate the total duration of care and number of treatments given over what timeframe. Use specific names/descriptions for any therapies/interventions applied.

- Present the results of the intervention,including any quantitative or qualitative data collected.

- For outcomes, utilize visual analog scales for pain, medication usage logs, etc., if possible. Include patient self-reports of improvement/worsening of symptoms. Note the reason for discharge/end of care.

4. Discussion

- Analyze the case, exploring contributing factors, limitations of the study, and connections to existing research.

- Analyze the effectiveness of the intervention,considering factors like participant adherence, limitations of the study, and potential alternative explanations for the results.

- Identify any questions raised in the case analysis and relate insights to established theories and current research if applicable. Avoid definitive claims about physiological explanations.

- Offer clinical implications, and suggest future research directions.

5. Additional Items

- Thank specific assistants for writing support only. No patient acknowledgments.

- References should directly support any key claims or quotes included.

- Use tables/figures/images only if substantially informative. Include permissions and legends/explanatory notes.

- Provides detailed (rich qualitative) information.

- Provides insight for further research.

- Permitting investigation of otherwise impractical (or unethical) situations.

Case studies allow a researcher to investigate a topic in far more detail than might be possible if they were trying to deal with a large number of research participants (nomothetic approach) with the aim of ‘averaging’.

Because of their in-depth, multi-sided approach, case studies often shed light on aspects of human thinking and behavior that would be unethical or impractical to study in other ways.

Research that only looks into the measurable aspects of human behavior is not likely to give us insights into the subjective dimension of experience, which is important to psychoanalytic and humanistic psychologists.

Case studies are often used in exploratory research. They can help us generate new ideas (that might be tested by other methods). They are an important way of illustrating theories and can help show how different aspects of a person’s life are related to each other.

The method is, therefore, important for psychologists who adopt a holistic point of view (i.e., humanistic psychologists ).

Limitations

- Lacking scientific rigor and providing little basis for generalization of results to the wider population.

- Researchers’ own subjective feelings may influence the case study (researcher bias).

- Difficult to replicate.

- Time-consuming and expensive.

- The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources.

Because a case study deals with only one person/event/group, we can never be sure if the case study investigated is representative of the wider body of “similar” instances. This means the conclusions drawn from a particular case may not be transferable to other settings.

Because case studies are based on the analysis of qualitative (i.e., descriptive) data , a lot depends on the psychologist’s interpretation of the information she has acquired.

This means that there is a lot of scope for Anna O , and it could be that the subjective opinions of the psychologist intrude in the assessment of what the data means.

For example, Freud has been criticized for producing case studies in which the information was sometimes distorted to fit particular behavioral theories (e.g., Little Hans ).

This is also true of Money’s interpretation of the Bruce/Brenda case study (Diamond, 1997) when he ignored evidence that went against his theory.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on hysteria . Standard Edition 2: London.

Curtiss, S. (1981). Genie: The case of a modern wild child .

Diamond, M., & Sigmundson, K. (1997). Sex Reassignment at Birth: Long-term Review and Clinical Implications. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine , 151(3), 298-304

Freud, S. (1909a). Analysis of a phobia of a five year old boy. In The Pelican Freud Library (1977), Vol 8, Case Histories 1, pages 169-306

Freud, S. (1909b). Bemerkungen über einen Fall von Zwangsneurose (Der “Rattenmann”). Jb. psychoanal. psychopathol. Forsch ., I, p. 357-421; GW, VII, p. 379-463; Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis, SE , 10: 151-318.

Harlow J. M. (1848). Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 39 , 389–393.

Harlow, J. M. (1868). Recovery from the Passage of an Iron Bar through the Head . Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society. 2 (3), 327-347.

Money, J., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & Woman, Boy & Girl : The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Money, J., & Tucker, P. (1975). Sexual signatures: On being a man or a woman.

Further Information

- Case Study Approach

- Case Study Method

- Enhancing the Quality of Case Studies in Health Services Research

- “We do things together” A case study of “couplehood” in dementia

- Using mixed methods for evaluating an integrative approach to cancer care: a case study

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Case-Control Studies : Using “Real-world” Evidence to Assess Association

- 1 Office of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland

- JAMA Guide to Statistics and Methods Mediation Analysis Hopin Lee, PhD; Robert D. Herbert, PhD; James H. McAuley, PhD JAMA

- Comment & Response Case-Control Studies Tony Blakely, PhD; Neil Pearce, PhD; John Lynch, PhD JAMA

- Comment & Response Case-Control Studies—Reply Telba Z. Irony, PhD JAMA

- Original Investigation Cardiovascular Risk and Inhaled Long-Acting Bronchodilators Meng-Ting Wang, PhD; Jun-Ting Liou, MD; Chen Wei Lin, BS; Chen-Liang Tsai, MD; Yun-Han Wang, MS, BPharm; Yu-Juei Hsu, MD, PhD; Jyun-Heng Lai, MS, BPharm JAMA Internal Medicine

Associations between patient characteristics or treatments received and clinical outcomes are often first described using observational data, such as data arising through usual clinical care without the experimental assignment of treatments that occurs in a randomized clinical trial (RCT). These data based on usual clinical care are referred to by some as “real-world” data. A key strategy for efficiently finding such associations is to use a case-control study. 1 In a recent issue of JAMA Internal Medicine , Wang et al 2 assessed the association between cardiovascular disease (CVD) and use of inhaled long-acting β 2 -agonists (LABAs) or long-acting antimuscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), utilizing a nested case-control study.

Read More About

Irony TZ. Case-Control Studies : Using “Real-world” Evidence to Assess Association . JAMA. 2018;320(10):1027–1028. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.12115

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Chapter 8. Case-control and cross sectional studies

Case-control studies

Selection of cases, selection of controls, ascertainment of exposure, cross sectional studies.

- Chapter 1. What is epidemiology?

- Chapter 2. Quantifying disease in populations

- Chapter 3. Comparing disease rates

- Chapter 4. Measurement error and bias

- Chapter 5. Planning and conducting a survey

- Chapter 6. Ecological studies

- Chapter 7. Longitudinal studies

- Chapter 9. Experimental studies

- Chapter 10. Screening

- Chapter 11. Outbreaks of disease

- Chapter 12. Reading epidemiological reports

- Chapter 13. Further reading

Follow us on

Content links.

- Collections

- Health in South Asia

- Women’s, children’s & adolescents’ health

- News and views

- BMJ Opinion

- Rapid responses

- Editorial staff

- BMJ in the USA

- BMJ in South Asia

- Submit your paper

- BMA members

- Subscribers

- Advertisers and sponsors

Explore BMJ

- Our company

- BMJ Careers

- BMJ Learning

- BMJ Masterclasses

- BMJ Journals

- BMJ Student

- Academic edition of The BMJ

- BMJ Best Practice

- The BMJ Awards

- Email alerts

- Activate subscription

Information

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The effects of person-centred active rehabilitation on symptoms of suspected Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: A mixed-methods single case design

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Health Professions, Faculty of Health and Education, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Faculty of Health and Education, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Rachael Hearn,

- James Selfe,

- Maria I. Cordero,

- Nick Dobbin

- Published: May 30, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260

- Reader Comments

The objective was to investigate the effectiveness of a person-centred active rehabilitation programme on symptoms associated with suspected Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). This was accomplished by (1) assessing the effect that a person-centred active rehabilitation programme had on participant symptoms, and (2) exploring how temporal contextual factors affected the participants’ experience with, and perceived effectiveness of, the active rehabilitation programme.

A twelve-month mixed-methods single case experimental research design was used with six cases (participants). Individual cases were involved in a 51-week study period including an initial interview and three-week baseline phase. Cases were then randomly allocated to one of two n-of-1 study designs (i.e., A-B, B-A, B-A, A-B or B-A, A-B, A-B, B-A) where A and B represent a non-intervention and intervention phase, respectively. Interviews were conducted regularly throughout the study whilst outcome measures were assessed at each follow-up. Analysis of the data included visual, statistical, and qualitative analysis.

Visual and statistical analysis of cognitive and executive function, and mindful attention, demonstrated trivial-to-large effects with the summary reflecting positive or unclear results. A mixed picture was observed for mood and behaviour with effects considered trivial-to-large, and the summary demonstrating positive, unclear and negative effects. Qualitative analysis indicated a perceived improvement in outcome measures such as memory, attention, anxiety, and emotional control despite mixed quantitative findings whilst a clear impact of contextual factors, such as COVID-19, the political atmosphere, exercise tolerance, programme progression, and motivation were evident during the intervention.

Conclusions

This study has provided primary-level evidence to suggest active rehabilitation as a potential intervention for the management of suspected CTE symptoms. This study has also demonstrated the benefit of a person-centred approach to both clinical research and practice, particularly by considering contextual factors for a better understanding of an intervention effect.

Citation: Hearn R, Selfe J, Cordero MI, Dobbin N (2024) The effects of person-centred active rehabilitation on symptoms of suspected Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: A mixed-methods single case design. PLoS ONE 19(5): e0302260. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260

Editor: Simone Varrasi, University of Catania, ITALY

Received: December 21, 2023; Accepted: March 31, 2024; Published: May 30, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Hearn et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in this study are available from Manchester Metropolitan University e-space: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/view/datasets/ .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) was formally defined by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke/National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NINDS/NIBIB) consensus panel in 2015. CTE is a neurodegenerative pathology defined by its unique, irregular pattern of tau protein accumulation around small blood vessels at the base of the cortical sulci [ 1 ]. While CTE has been known by many since at least 1928, the clinical profile has consistently been linked to an exposure to repetitive brain injury. CTE has now been diagnosed post-mortem in former American football, football (soccer), rugby, Australian rules football, ice hockey, baseball, and wrestling athletes, as well as military personnel and domestic abuse victims [ 1 – 3 ]. The inability to diagnose CTE pre-death has led to the development of a clinical profile termed Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome (TES). This clinical profile has enabled researchers to identify individuals with symptoms associated with suspected CTE allowing for early management and development of active rehabilitation or treatment options [ 2 , 4 – 6 ].

Currently, no evidence-based therapy has been developed to treat or manage symptoms associated with CTE to our knowledge. Cantu and Budson [ 4 ] provided the first expert review outlining potential lifestyle modifications and symptom management strategies for CTE. Recommendations included exercise, active rehabilitation, diet, cognitive rehabilitation, mood/behavioural therapy, occupational therapy, vestibular and motor therapy, and pharmacological therapy. This expert opinion has been reiterated by Fusco et al. [ 7 ] and Rossi et al. [ 8 ] in expert opinions or narrative reviews. Themes including cognitive and motor rehabilitation therapy, mindfulness, mood/behavioural therapy, occupational therapy, diet, exercise, and active rehabilitation were suggested to help manage neuropsychiatric symptoms of CTE [ 7 , 8 ]. Finally, an umbrella review [ 9 ] has reported the effect that active rehabilitation has on other tauopathies with symptoms associated with CTE. This review found that various forms of active rehabilitation had a positive effect (standardised mean difference ranging from 0.11 to 0.88) on symptoms of cognitive and motor function in populations diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

Despite being an area of growing interest amongst researchers and clinicians, current evidence is largely limited to secondary level research. Whilst various forms of management strategies have been suggested (e.g., active rehabilitation), few have examined the efficacy of this. It is also important to consider the patient within a rehabilitation or management approach. A person-centred care approach allows for the management of patients with a unique set of symptoms which is likely to be particularly important when managing individuals with suspected CTE. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of person-centred active rehabilitation on symptoms of TES, providing the first primary level research exploring a potential management for CTE symptoms. This was accomplished by: (1) assessing the effect that a person-centred active rehabilitation programme had on participant symptoms suspected to be associated with the development of CTE, and (2) exploring how proximal (individual—interpersonal and intrapersonal) and distal (environmental—socio-economic, rural-urban differences and immigration background) factors affected the participants’ experience with, and perceived effectiveness of, the active rehabilitation programme through repeated interviews during the course of the intervention.

Materials and methods

A mixed-methods single case research (MMSCR) design was used for this study with an n-of-1 framework. The study was designed and reported in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for N-of-1 trials [ 10 , 11 ]. Ethical approval was granted by the Faculty of Health, Psychology and Social Care Research Ethics and Governance Committee at Manchester Metropolitan University (ID: 11822).

Eligibility criteria

Individuals between the age 20 and 60 years who met the 2014 TES criteria [ 6 ], spoke/read English, and were at least one year retired from competitive sport were eligible for inclusion. The 2014 TES criteria was used as the updated criteria by Katz and colleagues [ 5 ] was not available at the start of the study. An age range of 20 to 60 years allowed for sufficient exposure to mTBI/contact sport while minimising the chance of concomitant neurodegenerative disease, presence of dementia, and other neurological disorders. Individuals diagnosed with dementia were excluded.

At any time during data collection, withdrawal could be explicitly expressed by the participant. Withdrawal was assumed if the participant (1) missed more than two follow-up interviews in a row, or (2) did not respond to at least two contact attempts made by the researcher seeking to schedule a follow-up interview. Withdrawal was also discussed if the participant expressed dissent with the study procedures. In the event of participant withdrawal, any data where a full data collection cycle had been completed (A-B matched pair) was included in the analysis.

Materials and procedures

General procedure..

Individual cases (participants) were involved for 51 weeks, with recruitment and study commencement occurring on a rolling basis starting in April 2020 and ending in June 2021. The study began with an initial interview, followed by a three-week baseline phase. Participants were then randomly allocated to one of two systematic counterbalanced n-of-1 study designs, the first being A-B, B-A, B-A, A-B and the second being B-A, A-B, A-B, B-A, where ‘A’ indicates a non-intervention phase and ‘B’ indicates an intervention phase. Each paired phase (A-B or B-A) lasted twelve weeks and consisted of six interviews which took place every two weeks. A schematic overview of the study is illustrated in Fig 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Note: A = non-intervention phase. B–intervention phase.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.g001

Initial interview and screening assessments.

An initial interview was conducted to (1), screen the participant for study eligibility, ensuring they met clinical criteria for the presence of TES, and (2), to screen the participant for evidence of potential cognitive impairment, changes in mood/behaviour, or motor impairment associated with CTE which could be assessed during the three-week baseline period. To date, there is no established battery of assessments relevant to the population used in this study; thus, a pragmatic approach was adopted. The initial interview began with three core screening assessments to measure levels of cognitive function, mood/behavioural symptoms, and motor function ( S1 Table ). The initial meeting concluded with a semi-structured interview that sought to elicit further information related to the eligibility criteria and provided the participant with an opportunity to share information on relevant sporting history, medical history, family medical history, and any other further symptoms or concerns. In line with a person-centred care approach, participants also gave information regarding activity capabilities and preferences to inform the design of the active rehabilitation programme.

Baseline phase and follow-ups.

The three-week baseline period sought to establish the presence of measurable impairment. The assessments used were individualised for each case based on relevance and symptoms reported in the initial interview. Any symptom of TES had the potential for inclusion. A description of all assessments used in the study can be found in S2 Table . To reduce the burden on participants, a five-assessment limit was implemented. For those who did not reach the five-assessment limit, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was included to provide further support to the contextual information gathered during the follow-up interviews.

During each follow-up, participants completed an online survey consisting of self-report symptom assessments. The online survey also gave open box to submit a daily activity log. This log allowed participants to report daily log of their physical activity as well as additional contextual information related to their symptoms and programme experience. Participants also took part in a semi-structured follow-up interview at each data collection point. The semi-structured interviews primarily sought to create a person-centred care environment, promoting factors such as understanding the participant as a person and encouraging involvement in the co-design of the active rehabilitation. The aim of these interviews was to understand i) how the presence of the person-centred active rehabilitation programme affected the symptoms of interest, ii) how the participant described their experience with the rehabilitation programme and prescription, iii) how proximal and distal factors may have influenced the participants symptom levels, and iv) how proximal and distal factors may have influenced their experience with or effect of the programme.

Intervention delivery.

The setting of the study was entirely online. Any outcome assessments used were recorded via Qualtrics XM (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah, USA). The intervention programme was distributed via email and accompanied with online tutorial videos.

During an intervention phase (B phase), participants completed one resistance training session and one cardiovascular session each week. During a non-intervention phase (A phase) the prescribed exercises were removed, but participants were allowed to continue with habitual activities. Care was taken to ensure programme prescriptions resulted in a greater training load during intervention phases relative to the non-intervention phases.

The training programme was tailored by mode, duration, and intensity based on participant needs, preferences, facilities, and strength/fitness levels as understood from the semi-structured interview. Intensity for the resistance training programmes was prescribed using a modified rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale [ 12 ]. The intensity of the cardiovascular training programme was prescribed using the Borg 6–20 scale given its linear relationship with heart rate [ 12 ].

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis..

Visual analysis of the quantitative data followed a modified framework presented by Wolfe and colleagues [ 13 ], created in accordance with The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) Single-Case Design Standards [ 14 ]. Initially, a trend in the data was established for each of the paired non-intervention and intervention phases using a split middle trend (SMT) line [ 15 ]. The SMT line was then used to predict outcome measures for the subsequent phase. The size of the effect was estimated using a modified point system [ 13 ] based on the following:

- Evidence of change in level, trend and/or variability = 1.0 point

- Change was immediate, there was less than 30% of data overlap, or there was evidence of consistency between phase-types (intervention/non-intervention) = 0.25 point

After summing the scores, 0–2 indicates unclear behavioural change; 3–4 a small behavioural change; 5–6 a moderate behavioural change; 7–8 a large behavioural change.

To support the visual analysis and future research (e.g., sample size, meta-analyses), within-case standardized mean difference (WC-SMD) and non-overlap of all pairs (NAP) with 95% confidence limits were calculated [ 16 ]. SMDs were classified as: <2.0 trivial; 0.20–0.50, small; 0.51–0.80, moderate; >0.80, large [ 17 ]. NAP was interpreted as a probability that a randomly selected datapoint in the intervention (B) phase was above or below (depending on if an increase or decrease is desirable) a randomly selected datapoint in the non-intervention (A) phase [ 16 ].

Qualitative analysis.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim . Transcriptions were then read to identify content related to the topics of interest based on deductive analysis a-priori . Additional points of interest that also emerged were included via inductive analysis. To maintain trustworthiness through confirmability, all authors were given a random selection of transcripts to analyse. Qualitative analysis followed the explanation building approach outlined by Yin [ 18 ]. The following propositions were initially determined:

- The presence of the person-centred active rehabilitation programme had a positive effect on the participant’s symptoms of interest.

- The needs and preferences of the participant regarding the rehabilitation mode and prescription were met.

- Proximal and distal factors influenced i) the participant’s reported symptom levels, ii) the participant’s experience with the active rehabilitation programme, and iii) the effect of the active rehabilitation programme.

While a total of twenty-four follow-up interviews were available, a pragmatic approach for qualitative analysis was adopted. The sample of interviews used in this study consisted of those that took place at the end of each A-B paired phase (e.g., A1.3, B2.3, B3.3, and A4.3) to provide a more global view of the participant perspective as it related to the phase (whether A or B) and proximal and distal factors. A summary of results is presented in a narrative and visual format.

Participant characteristics

Ten participants were recruited for the study. Two participants did not demonstrate a measurable impairment during the screening or baseline phase in one of the three core clinical features and therefore did not meet eligibility criteria. A further two participants withdrew from the study before they completed an entire A-B phase. In both instances, the participant did not respond to at least two contact attempts made by the primary author to schedule follow-up interviews. A reason for withdrawal was not stated by either participant. In line with the study protocol, their data was withdrawn from the study. A total of six participants completed all aspects and were included in the final analysis.

Participant characteristics, informed by the initial semi-structured interview and baseline phase, can be found in Table 1 . Results are presented using pseudonyms to maintain anonymity.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.t001

Fig 2 illustrates a complete study timeline across all participants along with the sequence of intervention (B) and non-intervention (A) phases. This figure also provides key information on the COVID pandemic and the restrictions in place for each participant at the time of data collection.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.g002

Fig 3 presents results from the PSS assessment.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.g003

Participant activity levels

Participant were habitually active during the intervention engaging in various forms of physical activity including leisure, exercise, and sport. Table 2 presents a summary of the activities reported by participants during both intervention (B) and non-intervention (A) phases with bolded text being the prescribed activities.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.t002

Quantitative analysis

Table 3 provides a summary of the six individual cases, including visual and statistical analysis, across each symptom of interest. Individual case results can be found in S3 – S8 Tables. The effect that active rehabilitation had on symptoms of motor function was not reported as no participants included in the study had any measurable motor impairments.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.t003

Figs 4 and 5 provide visual results of outcome measures related to cognitive function. Effects on general cognitive function ( Fig 4 ) varied, with one participant (Niall) demonstrating a positive effect, one participant (Kristen) demonstrating a negative effect, and one participant (Simon) demonstrating an unclear effect. It should be noted that levels of general cognitive function consistently demonstrated an upward trend across intervention phases throughout the study for Simon, indicating a potential positive effect; however, statistical analysis supports an unclear effect. Visual and statistical analysis observed consistent overlap in all three cases as well. Levels of cognitive function were higher in the final phase for all three cases compared to those levels reported in the first study phase. Effects on mindful attention ( Fig 4 ) also varied, with one case demonstrating negative visual and statistical analysis (Simon) and one demonstrating a small visual but trivial statistical effect (Abel). High levels of variability throughout the study should be noted here along with consistent overlap between phases; therefore, it is difficult to determine the effect active rehabilitation had on levels of mindful attention.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.g004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.g005

Though the WC-SMD ranged from trivial to large, four of the six participants demonstrated a positive effect (Niall, Luigi, Abel, Simon) for measures of executive function ( Fig 5 ). Three of these participants (Niall, Luigi, Simon) also reported higher levels of executive function at the final phase of the study compared to the start of the study. Only Abel reported worse scores during the final phase of the study; however, a large WC-SMD (1.69) and NAP value of 0.79 suggests a positive effect of active rehabilitation overall. It should be noted that Kristen consistently demonstrated decreased variability of scores in non-intervention phases indicating more stable results for executive function in the absence of an active rehabilitation programme. This would suggest that the presence of an active rehabilitation programme had the potential to influence levels of outcome measures, albeit with a lack of statistical certainty. All cases demonstrated consistent overlap with visual analysis; however, NAP values in three cases (Niall, Abel, Simon) demonstrated a higher probability of increased executive function in intervention phases.

Figs 6 and 7 provide visual results of outcome measures related to mood and behaviour. The effect of active rehabilitation on outcome measures considered ‘core clinical features’ according to TES clinical criteria (depression, irritability, social isolation/loneliness) ( Fig 6 ) varied. One participant (Luigi) demonstrated a large positive effect on levels of depression, supported by both visual and statistical analysis; however, three participants (Kristen, Abel, Simon) demonstrated a small, negative effect on levels of depression. Interestingly, all participants aside from one (Simon) reported lower levels of depression during the final phase of the study compared to initial levels. There was no consistency of patterns in variability or trend, but overlap between phases was consistently present. NAP values also varied, indicating a variation in the likelihood of a randomly selected point taken during an intervention phase resulting in lower depression scores. Only one participant reported symptoms of loneliness and social isolation (Niall), and one participant reported symptoms of irritability (Luigi). In both instances, visual analysis indicated a positive effect. Levels of loneliness demonstrated a consistent downward trend during intervention phases despite increased variability. It should also be noted that Luigi demonstrated decreased variability for levels of irritability across intervention phases. A positive effect is further supported by improved levels reported during the final phase of the study compared to initial levels, as well as a general decline observed across the entire study; however, statistical analysis reports a trivial effect in both outcome measures.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.g006

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.g007

The effect of active rehabilitation on outcome measures considered ‘supportive clinical features’ according to TES clinical criteria (anxiety, sleep quality/insomnia) ( Fig 7 ) also varied. One participant (Luigi) reported a small-to-moderate effect on levels of anxiety, supported by visual and statistical analysis; however, Kristen and Abel reported a moderate, negative effect. The effect of active rehabilitation on Gemma’s level of anxiety was unclear. Visual analysis demonstrated a small effect; however, statistical analysis reports the effect as trivial. Interestingly, all participants demonstrated reduced levels of anxiety during the final phase of the study compared to those levels reported during the initial phase; however, overlap was present between all phases across all cases suggesting a temporal pattern of change. Only Kristen reported NAP levels which could suggest a greater probability of lower levels of anxiety in non-intervention phases (NAP = 0.25). It should be noted that Gemma consistently demonstrated a downward trend in levels of anxiety in intervention phases. Only one participant reported symptoms of reduced sleep quality and insomnia (Kristen). Despite WC-SMD reporting a small negative effect, visual analysis reported a trivial effect. Further, NAP suggests the probability randomly selected data point for sleep score being lower during an intervention phase was 43%. It should be noted that Kristen’s sleep score was lower at the end of the study compared to those reported at the start of the study, indicating an improvement in symptoms.

Qualitative data

Fig 8 presents a visual summary of the topics emerged from the semi-structured interviews, including information relevant to the context of the study (8A), intervention experience (8B), and perception towards the effect of the intervention on symptoms (8C). Topics of discussion highlighted in green present information that may have contributed to a positive participant experience and generally included improved memory, coping skills emotional control and anxiety, the role of goal setting, and satisfaction with the active rehabilitation programme. Topics of discussion highlighted in red present a potentially negative experience. These include information such as COVID-19 and the political atmosphere as well as exercise tolerance, progression, and motivation. Topics of discussion highlighted in yellow presented points that were not clearly linked to a positive or negative experience (e.g., weather, unclear or neutral feelings, and preferences).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302260.g008