- Previous Article

- Next Article

Case Presentation

Case study: a patient with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and complex comorbidities whose diabetes care is managed by an advanced practice nurse.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Geralyn Spollett; Case Study: A Patient With Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes and Complex Comorbidities Whose Diabetes Care Is Managed by an Advanced Practice Nurse. Diabetes Spectr 1 January 2003; 16 (1): 32–36. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.16.1.32

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The specialized role of nursing in the care and education of people with diabetes has been in existence for more than 30 years. Diabetes education carried out by nurses has moved beyond the hospital bedside into a variety of health care settings. Among the disciplines involved in diabetes education, nursing has played a pivotal role in the diabetes team management concept. This was well illustrated in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) by the effectiveness of nurse managers in coordinating and delivering diabetes self-management education. These nurse managers not only performed administrative tasks crucial to the outcomes of the DCCT, but also participated directly in patient care. 1

The emergence and subsequent growth of advanced practice in nursing during the past 20 years has expanded the direct care component, incorporating aspects of both nursing and medical care while maintaining the teaching and counseling roles. Both the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and nurse practitioner (NP) models, when applied to chronic disease management, create enhanced patient-provider relationships in which self-care education and counseling is provided within the context of disease state management. Clement 2 commented in a review of diabetes self-management education issues that unless ongoing management is part of an education program, knowledge may increase but most clinical outcomes only minimally improve. Advanced practice nurses by the very nature of their scope of practice effectively combine both education and management into their delivery of care.

Operating beyond the role of educator, advanced practice nurses holistically assess patients’ needs with the understanding of patients’ primary role in the improvement and maintenance of their own health and wellness. In conducting assessments, advanced practice nurses carefully explore patients’ medical history and perform focused physical exams. At the completion of assessments, advanced practice nurses, in conjunction with patients, identify management goals and determine appropriate plans of care. A review of patients’ self-care management skills and application/adaptation to lifestyle is incorporated in initial histories, physical exams, and plans of care.

Many advanced practice nurses (NPs, CNSs, nurse midwives, and nurse anesthetists) may prescribe and adjust medication through prescriptive authority granted to them by their state nursing regulatory body. Currently, all 50 states have some form of prescriptive authority for advanced practice nurses. 3 The ability to prescribe and adjust medication is a valuable asset in caring for individuals with diabetes. It is a crucial component in the care of people with type 1 diabetes, and it becomes increasingly important in the care of patients with type 2 diabetes who have a constellation of comorbidities, all of which must be managed for successful disease outcomes.

Many studies have documented the effectiveness of advanced practice nurses in managing common primary care issues. 4 NP care has been associated with a high level of satisfaction among health services consumers. In diabetes, the role of advanced practice nurses has significantly contributed to improved outcomes in the management of type 2 diabetes, 5 in specialized diabetes foot care programs, 6 in the management of diabetes in pregnancy, 7 and in the care of pediatric type 1 diabetic patients and their parents. 8 , 9 Furthermore, NPs have also been effective providers of diabetes care among disadvantaged urban African-American patients. 10 Primary management of these patients by NPs led to improved metabolic control regardless of whether weight loss was achieved.

The following case study illustrates the clinical role of advanced practice nurses in the management of a patient with type 2 diabetes.

A.B. is a retired 69-year-old man with a 5-year history of type 2 diabetes. Although he was diagnosed in 1997, he had symptoms indicating hyperglycemia for 2 years before diagnosis. He had fasting blood glucose records indicating values of 118–127 mg/dl, which were described to him as indicative of “borderline diabetes.” He also remembered past episodes of nocturia associated with large pasta meals and Italian pastries. At the time of initial diagnosis, he was advised to lose weight (“at least 10 lb.”), but no further action was taken.

Referred by his family physician to the diabetes specialty clinic, A.B. presents with recent weight gain, suboptimal diabetes control, and foot pain. He has been trying to lose weight and increase his exercise for the past 6 months without success. He had been started on glyburide (Diabeta), 2.5 mg every morning, but had stopped taking it because of dizziness, often accompanied by sweating and a feeling of mild agitation, in the late afternoon.

A.B. also takes atorvastatin (Lipitor), 10 mg daily, for hypercholesterolemia (elevated LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated triglycerides). He has tolerated this medication and adheres to the daily schedule. During the past 6 months, he has also taken chromium picolinate, gymnema sylvestre, and a “pancreas elixir” in an attempt to improve his diabetes control. He stopped these supplements when he did not see any positive results.

He does not test his blood glucose levels at home and expresses doubt that this procedure would help him improve his diabetes control. “What would knowing the numbers do for me?,” he asks. “The doctor already knows the sugars are high.”

A.B. states that he has “never been sick a day in my life.” He recently sold his business and has become very active in a variety of volunteer organizations. He lives with his wife of 48 years and has two married children. Although both his mother and father had type 2 diabetes, A.B. has limited knowledge regarding diabetes self-care management and states that he does not understand why he has diabetes since he never eats sugar. In the past, his wife has encouraged him to treat his diabetes with herbal remedies and weight-loss supplements, and she frequently scans the Internet for the latest diabetes remedies.

During the past year, A.B. has gained 22 lb. Since retiring, he has been more physically active, playing golf once a week and gardening, but he has been unable to lose more than 2–3 lb. He has never seen a dietitian and has not been instructed in self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG).

A.B.’s diet history reveals excessive carbohydrate intake in the form of bread and pasta. His normal dinners consist of 2 cups of cooked pasta with homemade sauce and three to four slices of Italian bread. During the day, he often has “a slice or two” of bread with butter or olive oil. He also eats eight to ten pieces of fresh fruit per day at meals and as snacks. He prefers chicken and fish, but it is usually served with a tomato or cream sauce accompanied by pasta. His wife has offered to make him plain grilled meats, but he finds them “tasteless.” He drinks 8 oz. of red wine with dinner each evening. He stopped smoking more than 10 years ago, he reports, “when the cost of cigarettes topped a buck-fifty.”

The medical documents that A.B. brings to this appointment indicate that his hemoglobin A 1c (A1C) has never been <8%. His blood pressure has been measured at 150/70, 148/92, and 166/88 mmHg on separate occasions during the past year at the local senior center screening clinic. Although he was told that his blood pressure was “up a little,” he was not aware of the need to keep his blood pressure ≤130/80 mmHg for both cardiovascular and renal health. 11

A.B. has never had a foot exam as part of his primary care exams, nor has he been instructed in preventive foot care. However, his medical records also indicate that he has had no surgeries or hospitalizations, his immunizations are up to date, and, in general, he has been remarkably healthy for many years.

Physical Exam

A physical examination reveals the following:

Weight: 178 lb; height: 5′2″; body mass index (BMI): 32.6 kg/m 2

Fasting capillary glucose: 166 mg/dl

Blood pressure: lying, right arm 154/96 mmHg; sitting, right arm 140/90 mmHg

Pulse: 88 bpm; respirations 20 per minute

Eyes: corrective lenses, pupils equal and reactive to light and accommodation, Fundi-clear, no arteriolovenous nicking, no retinopathy

Thyroid: nonpalpable

Lungs: clear to auscultation

Heart: Rate and rhythm regular, no murmurs or gallops

Vascular assessment: no carotid bruits; femoral, popliteal, and dorsalis pedis pulses 2+ bilaterally

Neurological assessment: diminished vibratory sense to the forefoot, absent ankle reflexes, monofilament (5.07 Semmes-Weinstein) felt only above the ankle

Lab Results

Results of laboratory tests (drawn 5 days before the office visit) are as follows:

Glucose (fasting): 178 mg/dl (normal range: 65–109 mg/dl)

Creatinine: 1.0 mg/dl (normal range: 0.5–1.4 mg/dl)

Blood urea nitrogen: 18 mg/dl (normal range: 7–30 mg/dl)

Sodium: 141 mg/dl (normal range: 135–146 mg/dl)

Potassium: 4.3 mg/dl (normal range: 3.5–5.3 mg/dl)

Lipid panel

• Total cholesterol: 162 mg/dl (normal: <200 mg/dl)

• HDL cholesterol: 43 mg/dl (normal: ≥40 mg/dl)

• LDL cholesterol (calculated): 84 mg/dl (normal: <100 mg/dl)

• Triglycerides: 177 mg/dl (normal: <150 mg/dl)

• Cholesterol-to-HDL ratio: 3.8 (normal: <5.0)

AST: 14 IU/l (normal: 0–40 IU/l)

ALT: 19 IU/l (normal: 5–40 IU/l)

Alkaline phosphotase: 56 IU/l (normal: 35–125 IU/l)

A1C: 8.1% (normal: 4–6%)

Urine microalbumin: 45 mg (normal: <30 mg)

Based on A.B.’s medical history, records, physical exam, and lab results, he is assessed as follows:

Uncontrolled type 2 diabetes (A1C >7%)

Obesity (BMI 32.4 kg/m 2 )

Hyperlipidemia (controlled with atorvastatin)

Peripheral neuropathy (distal and symmetrical by exam)

Hypertension (by previous chart data and exam)

Elevated urine microalbumin level

Self-care management/lifestyle deficits

• Limited exercise

• High carbohydrate intake

• No SMBG program

Poor understanding of diabetes

A.B. presented with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and a complex set of comorbidities, all of which needed treatment. The first task of the NP who provided his care was to select the most pressing health care issues and prioritize his medical care to address them. Although A.B. stated that his need to lose weight was his chief reason for seeking diabetes specialty care, his elevated glucose levels and his hypertension also needed to be addressed at the initial visit.

The patient and his wife agreed that a referral to a dietitian was their first priority. A.B. acknowledged that he had little dietary information to help him achieve weight loss and that his current weight was unhealthy and “embarrassing.” He recognized that his glucose control was affected by large portions of bread and pasta and agreed to start improving dietary control by reducing his portion size by one-third during the week before his dietary consultation. Weight loss would also be an important first step in reducing his blood pressure.

The NP contacted the registered dietitian (RD) by telephone and referred the patient for a medical nutrition therapy assessment with a focus on weight loss and improved diabetes control. A.B.’s appointment was scheduled for the following week. The RD requested that during the intervening week, the patient keep a food journal recording his food intake at meals and snacks. She asked that the patient also try to estimate portion sizes.

Although his physical activity had increased since his retirement, it was fairly sporadic and weather-dependent. After further discussion, he realized that a week or more would often pass without any significant form of exercise and that most of his exercise was seasonal. Whatever weight he had lost during the summer was regained in the winter, when he was again quite sedentary.

A.B.’s wife suggested that the two of them could walk each morning after breakfast. She also felt that a treadmill at home would be the best solution for getting sufficient exercise in inclement weather. After a short discussion about the positive effect exercise can have on glucose control, the patient and his wife agreed to walk 15–20 minutes each day between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m.

A first-line medication for this patient had to be targeted to improving glucose control without contributing to weight gain. Thiazolidinediones (i.e., rosiglitizone [Avandia] or pioglitizone [Actos]) effectively address insulin resistance but have been associated with weight gain. 12 A sulfonylurea or meglitinide (i.e., repaglinide [Prandin]) can reduce postprandial elevations caused by increased carbohydrate intake, but they are also associated with some weight gain. 12 When glyburide was previously prescribed, the patient exhibited signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia (unconfirmed by SMBG). α-Glucosidase inhibitors (i.e., acarbose [Precose]) can help with postprandial hyperglycemia rise by blunting the effect of the entry of carbohydrate-related glucose into the system. However, acarbose requires slow titration, has multiple gastrointestinal (GI) side effects, and reduces A1C by only 0.5–0.9%. 13 Acarbose may be considered as a second-line therapy for A.B. but would not fully address his elevated A1C results. Metformin (Glucophage), which reduces hepatic glucose production and improves insulin resistance, is not associated with hypoglycemia and can lower A1C results by 1%. Although GI side effects can occur, they are usually self-limiting and can be further reduced by slow titration to dose efficacy. 14

After reviewing these options and discussing the need for improved glycemic control, the NP prescribed metformin, 500 mg twice a day. Possible GI side effects and the need to avoid alcohol were of concern to A.B., but he agreed that medication was necessary and that metformin was his best option. The NP advised him to take the medication with food to reduce GI side effects.

The NP also discussed with the patient a titration schedule that increased the dosage to 1,000 mg twice a day over a 4-week period. She wrote out this plan, including a date and time for telephone contact and medication evaluation, and gave it to the patient.

During the visit, A.B. and his wife learned to use a glucose meter that features a simple two-step procedure. The patient agreed to use the meter twice a day, at breakfast and dinner, while the metformin dose was being titrated. He understood the need for glucose readings to guide the choice of medication and to evaluate the effects of his dietary changes, but he felt that it would not be “a forever thing.”

The NP reviewed glycemic goals with the patient and his wife and assisted them in deciding on initial short-term goals for weight loss, exercise, and medication. Glucose monitoring would serve as a guide and assist the patient in modifying his lifestyle.

A.B. drew the line at starting an antihypertensive medication—the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril (Vasotec), 5 mg daily. He stated that one new medication at a time was enough and that “too many medications would make a sick man out of me.” His perception of the state of his health as being represented by the number of medications prescribed for him gave the advanced practice nurse an important insight into the patient’s health belief system. The patient’s wife also believed that a “natural solution” was better than medication for treating blood pressure.

Although the use of an ACE inhibitor was indicated both by the level of hypertension and by the presence of microalbuminuria, the decision to wait until the next office visit to further evaluate the need for antihypertensive medication afforded the patient and his wife time to consider the importance of adding this pharmacotherapy. They were quite willing to read any materials that addressed the prevention of diabetes complications. However, both the patient and his wife voiced a strong desire to focus their energies on changes in food and physical activity. The NP expressed support for their decision. Because A.B. was obese, weight loss would be beneficial for many of his health issues.

Because he has a sedentary lifestyle, is >35 years old, has hypertension and peripheral neuropathy, and is being treated for hypercholestrolemia, the NP performed an electrocardiogram in the office and referred the patient for an exercise tolerance test. 11 In doing this, the NP acknowledged and respected the mutually set goals, but also provided appropriate pre-exercise screening for the patient’s protection and safety.

In her role as diabetes educator, the NP taught A.B. and his wife the importance of foot care, demonstrating to the patient his inability to feel the light touch of the monofilament. She explained that the loss of protective sensation from peripheral neuropathy means that he will need to be more vigilant in checking his feet for any skin lesions caused by poorly fitting footwear worn during exercise.

At the conclusion of the visit, the NP assured A.B. that she would share the plan of care they had developed with his primary care physician, collaborating with him and discussing the findings of any diagnostic tests and procedures. She would also work in partnership with the RD to reinforce medical nutrition therapies and improve his glucose control. In this way, the NP would facilitate the continuity of care and keep vital pathways of communication open.

Advanced practice nurses are ideally suited to play an integral role in the education and medical management of people with diabetes. 15 The combination of clinical skills and expertise in teaching and counseling enhances the delivery of care in a manner that is both cost-reducing and effective. Inherent in the role of advanced practice nurses is the understanding of shared responsibility for health care outcomes. This partnering of nurse with patient not only improves care but strengthens the patient’s role as self-manager.

Geralyn Spollett, MSN, C-ANP, CDE, is associate director and an adult nurse practitioner at the Yale Diabetes Center, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. She is an associate editor of Diabetes Spectrum.

Note of disclosure: Ms. Spollett has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Aventis and has been a paid consultant for Aventis. Both companies produce products and devices for the treatment of diabetes.

Email alerts

- Advanced Practice Care: Advanced Practice Care in Diabetes: Epilogue

- Advanced Practice Care: Advanced Practice Care in Diabetes: Preface

- Online ISSN 1944-7353

- Print ISSN 1040-9165

- Diabetes Care

- Clinical Diabetes

- Diabetes Spectrum

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes

- Scientific Sessions Abstracts

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care

- ShopDiabetes.org

- ADA Professional Books

Clinical Compendia

- Clinical Compendia Home

- Latest News

- DiabetesPro SmartBrief

- Special Collections

- DiabetesPro®

- Diabetes Food Hub™

- Insulin Affordability

- Know Diabetes By Heart™

- About the ADA

- Journal Policies

- For Reviewers

- Advertising in ADA Journals

- Reprints and Permission for Reuse

- Copyright Notice/Public Access Policy

- ADA Professional Membership

- ADA Member Directory

- Diabetes.org

- X (Twitter)

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

- © Copyright American Diabetes Association

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

The patient has been treated for hypertension for 10 years, currently with amlodipine 10 mg by mouth daily. She was once told that her cholesterol value was "borderline high" but does not know the value.

She denies symptoms of diabetes, chest pain, shortness of breath, heart disease, stroke, or circulatory problems of the lower extremities.

She estimates her current weight at 165 lbs (75 kg). She thinks she weighed 120 lbs (54 kg) at age 21 years but gained weight with each of her three pregnancies and did not return to her nonpregnant weight after each delivery. She weighed 155 lbs one year ago but gained weight following retirement from her job as an elementary school teacher. No family medical history is available because she was adopted. She does not eat breakfast, has a modest lunch, and consumes most of her calories at supper and in the evening.

On examination, blood pressure is 140/85 mmHg supine and 140/90 mmHg upright with a regular heart rate of 76 beats/minute. She weighs 169 lbs, with a body mass index (BMI) of 30.9 kg/m 2 . Fundoscopic examination reveals no evidence of retinopathy. Vibratory sensation is absent at the great toes, reduced at the medial malleoli, and normal at the tibial tubercles. Light touch sensation is reduced in the feet but intact more proximally. Knee jerks are 2+ bilaterally, but the ankle jerks are absent. The examination is otherwise within normal limits.

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Email Address *

- Living with and/or caring for someone with type 2 diabetes

- A medical professional caring for those with type 2 diabetes

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Home

- Health Professional Topics

- CVD Risk Reduction

- Managing Sterling’s Journey: A T2D and CVD Case Study

CVD Case Studies

Know diabetes and cvd.

During this poster series, manage a patient’s journey as he meets with his physician who assesses his health issues and develops a treatment plan for him to follow. Follow this interactive case study of diabetes and CVD and click each poster below and learn how different factors, such as medication adherence and lifestyle interventions affect Sterling’s glycemic control, CVD risk management and overall outcomes. (Content accurate as of May 2023).

Meet Sterling

Sterling has a new problem

Discuss Sterling’s treatment plan

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER

Founding sponsor.

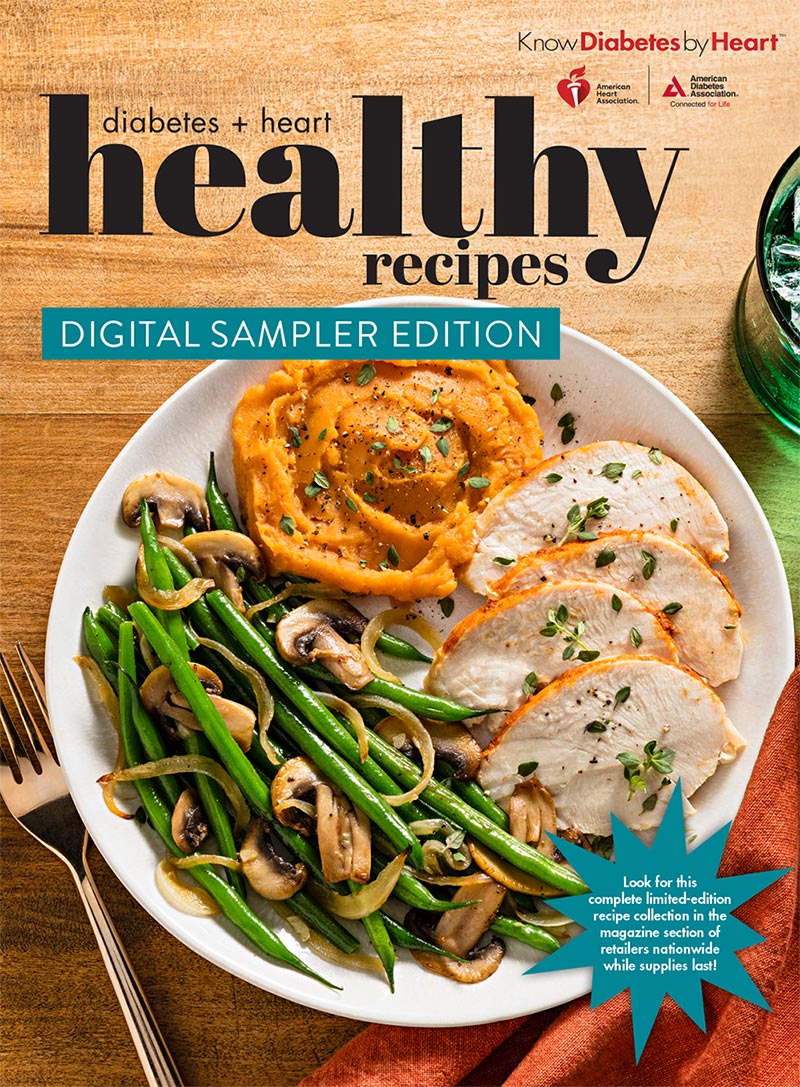

FREE mini cookbook!

Plus monthly diabetes tips to take care of your heart

Instant access

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Obes Metab Syndr

- v.26(1); 2017 Mar

Two Cases of Successful Type 2 Diabetes Control with Lifestyle Modification in Children and Adolescents

Seon hwa lee.

1 Department of Pediatrics, Konkuk University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

Myung Hyun Cho

Yong hyuk kim.

2 Department of Pediatrics, Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea

Sochung Chung

Obesity and obesity-related disease are becoming serious global issues. The incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes has increased in children and adolescents. Type 2 diabetes is a chronic disease that is difficult to treat, and the accurate assessment of obesity in type 2 diabetes is becoming increasingly important. Obesity is the excessive accumulation of fat that causes insulin resistance, and body composition analyses can help physicians evaluate fat levels. Although previous studies have shown the achievement of complete remission of type 2 diabetes after focused improvement in lifestyle habits, there are few cases of complete remission of type 2 diabetes. Here we report on obese patients with type 2 diabetes who were able to achieve considerable fat loss and partial or complete remission of diabetes through lifestyle changes. This case report emphasizes once again that focused lifestyle intervention effectively treats childhood diabetes.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity and obesity-related diseases are serious public health issues worldwide, and the increased incidence of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents is associated with the increased incidence of obesity. 1 , 2 Excess weight gain is a risk factor for both type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance. Obesity refers to excessive fat accumulation and may affect the clinical course of diabetes in terms of insulin resistance. Therefore, the accurate assessment of obesity is important. 3 Body mass index (BMI) is used as an indicator to evaluate weight excess or obesity. 4 However, BMI is limited in that it is the sum of fat-free mass index (FFMI) and fat mass index (FMI) and does not only reflect excess fat. 5 , 6 Therefore, it may be helpful to use body composition analysis that measures fat mass (FM) without fat-free mass (FFM) as a tool to evaluate obesity. Although type 2 diabetes is considered a chronic disease that is difficult to completely cure 7 , 8 , studies have reported complete remission of type 2 diabetes in adults after intensive lifestyle modification. 9 Here we report two cases of type 2 diabetes with partial or complete response to lifestyle modification, particularly FM decrease. Our findings emphasize that lifestyle modifications including dietary treatment and exercise therapy comprise the first-line treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. 10

CASE REPORT

Ms. L, 17 years and 5 months, female

Polydipsia, polyuria

Family history

Mother with hypertension, father with heart failure.

Past medical/social history

No significant history

History of present illness

This 17-year-old girl was diagnosed with diabetes at another hospital after a 1-month history of persistent polydipsia and polyuria. She presented to Konkuk University Medical Center for further diagnosis and treatment of her persistent symptoms.

Physical examination

On admission, her height was 173.1 cm (>97th percentile), weight was 107.2 kg (>97th percentile), and BMI was 35.8 kg/m 2 (>97th percentile) ( Table 1 ). She appeared obese but did not look ill and her mental status was intact. Her vital signs were normal except for a blood pressure of 137/81 mmHg (95–99th percentile). Her skin was warm and no dry mucous membranes were observed. A chest examination was unremarkable. No enlargement of the liver or spleen was appreciated on an abdominal examination. The rest of the physical exam was unremarkable.

Anthropometric data and patient body composition profiles of adolescent girls with type 2 diabetes who achieved remission after stopping medications

BMI, body mass index; FFM, fat free mass; FM, fat mass; FFMI, fat free mass index; FMI, fat mass index; FFMIZ, fat free mass index Z score; FMIZ, fat mass index Z score; PBF, percent body fat.

Lab findings

Labs on admission revealed a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 11.1%, fasting plasma glucose level of 102 mg/dL, insulin level of 23.12 μIU/mL, and C-peptide level of 4.13 ng/mL. Liver function tests revealed an elevated serum aspartate transaminase (AST) level of 115 IU/L and serum alanine transaminase (ALT) level of 141 IU/L. A lipid panel demonstrated a total cholesterol level of 133 mg/dL, triglycerides of 71 mg/dL, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) of 49 mg/dL ( Table 2 ). The total protein and albumin level was 7.0 g/dL and that of albumin was 4.5 g/dL. The free fatty acid level was elevated at 1214 μEq/L.

Biochemical profiles of adolescent girls with type 2 diabetes who achieved remission after stopping medications

HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high lipoprotein; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

Radiologic findings

There were no abnormal findings on a chest radiograph. An abdominal ultrasound showed severe fatty infiltration of the liver.

Treatment and progress

For glycemic control, the patient was started on oral medications (metformin 500 mg BID, glimepiride 1 mg QD) as well as a diet and exercise program as a lifestyle modification. Her dietary and nutritional knowledge were evaluated, and she was counseled to have regular meals with 70–75 g of proteins per day and maintain daily nutritional requirements of approximately 1,800 kcal. She was recommended to consume a low-carb, low-fat diet, limit high saturated fats, track her intake, and attend outpatient appointments every 1–2 months. She was instructed to perform aerobic and weight exercises that improve muscle strength for more than 1 hour at least 3 times per week. For 1 year, she did aerobic and anaerobic exercises for an hour or more per day. After 1 year, she incorporated a 7 km walk daily and Pilates more than 3 times per week to her exercise program. In the outpatient setting, we assessed her adherence to therapy at 1–2 month intervals, offered motivational support, and advised her to gradually increase her exercise duration rather than intensity. We measured her height and weight every year and used InBody720, a type of bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), to accurately evaluate her obesity. On diagnosis, the patient’s BMI was 35.8 kg/m 2 (FMI, 18.0 kg/m 2 ; FFMI, 17.8 kg/m 2 ), scoring >97th percentile, and percent body fat (PBF) was 50.4%. During the 2 years of outpatient monitoring, she had no difficulty controlling her blood sugar level using the combination of oral medication and lifestyle modification. However, the dose of metformin was increased to 1,000 mg BID due to difficulty maintaining her HbA1c <7.0% on the previous regimen; at that time, she was still considered obese with a BMI of 35.1 kg/m 2 (FMI, 17.2 kg/m 2 ; FFMI, 17.9 kg/m 2 ) and PBF of 48.9%. Her weight and body composition during treatment are shown in Fig. 1 .

Plot of changes in FFMI and FMI in two adolescent girls with T2DM who achieved remission. T2DM, type 2 diabetes; BMI, body mass index; PBF, percent body fat; FFMI, fat free mass index; FMI, fat mass index.

Three years later, the patient’s dietary therapy and exercise program resulted in an increased FFMI at 18.3 kg/m 2 and reduced FMI at 14.9 kg/m 2 , leading to discontinuation of the glimepiride and a reduction in the metformin dose to 500 mg BID.

Four years later, her HbA1c decreased to 5.4% and the metformin was discontinued due to her successful glycemic control. At that time, her fasting blood glucose level was 97 mg/dL, insulin level was 5.62 μIU/mL, and C-peptide level was 2.13 ng/mL. Her BMI was 27.1 kg/m 2 (FMI, 10.3 kg/m 2 ; FFMI, 16.8 kg/m 2 ) and PBF was 38.2%, which is still considered obese based on the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for Asian adults; however, it was 8.7 kg/m 2 less than her BMI prior to treatment and her FMI had decreased by 7.7 kg/m 2 . Her FFMI was also reduced by 1.0 kg/m 2 , but still belonged to the 90–95th percentile; thus, her nutritional status was not a concern ( Table 1 ). Liver function tests and a lipid panel revealed AST 20 IU/L, ALT 12 IU/L, total cholesterol 114 mg/dL, triglycerides 59 mg/dL, and HDL-C 51 mg/dL ( Table 2 ). Her HbA1c has remained at <5.7% for more than a year without oral medications and will continue to be followed.

Ms. A, 12 years and 10 months, female

Hyperglycemia

Father with type 2 diabetes under treatment

12-year-old female who presented to Konkuk University Medical Center with post-prandial hyperglycemia of 330 mg/dL measured by her father one day prior to admission. Menarche occurred 1 year prior and her menstrual cycles were regular.

On admission, the patient’s height was 158.9 cm (25–50th percentile), weight was 75.5 kg (>97th percentile), and BMI was 29.9 kg/m 2 (>97th percentile) ( Table 1 ). Her vital signs were within the normal range with a blood pressure of 112/68 mmHg, pulse of 72 beats/min, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and temperature of 36.6°C. She had a clear mental status, warm skin, and moist mucous membranes. A chest examination revealed no specific findings, while an abdominal examination revealed no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory findings

Laboratory tests at the time of admission revealed an HbA1c level of 9.9%, fasting blood glucose level of 202 mg/dL, insulin level of 15.85 μIU/mL, and C-peptide level of 2.97 ng/mL. Liver function tests showed an elevated AST level at 47 IU/L and ALT level at 69 IU/L. A lipid panel and comprehensive metabolic panel showed a total cholesterol level of 165 mg/dL, triglyceride level of 104 mg/dL, HDL-C of 50 mg/dL, total protein of 7.6 g/dL, and albumin of 4.8 g/dL ( Table 2 ). The free fatty acid level was elevated at 671 μEq/L.

Radiologic finding

There were no significant findings on a chest radiograph. An abdominal ultrasound showed moderate fatty liver.

For glycemic control, combination therapy of oral medication (metformin 500 mg BID) and lifestyle modification through adjustments in dietary habits was prescribed. We evaluated her dietary and nutritional knowledge and then counseled her to consume regular meals with 70–90 g of protein per day, maintain daily nutritional requirements of approximately 1800 kcal, and eat a low-carb, low-fat diet. She was recommended to modify her habitual preference of salty and spicy foods, reduce her salt intake, track her meals, and attend outpatient monitoring appointments every 1–2 months.

For an exercise program, she was instructed to include aerobic and weight exercises that improve muscle strength. She was advised to walk >1 hour at least 5 days per week and visit a health training center for ≥1 hour of strength exercises at least 3 times per week. We measured her height and weight every 2 months, and used InBody720, a type of BIA for accurate assessment of obesity. On diagnosis, patient’s BMI was 29.9 kg/m 2 (FMI, 12.7 kg/m 2 ; FFMI, 17.2 kg/m 2 ) and PBF was 42.5%. Two years later after the diagnosis, an abdominal ultrasound showed improvements in her fatty liver and her HbA1c was successfully reduced to 6.0%. The oral medication was discontinued due to the successful glycemic control. At the time, her fasting blood sugar was 97 mg/dL, insulin level was 5.62 μIU/mL, and C-peptide level was 2.79 ng/mL. Her BMI (FMI+FFMI) was 23.2 kg/m 2 (7.0 kg/m 2 +16.2 kg/m 2 ), which was within the overweight range (85–90th percentile), and her PBF was 30.2%. Her BMI at that point was 6.7 kg/m 2 lower than that prior to therapy, with a 5.7 kg/m 2 reduction observed in her FMI ( Table 1 ). Liver function tests and a lipid panel revealed the following: AST, 20 IU/L; ALT, 34 IU/L; total cholesterol, 115 mg/dL; triglycerides, 70 mg/dL; and HDL-C, 30 mg/dL ( Table 2 ). The changes in the patient’s weight and body composition during treatment are shown in Fig. 1 . Since discontinuing the oral medication, the patient has maintained an HbA1c level <6.5%.

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing with changes in dietary habits and increases in the incidence of obesity among children and adolescents. Although it is already known that a reduced caloric intake and weight loss through lifestyle modifications can treat diabetes, few cases demonstrating such an effect have been reported to date. 9 As discussed previously in two cases, a notable reduction in FM resulted in an HbA1c level <6.5% and improved glycemic control as well as successful maintenance of HbA1c at goal level without medications. According to the 2009 consensus statement reported by the American Diabetes Association, a complete response is defined as blood sugar in the normal range for >1 year without any medications (fasting blood sugar <100 mg/dL, HbA1c <5.7%). Partial response is defined as a blood sugar level below the diabetes range for >1 year without any medications or medical procedures (HbA1C <6.5%; fasting blood sugar, 100–125 mg/dL). 11 In the two cases presented above, significant decreases in BMI and PBF were observed as well as subsequent improvements in HbA1c and fasting blood sugar level. In developing children, weight gain occurs with increasing age, and increases in BMI are common. However, such increases in BMI are due to increases in FFM, not FM. 6 Appropriate growth is one of the important objectives of pediatric diabetes management and treatment. Since proper nutrition and hormonal balance are essential for growth, it is more important to achieve a reduction in FM than a reduction in weight by having regular meals that are low in carbs and fat with a normal protein intake.

Weight loss through lifestyle modification generally affects FFM. In the cases discussed above, both patients had elevated FM and FFM on admission. By balancing appropriate dietary changes with aerobic and anaerobic exercises, the patient was able to maintain FFM and incur no significant effect on growth. In the present case, the patient was instructed to spend 1 hour exercising at least 3 times per week, assessed for compliance as an outpatient every 1–2 months, offered continuous motivational support, and told to gradually increase her exercise duration.

A recent study reported that oral medication was eventually needed to control hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes refractory to management with proper lifestyle modification. 12 However, lifestyle modification is important, and is a cornerstone in the treatment of diabetes, and it should be a mandatory treatment for type 2 diabetes. In females, it is common to see an increase in PBF with progression of puberty. 13 , 14 However, here we report cases of complete remission of diabetes in teenage girls with lifestyle modification and emphasize once again that intensive lifestyle improvement is an effective early treatment for diabetes. 15

Our results demonstrate that intensive lifestyle modification including regular exercise and dietary changes is very effective in the treatment of obese patients with type 2 diabetes.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

CC, History, and PE

Chief Concern

“I feel so tired lately and can’t seem to shake this sinus infection.”

History of Present Illness

Ms. Yazzie, a 63 year old Navajo female and long-time patient of your primary care office presents today with concerns related to general fatigue and ongoing sinusitis-like symptoms. She states that while her symptoms are “not so serious,” she has grown “sick and tired of being sick and tired.” Over the last four or five months Ms. Yazzie has grown fatigued and weak at times, as well as having symptoms of sinusitis and two back-to-back yeast infections. She recently bought a water bottle because she noticed she was thirsty “all the time.”

Two years ago, at a routine screening you diagnosed Ms. Yazzie as pre-diabetic. At that time, she appeared motivated to make lifestyle changes. She states that shortly after that appointment her sister fell ill and she moved back to the Navajo Nation to care for her. The last two years Ms. Yazzie has been dedicated to caring for her sister and sorting out her sister’s affairs since she passed. Ms. Yazzie states that she did not have time to take “good care of herself.” She says healthcare on the reservation was not easily accessible or of high quality and that exercise and a balanced diet were not priorities.

Past Medical History

- Pre-diabetes: age 61

- Hypertension: age 52

- Hyperlipidemia: age 49

- Obesity: age 38

- Varicella: 8

Medications

Ms. Yazzie is not currently taking any medications but she previously had the following medications:

- Bumex 0.5 mg po BID

- Zocor 40 mg po daily

Family History

Both of Ms. Yazzie’s parents are dead. Her father died of a heart attack when he was 52 years old. Ms. Yazzie does not know much about his health because he, “didn’t like going to the doctor.” Her mother died fifteen years ago at the age of 71. Ms. Yazzie’s mother had type 2 diabetes mellitus and well-controlled hypertension.

Ms. Yazzie’s sister died at age 64, the specific cause is unknown. She had been diagnosed with obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and suspected coronary artery disease.

Ms. Yazzie’s other sister is alive at age 59. She was diagnosed with obesity at age 37 and hypertension at age 49.

Social History

Ms. Yazzie lives alone in a one bedroom apartment. Prior to moving to Arizona she worked as an artist’s assistant and docent at the art museum. She is currently volunteering again at the museum and looking for work.

She was married for 12 years but divorced nearly 30 years ago. Ms. Yazzie has one son who lives in town: she helps care for his three teenage children.

Ms. Yazzie denies drinking alcohol but says she smokes cigarettes. She says she’s been a smoker since she was 17 and smokes about a half pack a day (22 pack years).

Focused Physical Exam

- VS: HR – 85, RR – 16, Temp – 94.3, BP – 136/86, O2 – 99% on room air

- General: A&Ox4, appearance appropriate for age and race, central obesity (waist diameter 38”)

- Skin: cool and dry. A 2” abrasion on right ankle that the patient says, “just won’t heal.”

- HEENT: patient notes some floaters in her right eye “recently.”

- GU: recent yeast infections, polyuria

- GI: active bowel sounds in all quadrants

- Respiratory: clear breath sounds in all fields

- Cardiac: clear S1 and S2 noted. Absence of any murmur or rub.

You ask Ms. Yazzie to come back in for some diabetes-related diagnostic tests and a lipid profile over the following two weeks.

- Fasting blood glucose: 145 mg/dL first test; 138 mg/dL second test

- Glucose tolerance test: 212 mg/dL; 222 mg/dL second test

- HbA1c: 6.5%

- Triglycerides: 168 mg/dL

- HDL: 46 mg/dL

- LDL: 174 mg/dL

- Total: 220 mg/dL

Photo from Healthline

Clinical validity of the nursing diagnosis risk for unstable blood glucose level in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A case-control study

Affiliations.

- 1 Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira, Redenção, Brazil.

- 2 Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 3 Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

- PMID: 38801733

- DOI: 10.1111/2047-3095.12475

Abstract in English, Portuguese

Objective: To assess clinical-causal validity evidence of the nursing diagnosis, risk for unstable blood glucose level (00179), in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods: A case-control study was conducted in 5 primary healthcare units, involving 107 subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus, 60 in the case group and 47 in the control group. Causality was determined by the association between sociodemographic and clinical factors, risk factors related to the nursing diagnosis, and the occurrence of unstable blood glucose level. An association was considered when the risk factor had a p-value of <0.05 and odds ratio >1.

Results: Risk factors, such as stress, inadequate physical activity, and low adherence to therapeutic regimen, were prevalent in the sample. Time since diagnosis between 1-5 and 6-10 years, multiracial ethnicity, and the risk factor of low adherence to therapeutic regimen increased the likelihood of the outcome. Completion of high school education was identified as a protective factor.

Conclusions: The clinical validation of the nursing diagnosis, risk for unstable blood glucose level, has been successfully established, revealing a clear association between sociodemographic and clinical factors and the risk factors inherent to the nursing diagnosis.

Implications for nursing practice: The results contribute to advancing scientific knowledge related to nursing education, research, and practice and provide support for the evolution of nursing care processes for individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Objetivo: Avaliar a evidência de validade clínico‐causal do diagnóstico de enfermagem, risco para nível instável de glicose no sangue (00179), em indivíduos com diabetes mellitus tipo 2. MÉTODO: Foi realizado um estudo caso‐controle em cinco unidades básicas de saúde, envolvendo 107 indivíduos com diabetes mellitus tipo 2, 60 no grupo caso e 47 no grupo controle. A causalidade foi determinada pela associação entre fatores sociodemográficos e clínicos, fatores de risco relacionados ao diagnóstico de enfermagem e a ocorrência de nível instável de glicose no sangue. Uma associação foi considerada quando o fator de risco tinha um valor de p < 0.05 e odds ratio > 1.

Resultados: Fatores de risco como estresse, atividade física inadequada e baixa adesão ao regime terapêutico foram predominantes na amostra. O tempo desde o diagnóstico entre 1 e 5 anos e 6 a 10 anos, a etnia parda e o fator de risco baixa adesão ao regime terapêutico aumentaram a probabilidade do resultado. A conclusão do ensino médio foi identificada como um fator de proteção. CONCLUSÕES: A validação clínica do diagnóstico de enfermagem, risco para nível instável de glicose no sangue, foi estabelecida com sucesso, revelando uma clara associação entre fatores sociodemográficos e clínicos e os fatores de risco inerentes ao diagnóstico de enfermagem. IMPLICAÇÕES PARA A PRÁTICA DE ENFERMAGEM: Os resultados contribuem para o avanço do conhecimento científico relacionado à educação, à pesquisa e à prática de enfermagem e fornecem suporte para a evolução dos processos de cuidados de enfermagem para indivíduos com diabetes.

Keywords: case–control studies; glycemic control; nursing diagnosis; type 2 diabetes mellitus.

© 2024 NANDA International, Inc.

- Diabetes & Primary Care

- Vol:23 | No:01

Interactive case study: Type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy

- 23 Feb 2021

Share this article + Add to reading list – Remove from reading list ↓ Download pdf

The new series of case studies from Diabetes & Primary Care is aimed at GPs, practice nurses and other professionals in primary and community care who would like to broaden their understanding of type 2 diabetes. This second case study takes you through the necessary considerations in diagnosing and managing diabetic nephropathy in an individual with type 2 diabetes.

The format uses a typical clinical scenario as a tool for learning. Information is provided in short sections, with most ending in a question to answer before moving on to the next section. Working through the case study will improve participants’ knowledge and problem-solving skills in type 2 diabetes by applying evidence-based decisions in the context of individual circumstances. Crucially, participants are invited to respond to the questions by typing in their answers. In this way there is active involvement in the learning process, which is a much more effective way to learn. By actively engaging with this case history, you will feel more confident and empowered to manage such a scenario effectively in the future.

Click here to access the case study

Editorial: updated guidance on prescribing incretin-based therapy, cardiovascular risk reduction and the wider uptake of cgm, how to diagnose and treat hypertension in adults with type 2 diabetes, diabetes distilled: statin heart benefits outweigh diabetes risks, interactive case study: non-diabetic hyperglycaemia – prediabetes, diabetes distilled: smoking cessation cuts excess mortality rates after as little as 3 years, impact of freestyle libre 2 on diabetes distress and glycaemic control in people on twice-daily pre-mixed insulin, updated guidance from the pcds and abcd: managing the national glp-1 ra shortage.

Jane Diggle highlights advice on preventing eye damage when initiating new incretin-based therapies.

Diagnosing and treating hypertension in accordance with updated NICE guidelines.

24 Apr 2024

Quantifying the risk of worsening glycaemia, and how should healthcare professionals respond?

22 Apr 2024

Diagnosing and managing non-diabetic hyperglycaemia.

17 Apr 2024

Sign up to all DiabetesontheNet journals

- CPD Learning

- Journal of Diabetes Nursing

- Diabetes Care for Children & Young People

- The Diabetic Foot Journal

- Diabetes Digest

Useful information

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Editorial policies and ethics

By clicking ‘Subscribe’, you are agreeing that DiabetesontheNet.com are able to email you periodic newsletters. You may unsubscribe from these at any time. Your info is safe with us and we will never sell or trade your details. For information please review our Privacy Policy .

Are you a healthcare professional? This website is for healthcare professionals only. To continue, please confirm that you are a healthcare professional below.

We use cookies responsibly to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue without changing your browser settings, we’ll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies on this website. Read about how we use cookies .

- Open access

- Published: 29 May 2024

A retrospective analysis of the incidence and risk factors of perioperative urinary tract infections after total hysterectomy

- Xianghua Cao 1 na1 ,

- Yunyun Tu 2 na1 ,

- Xinyao Zheng 3 ,

- Guizhen Xu 1 ,

- Qiting Wen 1 ,

- Pengfei Li 1 ,

- Chuan Chen 4 ,

- Qinfeng Yang 5 ,

- Jian Wang 5 ,

- Xueping Li 1 &

- Fang Yu 6

BMC Women's Health volume 24 , Article number: 311 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

21 Accesses

Metrics details

Introduction

Perioperative urinary tract infections (PUTIs) are common in the United States and are a significant contributor to high healthcare costs. There is a lack of large studies on the risk factors for PUTIs after total hysterectomy (TH).

We conducted a retrospective study using a national inpatient sample (NIS) of 445,380 patients from 2010 to 2019 to analyze the risk factors and annual incidence of PUTIs associated with TH perioperatively.

PUTIs were found in 9087 patients overall, showing a 2.0% incidence. There were substantial differences in the incidence of PUTIs based on age group ( P < 0.001). Between the two groups, there was consistently a significant difference in the type of insurance, hospital location, hospital bed size, and hospital type ( P < 0.001). Patients with PUTIs exhibited a significantly higher number of comorbidities ( P < 0.001). Unsurprisingly, patients with PUTIs had a longer median length of stay (5 days vs. 2 days; P < 0.001) and a higher in-hospital death rate (from 0.1 to 1.1%; P < 0.001). Thus, the overall hospitalization expenditures increased by $27,500 in the median ($60,426 vs. $32,926, P < 0.001) as PUTIs increased medical costs. Elective hospitalizations are less common in patients with PUTIs (66.8% vs. 87.6%; P < 0.001). According to multivariate logistic regression study, the following were risk variables for PUTIs following TH: over 45 years old; number of comorbidities (≥ 1); bed size of hospital (medium, large); teaching hospital; region of hospital(south, west); preoperative comorbidities (alcohol abuse, deficiency anemia, chronic blood loss anemia, congestive heart failure, diabetes, drug abuse, hypertension, hypothyroidism, lymphoma, fluid and electrolyte disorders, metastatic cancer, other neurological disorders, paralysis, peripheral vascular disorders, psychoses, pulmonary circulation disorders, renal failure, solid tumor without metastasis, valvular disease, weight loss); and complications (sepsis, acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, pneumonia, stroke, wound infection, wound rupture, hemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, blood transfusion, postoperative delirium).

Conclusions

The findings suggest that identifying these risk factors can lead to improved preventive strategies and management of PUTIs in TH patients. Counseling should be done prior to surgery to reduce the incidence of PUTIs.

The manuscript adds to current knowledge

In medical practice, the identification of risk factors can lead to improved patient prevention and treatment strategies. We conducted a retrospective study using a national inpatient sample (NIS) of 445,380 patients from 2010 to 2019 to analyze the risk factors and annual incidence of PUTIs associated with TH perioperatively. PUTIs were found in 9087 patients overall, showing a 2.0% incidence. We found that noted increased length of hospital stay, medical cost, number of pre-existing comorbidities, size of the hospital, teaching hospitals, and region to also a play a role in the risk of UTI’s.

Clinical topics

Urogynecology

Peer Review reports

Approximately 600,000 women in the United States undergo total hysterectomy (TH) each year, with about 10% opting for subtotal (cervix-preserving) procedures [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. A majority of TH are conducted to address non-cancerous conditions like leiomyomas, abnormal uterine bleeding, and endometriosis, whereas only around 10% are carried out as cancer treatment [ 3 , 4 ]. In 17–23% of cases [ 2 ], there are intraoperative and postoperative problems such as bleeding, infection, and visceral injury.

In the United States, urinary tract infections (UTIs) are prevalent and a major cause of high healthcare expenses; in 2010, direct costs from UTIs exceeded $5 billion [ 5 , 6 ]. Women experience higher rates of UTIs than men do due to anatomical and physiological variations [ 5 , 7 , 8 ]. It has been suggested that the rate of postoperative UTIs is a good measure of surgical quality [ 9 ]. In 2012, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations required all Medicare providers to report surgical site infection rates, including UTIs, in a public registry [ 10 ]. There is a lack of published research on identified risk factors that could be utilized to calculate the incidence of perioperative urinary tract infections (PUTIs) after TH [ 10 , 11 ].

This study’s goals were to find out what percentage of women have PUTIs after TH surgery and associated risk factors.

Materials and methods

Data source.

The national inpatient sample (NIS) database, the largest all-payer database of inpatient admissions in the US, served as the study’s data source. It is a component of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Annually, the NIS obtains a stratified sample of 20% of hospital stays from over 1000 US hospitals [ 12 , 13 ]. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th and 10th editions’ major surgical codes are used to identify patients whose primary procedure is a TH (ICD-9 and ICD-10). Information up until the end of 2015 is coded using ICD-9, while information beyond that through the end of 2016 is coded using ICD-10, in accordance with US coding standards. The data that are currently available include demographics, diagnosis and insurance information, hospital details, length of stay (LOS), total charges, and status of discharge (Table 1 ). Data that has been de-identified is released to the public. Therefore, this study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board.

Study population

Individuals that underwent TH procedures as indicated by ICD-9 codes (68.41/68.49/68.51/68.59/68.61/68.69/68.71/68.79/68.9) and ICD-10 codes (0UT90ZZ/0UT94ZZ/0UT97ZZ/0UT98ZZ/0UT9FZZ/0UB90ZX/0UB90ZZ/0UB93ZX/0UB93ZZ/0UB94ZX/0UB94ZZ/0UB97ZX/0UB97ZZ/0UB98ZX/0UB98ZZ) from 2010 to 2019 ( n = 492,330). Patients with missing data ( n = 46,794) or fewer than 18 years old ( n = 156) were not included in this study. Most of the missing values in this study were based on patient characteristics in the NIS database, and no data were missing for comorbidities and complications, and any missing data were excluded in this study (Fig. 1 ). Ultimately, 445,380 individual patients are included in the analysis. Recruits were split into two groups according to whether or not they had PUTIs.

Flow and inclusion/exclusion of all patients had TH

Outcomes-the postoperative complications

ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes were used to find postoperative complications that could be independently related to PUTIs, such as surgical and medical perioperative issues before discharge. Sepsis, acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, pneumonia, and stroke were all considered perioperative medical problems. Wound infection, wound rupture, bleeding, pulmonary embolism, blood transfusion, and postoperative delirium were among the perioperative medical problems.

Age and race of the patient, hospital features (such as kind of hospital admission, bed capacity, teaching/non-teaching status, location, insurance type, and hospital location), and comorbidities were among the factors. Classification of non-elective/elective admissions, which can potentially separate emergency from elective care. Elective hospitalization refers to planned admissions for medical procedures or treatments that are scheduled in advance and are not considered urgent or emergent. Non-elective hospitalization, also known as emergency or unplanned hospitalization, involves admissions for acute medical conditions or urgent healthcare needs that require immediate attention [ 14 , 15 ]. The Charlson Comorbidity Score was used to find 29 comorbidities that existed before surgery. These were then put into groups using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes (Table 1 ).

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 was used for all data analysis. The demographic and baseline attributes of the subjects were presented as means and standard deviation, or, when applicable, as median and interquartile range for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical data. The Chi-square test was used for nominal and ordinal data, and the Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables. The study used multivariate logistic regression to survey the national inpatient sample (NIS) database of women and find these risk factors (patient demographics, hospital features, preoperative comorbidities, and surgical and medical perioperative problems). The odds ratios (ORs) of baseline parameters and any surgical and medical problems compared between the two groups were computed using binary logistic regression. P < 0.001 was utilized to establish the statistical significance of the alpha level because previous NIS research had used high sample numbers [ 16 ]. Images were drawn using Free Statistics software version 1.9. and pptx. of Word Processing System (WPS) Office (Kingsoft) tools.

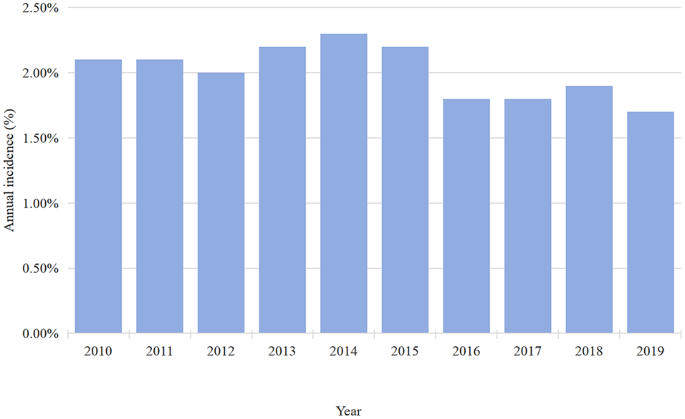

Incidence of PUTIs in patients undergoing TH

Between 2010 and 2019, data on 455,380 TH cases were available in the NIS database. In total, 9087 patients had PUTIs, indicating a 2.0% incidence (Table 2 ). According to our research, the 2.1% incidence of PUTIs persisted in 2010–2011. According to the study, there was an annual decline in the incidence of PUTIs from 2015 (2.2%) to 2019 (1.7%), but an overall increase in the incidence from 2012 (2.0%) to 2014 (2.3%) (Fig. 2 ).

Annual incidence of PUTIs after TH

Patient demographics and hospital characteristics between the two groups

There was a significant difference in the incidence of PUTIs by age group (Table 2 ), with a larger proportion of people over 65 years old reporting PUTIs than people under 65 years old ( P < 0.001). The kind of insurance, hospital bed size, hospital location, and hospital type continuously differed significantly between the two groups (Table 2 ). However, there were no statistically significant differences in terms of hospital region or race (Table 2 ). As was previously mentioned, patients with PUTIs had a noticeably higher number of comorbidities ( P < 0.001). The fact that PUTIs caused an increase in in-hospital mortality from 0.1 to 1.1% ( P < 0.001) (Table 2 ). Table 2 shows that the median length of stay (LOS) for patients with PUTIs was greater than that of patients without PUTIs (5 days vs. 2 days; P < 0.001). According to Table 2 , there was a $27,500 increase in the median hospitalization expenditures for PUTIs ($60,426 vs. $32,926, P < 0.001). Furthermore, Table 2 shows that patients with PUTIs have a decreased likelihood of elective hospital admissions (66.8% vs. 87.6%; P < 0.001).

Risk factors between PUTIs and patient demographics

The following indicators were found by using multivariate logistic regression analysis to investigate risk factors associated with PUTIs (Fig. 3 , Table S1 ): advanced age; number of comorbidity = 1, number of comorbidity = 2, number of comorbidity ≥ 3; medium bed size of hospital, large bed size of hospital; teaching hospital; south of hospital, west of hospital (Fig. 3 , Table S1 ).

Risk factors associated with PUTIs after TH

Interestingly, three protective factors were found to be associated with PUTIs, elective admission, black population and private insurance (Fig. 3 , Table S1 ).

Risk factors between PUTIs and other preoperative comorbidities

The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis were as follows: alcohol abuse, deficiency anemia, chronic blood loss anemia, congestive heart failure, coagulopathy, diabetes, drug abuse, hypertension, lymphoma, fluid and electrolyte disorders, metastatic cancer, other neurological disorders, paralysis, peripheral vascular disorders, psychoses, pulmonary circulation disorders, renal failure, solid tumor without metastasis, valvular disease weight loss (Fig. 4 , Table S2 ).

Comorbidities associated with PUTIs following TH

Risk factors between PUTIs and other postoperative complications

Medical complications of multivariate logistic regression analysis were as follows: sepsis, acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, pneumonia, stroke (Fig. 5 , Table S3 ); However, in multivariate regression analysis, cardiac arrest seemed to be associated with perioperative urinary tract infection (OR = 0.55, 95%CI = 0.35–0.88, P = 0.013), but it was not statistically significant(Fig. 5 , Table S3 ).

Complications associated with PUTIs following TH

Surgical complications of multivariate logistic regression analysis were as follows: wound infection, wound rupture, hemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, blood transfusion, postoperative delirium (Fig. 5 , Table S3 ).

We found the overall occurrence of PUTIs after TH to be 2% (1.7 − 2.3%) between 2010 and 2019 using the NIS database. We identified the following risk factors were associated with the occurrence of PUTIs: age, number of pre-existing comorbidities, size of the hospital, teaching hospitals, and complications. An extensive health economics analysis of PUTIs following TH is provided in the present study. As far as the authors know, this is the first investigation into the prevalence and possible risk factors of PUTIs following a TH. The findings suggest that identifying these risk factors can lead to improved preventive strategies and management of PUTIs in TH patients.

The study found that 2.0% of patients had PUTIs following a TH. Previous research has shown that the incidence of UTIs was less than 5% when the majority of included individuals underwent laparoscopic or abdominal TH [ 5 , 10 , 17 , 18 ]. The incidence of PUTIs stayed at 2.1% throughout the 2010–2011 period, then typically grew from 2012 (2.0%) to 2014 (2.3%) (Fig. 2 ), and then dropped yearly from 2015 (2.2%) to 2019 (1.7%) (Fig. 2 ). The following reasons may be considered for this small fluctuation in the incidence of PUTIs. An explanation for PUTIs may become more common due to a combination of factors, including adequate knowledge and careful control over antibiotic use in medical procedures [ 8 , 19 , 20 ]. On the other hand, the improvement of medical level, preoperative cystoscopy is routinely performed. Routine cystoscopy will improve the detection rate of injury to the urinary tract [ 2 , 21 , 22 , 23 ].

Our results showed that the higher risk of PUTIs increased with age (Fig. 3 ). The frequency of UTI rises with age, and in women over 65, it is around twice as high as in the general female population [ 24 ]. Medina et al. found that the cause of spinal cord dysfunction, comorbidities, age, residential status (institutionalized or not), history of antibiotic usage, and spinal cord dysfunction all play a role in the etiology of this condition in older women [ 24 ]. Women, elderly, or had comorbidities of cerebrovascular accident or chronic renal failure patients have a higher risk of developing PUTIs, according to research by Lin et al [ 25 ]. A study conducted in 2005 found that there was a statistically significant difference in the incidence of UTI diagnoses between subjects 65 years of age and older and younger subjects (16% vs. 4%, P < 0.05) [ 26 ]. Age is an important factor that affects a patient’s overall health, wound healing, limb mobility, and recovery rate after surgery [ 27 ]. Another reason could be that changes that last for a long time in the vaginal flora and vulvovaginal atrophy make defenses against pathogens weaker [ 28 , 29 ], which makes UTIs more likely in women who have gone through menopause.

A retrospective study conducted by Sako et al. [ 30 ], showed that risk factors for low survival include male sex, older age, low bed capacity, and non-academic hospitals. The above studies were limited to small samples, and the evidence was not convincing, while the sample size of this study is large enough to be convincing. Our results suggest that there are risk factors for PUTIs: bed size of hospital (medium, large); teaching hospital; region of hospital (south, west). Teaching hospitals and large medical centers often serve as primary healthcare providers for a significant population [ 31 ]. They are equipped with advanced diagnostic facilities and specialists, making them more capable of diagnosing and treating UTIs. As a result, UTIs are more frequently detected and managed in these settings. These patients may have a higher likelihood of developing UTIs due to factors such as indwelling catheters, compromised immune systems, or underlying medical conditions. This may be related to different groups and comorbidities, family history and genetic predisposition, regional climatic factors, poor hygiene, and overuse of antibiotics [ 32 , 33 ].

In line with previous studies, our results also showed that the occurrence of PUTIs in the perioperative period of TH increased hospital costs and the length of hospital stay [ 26 , 34 , 35 ]. Pokrzywa et al [ 36 ]. found that an increased rate of 30-d complications in elective general surgery patients with UTIs by the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database from 2011 to 2013. However, this study only looked at the relationship between PUTIs and postoperative complications from 2011 to 2013, while our study looked at the relationship between PUTIs and postoperative complications from 2010 to 2019, and conducted an economic analysis. In 25 hospitals across China, Zhu et al [ 37 ]. looked into the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for UTI in immobile patients. They discovered that the following factors were independent risk factors for UTI: older age, female sex, diabetes mellitus, longer hospital stays, being in a medical ward, the presence of an indwelling urethral catheter, prolonged catheter use, glucocorticoid use, and the presence of an indwelling catheter. However, this study only surveyed the population of immobile hospitalized patients.

Our findings also showed that the black population was a protective factor for PUTIs. The main considerations may be genetic variation, lifestyle habits, and past medical history, and environmental economic factors [ 38 ]. Some studies [ 39 , 40 ] have suggested that genetic factors could contribute to the lower incidence of UTIs in certain racial groups, including black populations. It found variations in genes related to immune system function that could influence susceptibility to UTIs. Some research [ 41 , 42 ] has indicated that black individuals in certain regions may have low economic level, less use of antibiotics or may engage in behaviors that reduce UTI risk, although this varies widely depending on location and socioeconomic status. It’s important to note that while these associations exist, they are not absolute or universally applicable. UTIs can affect individuals of all races and socioeconomic backgrounds. Factors such as personal hygiene practices, sexual activity, underlying health conditions, and antibiotic use also significantly influence UTI risk.

Our results showed that a number of comorbidities (≥ 1) was associated with UTIs (Fig. 3 ). Diabetes mellitus is linked to a higher risk of UTIs due to multiple factors, including chronic hyperglycemia, compromised leukocyte function, recurrent UTIs, and abnormalities in the anatomy and function of the urinary tract [ 18 , 43 ]. Lin et al. [ 25 ] revealed that the incidence of high UTIs was substantially correlated with hypertension (HTN), diabetes, coronary heart disease, hyperlipidemia, chronic renal failure, cerebrovascular accidents, and depression. Bausch et al. [ 19 ] discovered that in a risk factor study of UTIs in 665 patients, worse health, higher comorbidities, concomitant immunodeficiency, and end-stage renal failure/hemodialysis were related to an increased risk of postoperative UTIs. This shows that effective interventions are needed to lower the incidence of PUTIs in people who have these traits. It has been demonstrated that active counseling with patients in these comorbidity categories lowers the occurrence of PUTIs [ 26 ]. It is worthwhile to investigate how certain therapies affect the prevalence of PUTIs. Prospective research on the actual prevalence of PUTIs at the time of admission and during hospital stays is also necessary.

Courtney et al. [ 36 ] discovered that the risk of postoperative complications and morbidity can be increased by PUTIs. Complications including congestive heart failure, wound infection, weight loss, and perioperative blood transfusion were more common in the UTIs group [ 36 ]. James et al. [ 44 ] discovered that 30 days after surgery, post-operative infections and negative outcomes were linked to UTIs. UTIs have been linked to higher rates of morbidity and death in patients after colorectal surgery. Additionally, patients who have UTIs are more likely to experience various comorbidities, including sepsis, surgical site infections, and pulmonary embolism [ 45 ]. The studies were retrospective and had small sample sizes, inadequate evidence, and an incomplete analysis of complications. One of the strengths of this study was that we used the NIS database to assess a sizable cohort of women who had TH, and we also included surgical and medical problems in the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Our study has many limitations. One limitation of this study lies in its retrospective methodology, which inherently increases the risk of bias in both measurement and selection. While we enrolled all eligible patients between 2010 and 2019 to mitigate sample bias and reduce the impact of selection bias, it’s important to acknowledge that retrospective analyses can still introduce biases related to data collection, completeness, and accuracy. The second is that our analysis was limited to the variables that existed in the database. For example, the study does not include some need for total resection of uterine disease in the department of gynecology (cervical cancer, uterine benign disease, abnormal uterine bleeding, etc.). This may reduce the external validity of the findings; Previous studies [ 18 ] have reported that the incidence of urinary tract infection in these diseases is not very different. Another potential limitation of retrospective analysis is the underestimation of the incidence of PUTIs due to the absence of preoperative and postoperative follow-up information. There is no way to determine if patients had pre-existing UTI’s prior surgery. The NIS database only includes the patient’s baseline information, preoperative comorbidities, and postoperative complications, but does not include the patient’s uterine size, operation duration, urethral catheter indwelling time, anesthesia-related information, long-term complications, and long-term follow-up data [ 20 ]. Lastly, factors strongly associated in our analysis may be confounded by variables such as malignancy or renal failure, among others. Because these diseases are more prone to PUTIs due to the treatment of immune and immunosuppressive drugs and urinary catheter placement, prospective studies with large samples are needed in the future to reduce the influence of these confounding factors.

Despite these limitations, we believe that this study includes a sufficient sample size to test existing hypotheses, and provides an accurate representation of the incidence of PUTIs from clinical practice in academic centers, and provides some risk factors for PUTIs after TH to aid in preoperative counseling and planning for additional measures to avoid PUTIs in patients who are expected to be at higher risk of PUTIs.

In conclusion, this study aimed to investigate the incidence and risk factors associated with PUTIs following TH using the NIS database. The study identified several risk factors for PUTIs during the perioperative period of TH, including (Fig S1 ): age ≥ 45 years, the number of comorbidities (≥ 1), hospital bed size (medium, large), teaching hospital, hospital region (south, west), preoperative comorbidities (drug abuse, alcohol abuse, hypothyroidism, lymphoma, fluid and electrolyte disorders, metastatic cancer, other neurological disorders, paralysis, peripheral vascular disorders, psychoses, pulmonary circulation disorders, renal failure, solid tumor without metastasis, valvular disease, weight loss), and complications (sepsis, acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, pneumonia, stroke, wound infection, wound rupture, hemorrhage, pulmonary embolism, blood transfusion, postoperative delirium).

The findings suggest that identifying these risk factors can lead to improved preventive strategies and management of PUTIs in TH patients. Future studies may focus on exploring PUTIs following TH in specific patient populations and surgical procedures to enhance tailored interventions.

Data availability

This study is based on data provided by Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The NIS database is a large publicly available full-payer inpatient care database in the United States and the direct web link to the database is https://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/index.html. Therefore, individual or grouped data cannot be shared by the authors.

Abbreviations

Perioperative Urinary tract infections

- Total hysterectomy

Urinary tract infections

Nationwide Inpatient Sample

Length of stay

Pelvic organ prolapse

Hypertension

International Classification of Disease, 9th edition

International Classification of Disease, 10th edition

Odds ratios

Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, Strauss LT, Xia Z, Peterson HB. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:549–55.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vakili B, Chesson RR, Kyle BL, Shobeiri SA, Echols KT, Gist R, et al. The incidence of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy: a prospective analysis based on universal cystoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1599–604.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Simms KT, Yuill S, Killen J, Smith MA, Kulasingam S, De Kok IMCM, et al. Historical and projected hysterectomy rates in the USA: implications for future observed cervical cancer rates and evaluating prevention interventions. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158:710–8.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, Lu Y-S, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of Inpatient Hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:233–41.

El-Nashar SA, Singh R, Schmitt JJ, Leon DC, Arora C, Gebhart JB, et al. Urinary tract infection after hysterectomy for Benign Gynecologic conditions or pelvic reconstructive surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1347–57.

Yang X, Chen H, Zheng Y, Qu S, Wang H, Yi F. Disease burden and long-term trends of urinary tract infections: a worldwide report. Front Public Health. 2022;10:888205.

Czajkowski K, Broś-Konopielko M, Teliga-Czajkowska J. Urinary tract infection in women. Menopausal Rev. 2021;20:40–7.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fernández-García S, Moragas Moreno A, Giner-Soriano M, Morros R, Ouchi D, García-Sangenís A, et al. Urinary tract infections in men in primary care in Catalonia, Spain. Antibiotics. 2023;12:1611.

Enomoto LM, Hollenbeak CS, Bhayani NH, Dillon PW, Gusani NJ. Measuring Surgical Quality: a National Clinical Registry Versus Administrative Claims Data. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1416–22.

Lake AG, McPencow AM, Dick-Biascoechea MA, Martin DK, Erekson EA. Surgical site infection after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:490.e1-490.e9.