Economic bias is especially damaging to girls.

The future of public infrastructure is digital, efficient, and for everyone.

I had a lot of fun filming What’s Next? , which you can watch now.

A few photos from my latest visit to Africa.

With some breakthrough tools, the end of malaria could be here soon.

The tech behind self-driving cars is also helping fight malaria.

We already know how to save millions of newborn lives.

Meet some of the heroes who are fighting poverty and saving lives.

I’m excited to see the latest breakthroughs during my visit this week.

The Lone Star State is showing the world how to power a clean tomorrow.

Kemmerer, Wyoming will soon be home to the most advanced nuclear facility in the world.

And it’s on display this week in London.

Artificial intelligence is as revolutionary as mobile phones and the Internet.

And upend the software industry.

In the sixth episode of my podcast, I sat down with the OpenAI CEO to talk about where AI is headed next and what humanity will do once it gets there.

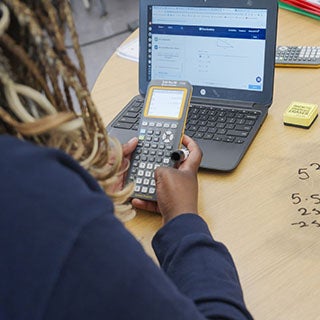

In the second episode of my new podcast, I sat down with the founder of Khan Academy to talk about how artificial intelligence will transform education.

First Avenue Elementary School in Newark is pioneering the use of AI tools in the classroom.

The 2024 Washington State Teacher of the Year believes the answer is yes—and she’s innovating new techniques to support them.

Brave New Words paints an inspiring picture of AI in the classroom.

Infectious Generosity is a timely, inspiring read about philanthropy in the digital age.

The Women gave me a new perspective on the Vietnam War

Kristin Hannah’s wildly popular novel about an army nurse is eye-opening and inspiring.

This is my personal blog, where I share about the people I meet, the books I'm reading, and what I'm learning. I hope that you'll join the conversation.

Q. How do I create a Gates Notes account?

A. there are three ways you can create a gates notes account:.

- Sign up with Facebook. We’ll never post to your Facebook account without your permission.

- Sign up with Twitter. We’ll never post to your Twitter account without your permission.

- Sign up with your email. Enter your email address during sign up. We’ll email you a link for verification.

Q. Will you ever post to my Facebook or Twitter accounts without my permission?

A. no, never., q. how do i sign up to receive email communications from my gates notes account, a. in account settings, click the toggle switch next to “send me updates from bill gates.”, q. how will you use the interests i select in account settings, a. we will use them to choose the suggested reads that appear on your profile page..

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The list of the sleep-deprived heroes includes doctors, nurses, medical cleaners, pathologists, paramedics, ambulance drivers, and health-care administrators. In the fight against …

Thomas Lake writes about real heroes on the frontlines of the coronavirus: the doctors and nurses who put their lives at risk daily.

Read the stories of the courageous workers risking their own lives to save ours during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accounted for tens of thousands of deaths and ultimately will affect millions more people who will survive. There will be time to mourn the victims and care for the survivors. But it is also time to …

At the heart of the Covid-19 pandemic, volunteers have demonstrated an exceptional display of solidarity across the world. Responding to calls for help from their local …

More than 80% of them are women, and they are also disproportionately workers of color. Learn more about the essential role they are playing in the pandemic and what policymakers and employers ...

COVID-19 might be today’s super-villain, but it does not deter our real-life heroes from doing their job and tirelessly working to find ways to combat the threat and eventually beat …

In this paper, I examine what the heroism rhetoric of the COVID-19 pandemic suggests about the social role of medicine. First, I look at the concept of the hero employed to …

Nurses are heroes of the COVID-19 crisis. May 12 is International Nurses Day, which commemorates the birthday of Florence Nightingale, the first “professional nurse.” The World Health...