REALIZING THE PROMISE:

Leading up to the 75th anniversary of the UN General Assembly, this “Realizing the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all?” publication kicks off the Center for Universal Education’s first playbook in a series to help improve education around the world.

It is intended as an evidence-based tool for ministries of education, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, to adopt and more successfully invest in education technology.

While there is no single education initiative that will achieve the same results everywhere—as school systems differ in learners and educators, as well as in the availability and quality of materials and technologies—an important first step is understanding how technology is used given specific local contexts and needs.

The surveys in this playbook are designed to be adapted to collect this information from educators, learners, and school leaders and guide decisionmakers in expanding the use of technology.

Introduction

While technology has disrupted most sectors of the economy and changed how we communicate, access information, work, and even play, its impact on schools, teaching, and learning has been much more limited. We believe that this limited impact is primarily due to technology being been used to replace analog tools, without much consideration given to playing to technology’s comparative advantages. These comparative advantages, relative to traditional “chalk-and-talk” classroom instruction, include helping to scale up standardized instruction, facilitate differentiated instruction, expand opportunities for practice, and increase student engagement. When schools use technology to enhance the work of educators and to improve the quality and quantity of educational content, learners will thrive.

Further, COVID-19 has laid bare that, in today’s environment where pandemics and the effects of climate change are likely to occur, schools cannot always provide in-person education—making the case for investing in education technology.

Here we argue for a simple yet surprisingly rare approach to education technology that seeks to:

- Understand the needs, infrastructure, and capacity of a school system—the diagnosis;

- Survey the best available evidence on interventions that match those conditions—the evidence; and

- Closely monitor the results of innovations before they are scaled up—the prognosis.

RELATED CONTENT

Podcast: How education technology can improve learning for all students

To make ed tech work, set clear goals, review the evidence, and pilot before you scale

The framework.

Our approach builds on a simple yet intuitive theoretical framework created two decades ago by two of the most prominent education researchers in the United States, David K. Cohen and Deborah Loewenberg Ball. They argue that what matters most to improve learning is the interactions among educators and learners around educational materials. We believe that the failed school-improvement efforts in the U.S. that motivated Cohen and Ball’s framework resemble the ed-tech reforms in much of the developing world to date in the lack of clarity improving the interactions between educators, learners, and the educational material. We build on their framework by adding parents as key agents that mediate the relationships between learners and educators and the material (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The instructional core

Adapted from Cohen and Ball (1999)

As the figure above suggests, ed-tech interventions can affect the instructional core in a myriad of ways. Yet, just because technology can do something, it does not mean it should. School systems in developing countries differ along many dimensions and each system is likely to have different needs for ed-tech interventions, as well as different infrastructure and capacity to enact such interventions.

The diagnosis:

How can school systems assess their needs and preparedness.

A useful first step for any school system to determine whether it should invest in education technology is to diagnose its:

- Specific needs to improve student learning (e.g., raising the average level of achievement, remediating gaps among low performers, and challenging high performers to develop higher-order skills);

- Infrastructure to adopt technology-enabled solutions (e.g., electricity connection, availability of space and outlets, stock of computers, and Internet connectivity at school and at learners’ homes); and

- Capacity to integrate technology in the instructional process (e.g., learners’ and educators’ level of familiarity and comfort with hardware and software, their beliefs about the level of usefulness of technology for learning purposes, and their current uses of such technology).

Before engaging in any new data collection exercise, school systems should take full advantage of existing administrative data that could shed light on these three main questions. This could be in the form of internal evaluations but also international learner assessments, such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and/or the Progress in International Literacy Study (PIRLS), and the Teaching and Learning International Study (TALIS). But if school systems lack information on their preparedness for ed-tech reforms or if they seek to complement existing data with a richer set of indicators, we developed a set of surveys for learners, educators, and school leaders. Download the full report to see how we map out the main aspects covered by these surveys, in hopes of highlighting how they could be used to inform decisions around the adoption of ed-tech interventions.

The evidence:

How can school systems identify promising ed-tech interventions.

There is no single “ed-tech” initiative that will achieve the same results everywhere, simply because school systems differ in learners and educators, as well as in the availability and quality of materials and technologies. Instead, to realize the potential of education technology to accelerate student learning, decisionmakers should focus on four potential uses of technology that play to its comparative advantages and complement the work of educators to accelerate student learning (Figure 2). These comparative advantages include:

- Scaling up quality instruction, such as through prerecorded quality lessons.

- Facilitating differentiated instruction, through, for example, computer-adaptive learning and live one-on-one tutoring.

- Expanding opportunities to practice.

- Increasing learner engagement through videos and games.

Figure 2: Comparative advantages of technology

Here we review the evidence on ed-tech interventions from 37 studies in 20 countries*, organizing them by comparative advantage. It’s important to note that ours is not the only way to classify these interventions (e.g., video tutorials could be considered as a strategy to scale up instruction or increase learner engagement), but we believe it may be useful to highlight the needs that they could address and why technology is well positioned to do so.

When discussing specific studies, we report the magnitude of the effects of interventions using standard deviations (SDs). SDs are a widely used metric in research to express the effect of a program or policy with respect to a business-as-usual condition (e.g., test scores). There are several ways to make sense of them. One is to categorize the magnitude of the effects based on the results of impact evaluations. In developing countries, effects below 0.1 SDs are considered to be small, effects between 0.1 and 0.2 SDs are medium, and those above 0.2 SDs are large (for reviews that estimate the average effect of groups of interventions, called “meta analyses,” see e.g., Conn, 2017; Kremer, Brannen, & Glennerster, 2013; McEwan, 2014; Snilstveit et al., 2015; Evans & Yuan, 2020.)

*In surveying the evidence, we began by compiling studies from prior general and ed-tech specific evidence reviews that some of us have written and from ed-tech reviews conducted by others. Then, we tracked the studies cited by the ones we had previously read and reviewed those, as well. In identifying studies for inclusion, we focused on experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations of education technology interventions from pre-school to secondary school in low- and middle-income countries that were released between 2000 and 2020. We only included interventions that sought to improve student learning directly (i.e., students’ interaction with the material), as opposed to interventions that have impacted achievement indirectly, by reducing teacher absence or increasing parental engagement. This process yielded 37 studies in 20 countries (see the full list of studies in Appendix B).

Scaling up standardized instruction

One of the ways in which technology may improve the quality of education is through its capacity to deliver standardized quality content at scale. This feature of technology may be particularly useful in three types of settings: (a) those in “hard-to-staff” schools (i.e., schools that struggle to recruit educators with the requisite training and experience—typically, in rural and/or remote areas) (see, e.g., Urquiola & Vegas, 2005); (b) those in which many educators are frequently absent from school (e.g., Chaudhury, Hammer, Kremer, Muralidharan, & Rogers, 2006; Muralidharan, Das, Holla, & Mohpal, 2017); and/or (c) those in which educators have low levels of pedagogical and subject matter expertise (e.g., Bietenbeck, Piopiunik, & Wiederhold, 2018; Bold et al., 2017; Metzler & Woessmann, 2012; Santibañez, 2006) and do not have opportunities to observe and receive feedback (e.g., Bruns, Costa, & Cunha, 2018; Cilliers, Fleisch, Prinsloo, & Taylor, 2018). Technology could address this problem by: (a) disseminating lessons delivered by qualified educators to a large number of learners (e.g., through prerecorded or live lessons); (b) enabling distance education (e.g., for learners in remote areas and/or during periods of school closures); and (c) distributing hardware preloaded with educational materials.

Prerecorded lessons

Technology seems to be well placed to amplify the impact of effective educators by disseminating their lessons. Evidence on the impact of prerecorded lessons is encouraging, but not conclusive. Some initiatives that have used short instructional videos to complement regular instruction, in conjunction with other learning materials, have raised student learning on independent assessments. For example, Beg et al. (2020) evaluated an initiative in Punjab, Pakistan in which grade 8 classrooms received an intervention that included short videos to substitute live instruction, quizzes for learners to practice the material from every lesson, tablets for educators to learn the material and follow the lesson, and LED screens to project the videos onto a classroom screen. After six months, the intervention improved the performance of learners on independent tests of math and science by 0.19 and 0.24 SDs, respectively but had no discernible effect on the math and science section of Punjab’s high-stakes exams.

One study suggests that approaches that are far less technologically sophisticated can also improve learning outcomes—especially, if the business-as-usual instruction is of low quality. For example, Naslund-Hadley, Parker, and Hernandez-Agramonte (2014) evaluated a preschool math program in Cordillera, Paraguay that used audio segments and written materials four days per week for an hour per day during the school day. After five months, the intervention improved math scores by 0.16 SDs, narrowing gaps between low- and high-achieving learners, and between those with and without educators with formal training in early childhood education.

Yet, the integration of prerecorded material into regular instruction has not always been successful. For example, de Barros (2020) evaluated an intervention that combined instructional videos for math and science with infrastructure upgrades (e.g., two “smart” classrooms, two TVs, and two tablets), printed workbooks for students, and in-service training for educators of learners in grades 9 and 10 in Haryana, India (all materials were mapped onto the official curriculum). After 11 months, the intervention negatively impacted math achievement (by 0.08 SDs) and had no effect on science (with respect to business as usual classes). It reduced the share of lesson time that educators devoted to instruction and negatively impacted an index of instructional quality. Likewise, Seo (2017) evaluated several combinations of infrastructure (solar lights and TVs) and prerecorded videos (in English and/or bilingual) for grade 11 students in northern Tanzania and found that none of the variants improved student learning, even when the videos were used. The study reports effects from the infrastructure component across variants, but as others have noted (Muralidharan, Romero, & Wüthrich, 2019), this approach to estimating impact is problematic.

A very similar intervention delivered after school hours, however, had sizeable effects on learners’ basic skills. Chiplunkar, Dhar, and Nagesh (2020) evaluated an initiative in Chennai (the capital city of the state of Tamil Nadu, India) delivered by the same organization as above that combined short videos that explained key concepts in math and science with worksheets, facilitator-led instruction, small groups for peer-to-peer learning, and occasional career counseling and guidance for grade 9 students. These lessons took place after school for one hour, five times a week. After 10 months, it had large effects on learners’ achievement as measured by tests of basic skills in math and reading, but no effect on a standardized high-stakes test in grade 10 or socio-emotional skills (e.g., teamwork, decisionmaking, and communication).

Drawing general lessons from this body of research is challenging for at least two reasons. First, all of the studies above have evaluated the impact of prerecorded lessons combined with several other components (e.g., hardware, print materials, or other activities). Therefore, it is possible that the effects found are due to these additional components, rather than to the recordings themselves, or to the interaction between the two (see Muralidharan, 2017 for a discussion of the challenges of interpreting “bundled” interventions). Second, while these studies evaluate some type of prerecorded lessons, none examines the content of such lessons. Thus, it seems entirely plausible that the direction and magnitude of the effects depends largely on the quality of the recordings (e.g., the expertise of the educator recording it, the amount of preparation that went into planning the recording, and its alignment with best teaching practices).

These studies also raise three important questions worth exploring in future research. One of them is why none of the interventions discussed above had effects on high-stakes exams, even if their materials are typically mapped onto the official curriculum. It is possible that the official curricula are simply too challenging for learners in these settings, who are several grade levels behind expectations and who often need to reinforce basic skills (see Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). Another question is whether these interventions have long-term effects on teaching practices. It seems plausible that, if these interventions are deployed in contexts with low teaching quality, educators may learn something from watching the videos or listening to the recordings with learners. Yet another question is whether these interventions make it easier for schools to deliver instruction to learners whose native language is other than the official medium of instruction.

Distance education

Technology can also allow learners living in remote areas to access education. The evidence on these initiatives is encouraging. For example, Johnston and Ksoll (2017) evaluated a program that broadcasted live instruction via satellite to rural primary school students in the Volta and Greater Accra regions of Ghana. For this purpose, the program also equipped classrooms with the technology needed to connect to a studio in Accra, including solar panels, a satellite modem, a projector, a webcam, microphones, and a computer with interactive software. After two years, the intervention improved the numeracy scores of students in grades 2 through 4, and some foundational literacy tasks, but it had no effect on attendance or classroom time devoted to instruction, as captured by school visits. The authors interpreted these results as suggesting that the gains in achievement may be due to improving the quality of instruction that children received (as opposed to increased instructional time). Naik, Chitre, Bhalla, and Rajan (2019) evaluated a similar program in the Indian state of Karnataka and also found positive effects on learning outcomes, but it is not clear whether those effects are due to the program or due to differences in the groups of students they compared to estimate the impact of the initiative.

In one context (Mexico), this type of distance education had positive long-term effects. Navarro-Sola (2019) took advantage of the staggered rollout of the telesecundarias (i.e., middle schools with lessons broadcasted through satellite TV) in 1968 to estimate its impact. The policy had short-term effects on students’ enrollment in school: For every telesecundaria per 50 children, 10 students enrolled in middle school and two pursued further education. It also had a long-term influence on the educational and employment trajectory of its graduates. Each additional year of education induced by the policy increased average income by nearly 18 percent. This effect was attributable to more graduates entering the labor force and shifting from agriculture and the informal sector. Similarly, Fabregas (2019) leveraged a later expansion of this policy in 1993 and found that each additional telesecundaria per 1,000 adolescents led to an average increase of 0.2 years of education, and a decline in fertility for women, but no conclusive evidence of long-term effects on labor market outcomes.

It is crucial to interpret these results keeping in mind the settings where the interventions were implemented. As we mention above, part of the reason why they have proven effective is that the “counterfactual” conditions for learning (i.e., what would have happened to learners in the absence of such programs) was either to not have access to schooling or to be exposed to low-quality instruction. School systems interested in taking up similar interventions should assess the extent to which their learners (or parts of their learner population) find themselves in similar conditions to the subjects of the studies above. This illustrates the importance of assessing the needs of a system before reviewing the evidence.

Preloaded hardware

Technology also seems well positioned to disseminate educational materials. Specifically, hardware (e.g., desktop computers, laptops, or tablets) could also help deliver educational software (e.g., word processing, reference texts, and/or games). In theory, these materials could not only undergo a quality assurance review (e.g., by curriculum specialists and educators), but also draw on the interactions with learners for adjustments (e.g., identifying areas needing reinforcement) and enable interactions between learners and educators.

In practice, however, most initiatives that have provided learners with free computers, laptops, and netbooks do not leverage any of the opportunities mentioned above. Instead, they install a standard set of educational materials and hope that learners find them helpful enough to take them up on their own. Students rarely do so, and instead use the laptops for recreational purposes—often, to the detriment of their learning (see, e.g., Malamud & Pop-Eleches, 2011). In fact, free netbook initiatives have not only consistently failed to improve academic achievement in math or language (e.g., Cristia et al., 2017), but they have had no impact on learners’ general computer skills (e.g., Beuermann et al., 2015). Some of these initiatives have had small impacts on cognitive skills, but the mechanisms through which those effects occurred remains unclear.

To our knowledge, the only successful deployment of a free laptop initiative was one in which a team of researchers equipped the computers with remedial software. Mo et al. (2013) evaluated a version of the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) program for grade 3 students in migrant schools in Beijing, China in which the laptops were loaded with a remedial software mapped onto the national curriculum for math (similar to the software products that we discuss under “practice exercises” below). After nine months, the program improved math achievement by 0.17 SDs and computer skills by 0.33 SDs. If a school system decides to invest in free laptops, this study suggests that the quality of the software on the laptops is crucial.

To date, however, the evidence suggests that children do not learn more from interacting with laptops than they do from textbooks. For example, Bando, Gallego, Gertler, and Romero (2016) compared the effect of free laptop and textbook provision in 271 elementary schools in disadvantaged areas of Honduras. After seven months, students in grades 3 and 6 who had received the laptops performed on par with those who had received the textbooks in math and language. Further, even if textbooks essentially become obsolete at the end of each school year, whereas laptops can be reloaded with new materials for each year, the costs of laptop provision (not just the hardware, but also the technical assistance, Internet, and training associated with it) are not yet low enough to make them a more cost-effective way of delivering content to learners.

Evidence on the provision of tablets equipped with software is encouraging but limited. For example, de Hoop et al. (2020) evaluated a composite intervention for first grade students in Zambia’s Eastern Province that combined infrastructure (electricity via solar power), hardware (projectors and tablets), and educational materials (lesson plans for educators and interactive lessons for learners, both loaded onto the tablets and mapped onto the official Zambian curriculum). After 14 months, the intervention had improved student early-grade reading by 0.4 SDs, oral vocabulary scores by 0.25 SDs, and early-grade math by 0.22 SDs. It also improved students’ achievement by 0.16 on a locally developed assessment. The multifaceted nature of the program, however, makes it challenging to identify the components that are driving the positive effects. Pitchford (2015) evaluated an intervention that provided tablets equipped with educational “apps,” to be used for 30 minutes per day for two months to develop early math skills among students in grades 1 through 3 in Lilongwe, Malawi. The evaluation found positive impacts in math achievement, but the main study limitation is that it was conducted in a single school.

Facilitating differentiated instruction

Another way in which technology may improve educational outcomes is by facilitating the delivery of differentiated or individualized instruction. Most developing countries massively expanded access to schooling in recent decades by building new schools and making education more affordable, both by defraying direct costs, as well as compensating for opportunity costs (Duflo, 2001; World Bank, 2018). These initiatives have not only rapidly increased the number of learners enrolled in school, but have also increased the variability in learner’ preparation for schooling. Consequently, a large number of learners perform well below grade-based curricular expectations (see, e.g., Duflo, Dupas, & Kremer, 2011; Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). These learners are unlikely to get much from “one-size-fits-all” instruction, in which a single educator delivers instruction deemed appropriate for the middle (or top) of the achievement distribution (Banerjee & Duflo, 2011). Technology could potentially help these learners by providing them with: (a) instruction and opportunities for practice that adjust to the level and pace of preparation of each individual (known as “computer-adaptive learning” (CAL)); or (b) live, one-on-one tutoring.

Computer-adaptive learning

One of the main comparative advantages of technology is its ability to diagnose students’ initial learning levels and assign students to instruction and exercises of appropriate difficulty. No individual educator—no matter how talented—can be expected to provide individualized instruction to all learners in his/her class simultaneously . In this respect, technology is uniquely positioned to complement traditional teaching. This use of technology could help learners master basic skills and help them get more out of schooling.

Although many software products evaluated in recent years have been categorized as CAL, many rely on a relatively coarse level of differentiation at an initial stage (e.g., a diagnostic test) without further differentiation. We discuss these initiatives under the category of “increasing opportunities for practice” below. CAL initiatives complement an initial diagnostic with dynamic adaptation (i.e., at each response or set of responses from learners) to adjust both the initial level of difficulty and rate at which it increases or decreases, depending on whether learners’ responses are correct or incorrect.

Existing evidence on this specific type of programs is highly promising. Most famously, Banerjee et al. (2007) evaluated CAL software in Vadodara, in the Indian state of Gujarat, in which grade 4 students were offered two hours of shared computer time per week before and after school, during which they played games that involved solving math problems. The level of difficulty of such problems adjusted based on students’ answers. This program improved math achievement by 0.35 and 0.47 SDs after one and two years of implementation, respectively. Consistent with the promise of personalized learning, the software improved achievement for all students. In fact, one year after the end of the program, students assigned to the program still performed 0.1 SDs better than those assigned to a business as usual condition. More recently, Muralidharan, et al. (2019) evaluated a “blended learning” initiative in which students in grades 4 through 9 in Delhi, India received 45 minutes of interaction with CAL software for math and language, and 45 minutes of small group instruction before or after going to school. After only 4.5 months, the program improved achievement by 0.37 SDs in math and 0.23 SDs in Hindi. While all learners benefited from the program in absolute terms, the lowest performing learners benefited the most in relative terms, since they were learning very little in school.

We see two important limitations from this body of research. First, to our knowledge, none of these initiatives has been evaluated when implemented during the school day. Therefore, it is not possible to distinguish the effect of the adaptive software from that of additional instructional time. Second, given that most of these programs were facilitated by local instructors, attempts to distinguish the effect of the software from that of the instructors has been mostly based on noncausal evidence. A frontier challenge in this body of research is to understand whether CAL software can increase the effectiveness of school-based instruction by substituting part of the regularly scheduled time for math and language instruction.

Live one-on-one tutoring

Recent improvements in the speed and quality of videoconferencing, as well as in the connectivity of remote areas, have enabled yet another way in which technology can help personalization: live (i.e., real-time) one-on-one tutoring. While the evidence on in-person tutoring is scarce in developing countries, existing studies suggest that this approach works best when it is used to personalize instruction (see, e.g., Banerjee et al., 2007; Banerji, Berry, & Shotland, 2015; Cabezas, Cuesta, & Gallego, 2011).

There are almost no studies on the impact of online tutoring—possibly, due to the lack of hardware and Internet connectivity in low- and middle-income countries. One exception is Chemin and Oledan (2020)’s recent evaluation of an online tutoring program for grade 6 students in Kianyaga, Kenya to learn English from volunteers from a Canadian university via Skype ( videoconferencing software) for one hour per week after school. After 10 months, program beneficiaries performed 0.22 SDs better in a test of oral comprehension, improved their comfort using technology for learning, and became more willing to engage in cross-cultural communication. Importantly, while the tutoring sessions used the official English textbooks and sought in part to help learners with their homework, tutors were trained on several strategies to teach to each learner’s individual level of preparation, focusing on basic skills if necessary. To our knowledge, similar initiatives within a country have not yet been rigorously evaluated.

Expanding opportunities for practice

A third way in which technology may improve the quality of education is by providing learners with additional opportunities for practice. In many developing countries, lesson time is primarily devoted to lectures, in which the educator explains the topic and the learners passively copy explanations from the blackboard. This setup leaves little time for in-class practice. Consequently, learners who did not understand the explanation of the material during lecture struggle when they have to solve homework assignments on their own. Technology could potentially address this problem by allowing learners to review topics at their own pace.

Practice exercises

Technology can help learners get more out of traditional instruction by providing them with opportunities to implement what they learn in class. This approach could, in theory, allow some learners to anchor their understanding of the material through trial and error (i.e., by realizing what they may not have understood correctly during lecture and by getting better acquainted with special cases not covered in-depth in class).

Existing evidence on practice exercises reflects both the promise and the limitations of this use of technology in developing countries. For example, Lai et al. (2013) evaluated a program in Shaanxi, China where students in grades 3 and 5 were required to attend two 40-minute remedial sessions per week in which they first watched videos that reviewed the material that had been introduced in their math lessons that week and then played games to practice the skills introduced in the video. After four months, the intervention improved math achievement by 0.12 SDs. Many other evaluations of comparable interventions have found similar small-to-moderate results (see, e.g., Lai, Luo, Zhang, Huang, & Rozelle, 2015; Lai et al., 2012; Mo et al., 2015; Pitchford, 2015). These effects, however, have been consistently smaller than those of initiatives that adjust the difficulty of the material based on students’ performance (e.g., Banerjee et al., 2007; Muralidharan, et al., 2019). We hypothesize that these programs do little for learners who perform several grade levels behind curricular expectations, and who would benefit more from a review of foundational concepts from earlier grades.

We see two important limitations from this research. First, most initiatives that have been evaluated thus far combine instructional videos with practice exercises, so it is hard to know whether their effects are driven by the former or the latter. In fact, the program in China described above allowed learners to ask their peers whenever they did not understand a difficult concept, so it potentially also captured the effect of peer-to-peer collaboration. To our knowledge, no studies have addressed this gap in the evidence.

Second, most of these programs are implemented before or after school, so we cannot distinguish the effect of additional instructional time from that of the actual opportunity for practice. The importance of this question was first highlighted by Linden (2008), who compared two delivery mechanisms for game-based remedial math software for students in grades 2 and 3 in a network of schools run by a nonprofit organization in Gujarat, India: one in which students interacted with the software during the school day and another one in which students interacted with the software before or after school (in both cases, for three hours per day). After a year, the first version of the program had negatively impacted students’ math achievement by 0.57 SDs and the second one had a null effect. This study suggested that computer-assisted learning is a poor substitute for regular instruction when it is of high quality, as was the case in this well-functioning private network of schools.

In recent years, several studies have sought to remedy this shortcoming. Mo et al. (2014) were among the first to evaluate practice exercises delivered during the school day. They evaluated an initiative in Shaanxi, China in which students in grades 3 and 5 were required to interact with the software similar to the one in Lai et al. (2013) for two 40-minute sessions per week. The main limitation of this study, however, is that the program was delivered during regularly scheduled computer lessons, so it could not determine the impact of substituting regular math instruction. Similarly, Mo et al. (2020) evaluated a self-paced and a teacher-directed version of a similar program for English for grade 5 students in Qinghai, China. Yet, the key shortcoming of this study is that the teacher-directed version added several components that may also influence achievement, such as increased opportunities for teachers to provide students with personalized assistance when they struggled with the material. Ma, Fairlie, Loyalka, and Rozelle (2020) compared the effectiveness of additional time-delivered remedial instruction for students in grades 4 to 6 in Shaanxi, China through either computer-assisted software or using workbooks. This study indicates whether additional instructional time is more effective when using technology, but it does not address the question of whether school systems may improve the productivity of instructional time during the school day by substituting educator-led with computer-assisted instruction.

Increasing learner engagement

Another way in which technology may improve education is by increasing learners’ engagement with the material. In many school systems, regular “chalk and talk” instruction prioritizes time for educators’ exposition over opportunities for learners to ask clarifying questions and/or contribute to class discussions. This, combined with the fact that many developing-country classrooms include a very large number of learners (see, e.g., Angrist & Lavy, 1999; Duflo, Dupas, & Kremer, 2015), may partially explain why the majority of those students are several grade levels behind curricular expectations (e.g., Muralidharan, et al., 2019; Muralidharan & Zieleniak, 2014; Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). Technology could potentially address these challenges by: (a) using video tutorials for self-paced learning and (b) presenting exercises as games and/or gamifying practice.

Video tutorials

Technology can potentially increase learner effort and understanding of the material by finding new and more engaging ways to deliver it. Video tutorials designed for self-paced learning—as opposed to videos for whole class instruction, which we discuss under the category of “prerecorded lessons” above—can increase learner effort in multiple ways, including: allowing learners to focus on topics with which they need more help, letting them correct errors and misconceptions on their own, and making the material appealing through visual aids. They can increase understanding by breaking the material into smaller units and tackling common misconceptions.

In spite of the popularity of instructional videos, there is relatively little evidence on their effectiveness. Yet, two recent evaluations of different versions of the Khan Academy portal, which mainly relies on instructional videos, offer some insight into their impact. First, Ferman, Finamor, and Lima (2019) evaluated an initiative in 157 public primary and middle schools in five cities in Brazil in which the teachers of students in grades 5 and 9 were taken to the computer lab to learn math from the platform for 50 minutes per week. The authors found that, while the intervention slightly improved learners’ attitudes toward math, these changes did not translate into better performance in this subject. The authors hypothesized that this could be due to the reduction of teacher-led math instruction.

More recently, Büchel, Jakob, Kühnhanss, Steffen, and Brunetti (2020) evaluated an after-school, offline delivery of the Khan Academy portal in grades 3 through 6 in 302 primary schools in Morazán, El Salvador. Students in this study received 90 minutes per week of additional math instruction (effectively nearly doubling total math instruction per week) through teacher-led regular lessons, teacher-assisted Khan Academy lessons, or similar lessons assisted by technical supervisors with no content expertise. (Importantly, the first group provided differentiated instruction, which is not the norm in Salvadorian schools). All three groups outperformed both schools without any additional lessons and classrooms without additional lessons in the same schools as the program. The teacher-assisted Khan Academy lessons performed 0.24 SDs better, the supervisor-led lessons 0.22 SDs better, and the teacher-led regular lessons 0.15 SDs better, but the authors could not determine whether the effects across versions were different.

Together, these studies suggest that instructional videos work best when provided as a complement to, rather than as a substitute for, regular instruction. Yet, the main limitation of these studies is the multifaceted nature of the Khan Academy portal, which also includes other components found to positively improve learner achievement, such as differentiated instruction by students’ learning levels. While the software does not provide the type of personalization discussed above, learners are asked to take a placement test and, based on their score, educators assign them different work. Therefore, it is not clear from these studies whether the effects from Khan Academy are driven by its instructional videos or to the software’s ability to provide differentiated activities when combined with placement tests.

Games and gamification

Technology can also increase learner engagement by presenting exercises as games and/or by encouraging learner to play and compete with others (e.g., using leaderboards and rewards)—an approach known as “gamification.” Both approaches can increase learner motivation and effort by presenting learners with entertaining opportunities for practice and by leveraging peers as commitment devices.

There are very few studies on the effects of games and gamification in low- and middle-income countries. Recently, Araya, Arias Ortiz, Bottan, and Cristia (2019) evaluated an initiative in which grade 4 students in Santiago, Chile were required to participate in two 90-minute sessions per week during the school day with instructional math software featuring individual and group competitions (e.g., tracking each learner’s standing in his/her class and tournaments between sections). After nine months, the program led to improvements of 0.27 SDs in the national student assessment in math (it had no spillover effects on reading). However, it had mixed effects on non-academic outcomes. Specifically, the program increased learners’ willingness to use computers to learn math, but, at the same time, increased their anxiety toward math and negatively impacted learners’ willingness to collaborate with peers. Finally, given that one of the weekly sessions replaced regular math instruction and the other one represented additional math instructional time, it is not clear whether the academic effects of the program are driven by the software or the additional time devoted to learning math.

The prognosis:

How can school systems adopt interventions that match their needs.

Here are five specific and sequential guidelines for decisionmakers to realize the potential of education technology to accelerate student learning.

1. Take stock of how your current schools, educators, and learners are engaging with technology .

Carry out a short in-school survey to understand the current practices and potential barriers to adoption of technology (we have included suggested survey instruments in the Appendices); use this information in your decisionmaking process. For example, we learned from conversations with current and former ministers of education from various developing regions that a common limitation to technology use is regulations that hold school leaders accountable for damages to or losses of devices. Another common barrier is lack of access to electricity and Internet, or even the availability of sufficient outlets for charging devices in classrooms. Understanding basic infrastructure and regulatory limitations to the use of education technology is a first necessary step. But addressing these limitations will not guarantee that introducing or expanding technology use will accelerate learning. The next steps are thus necessary.

“In Africa, the biggest limit is connectivity. Fiber is expensive, and we don’t have it everywhere. The continent is creating a digital divide between cities, where there is fiber, and the rural areas. The [Ghanaian] administration put in schools offline/online technologies with books, assessment tools, and open source materials. In deploying this, we are finding that again, teachers are unfamiliar with it. And existing policies prohibit students to bring their own tablets or cell phones. The easiest way to do it would have been to let everyone bring their own device. But policies are against it.” H.E. Matthew Prempeh, Minister of Education of Ghana, on the need to understand the local context.

2. Consider how the introduction of technology may affect the interactions among learners, educators, and content .

Our review of the evidence indicates that technology may accelerate student learning when it is used to scale up access to quality content, facilitate differentiated instruction, increase opportunities for practice, or when it increases learner engagement. For example, will adding electronic whiteboards to classrooms facilitate access to more quality content or differentiated instruction? Or will these expensive boards be used in the same way as the old chalkboards? Will providing one device (laptop or tablet) to each learner facilitate access to more and better content, or offer students more opportunities to practice and learn? Solely introducing technology in classrooms without additional changes is unlikely to lead to improved learning and may be quite costly. If you cannot clearly identify how the interactions among the three key components of the instructional core (educators, learners, and content) may change after the introduction of technology, then it is probably not a good idea to make the investment. See Appendix A for guidance on the types of questions to ask.

3. Once decisionmakers have a clear idea of how education technology can help accelerate student learning in a specific context, it is important to define clear objectives and goals and establish ways to regularly assess progress and make course corrections in a timely manner .

For instance, is the education technology expected to ensure that learners in early grades excel in foundational skills—basic literacy and numeracy—by age 10? If so, will the technology provide quality reading and math materials, ample opportunities to practice, and engaging materials such as videos or games? Will educators be empowered to use these materials in new ways? And how will progress be measured and adjusted?

4. How this kind of reform is approached can matter immensely for its success.

It is easy to nod to issues of “implementation,” but that needs to be more than rhetorical. Keep in mind that good use of education technology requires thinking about how it will affect learners, educators, and parents. After all, giving learners digital devices will make no difference if they get broken, are stolen, or go unused. Classroom technologies only matter if educators feel comfortable putting them to work. Since good technology is generally about complementing or amplifying what educators and learners already do, it is almost always a mistake to mandate programs from on high. It is vital that technology be adopted with the input of educators and families and with attention to how it will be used. If technology goes unused or if educators use it ineffectually, the results will disappoint—no matter the virtuosity of the technology. Indeed, unused education technology can be an unnecessary expenditure for cash-strapped education systems. This is why surveying context, listening to voices in the field, examining how technology is used, and planning for course correction is essential.

5. It is essential to communicate with a range of stakeholders, including educators, school leaders, parents, and learners .

Technology can feel alien in schools, confuse parents and (especially) older educators, or become an alluring distraction. Good communication can help address all of these risks. Taking care to listen to educators and families can help ensure that programs are informed by their needs and concerns. At the same time, deliberately and consistently explaining what technology is and is not supposed to do, how it can be most effectively used, and the ways in which it can make it more likely that programs work as intended. For instance, if teachers fear that technology is intended to reduce the need for educators, they will tend to be hostile; if they believe that it is intended to assist them in their work, they will be more receptive. Absent effective communication, it is easy for programs to “fail” not because of the technology but because of how it was used. In short, past experience in rolling out education programs indicates that it is as important to have a strong intervention design as it is to have a solid plan to socialize it among stakeholders.

Beyond reopening: A leapfrog moment to transform education?

On September 14, the Center for Universal Education (CUE) will host a webinar to discuss strategies, including around the effective use of education technology, for ensuring resilient schools in the long term and to launch a new education technology playbook “Realizing the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all?”

file-pdf Full Playbook – Realizing the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all? file-pdf References file-pdf Appendix A – Instruments to assess availability and use of technology file-pdf Appendix B – List of reviewed studies file-pdf Appendix C – How may technology affect interactions among students, teachers, and content?

About the Authors

Alejandro j. ganimian, emiliana vegas, frederick m. hess.

- Media Relations

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Self-Regulated Learning: What It Is, Why It Is Important and Strategies for Implementing It

Self-regulated learning (SRL) is a respected educational approach which encourages students to take control of their own unique learning journey. In this approach, students are guided through the process of effectively planning , monitoring , and reflecting on their work. There are a number of key advantages of this approach, including improved academic performance , better time management , and higher levels of motivation . The concept of SRL gained prominence in the 1980s and draws on various theoretical perspectives, such as constructivism , cognitive theory, and Vygotsky’s theory of the Zone of Proximal Development . This article aims to introduce teachers to the approach and offers practical advice on facilitating self-regulated learning in the classroom (2).

What is Self-Regulated Learning?

Self-regulated learning is partly about self-control but, more significantly, it is also about having an active and personal involvement in your own education. Instead of passively following instructions, students are encouraged to use special thinking and motivational strategies to improve their ability to learn. Furthermore, they can also have agency to improve their own learning environments to match their unique needs (1).

The fact that SRL can be personalised is one of its key benefits, allowing students to decide on the type of instruction that suits them best. By being proactive in this way, students take responsibility for their own learning. This approach, therefore, is useful not just in academic settings but also in daily skills like time management and goal setting. Overall, self-regulated learning empowers students to be more effective learners and active participants in their own educational journey (3).

See also: Adaptive Learning: What is It, What are its Benefits and How Does it Work?

Strategies to teach self-regulation

Teaching self-regulation to students is not just about telling them what to do. Instead, teachers can incorporate teaching of specific practical methods into their lessons. This section offers strategies for teachers to help students become more proactive and successful in their learning.

Active Thinking about Learning Strategies

Teachers can help students think more actively about effective learning strategies. When planning a syllabus, allocate time before an assessment to guide students to consider the type of questions they will face, the resources they will need, and how to use those resources. This helps students plan effectively and make good use of study materials. For example, before a science exam, the teacher could guide students on which topics to focus on and how to use resources effectively for revision. This helps students plan their study time better.

Model Goal-Oriented Behaviour

Show students how to set goals and break them down into smaller tasks with deadlines. For instance, if students are required to watch a video asynchronously, set a viewing deadline followed by a small quiz. This helps students better plan and monitor their own learning habits. Ideally, this should be done earlier in the course in order to encourage good habits later.

Incorporate Frequent Discourse on Self-Regulation

Talk to your students about the SRL approach. Make self-regulation a regular topic in the classroom. This can start from conducting a survey before the first class in order to find out about students’ previous learning approaches. Subsequently, early in the course, teachers can describe self-regulated learning skills and their benefits, before referring back to this in later lessons.

Planning Classwork

Encourage students to spread their work over time instead of cramming it all in at once. Use tools like digital timesheets to help students monitor their study habits. This kind of reflection can help them become more aware of how much and how well they are learning.

Explicit Strategy Discussion

Label and discuss strategies openly during classroom activities. For instance, during a class discussion, encourage students to share the strategies they used to understand the material. As an example, after students have read a difficult scientific article for homework, you could ask them how they managed to understand the key points. Some might say they drew diagrams to visualise the concept, while others might have made flashcards for memorisation. Highlighting these different approaches not only validates each student’s method but also exposes the class to a variety of strategies they may not have used before. This becomes a learning opportunity for everyone, improving their toolkit for understanding difficult texts in the future (4).

Feedback and Reflection

Provide constructive feedback on how students are doing in relation to course goals. Encourage them to think about which learning strategies worked or did not work for them. If a dedicated digital space can be created for reflection, this might help students structure how they engage with self-evaluation. Also, while it takes a bit of extra work, providing a rubric for assignments to help students understand what is expected can help them plan and evaluate their own work accordingly.

Using caution and best judgement

By bringing in these techniques, teachers can help students become more aware of their learning processes and adapt their strategies for more effective learning. The idea is that these methods equip students with the self-regulatory skills useful not just in academic tasks but also in daily life. However, when promoting self-regulated learning strategies, teachers must be careful not to overwhelm students with too many methods all at once. Instead, introduce strategies gradually to allow time for understanding. Also, avoid a one-size-fits-all approach, as each student’s learning style is unique. When possible, teachers should think critically about whether the strategies are actually helping students or instead causing additional stress (5). Lastly, it is vital to give students room to make mistakes and learn from them, rather than strictly dictating how they should manage their learning. Ideally, students need to feel a strong sense of agency in their learning progress.

See also: How Can We Align Learning Objectives, Instructional Strategies, and Assessments?

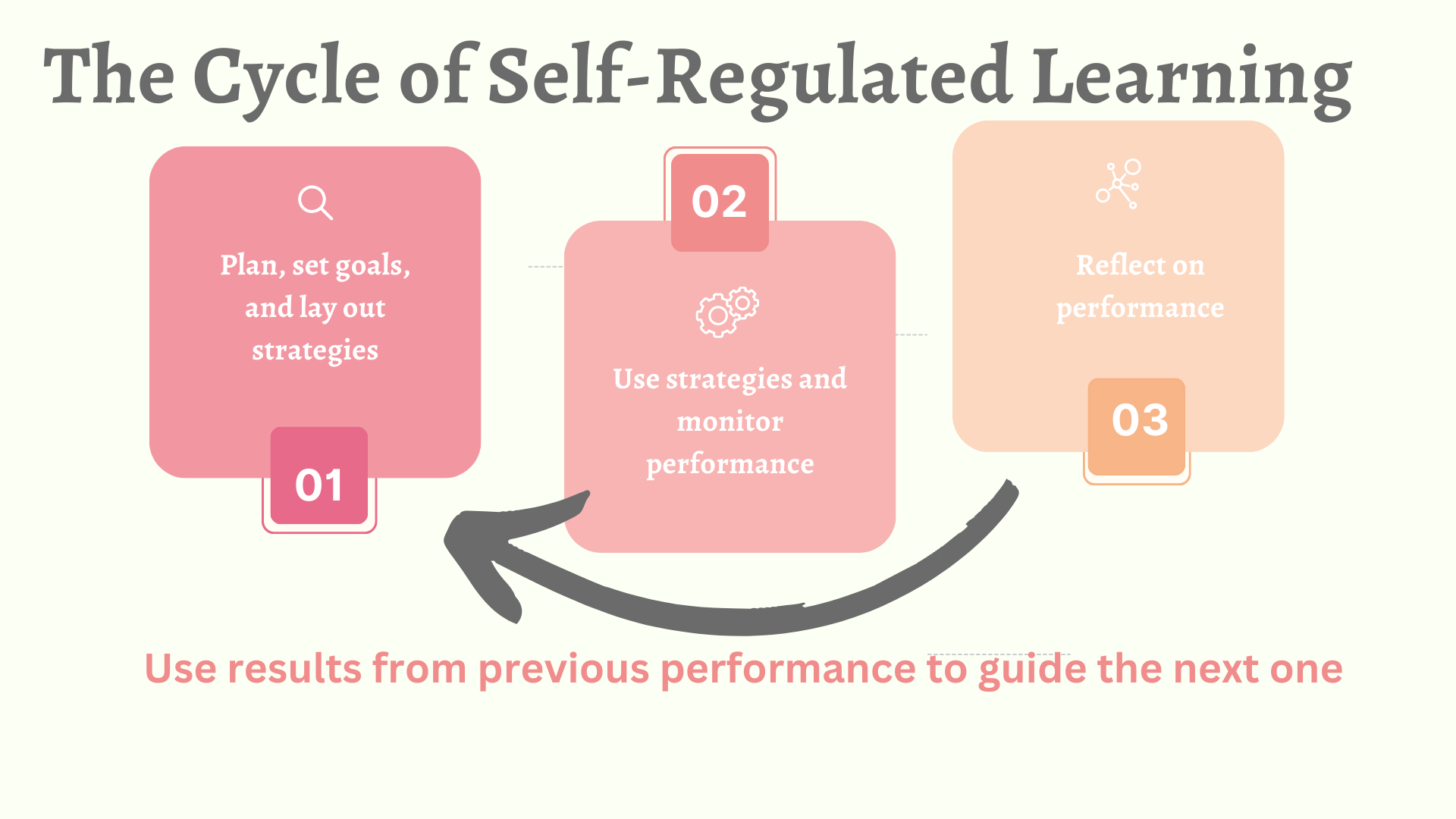

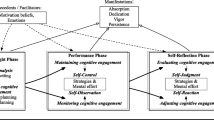

The Cycle of Self-Regulated Learning

The self-regulated learning cycle (illustrated in the diagram below) is a framework that emphasises the role of the student in their own learning process. While students are the main actors, teachers, as previously mentioned, also play a very important role as guides and coaches. This approach aligns well with established educational theories like constructivism, which emphasises the learner’s role in building their own knowledge.

1. Plan, Set Goals, and Lay Out Strategies

Before getting started with a task, students should be encouraged to spend time planning. Not all students will be enthusiastic and for some it might feel like a step backward. However, in reality this can help students make more efficient use of their time and effort. As a simple example, if students are assigned a research paper, the planning phase could include a decision to spend the first week on researching and the second week on writing, or students could be asked to create a mind-map based on the essay question.

What can teachers do to help students through this phase?

In the planning phase, teachers should encourage students to evaluate the characteristics of the task, asking them to consider if it is similar to tasks they have previously completed and how much time it might require. Next, teachers can prompt students to set clear goals, and to consider if they think the research can be completed by the end of the week. To achieve these goals, students should be encouraged to outline specific strategies, asking them if they will need to visit the library or consult online resources. Finally, students can be taught to set realistic expectations by questioning what outcomes they are aiming for, taking into account past performance and the effort they are willing to put in (6).

Here, the teacher’s role is akin to that of a ‘ scaffolder ‘ in Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. Teachers should aim to provide the right amount of support to help students reach their potential.

See also: Situated Learning Theory

2. Monitor Performance through the use of targeted strategies

Once the planning is complete, students move into the execution phase. This is where they put their plan into action, and it is important for students to monitor their performance to see if their plan is working. For example, if a student finds that reading a textbook in a noisy dorm room is not working for them, a change of location to a quieter library might be needed.

In the phase where students are putting their plan into action, teachers can still play a significant role. They can encourage students to engage in self-observation by asking them to identify strategies that are effective and those that are not. Teachers can also guide students to prepare for potential obstacles, encouraging them to think in advance about possible challenges and ways to overcome them. Lastly, students can be motivated to remain committed to new strategies, even when they feel uncomfortable or unfamiliar at the outset. This monitoring phase is similar to the strategies of metacognitive theory, encouraging awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes (7).

3. Reflect on Performance

As all teachers will be aware, reflection is crucial. Rather than just focusing on grades, students should assess how well they did in relation to their initial goals. If, in the past, a student aimed for a ‘B’ but ended up with a ‘C’, they should consider what went wrong and how to improve.

In the reflection phase, teachers should help students gain insights into their performance. For example, teachers can guide students to evaluate their own efforts and the effectiveness of their chosen strategies. A good idea here is to set up some kind of learning journal with space for students to reflect on specific tasks at specific times. In these journals, students can be encouraged to consider whether the strategies they used brought about the hoped-for results. Moreover, teachers can instruct students to connect any poor outcomes to unsuccessful strategies or insufficient effort, rather than allow students to blame it on an inherent lack of ability. Reflection is a vital component of experiential learning theories, such as Kolb’s Learning Cycle , where experiences lead to observations and reflections, which can then progress into future planning and actions (8).

By integrating the above steps into your teaching practice, you can help students to take control of their learning, which can then set them up for success both academically and in other aspects of life.

See also: Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

Why is self-regulation important?

As has been described in this article, self-regulated learning can facilitate both effective learning and personal growth. It can empower students to improve their academic performance by promoting self-reflection. Through this self-assessment and resource management, it is hoped that students can develop a more refined understanding of how to tackle learning tasks and improve their study techniques. To be clear, we are not simply talking about better grades. This approach can also positively influence a student’s mental well-being, allowing them to feel more in control of their performance and experience less stress, especially during exams.

The significance of SRL can become even more pronounced at the college level. University courses often present greater challenges and have less educator oversight compared to high school. Unfortunately, many students start higher education without the necessary learning skills, which can result in some of them feeling outclassed by their peers. Implementing SRL earlier in their academic journeys can level the playing field for these students, helping them become more confident and self-reliant.

Moreover, the current trend of remote learning also shows the importance of SRL. The virtual classroom setting requires even more planning and self-direction due to the fact that online courses are often less structured. In these challenging times, when students are often dealing with stress, having strong self-regulation skills can give them a sense of self-efficacy, and, as mentioned earlier, this positive mindset is not just helpful for the current academic setting but continues to be beneficial long after graduation.

See also: Kirkpatrick Model: Four Levels of Learning Evaluation

In summary, self-regulated learning is more than just a modern education concept. On some levels, it can be described as a set of life skills that has been valued, perhaps informally, throughout history for its positive impact on behaviour and skill acquisition. Furthermore, this approach is deeply embedded in cognitive learning theory, emphasising the active role of students in shaping their own educational outcomes. By employing a set of coherent learning strategies, students can positively affect their own cognition, motivation, and behaviour.

Importantly, teachers serve as the all-important facilitators in this process, not only passing on academic strategies but also empowering students with self-regulation techniques that improve their overall learning. Whether this is in a traditional classroom or a remote setting, these skills can help students become more responsible and effective learners. In an ever-changing educational landscape, the role of self-regulated learning is increasingly central, helping students become well-rounded, resilient individuals, better prepared to navigate the challenges of academic life and beyond.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64-70.

- Burman, Jeremy T.; Green, Christopher D.; Shanker, Stuart (September 2015). “On the Meanings of Self-Regulation: Digital Humanities in Service of Conceptual Clarity” (PDF). Child Development. 86 (5): 1507–1521. doi:10.1111/cdev.12395.

- Butler, Deborah L.; Winne, Philip H. (1995). “Feedback and Self-Regulated Learning: A Theoretical Synthesis”. Review of Educational Research. American Educational Research Association (AERA). 65 (3): 245–281. doi:10.3102/00346543065003245. ISSN 0034-6543.

- Winne, Philip H.; Perry, Nancy E. (2000). “Measuring Self-Regulated Learning”. Handbook of Self-Regulation. Elsevier. pp. 531–566. doi:10.1016/b978-012109890-2/50045-7.

- Zimmerman, Barry J (1989). “A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning”. Journal of Educational Psychology. 81 (3): 329–339. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329.

- Williams, Peter E.; Hellman, Chan M. (1 February 2004). “Differences in Self-Regulation for Online Learning Between First- and Second-Generation College Students”. Research in Higher Education. 45 (1): 71–82. doi:10.1023/B:RIHE.0000010047.46814.78.

- Jansen, R. S., Van Leeuwen, A., Janssen, J., Jak, S., & Kester, L. (2019). Self-regulated learning partially mediates the effect of self-regulated learning interventions on achievement in higher education: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 28, 100292.

- Carter Jr, R. A., Rice, M., Yang, S., & Jackson, H. A. (2020). Self-regulated learning in online learning environments: strategies for remote learning. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(5/6), 321-329.

I am a professor of Educational Technology. I have worked at several elite universities. I hold a PhD degree from the University of Illinois and a master's degree from Purdue University.

Similar Posts

Addie model: instructional design.

For many years now, educators and instructional designers alike have used the ADDIE Instructional Design (ID) method as a framework in designing and developing educational and training programs. “ADDIE” stands for Analyze, Design,…

TPACK: Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge Framework

What is TPACK? Technology has become an increasingly important part of students’ lives beyond school, and even within the classroom it can also help increase their understanding of complex concepts or encourage collaboration…

ASSURE: Instructional Design Model

ASSURE is an instructional design model that has the goal of producing more effective teaching and learning. “ASSURE” is an acronym that stands for the various steps in the model. The following is…

Jean Piaget and His Theory & Stages of Cognitive Development

One of the most popular theories of cognitive development was created by Jean Piaget, a Swiss psychologist who believed that cognitive growth occurred in stages. Piaget studied children through to their teens in…

Connectivism Learning Theory

In the field of education, three predominant learning theories have long been at the forefront of theorists’ minds. These are behaviourism, cognitivism, and constructivism. Countless research frameworks have been tied to these three…

Theory of Moral Development – Piaget

There are three stages in Piaget’s Theory of Moral Development. In stage one, children are not concerned with moral reasoning as they prioritize other skills such as social development and dexterity. In stage…

Topic 7: Educational Technology

Technology and self reliance.

Technology is the application of science to address the problems of daily life, from hunting tools and agricultural advances, to manual and electronic ways of computing, to today’s tablets and smartphones. (Photo (a) courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; Photo (b) courtesy of Martin Pettitt/flickr; Photo (c) courtesy of Whitefield d./flickr; Photo (d) courtesy of Andrew Parnell/flickr; Photo (e) courtesy of Jemimus/flickr; Photo (f) courtesy of Kārlis Dambrāns/flickr)

It is easy to look at the latest sleek Apple product and think technology is a recent addition to our world. But from the steam engine to the most cutting-edge robotic surgery tools, technology has described the application of science to address the problems of daily life. We might look back at the enormous and clunky computers of the 1970s that had about as much storage as an iPod Shuffle and roll our eyes in disbelief. But chances are thirty years from now our skinny laptops and iPods will look just as archaic.

What Is Technology?

While most people probably picture computers and cell phones when the subject of technology comes up, technology is not merely a product of the modern era. For example, fire and stone tools were important forms that technology developed during the Stone Age. Just as the availability of digital technology shapes how we live today, the creation of stone tools changed how premodern humans lived and how well they ate. From the first calculator, invented in 2400 B.C.E. Babylon in the form of an abacus, to the predecessor of the modern computer, created in 1882 by Charles Babbage, all of our technological innovations are advancements on previous iterations. And indeed, all aspects of our lives today are influenced by technology. In agriculture, the introduction of machines that can till, thresh, plant, and harvest greatly reduced the need for manual labor, which in turn meant there were fewer rural jobs. This led to the urbanization of society, as well as lowered birthrates because there was less need for large families to work the farms. In the criminal justice system, the ability to ascertain innocence through DNA testing has saved the lives of people on death row. The examples are endless: technology plays a role in absolutely every aspect of our lives.

Technological Inequality

Some schools sport cutting-edge computer labs, while others sport barbed wire. Is your academic technology at the cusp of innovation, relatively disadvantaged, or somewhere in between? (Photo courtesy of Carlos Martinez/flickr)

As with any improvement to human society, not everyone has equal access. Technology, in particular, often creates changes that lead to ever greater inequalities. In short, the gap gets wider faster. This technological stratification has led to a new focus on ensuring better access for all.

There are two forms of technological stratification. The first is differential class-based access to technology in the form of the digital divide. This digital divide has led to the second form, a knowledge gap , which is, as it sounds, an ongoing and increasing gap in information for those who have less access to technology. Simply put, students in well-funded schools receive more exposure to technology than students in poorly funded schools. Those students with more exposure gain more proficiency, which makes them far more marketable in an increasingly technology-based job market and leaves our society divided into those with technological knowledge and those without. Even as we improve access, we have failed to address an increasingly evident gap in e-readiness —the ability to sort through, interpret, and process knowledge (Sciadas 2003).

Since the beginning of the millennium, social science researchers have tried to bring attention to the digital divide , the uneven access to technology among different races, classes, and geographic areas. The term became part of the common lexicon in 1996, when then Vice President Al Gore used it in a speech. This was the point when personal computer use shifted dramatically, from 300,000 users in 1991 to more than 10 million users by 1996 (Rappaport 2009). In part, the issue of the digital divide had to do with communities that received infrastructure upgrades that enabled high-speed Internet access, upgrades that largely went to affluent urban and suburban areas, leaving out large swaths of the country.

At the end of the twentieth century, technology access was also a big part of the school experience for those whose communities could afford it. Early in the millennium, poorer communities had little or no technology access, while well-off families had personal computers at home and wired classrooms in their schools. In the 2000s, however, the prices for low-end computers dropped considerably, and it appeared the digital divide was naturally ending. Research demonstrates that technology use and Internet access still vary a great deal by race, class, and age in the United States, though most studies agree that there is minimal difference in Internet use by adult men and adult women.

Data from the Pew Research Center (2011) suggests the emergence of yet another divide. As technological devices gets smaller and more mobile, larger percentages of minority groups (such as Latinos and African Americans) are using their phones to connect to the Internet. In fact, about 50 percent of people in these minority groups connect to the web via such devices, whereas only one-third of whites do (Washington 2011). And while it might seem that the Internet is the Internet, regardless of how you get there, there’s a notable difference. Tasks like updating a résumé or filling out a job application are much harder on a cell phone than on a wired computer in the home. As a result, the digital divide might mean no access to computers or the Internet, but could mean access to the kind of online technology that allows for empowerment, not just entertainment (Washington 2011).

Mossberger, Tolbert, and Gilbert (2006) demonstrated that the majority of the digital divide for African Americans could be explained by demographic and community-level characteristics, such as socioeconomic status and geographic location. For the Latino population, ethnicity alone, regardless of economics or geography, seemed to limit technology use. Liff and Shepard (2004) found that women, who are accessing technology shaped primarily by male users, feel less confident in their Internet skills and have less Internet access at both work and home. Finally, Guillen and Suarez (2005) found that the global digital divide resulted from both the economic and sociopolitical characteristics of countries.

Use of Technology and Social Media in Society by Individuals

Do you own an e-reader or tablet? What about your parents or your friends? How often do you check social media or your cell phone? Does all this technology have a positive or negative impact on your life? When it comes to cell phones, 67 percent of users check their phones for messages or calls even when the phone wasn’t ringing. In addition, “44% of cell owners have slept with their phone next to their bed because they wanted to make sure they didn’t miss any calls, text messages, or other updates during the night and 29% of cell owners describe their cell phone as ‘something they can’t imagine living without’” (Smith 2012).

While people report that cell phones make it easier to stay in touch, simplify planning and scheduling their daily activities, and increase their productivity, that’s not the only impact of increased cell phone ownership in the United States. Smith also reports that “roughly one in five cell owners say that their phone has made it at least somewhat harder to forget about work at home or on the weekends; to give people their undivided attention; or to focus on a single task without being distracted” (Smith 2012).

A new survey from the Pew Research Center reported that 73 percent of adults engage in some sort of social networking online. Facebook was the most popular platform, and both Facebook users and Instagram users check their sites on a daily basis. Over a third of users check their sites more than once a day (Duggan and Smith 2013).

With so many people using social media both in the United States and abroad, it is no surprise that social media is a powerful force for social change. You will read more about the fight for democracy in the Middle East embodied in the Arab Spring in Chapters 17 and 21, but spreading democracy is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to using social media to incite change. For example, McKenna Pope, a thirteen-year-old girl, used the Internet to successfully petition Hasbro to fight gender stereotypes by creating a gender-neutral Easy-Bake Oven instead of using only the traditional pink color (Kumar 2014). Meanwhile in Latvia, two twenty-three-year-olds used a U.S. State Department grant to create an e-petition platform so citizens could submit ideas directly to the Latvian government. If at least 20 percent of the Latvian population (roughly 407,200 people) supports a petition, the government will look at it (Kumar 2014).

Online Privacy and Security

As we increase our footprints on the web by going online more often to connect socially, share material, conduct business, and store information, we also increase our vulnerability to those with criminal intent. The Pew Research Center recently published a report that indicated the number of Internet users who express concern over the extent of personal information about them available online jumped 17 percent between 2009 and 2013. In that same survey, 12 percent of respondents indicated they had been harassed online, and 11 percent indicated that personal information, such as their Social Security number, had been stolen (Rainie, Kiesler, Kang, and Madden 2013).

Online privacy and security is a key organizational concern as well. Recent large-scale data breaches at retailers such as Target, financial powerhouses such as JP Morgan, the government health insurance site Healthcare.gov, and cell phone providers such as Verizon, exposed millions of people to the threat of identity theft when hackers got access to personal information by compromising website security.

For example, in late August 2014, hackers breached the iCloud data storage site and promptly leaked wave after wave of nude photos from the private accounts of actors such as Jennifer Lawrence and Kirsten Dunst (Lewis 2014). While large-scale data breaches that affect corporations and celebrities are more likely to make the news, individuals may put their personal information at risk simply by clicking a suspect link in an official sounding e-mail.

How can individuals protect their data? Numerous facts sheets available through the government, nonprofits, and the private sector outline common safety measures, including the following: become familiar with privacy rights; read privacy policies when making a purchase (rather than simply clicking “accept”); give out only the minimum information requested by any source; ask why information is being collected, how it is going to be used, and who will have access it; and monitor your credit history for red flags that indicate your identity has been compromised.

Net Neutrality

The issue of net neutrality, the principle that all Internet data should be treated equally by Internet service providers, is part of the national debate about Internet access and the digital divide. On one side of this debate is the belief that those who provide Internet service, like those who provide electricity and water, should be treated as common carriers, legally prohibited from discriminating based on the customer or nature of the goods. Supporters of net neutrality suggest that without such legal protections, the Internet could be divided into “fast” and “slow” lanes. A conflict perspective theorist might suggest that this discrimination would allow bigger corporations, such as Amazon, to pay Internet providers a premium for faster service, which could lead to gaining an advantage that would drive small, local competitors out of business.

The other side of the debate holds the belief that designating Internet service providers as common carriers would constitute an unreasonable regulatory burden and limit the ability of telecommunication companies to operate profitably. A functional perspective theorist might point out that, without profits, companies would not invest in making improvements to their Internet service or expanding those services to underserved areas. The final decision rests with the Federal Communications Commission and the federal government, which must decide how to fairly regulate broadband providers without dividing the Internet into haves and have-nots.

Technology is the application of science to address the problems of daily life. The fast pace of technological advancement means the advancements are continuous, but that not everyone has equal access. The gap created by this unequal access has been termed the digital divide. The knowledge gap refers to an effect of the digital divide: the lack of knowledge or information that keeps those who were not exposed to technology from gaining marketable skills.