Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS & VIEWS FORUM

- 10 February 2020

Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health

- Jonathan Haidt &

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

The topic in brief

• There is an ongoing debate about whether social media and the use of digital devices are detrimental to mental health.

• Adolescents tend to be heavy users of these devices, and especially of social media.

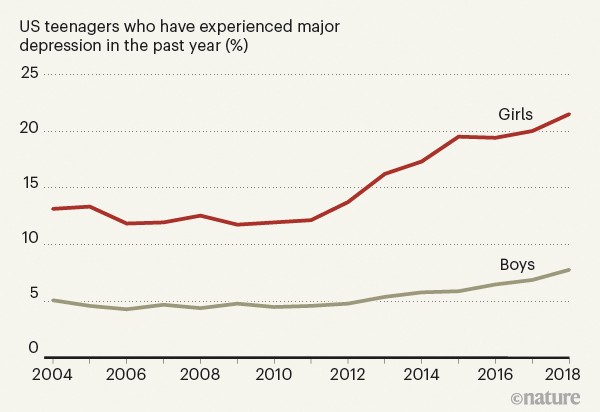

• Rates of teenage depression began to rise around 2012, when adolescent use of social media became common (Fig. 1).

• Some evidence indicates that frequent users of social media have higher rates of depression and anxiety than do light users.

• But perhaps digital devices could provide a way of gathering data about mental health in a systematic way, and make interventions more timely.

Figure 1 | Depression on the rise. Rates of depression among teenagers in the United States have increased steadily since 2012. Rates are higher and are increasing more rapidly for girls than for boys. Some researchers think that social media is the cause of this increase, whereas others see social media as a way of tackling it. (Data taken from the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Table 11.2b; go.nature.com/3ayjaww )

JONATHAN HAIDT: A guilty verdict

A sudden increase in the rates of depression, anxiety and self-harm was seen in adolescents — particularly girls — in the United States and the United Kingdom around 2012 or 2013 (see go.nature.com/2up38hw ). Only one suspect was in the right place at the right time to account for this sudden change: social media. Its use by teenagers increased most quickly between 2009 and 2011, by which point two-thirds of 15–17-year-olds were using it on a daily basis 1 . Some researchers defend social media, arguing that there is only circumstantial evidence for its role in mental-health problems 2 , 3 . And, indeed, several studies 2 , 3 show that there is only a small correlation between time spent on screens and bad mental-health outcomes. However, I present three arguments against this defence.

First, the papers that report small or null effects usually focus on ‘screen time’, but it is not films or video chats with friends that damage mental health. When research papers allow us to zoom in on social media, rather than looking at screen time as a whole, the correlations with depression are larger, and they are larger still when we look specifically at girls ( go.nature.com/2u74der ). The sex difference is robust, and there are several likely causes for it. Girls use social media much more than do boys (who, in turn, spend more of their time gaming). And, for girls more than boys, social life and status tend to revolve around intimacy and inclusion versus exclusion 4 , making them more vulnerable to both the ‘fear of missing out’ and the relational aggression that social media facilitates.

Second, although correlational studies can provide only circumstantial evidence, most of the experiments published in recent years have found evidence of causation ( go.nature.com/2u74der ). In these studies, people are randomly assigned to groups that are asked to continue using social media or to reduce their use substantially. After a few weeks, people who reduce their use generally report an improvement in mood or a reduction in loneliness or symptoms of depression.

The best way forward

Third, many researchers seem to be thinking about social media as if it were sugar: safe in small to moderate quantities, and harmful only if teenagers consume large quantities. But, unlike sugar, social media does not act just on those who consume it. It has radically transformed the nature of peer relationships, family relationships and daily activities 5 . When most of the 11-year-olds in a class are on Instagram (as was the case in my son’s school), there can be pervasive effects on everyone. Children who opt out can find themselves isolated. A simple dose–response model cannot capture the full effects of social media, yet nearly all of the debate among researchers so far has been over the size of the dose–response effect. To cite just one suggestive finding of what lies beyond that model: network effects for depression and anxiety are large, and bad mental health spreads more contagiously between women than between men 6 .

In conclusion, digital media in general undoubtedly has many beneficial uses, including the treatment of mental illness. But if you focus on social media, you’ll find stronger evidence of harm, and less exculpatory evidence, especially for its millions of under-age users.

What should we do while researchers hash out the meaning of these conflicting findings? I would urge a focus on middle schools (roughly 11–13-year-olds in the United States), both for researchers and policymakers. Any US state could quickly conduct an informative experiment beginning this September: randomly assign a portion of school districts to ban smartphone access for students in middle school, while strongly encouraging parents to prevent their children from opening social-media accounts until they begin high school (at around 14). Within 2 years, we would know whether the policy reversed the otherwise steady rise of mental-health problems among middle-school students, and whether it also improved classroom dynamics (as rated by teachers) and test scores. Such system-wide and cross-school interventions would be an excellent way to study the emergent effects of social media on the social lives and mental health of today’s adolescents.

NICK ALLEN: Use digital technology to our advantage

It is appealing to condemn social media out of hand on the basis of the — generally rather poor-quality and inconsistent — evidence suggesting that its use is associated with mental-health problems 7 . But focusing only on its potential harmful effects is comparable to proposing that the only question to ask about cars is whether people can die driving them. The harmful effects might be real, but they don’t tell the full story. The task of research should be to understand what patterns of digital-device and social-media use can lead to beneficial versus harmful effects 7 , and to inform evidence-based approaches to policy, education and regulation.

Long-standing problems have hampered our efforts to improve access to, and the quality of, mental-health services and support. Digital technology has the potential to address some of these challenges. For instance, consider the challenges associated with collecting data on human behaviour. Assessment in mental-health care and research relies almost exclusively on self-reporting, but the resulting data are subjective and burdensome to collect. As a result, assessments are conducted so infrequently that they do not provide insights into the temporal dynamics of symptoms, which can be crucial for both diagnosis and treatment planning.

By contrast, mobile phones and other Internet-connected devices provide an opportunity to continuously collect objective information on behaviour in the context of people’s real lives, generating a rich data set that can provide insight into the extent and timing of mental-health needs in individuals 8 , 9 . By building apps that can track our digital exhaust (the data generated by our everyday digital lives, including our social-media use), we can gain insights into aspects of behaviour that are well-established building blocks of mental health and illness, such as mood, social communication, sleep and physical activity.

Stress and the city

These data can, in turn, be used to empower individuals, by giving them actionable insights into patterns of behaviour that might otherwise have remained unseen. For example, subtle shifts in patterns of sleep or social communication can provide early warning signs of deteriorating mental health. Data on these patterns can be used to alert people to the need for self-management before the patterns — and the associated symptoms — become more severe. Individuals can also choose to share these data with health professionals or researchers. For instance, in the Our Data Helps initiative, individuals who have experienced a suicidal crisis, or the relatives of those who have died by suicide, can donate their digital data to research into suicide risk.

Because mobile devices are ever-present in people’s lives, they offer an opportunity to provide interventions that are timely, personalized and scalable. Currently, mental-health services are mainly provided through a century-old model in which they are made available at times chosen by the mental-health practitioner, rather than at the person’s time of greatest need. But Internet-connected devices are facilitating the development of a wave of ‘just-in-time’ interventions 10 for mental-health care and support.

A compelling example of these interventions involves short-term risk for suicide 9 , 11 — for which early detection could save many lives. Most of the effective approaches to suicide prevention work by interrupting suicidal actions and supporting alternative methods of coping at the moment of greatest risk. If these moments can be detected in an individual’s digital exhaust, a wide range of intervention options become available, from providing information about coping skills and social support, to the initiation of crisis responses. So far, just-in-time approaches have been applied mainly to behaviours such as eating or substance abuse 8 . But with the development of an appropriate research base, these approaches have the potential to provide a major advance in our ability to respond to, and prevent, mental-health crises.

These advantages are particularly relevant to teenagers. Because of their extensive use of digital devices, adolescents are especially vulnerable to the devices’ risks and burdens. And, given the increases in mental-health problems in this age group, teens would also benefit most from improvements in mental-health prevention and treatment. If we use the social and data-gathering functions of Internet-connected devices in the right ways, we might achieve breakthroughs in our ability to improve mental health and well-being.

Nature 578 , 226-227 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00296-x

Twenge, J. M., Martin, G. N. & Spitzberg, B. H. Psychol. Pop. Media Culture 8 , 329–345 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Orben, A. & Przybylski, A. K. Nature Hum. Behav. 3 , 173–182 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Odgers, C. L. & Jensen, M. R. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13190 (2020).

Maccoby, E. E. The Two Sexes: Growing Up Apart, Coming Together Ch. 2 (Harvard Univ. Press, 1999).

Google Scholar

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S. & Prinstein, M. J. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 21 , 267–294 (2018).

Rosenquist, J. N., Fowler, J. H. & Christakis, N. A. Molec. Psychiatry 16 , 273–281 (2011).

Orben, A. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4 (2020).

Mohr, D. C., Zhang, M. & Schueller, S. M. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 13 , 23–47 (2017).

Nelson, B. W. & Allen, N. B. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13 , 718–733 (2018).

Nahum-Shani, I. et al. Ann. Behav. Med. 52 , 446–462 (2018).

Allen, N. B., Nelson, B. W., Brent, D. & Auerbach, R. P. J. Affect. Disord. 250 , 163–169 (2019).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Competing Interests

N.A. has an equity interest in Ksana Health, a company he co-founded and which has the sole commercial licence for certain versions of the Effortless Assessment of Risk States (EARS) mobile-phone application and some related EARS tools. This intellectual property was developed as part of his research at the University of Oregon’s Center for Digital Mental Health (CDMH).

Related Articles

See all News & Views

- Human behaviour

How a tree-hugging protest transformed Indian environmentalism

Comment 26 MAR 24

Scientists under arrest: the researchers taking action over climate change

News Feature 21 FEB 24

Gender bias is more exaggerated in online images than in text

News & Views 14 FEB 24

Use fines from EU social-media act to fund research on adolescent mental health

Correspondence 09 APR 24

Circulating myeloid-derived MMP8 in stress susceptibility and depression

Article 07 FEB 24

Only 0.5% of neuroscience studies look at women’s health. Here’s how to change that

World View 21 NOV 23

Daniel Kahneman obituary: psychologist who revolutionized the way we think about thinking

Obituary 03 MAY 24

Pandemic lockdowns were less of a shock for people with fewer ties

Research Highlight 01 MAY 24

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

W3-Professorship (with tenure) in Inorganic Chemistry

The Institute of Inorganic Chemistry in the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences at the University of Bonn invites applications for a W3-Pro...

53113, Zentrum (DE)

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität

Principal Investigator Positions at the Chinese Institutes for Medical Research, Beijing

Studies of mechanisms of human diseases, drug discovery, biomedical engineering, public health and relevant interdisciplinary fields.

Beijing, China

The Chinese Institutes for Medical Research (CIMR), Beijing

Research Associate - Neural Development Disorders

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Staff Scientist - Mitochondria and Surgery

Recruitment of talent positions at shengjing hospital of china medical university.

Call for top experts and scholars in the field of science and technology.

Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- The Internet and the Pandemic

90% of Americans say the internet has been essential or important to them, many made video calls and 40% used technology in new ways. But while tech was a lifeline for some, others faced struggles

Table of contents.

- 1. How the internet and technology shaped Americans’ personal experiences amid COVID-19

- 2. Parents, their children and school during the pandemic

- 3. Navigating technological challenges

- 4. The role of technology in COVID-19 vaccine registration

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

Pew Research Center has a long history of studying technology adoption trends and the impact of digital technology on society. This report focuses on American adults’ experiences with and attitudes about their internet and technology use during the COVID-19 outbreak. For this analysis, we surveyed 4,623 U.S. adults from April 12-18, 2021. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Chapter 1 of this report includes responses to an open-ended question and the overall report includes a number of quotations to help illustrate themes and add nuance to the survey findings. Quotations may have been lightly edited for grammar, spelling and clarity. The first three themes mentioned in each open-ended response, according to a researcher-developed codebook, were coded into categories for analysis.

Here are the questions used for this report , along with responses, and its methodology .

The coronavirus has transformed many aspects of Americans’ lives. It shut down schools, businesses and workplaces and forced millions to stay at home for extended lengths of time. Public health authorities recommended limits on social contact to try to contain the spread of the virus, and these profoundly altered the way many worked, learned, connected with loved ones, carried out basic daily tasks, celebrated and mourned. For some, technology played a role in this transformation.

Results from a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults conducted April 12-18, 2021, reveal the extent to which people’s use of the internet has changed, their views about how helpful technology has been for them and the struggles some have faced.

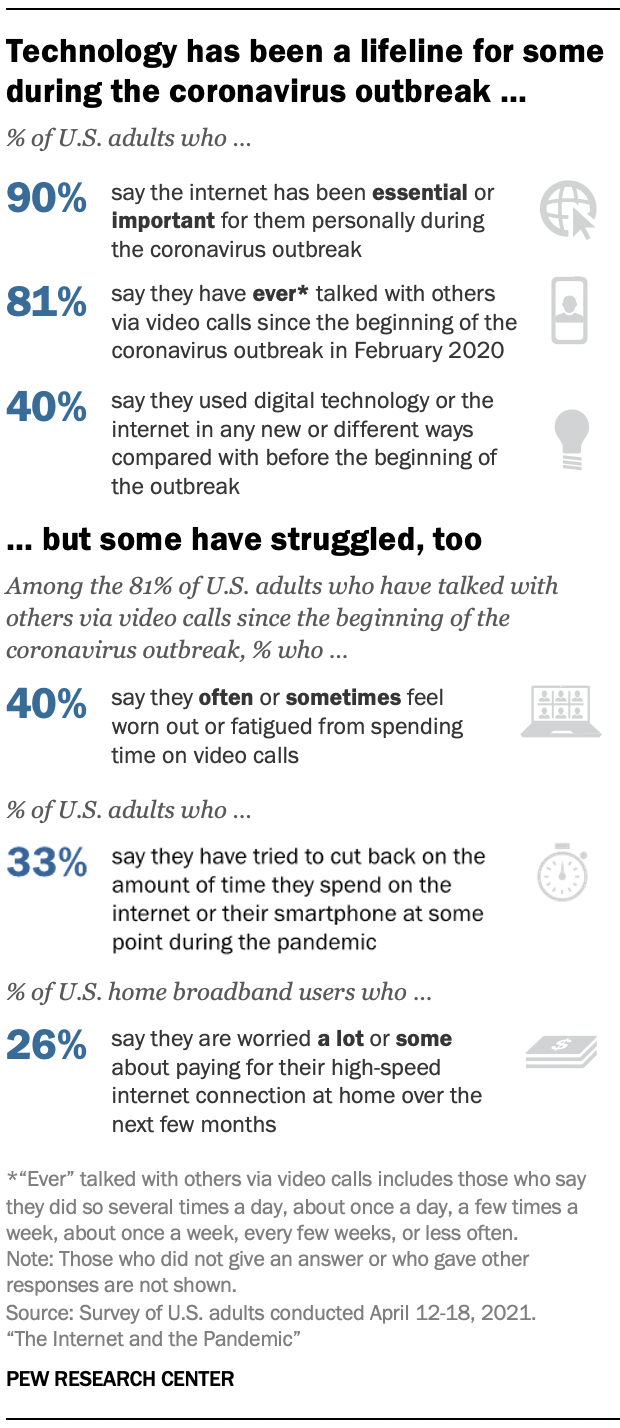

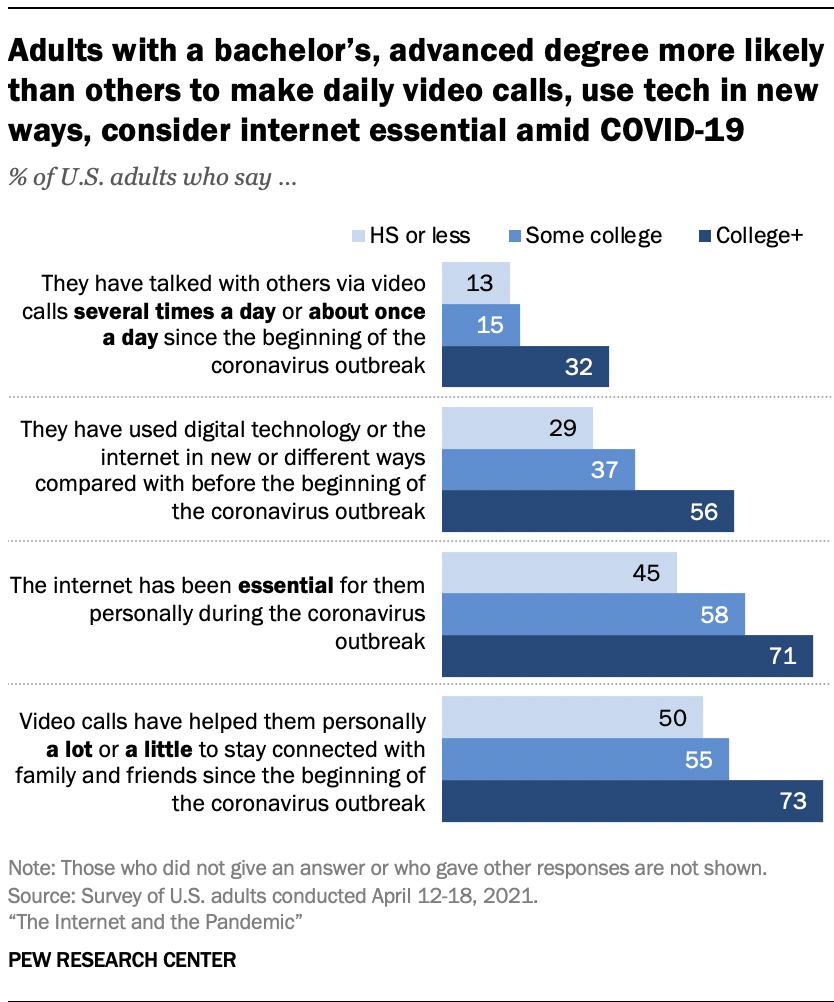

The vast majority of adults (90%) say the internet has been at least important to them personally during the pandemic, the survey finds. The share who say it has been essential – 58% – is up slightly from 53% in April 2020. There have also been upticks in the shares who say the internet has been essential in the past year among those with a bachelor’s degree or more formal education, adults under 30, and those 65 and older.

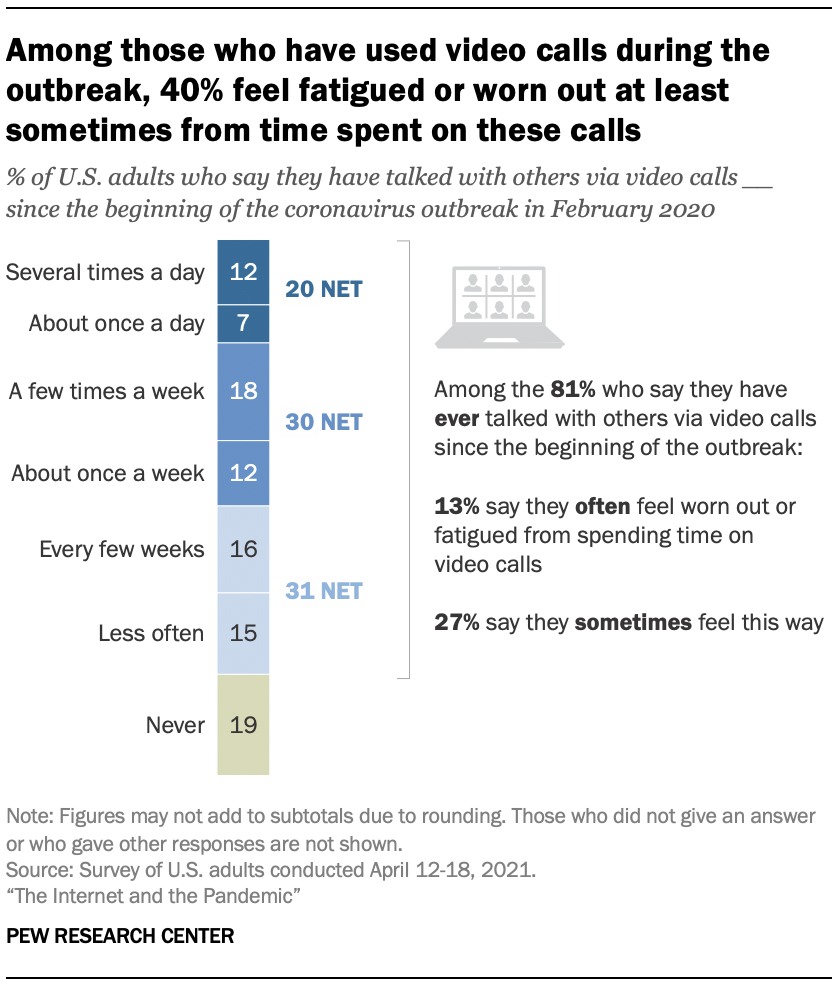

A large majority of Americans (81%) also say they talked with others via video calls at some point since the pandemic’s onset. And for 40% of Americans, digital tools have taken on new relevance: They report they used technology or the internet in ways that were new or different to them. Some also sought upgrades to their service as the pandemic unfolded: 29% of broadband users did something to improve the speed, reliability or quality of their high-speed internet connection at home since the beginning of the outbreak.

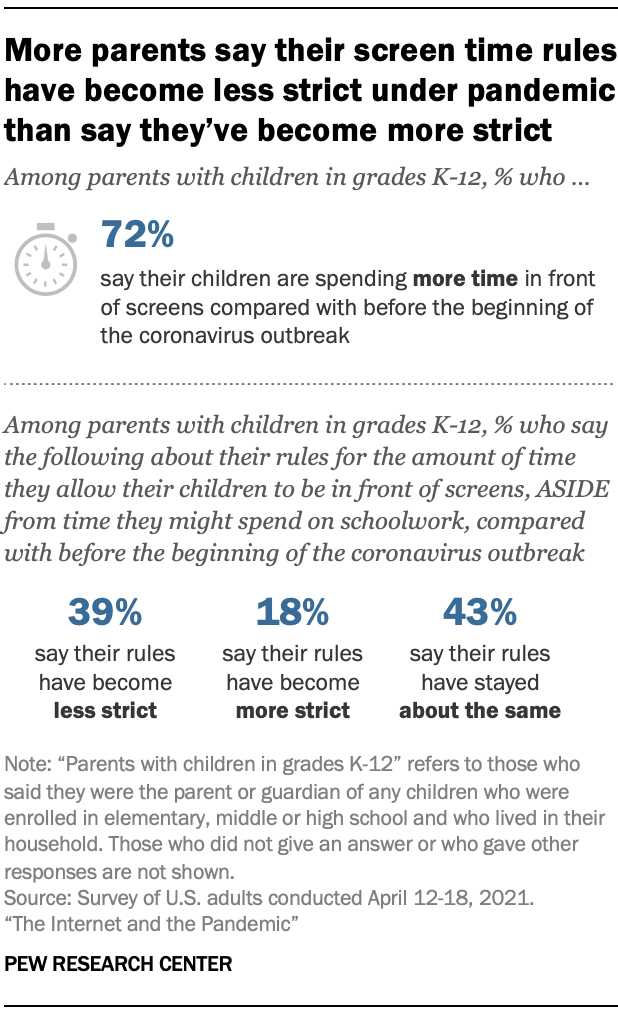

Still, tech use has not been an unmitigated boon for everyone. “ Zoom fatigue ” was widely speculated to be a problem in the pandemic, and some Americans report related experiences in the new survey: 40% of those who have ever talked with others via video calls since the beginning of the pandemic say they have felt worn out or fatigued often or sometimes by the time they spend on them. Moreover, changes in screen time occurred for Americans generally and for parents of young children . The survey finds that a third of all adults say they tried to cut back on time spent on their smartphone or the internet at some point during the pandemic. In addition, 72% of parents of children in grades K-12 say their kids are spending more time on screens compared with before the outbreak. 1

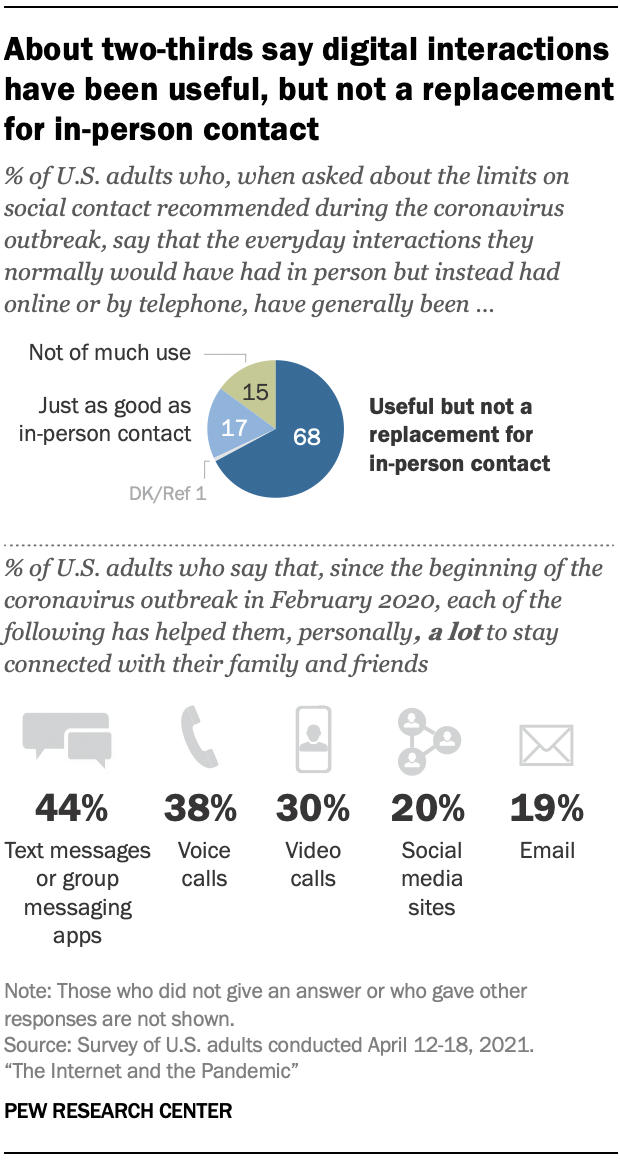

For many, digital interactions could only do so much as a stand-in for in-person communication. About two-thirds of Americans (68%) say the interactions they would have had in person, but instead had online or over the phone, have generally been useful – but not a replacement for in-person contact. Another 15% say these tools haven’t been of much use in their interactions. Still, 17% report that these digital interactions have been just as good as in-person contact.

Some types of technology have been more helpful than others for Americans. For example, 44% say text messages or group messaging apps have helped them a lot to stay connected with family and friends, 38% say the same about voice calls and 30% say this about video calls. Smaller shares say social media sites (20%) and email (19%) have helped them in this way.

The survey offers a snapshot of Americans’ lives just over one year into the pandemic as they reflected back on what had happened. It is important to note the findings were gathered in April 2021, just before all U.S. adults became eligible for coronavirus vaccine s. At the time, some states were beginning to loosen restrictions on businesses and social encounters. This survey also was fielded before the delta variant became prominent in the United States, raising concerns about new and evolving variants .

Here are some of the key takeaways from the survey.

Americans’ tech experiences in the pandemic are linked to digital divides, tech readiness

Some Americans’ experiences with technology haven’t been smooth or easy during the pandemic. The digital divides related to internet use and affordability were highlighted by the pandemic and also emerged in new ways as life moved online.

For all Americans relying on screens during the pandemic, connection quality has been important for school assignments, meetings and virtual social encounters alike. The new survey highlights difficulties for some: Roughly half of those who have a high-speed internet connection at home (48%) say they have problems with the speed, reliability or quality of their home connection often or sometimes. 2

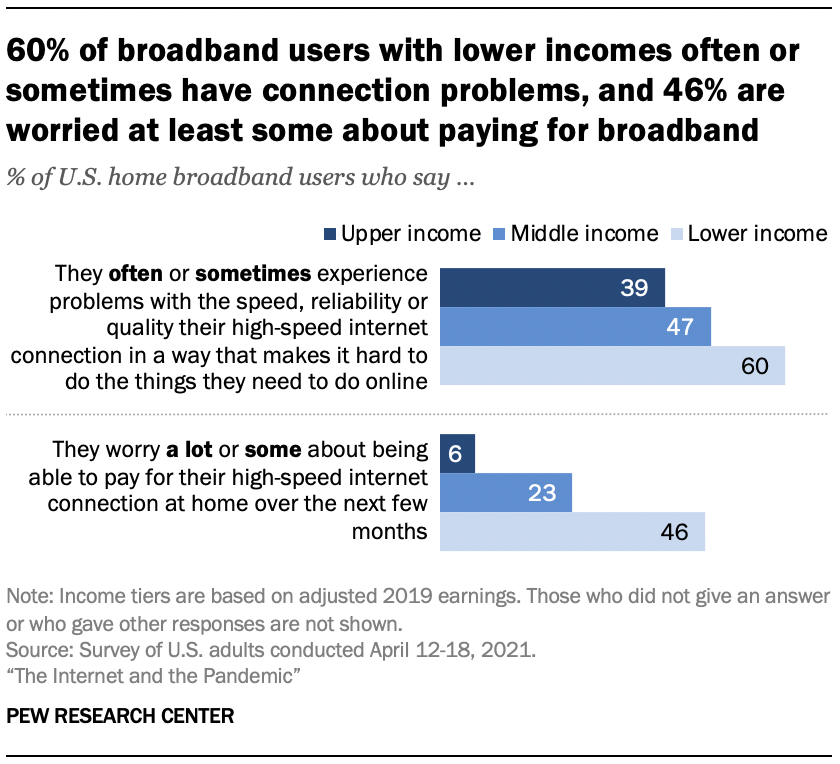

Beyond that, affordability remained a persistent concern for a portion of digital tech users as the pandemic continued – about a quarter of home broadband users (26%) and smartphone owners (24%) said in the April 2021 survey that they worried a lot or some about paying their internet and cellphone bills over the next few months.

From parents of children facing the “ homework gap ” to Americans struggling to afford home internet , those with lower incomes have been particularly likely to struggle. At the same time, some of those with higher incomes have been affected as well.

Affordability and connection problems have hit broadband users with lower incomes especially hard. Nearly half of broadband users with lower incomes, and about a quarter of those with midrange incomes, say that as of April they were at least somewhat worried about paying their internet bill over the next few months. 3 And home broadband users with lower incomes are roughly 20 points more likely to say they often or sometimes experience problems with their connection than those with relatively high incomes. Still, 55% of those with lower incomes say the internet has been essential to them personally in the pandemic.

At the same time, Americans’ levels of formal education are associated with their experiences turning to tech during the pandemic.

Those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree are about twice as likely as those with a high school diploma or less formal education to have used tech in new or different ways during the pandemic. There is also roughly a 20 percentage point gap between these two groups in the shares who have made video calls about once a day or more often and who say these calls have helped at least a little to stay connected with family and friends. And 71% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more education say the internet has been essential, compared with 45% of those with a high school diploma or less.

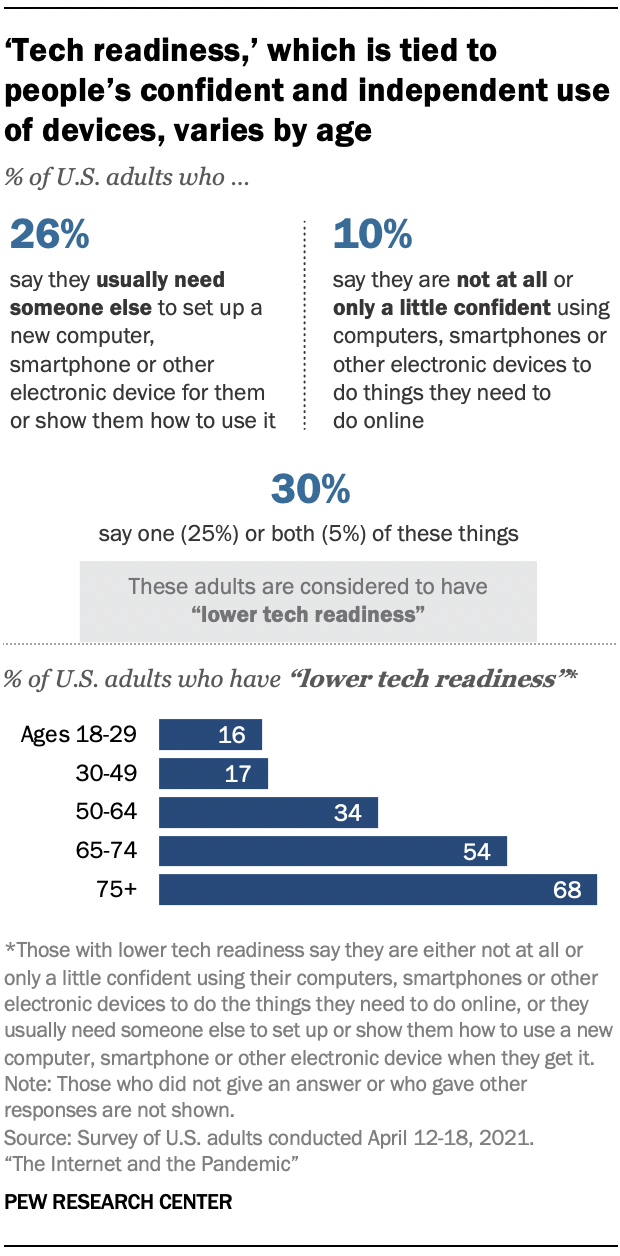

More broadly, not all Americans believe they have key tech skills. In this survey, about a quarter of adults (26%) say they usually need someone else’s help to set up or show them how to use a new computer, smartphone or other electronic device. And one-in-ten report they have little to no confidence in their ability to use these types of devices to do the things they need to do online. This report refers to those who say they experience either or both of these issues as having “lower tech readiness.” Some 30% of adults fall in this category. (A full description of how this group was identified can be found in Chapter 3. )

These struggles are particularly acute for older adults, some of whom have had to learn new tech skills over the course of the pandemic. Roughly two-thirds of adults 75 and older fall into the group having lower tech readiness – that is, they either have little or no confidence in their ability to use their devices, or generally need help setting up and learning how to use new devices. Some 54% of Americans ages 65 to 74 are also in this group.

Americans with lower tech readiness have had different experiences with technology during the pandemic. While 82% of the Americans with lower tech readiness say the internet has been at least important to them personally during the pandemic, they are less likely than those with higher tech readiness to say the internet has been essential (39% vs. 66%). Some 21% of those with lower tech readiness say digital interactions haven’t been of much use in standing in for in-person contact, compared with 12% of those with higher tech readiness.

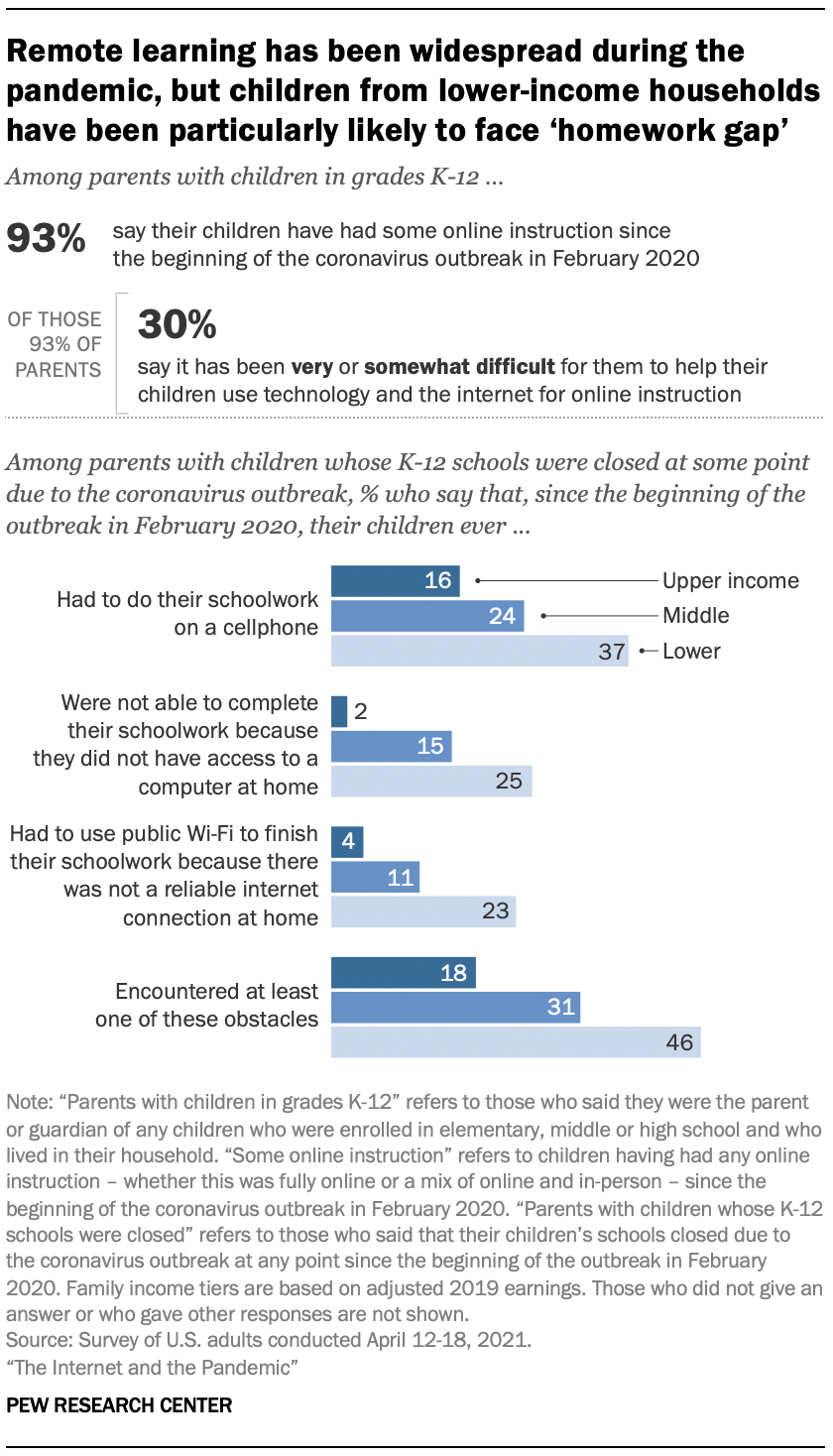

46% of parents with lower incomes whose children faced school closures say their children had at least one problem related to the ‘homework gap’

As school moved online for many families, parents and their children experienced profound changes. Fully 93% of parents with K-12 children at home say these children had some online instruction during the pandemic. Among these parents, 62% report that online learning has gone very or somewhat well, and 70% say it has been very or somewhat easy for them to help their children use technology for online instruction.

Still, 30% of the parents whose children have had online instruction during the pandemic say it has been very or somewhat difficult for them to help their children use technology or the internet for this.

The survey also shows that children from households with lower incomes who faced school closures in the pandemic have been especially likely to encounter tech-related obstacles in completing their schoolwork – a phenomenon contributing to the “ homework gap .”

Overall, about a third (34%) of all parents whose children’s schools closed at some point say their children have encountered at least one of the tech-related issues we asked about amid COVID-19: having to do schoolwork on a cellphone, being unable to complete schoolwork because of lack of computer access at home, or having to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because there was no reliable connection at home.

This share is higher among parents with lower incomes whose children’s schools closed. Nearly half (46%) say their children have faced at least one of these issues. Some with higher incomes were affected as well – about three-in-ten (31%) of these parents with midrange incomes say their children faced one or more of these issues, as do about one-in-five of these parents with higher household incomes.

Prior Center work has documented this “ homework gap ” in other contexts – both before the coronavirus outbreak and near the beginning of the pandemic . In April 2020, for example, parents with lower incomes were particularly likely to think their children would face these struggles amid the outbreak.

Besides issues related to remote schooling, other changes were afoot in families as the pandemic forced many families to shelter in place. For instance, parents’ estimates of their children’s screen time – and family rules around this – changed in some homes. About seven-in-ten parents with children in kindergarten through 12th grade (72%) say their children were spending more time on screens as of the April survey compared with before the outbreak. Some 39% of parents with school-age children say they have become less strict about screen time rules during the outbreak. About one-in-five (18%) say they have become more strict, while 43% have kept screen time rules about the same.

More adults now favor the idea that schools should provide digital technology to all students during the pandemic than did in April 2020

Americans’ tech struggles related to digital divides gained attention from policymakers and news organizations as the pandemic progressed.

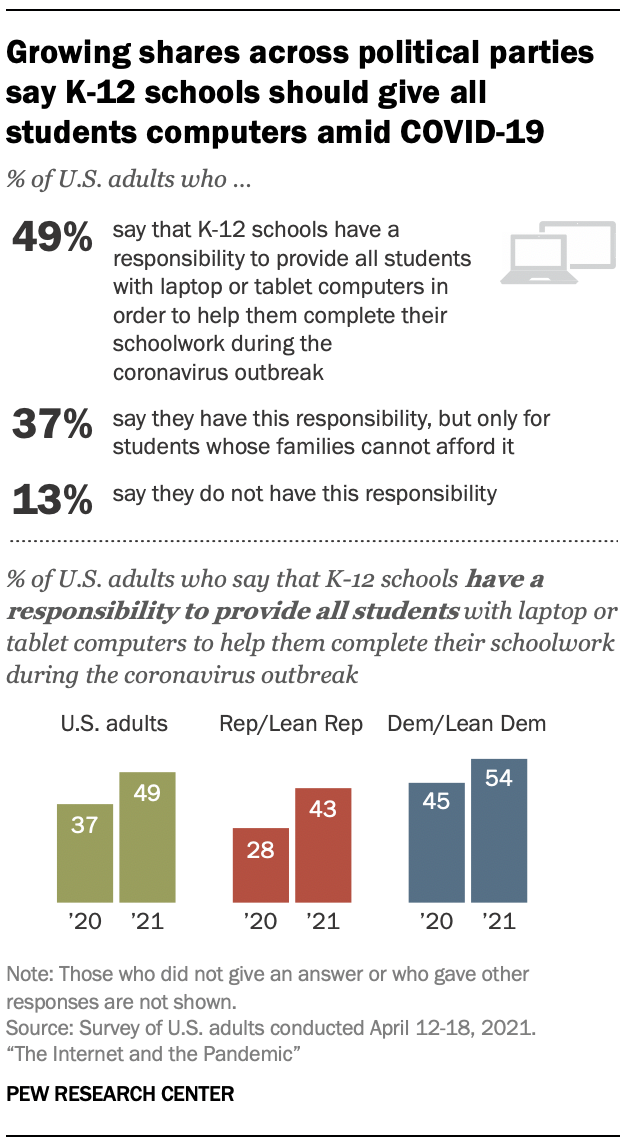

On some policy issues, public attitudes changed over the course of the outbreak – for example, views on what K-12 schools should provide to students shifted. Some 49% now say K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide all students with laptop or tablet computers in order to help them complete their schoolwork during the pandemic, up 12 percentage points from a year ago.

The shares of those who say so have increased for both major political parties over the past year: This view shifted 15 points for Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP, and there was a 9-point increase for Democrats and Democratic leaners.

However, when it comes to views of policy solutions for internet access more generally, not much has changed. Some 37% of Americans say that the government has a responsibility to ensure all Americans have high-speed internet access during the outbreak, and the overall share is unchanged from April 2020 – the first time Americans were asked this specific question about the government’s pandemic responsibility to provide internet access. 4

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say the government has this responsibility, and within the Republican Party, those with lower incomes are more likely to say this than their counterparts earning more money.

Video calls and conferencing have been part of everyday life

Americans’ own words provide insight into exactly how their lives changed amid COVID-19. When asked to describe the new or different ways they had used technology, some Americans mention video calls and conferencing facilitating a variety of virtual interactions – including attending events like weddings, family holidays and funerals or transforming where and how they worked. 5 From family calls, shopping for groceries and placing takeout orders online to having telehealth visits with medical professionals or participating in online learning activities, some aspects of life have been virtually transformed:

“I’ve gone from not even knowing remote programs like Zoom even existed, to using them nearly every day.” – Man, 54

“[I’ve been] h andling … deaths of family and friends remotely, attending and sharing classical music concerts and recitals with other professionals, viewing [my] own church services and Bible classes, shopping. … Basically, [the internet has been] a lifeline.” – Woman, 69

“I … use Zoom for church youth activities. [I] use Zoom for meetings. I order groceries and takeout food online. We arranged for a ‘digital reception’ for my daughter’s wedding as well as live streaming the event.” – Woman, 44

When asked about video calls specifically, half of Americans report they have talked with others in this way at least once a week since the beginning of the outbreak; one-in-five have used these platforms daily. But how often people have experienced this type of digital connectedness varies by age. For example, about a quarter of adults ages 18 to 49 (27%) say they have connected with others on video calls about once a day or more often, compared with 16% of those 50 to 64 and just 7% of those 65 and older.

Even as video technology became a part of life for users, many accounts of burnout surfaced and some speculated that “Zoom fatigue” was setting in as Americans grew weary of this type of screen time. The survey finds that some 40% of those who participated in video calls since the beginning of the pandemic – a third of all Americans – say they feel worn out or fatigued often or sometimes from the time they spend on video calls. About three-quarters of those who have been on these calls several times a day in the pandemic say this.

Fatigue is not limited to frequent users, however: For example, about a third (34%) of those who have made video calls about once a week say they feel worn out at least sometimes.

These are among the main findings from the survey. Other key results include:

Some Americans’ personal lives and social relationships have changed during the pandemic: Some 36% of Americans say their own personal lives changed in a major way as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. Another 47% say their personal lives changed, but only a little bit. About half (52%) of those who say major change has occurred in their personal lives due to the pandemic also say they have used tech in new ways, compared with about four-in-ten (38%) of those whose personal lives changed a little bit and roughly one-in-five (19%) of those who say their personal lives stayed about the same.

Even as tech helped some to stay connected, a quarter of Americans say they feel less close to close family members now compared with before the pandemic, and about four-in-ten (38%) say the same about friends they know well. Roughly half (53%) say this about casual acquaintances.

The majority of those who tried to sign up for vaccine appointments in the first part of the year went online to do so: Despite early problems with vaccine rollout and online registration systems , in the April survey tech problems did not appear to be major struggles for most adults who had tried to sign up online for COVID-19 vaccines. The survey explored Americans’ experiences getting these vaccine appointments and reveals that in April 57% of adults had tried to sign themselves up and 25% had tried to sign someone else up. Fully 78% of those who tried to sign themselves up and 87% of those who tried to sign others up were online registrants.

When it comes to difficulties with the online vaccine signup process, 29% of those who had tried to sign up online – 13% of all Americans – say it was very or somewhat difficult to sign themselves up for vaccines at that time. Among five reasons for this that the survey asked about, the most common major reason was lack of available appointments, rather than tech-related problems. Adults 65 and older who tried to sign themselves up for the vaccine online were the most likely age group to experience at least some difficulty when they tried to get a vaccine appointment.

Tech struggles and usefulness alike vary by race and ethnicity. Americans’ experiences also have varied across racial and ethnic groups. For example, Black Americans are more likely than White or Hispanic adults to meet the criteria for having “lower tech readiness.” 6 Among broadband users, Black and Hispanic adults were also more likely than White adults to be worried about paying their bills for their high-speed internet access at home as of April, though the share of Hispanic Americans who say this declined sharply since April 2020. And a majority of Black and Hispanic broadband users say they at least sometimes have experienced problems with their internet connection.

Still, Black adults and Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to say various technologies – text messages, voice calls, video calls, social media sites and email – have helped them a lot to stay connected with family and friends amid the pandemic.

Tech has helped some adults under 30 to connect with friends, but tech fatigue also set in for some. Only about one-in-five adults ages 18 to 29 say they feel closer to friends they know well compared with before the pandemic. This share is twice as high as that among adults 50 and older. Adults under 30 are also more likely than any other age group to say social media sites have helped a lot in staying connected with family and friends (30% say so), and about four-in-ten of those ages 18 to 29 say this about video calls.

Screen time affected some negatively, however. About six-in-ten adults under 30 (57%) who have ever made video calls in the pandemic say they at least sometimes feel worn out or fatigued from spending time on video calls, and about half (49%) of young adults say they have tried to cut back on time spent on the internet or their smartphone.

- Throughout this report, “parents” refers to those who said they were the parent or guardian of any children who were enrolled in elementary, middle or high school and who lived in their household at the time of the survey. ↩

- People with a high-speed internet connection at home also are referred to as “home broadband users” or “broadband users” throughout this report. ↩

- Family incomes are based on 2019 earnings and adjusted for differences in purchasing power by geographic region and for household sizes. Middle income is defined here as two-thirds to double the median annual family income for all panelists on the American Trends Panel. Lower income falls below that range; upper income falls above it. ↩

- A separate Center study also fielded in April 2021 asked Americans what the government is responsible for on a number of topics, but did not mention the coronavirus outbreak. Some 43% of Americans said in that survey that the federal government has a responsibility to provide high-speed internet for all Americans. This was a significant increase from 2019, the last time the Center had asked that more general question, when 28% said the same. ↩

- Quotations in this report may have been lightly edited for grammar, spelling and clarity. ↩

- There were not enough Asian American respondents in the sample to be broken out into a separate analysis. As always, their responses are incorporated into the general population figures throughout this report. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Business & Workplace

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- COVID-19 & Technology

- Digital Divide

- Education & Learning Online

A look at small businesses in the U.S.

Majorities of adults see decline of union membership as bad for the u.s. and working people, a look at black-owned businesses in the u.s., from businesses and banks to colleges and churches: americans’ views of u.s. institutions, 2023 saw some of the biggest, hardest-fought labor disputes in recent decades, most popular, report materials.

- American Trends Panel Wave 88

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

From Science to Arts, an Inevitable Decision?

The wonderful world of fungi, openmind books, scientific anniversaries, simultaneous translation technology – ever closer to reality, featured author, latest book, the impact of the internet on society: a global perspective, introduction.

The Internet is the decisive technology of the Information Age, as the electrical engine was the vector of technological transformation of the Industrial Age. This global network of computer networks, largely based nowadays on platforms of wireless communication, provides ubiquitous capacity of multimodal, interactive communication in chosen time, transcending space. The Internet is not really a new technology: its ancestor, the Arpanet, was first deployed in 1969 (Abbate 1999). But it was in the 1990s when it was privatized and released from the control of the U.S. Department of Commerce that it diffused around the world at extraordinary speed: in 1996 the first survey of Internet users counted about 40 million; in 2013 they are over 2.5 billion, with China accounting for the largest number of Internet users. Furthermore, for some time the spread of the Internet was limited by the difficulty to lay out land-based telecommunications infrastructure in the emerging countries. This has changed with the explosion of wireless communication in the early twenty-first century. Indeed, in 1991, there were about 16 million subscribers of wireless devices in the world, in 2013 they are close to 7 billion (in a planet of 7.7 billion human beings). Counting on the family and village uses of mobile phones, and taking into consideration the limited use of these devices among children under five years of age, we can say that humankind is now almost entirely connected, albeit with great levels of inequality in the bandwidth as well as in the efficiency and price of the service.

At the heart of these communication networks the Internet ensures the production, distribution, and use of digitized information in all formats. According to the study published by Martin Hilbert in Science (Hilbert and López 2011), 95 percent of all information existing in the planet is digitized and most of it is accessible on the Internet and other computer networks.

The speed and scope of the transformation of our communication environment by Internet and wireless communication has triggered all kind of utopian and dystopian perceptions around the world.

As in all moments of major technological change, people, companies, and institutions feel the depth of the change, but they are often overwhelmed by it, out of sheer ignorance of its effects.

The media aggravate the distorted perception by dwelling into scary reports on the basis of anecdotal observation and biased commentary. If there is a topic in which social sciences, in their diversity, should contribute to the full understanding of the world in which we live, it is precisely the area that has come to be named in academia as Internet Studies. Because, in fact, academic research knows a great deal on the interaction between Internet and society, on the basis of methodologically rigorous empirical research conducted in a plurality of cultural and institutional contexts. Any process of major technological change generates its own mythology. In part because it comes into practice before scientists can assess its effects and implications, so there is always a gap between social change and its understanding. For instance, media often report that intense use of the Internet increases the risk of alienation, isolation, depression, and withdrawal from society. In fact, available evidence shows that there is either no relationship or a positive cumulative relationship between the Internet use and the intensity of sociability. We observe that, overall, the more sociable people are, the more they use the Internet. And the more they use the Internet, the more they increase their sociability online and offline, their civic engagement, and the intensity of family and friendship relationships, in all cultures—with the exception of a couple of early studies of the Internet in the 1990s, corrected by their authors later (Castells 2001; Castells et al. 2007; Rainie and Wellman 2012; Center for the Digital Future 2012 et al.).

Thus, the purpose of this chapter will be to summarize some of the key research findings on the social effects of the Internet relying on the evidence provided by some of the major institutions specialized in the social study of the Internet. More specifically, I will be using the data from the world at large: the World Internet Survey conducted by the Center for the Digital Future, University of Southern California; the reports of the British Computer Society (BCS), using data from the World Values Survey of the University of Michigan; the Nielsen reports for a variety of countries; and the annual reports from the International Telecommunications Union. For data on the United States, I have used the Pew American Life and Internet Project of the Pew Institute. For the United Kingdom, the Oxford Internet Survey from the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, as well as the Virtual Society Project from the Economic and Social Science Research Council. For Spain, the Project Internet Catalonia of the Internet Interdisciplinary Institute (IN3) of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC); the various reports on the information society from Telefónica; and from the Orange Foundation. For Portugal, the Observatório de Sociedade da Informação e do Conhecimento (OSIC) in Lisbon. I would like to emphasize that most of the data in these reports converge toward similar trends. Thus I have selected for my analysis the findings that complement and reinforce each other, offering a consistent picture of the human experience on the Internet in spite of the human diversity.

Given the aim of this publication to reach a broad audience, I will not present in this text the data supporting the analysis presented here. Instead, I am referring the interested reader to the web sources of the research organizations mentioned above, as well as to selected bibliographic references discussing the empirical foundation of the social trends reported here.

Technologies of Freedom, the Network Society, and the Culture of Autonomy

In order to fully understand the effects of the Internet on society, we should remember that technology is material culture. It is produced in a social process in a given institutional environment on the basis of the ideas, values, interests, and knowledge of their producers, both their early producers and their subsequent producers. In this process we must include the users of the technology, who appropriate and adapt the technology rather than adopting it, and by so doing they modify it and produce it in an endless process of interaction between technological production and social use. So, to assess the relevance of Internet in society we must recall the specific characteristics of Internet as a technology. Then we must place it in the context of the transformation of the overall social structure, as well as in relationship to the culture characteristic of this social structure. Indeed, we live in a new social structure, the global network society, characterized by the rise of a new culture, the culture of autonomy.

Internet is a technology of freedom, in the terms coined by Ithiel de Sola Pool in 1973, coming from a libertarian culture, paradoxically financed by the Pentagon for the benefit of scientists, engineers, and their students, with no direct military application in mind (Castells 2001). The expansion of the Internet from the mid-1990s onward resulted from the combination of three main factors:

- The technological discovery of the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee and his willingness to distribute the source code to improve it by the open-source contribution of a global community of users, in continuity with the openness of the TCP/IP Internet protocols. The web keeps running under the same principle of open source. And two-thirds of web servers are operated by Apache, an open-source server program.

- Institutional change in the management of the Internet, keeping it under the loose management of the global Internet community, privatizing it, and allowing both commercial uses and cooperative uses.

- Major changes in social structure, culture, and social behavior: networking as a prevalent organizational form; individuation as the main orientation of social behavior; and the culture of autonomy as the culture of the network society.

I will elaborate on these major trends.

Our society is a network society; that is, a society constructed around personal and organizational networks powered by digital networks and communicated by the Internet. And because networks are global and know no boundaries, the network society is a global network society. This historically specific social structure resulted from the interaction between the emerging technological paradigm based on the digital revolution and some major sociocultural changes. A primary dimension of these changes is what has been labeled the rise of the Me-centered society, or, in sociological terms, the process of individuation, the decline of community understood in terms of space, work, family, and ascription in general. This is not the end of community, and not the end of place-based interaction, but there is a shift toward the reconstruction of social relationships, including strong cultural and personal ties that could be considered a form of community, on the basis of individual interests, values, and projects.

The process of individuation is not just a matter of cultural evolution, it is materially produced by the new forms of organizing economic activities, and social and political life, as I analyzed in my trilogy on the Information Age (Castells 1996–2003). It is based on the transformation of space (metropolitan life), work and economic activity (rise of the networked enterprise and networked work processes), culture and communication (shift from mass communication based on mass media to mass self-communication based on the Internet); on the crisis of the patriarchal family, with increasing autonomy of its individual members; the substitution of media politics for mass party politics; and globalization as the selective networking of places and processes throughout the planet.

But individuation does not mean isolation, or even less the end of community. Sociability is reconstructed as networked individualism and community through a quest for like-minded individuals in a process that combines online interaction with offline interaction, cyberspace and the local space. Individuation is the key process in constituting subjects (individual or collective), networking is the organizational form constructed by these subjects; this is the network society, and the form of sociability is what Rainie and Wellman (2012) conceptualized as networked individualism. Network technologies are of course the medium for this new social structure and this new culture (Papacharissi 2010).

As stated above, academic research has established that the Internet does not isolate people, nor does it reduce their sociability; it actually increases sociability, as shown by myself in my studies in Catalonia (Castells 2007), Rainie and Wellman in the United States (2012), Cardoso in Portugal (2010), and the World Internet Survey for the world at large (Center for the Digital Future 2012 et al.). Furthermore, a major study by Michael Willmott for the British Computer Society (Trajectory Partnership 2010) has shown a positive correlation, for individuals and for countries, between the frequency and intensity of the use of the Internet and the psychological indicators of personal happiness. He used global data for 35,000 people obtained from the World Wide Survey of the University of Michigan from 2005 to 2007. Controlling for other factors, the study showed that Internet use empowers people by increasing their feelings of security, personal freedom, and influence, all feelings that have a positive effect on happiness and personal well-being. The effect is particularly positive for people with lower income and who are less qualified, for people in the developing world, and for women. Age does not affect the positive relationship; it is significant for all ages. Why women? Because they are at the center of the network of their families, Internet helps them to organize their lives. Also, it helps them to overcome their isolation, particularly in patriarchal societies. The Internet also contributes to the rise of the culture of autonomy.

The key for the process of individuation is the construction of autonomy by social actors, who become subjects in the process. They do so by defining their specific projects in interaction with, but not submission to, the institutions of society. This is the case for a minority of individuals, but because of their capacity to lead and mobilize they introduce a new culture in every domain of social life: in work (entrepreneurship), in the media (the active audience), in the Internet (the creative user), in the market (the informed and proactive consumer), in education (students as informed critical thinkers, making possible the new frontier of e-learning and m-learning pedagogy), in health (the patient-centered health management system) in e-government (the informed, participatory citizen), in social movements (cultural change from the grassroots, as in feminism or environmentalism), and in politics (the independent-minded citizen able to participate in self-generated political networks).

There is increasing evidence of the direct relationship between the Internet and the rise of social autonomy. From 2002 to 2007 I directed in Catalonia one of the largest studies ever conducted in Europe on the Internet and society, based on 55,000 interviews, one-third of them face to face (IN3 2002–07). As part of this study, my collaborators and I compared the behavior of Internet users to non-Internet users in a sample of 3,000 people, representative of the population of Catalonia. Because in 2003 only about 40 percent of people were Internet users we could really compare the differences in social behavior for users and non-users, something that nowadays would be more difficult given the 79 percent penetration rate of the Internet in Catalonia. Although the data are relatively old, the findings are not, as more recent studies in other countries (particularly in Portugal) appear to confirm the observed trends. We constructed scales of autonomy in different dimensions. Only between 10 and 20 percent of the population, depending on dimensions, were in the high level of autonomy. But we focused on this active segment of the population to explore the role of the Internet in the construction of autonomy. Using factor analysis we identified six major types of autonomy based on projects of individuals according to their practices:

a) professional development b) communicative autonomy c) entrepreneurship d) autonomy of the body e) sociopolitical participation f) personal, individual autonomy

These six types of autonomous practices were statistically independent among themselves. But each one of them correlated positively with Internet use in statistically significant terms, in a self-reinforcing loop (time sequence): the more one person was autonomous, the more she/he used the web, and the more she/he used the web, the more autonomous she/he became (Castells et al. 2007). This is a major empirical finding. Because if the dominant cultural trend in our society is the search for autonomy, and if the Internet powers this search, then we are moving toward a society of assertive individuals and cultural freedom, regardless of the barriers of rigid social organizations inherited from the Industrial Age. From this Internet-based culture of autonomy have emerged a new kind of sociability, networked sociability, and a new kind of sociopolitical practice, networked social movements and networked democracy. I will now turn to the analysis of these two fundamental trends at the source of current processes of social change worldwide.

The Rise of Social Network Sites on the Internet

Since 2002 (creation of Friendster, prior to Facebook) a new socio-technical revolution has taken place on the Internet: the rise of social network sites where now all human activities are present, from personal interaction to business, to work, to culture, to communication, to social movements, and to politics.

Social Network Sites are web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system.

(Boyd and Ellison 2007, 2)

Social networking uses, in time globally spent, surpassed e-mail in November 2007. It surpassed e-mail in number of users in July 2009. In terms of users it reached 1 billion by September 2010, with Facebook accounting for about half of it. In 2013 it has almost doubled, particularly because of increasing use in China, India, and Latin America. There is indeed a great diversity of social networking sites (SNS) by countries and cultures. Facebook, started for Harvard-only members in 2004, is present in most of the world, but QQ, Cyworld, and Baidu dominate in China; Orkut in Brazil; Mixi in Japan; etc. In terms of demographics, age is the main differential factor in the use of SNS, with a drop of frequency of use after 50 years of age, and particularly 65. But this is not just a teenager’s activity. The main Facebook U.S. category is in the age group 35–44, whose frequency of use of the site is higher than for younger people. Nearly 60 percent of adults in the U.S. have at least one SNS profile, 30 percent two, and 15 percent three or more. Females are as present as males, except when in a society there is a general gender gap. We observe no differences in education and class, but there is some class specialization of SNS, such as Myspace being lower than FB; LinkedIn is for professionals.

Thus, the most important activity on the Internet at this point in time goes through social networking, and SNS have become the chosen platforms for all kind of activities, not just personal friendships or chatting, but for marketing, e-commerce, education, cultural creativity, media and entertainment distribution, health applications, and sociopolitical activism. This is a significant trend for society at large. Let me explore the meaning of this trend on the basis of the still scant evidence.

Social networking sites are constructed by users themselves building on specific criteria of grouping. There is entrepreneurship in the process of creating sites, then people choose according to their interests and projects. Networks are tailored by people themselves with different levels of profiling and privacy. The key to success is not anonymity, but on the contrary, self-presentation of a real person connecting to real people (in some cases people are excluded from the SNS when they fake their identity). So, it is a self-constructed society by networking connecting to other networks. But this is not a virtual society. There is a close connection between virtual networks and networks in life at large. This is a hybrid world, a real world, not a virtual world or a segregated world.

People build networks to be with others, and to be with others they want to be with on the basis of criteria that include those people who they already know (a selected sub-segment). Most users go on the site every day. It is permanent connectivity. If we needed an answer to what happened to sociability in the Internet world, here it is:

There is a dramatic increase in sociability, but a different kind of sociability, facilitated and dynamized by permanent connectivity and social networking on the web.

Based on the time when Facebook was still releasing data (this time is now gone) we know that in 2009 users spent 500 billion minutes per month. This is not just about friendship or interpersonal communication. People do things together, share, act, exactly as in society, although the personal dimension is always there. Thus, in the U.S. 38 percent of adults share content, 21 percent remix, 14 percent blog, and this is growing exponentially, with development of technology, software, and SNS entrepreneurial initiatives. On Facebook, in 2009 the average user was connected to 60 pages, groups, and events, people interacted per month to 160 million objects (pages, groups, events), the average user created 70 pieces of content per month, and there were 25 billion pieces of content shared per month (web links, news stories, blogs posts, notes, photos). SNS are living spaces connecting all dimensions of people’s experience. This transforms culture because people share experience with a low emotional cost, while saving energy and effort. They transcend time and space, yet they produce content, set up links, and connect practices. It is a constantly networked world in every dimension of human experience. They co-evolve in permanent, multiple interaction. But they choose the terms of their co-evolution.

Thus, people live their physical lives but increasingly connect on multiple dimensions in SNS.

Paradoxically, the virtual life is more social than the physical life, now individualized by the organization of work and urban living.

But people do not live a virtual reality, indeed it is a real virtuality, since social practices, sharing, mixing, and living in society is facilitated in the virtuality, in what I called time ago the “space of flows” (Castells 1996).

Because people are increasingly at ease in the multi-textuality and multidimensionality of the web, marketers, work organizations, service agencies, government, and civil society are migrating massively to the Internet, less and less setting up alternative sites, more and more being present in the networks that people construct by themselves and for themselves, with the help of Internet social networking entrepreneurs, some of whom become billionaires in the process, actually selling freedom and the possibility of the autonomous construction of lives. This is the liberating potential of the Internet made material practice by these social networking sites. The largest of these social networking sites are usually bounded social spaces managed by a company. However, if the company tries to impede free communication it may lose many of its users, because the entry barriers in this industry are very low. A couple of technologically savvy youngsters with little capital can set up a site on the Internet and attract escapees from a more restricted Internet space, as happened to AOL and other networking sites of the first generation, and as could happen to Facebook or any other SNS if they are tempted to tinker with the rules of openness (Facebook tried to make users pay and retracted within days). So, SNS are often a business, but they are in the business of selling freedom, free expression, chosen sociability. When they tinker with this promise they risk their hollowing by net citizens migrating with their friends to more friendly virtual lands.

Perhaps the most telling expression of this new freedom is the transformation of sociopolitical practices on the Internet.

Communication Power: Mass-Self Communication and the Transformation of Politics

Power and counterpower, the foundational relationships of society, are constructed in the human mind, through the construction of meaning and the processing of information according to certain sets of values and interests (Castells 2009).

Ideological apparatuses and the mass media have been key tools of mediating communication and asserting power, and still are. But the rise of a new culture, the culture of autonomy, has found in Internet and mobile communication networks a major medium of mass self-communication and self-organization.

The key source for the social production of meaning is the process of socialized communication. I define communication as the process of sharing meaning through the exchange of information. Socialized communication is the one that exists in the public realm, that has the potential of reaching society at large. Therefore, the battle over the human mind is largely played out in the process of socialized communication. And this is particularly so in the network society, the social structure of the Information Age, which is characterized by the pervasiveness of communication networks in a multimodal hypertext.

The ongoing transformation of communication technology in the digital age extends the reach of communication media to all domains of social life in a network that is at the same time global and local, generic and customized, in an ever-changing pattern.

As a result, power relations, that is the relations that constitute the foundation of all societies, as well as the processes challenging institutionalized power relations, are increasingly shaped and decided in the communication field. Meaningful, conscious communication is what makes humans human. Thus, any major transformation in the technology and organization of communication is of utmost relevance for social change. Over the last four decades the advent of the Internet and of wireless communication has shifted the communication process in society at large from mass communication to mass self-communication. This is from a message sent from one to many with little interactivity to a system based on messages from many to many, multimodal, in chosen time, and with interactivity, so that senders are receivers and receivers are senders. And both have access to a multimodal hypertext in the web that constitutes the endlessly changing backbone of communication processes.

The transformation of communication from mass communication to mass self-communication has contributed decisively to alter the process of social change. As power relationships have always been based on the control of communication and information that feed the neural networks constitutive of the human mind, the rise of horizontal networks of communication has created a new landscape of social and political change by the process of disintermediation of the government and corporate controls over communication. This is the power of the network, as social actors build their own networks on the basis of their projects, values, and interests. The outcome of these processes is open ended and dependent on specific contexts. Freedom, in this case freedom of communicate, does not say anything on the uses of freedom in society. This is to be established by scholarly research. But we need to start from this major historical phenomenon: the building of a global communication network based on the Internet, a technology that embodies the culture of freedom that was at its source.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century there have been multiple social movements around the world that have used the Internet as their space of formation and permanent connectivity, among the movements and with society at large. These networked social movements, formed in the social networking sites on the Internet, have mobilized in the urban space and in the institutional space, inducing new forms of social movements that are the main actors of social change in the network society. Networked social movements have been particularly active since 2010, and especially in the Arab revolutions against dictatorships; in Europe and the U.S. as forms of protest against the management of the financial crisis; in Brazil; in Turkey; in Mexico; and in highly diverse institutional contexts and economic conditions. It is precisely the similarity of the movements in extremely different contexts that allows the formulation of the hypothesis that this is the pattern of social movements characteristic of the global network society. In all cases we observe the capacity of these movements for self-organization, without a central leadership, on the basis of a spontaneous emotional movement. In all cases there is a connection between Internet-based communication, mobile networks, and the mass media in different forms, feeding into each other and amplifying the movement locally and globally.

These movements take place in the context of exploitation and oppression, social tensions and social struggles; but struggles that were not able to successfully challenge the state in other instances of revolt are now powered by the tools of mass self-communication. It is not the technology that induces the movements, but without the technology (Internet and wireless communication) social movements would not take the present form of being a challenge to state power. The fact is that technology is material culture (ideas brought into the design) and the Internet materialized the culture of freedom that, as it has been documented, emerged on American campuses in the 1960s. This culture-made technology is at the source of the new wave of social movements that exemplify the depth of the global impact of the Internet in all spheres of social organization, affecting particularly power relationships, the foundation of the institutions of society. (See case studies and an analytical perspective on the interaction between Internet and networked social movements in Castells 2012.)

The Internet, as all technologies, does not produce effects by itself. Yet, it has specific effects in altering the capacity of the communication system to be organized around flows that are interactive, multimodal, asynchronous or synchronous, global or local, and from many to many, from people to people, from people to objects, and from objects to objects, increasingly relying on the semantic web. How these characteristics affect specific systems of social relationships has to be established by research, and this is what I tried to present in this text. What is clear is that without the Internet we would not have seen the large-scale development of networking as the fundamental mechanism of social structuring and social change in every domain of social life. The Internet, the World Wide Web, and a variety of networks increasingly based on wireless platforms constitute the technological infrastructure of the network society, as the electrical grid and the electrical engine were the support system for the form of social organization that we conceptualized as the industrial society. Thus, as a social construction, this technological system is open ended, as the network society is an open-ended form of social organization that conveys the best and the worse in humankind. Yet, the global network society is our society, and the understanding of its logic on the basis of the interaction between culture, organization, and technology in the formation and development of social and technological networks is a key field of research in the twenty-first century.

We can only make progress in our understanding through the cumulative effort of scholarly research. Only then we will be able to cut through the myths surrounding the key technology of our time. A digital communication technology that is already a second skin for young people, yet it continues to feed the fears and the fantasies of those who are still in charge of a society that they barely understand.

These references are in fact sources of more detailed references specific to each one of the topics analyzed in this text.

Abbate, Janet. A Social History of the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

Boyd, Danah M., and Nicole B. Ellison. “Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13, no. 1 (2007).

Cardoso, Gustavo, Angus Cheong, and Jeffrey Cole (eds). World Wide Internet: Changing Societies, Economies and Cultures. Macau: University of Macau Press, 2009.

Castells, Manuel. The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. 3 vols. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996–2003.

———. The Internet Galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, Business, and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

———. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

———. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2012.

Castells, Manuel, Imma Tubella, Teresa Sancho, and Meritxell Roca.

La transición a la sociedad red. Barcelona: Ariel, 2007.

Hilbert, Martin, and Priscilla López. “The World’s Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information.” Science 332, no. 6025 (April 1, 2011): pp. 60–65.

Papacharissi, Zizi, ed. The Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Networking Sites. Routledge, 2010.

Rainie. Lee, and Barry Wellman. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

Trajectory Partnership (Michael Willmott and Paul Flatters). The Information Dividend: Why IT Makes You “Happier.” Swindon: British Informatics Society Limited, 2010. http://www.bcs.org/upload/pdf/info-dividend-full-report.pdf

Selected Web References. Used as sources for analysis in the chapter

Agência para a Sociedade do Conhecimento. “Observatório de Sociedade da Informação e do Conhecimento (OSIC).” http://www.umic.pt/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=3026&Itemid=167

BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT. “Features, Press and Policy.” http://www.bcs.org/category/7307

Center for the Digital Future. The World Internet Project International Report. 4th ed. Los Angeles: USC Annenberg School, Center for the Digital Future, 2012. http://www.worldinternetproject.net/_files/_Published/_oldis/770_2012wip_report4th_ed.pdf

ESRC (Economic & Social Research Council). “Papers and Reports.” Virtual Society. http://virtualsociety.sbs.ox.ac.uk/reports.htm

Fundación Orange. “Análisis y Prospectiva: Informe eEspaña.” Fundación Orange. http://fundacionorange.es/fundacionorange/analisisprospectiva.html

Fundación Telefónica. “Informes SI.” Fundación Telefónica. http://sociedadinformacion.fundacion.telefonica.com/DYC/SHI/InformesSI/seccion=1190&idioma=es_ES.do

IN3 (Internet Interdisciplinary Institute). UOC. “Project Internet Catalonia (PIC): An Overview.” Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, 2002–07. http://www.uoc.edu/in3/pic/eng/

International Telecommunication Union. “Annual Reports.” http://www.itu.int/osg/spu/sfo/annual_reports/index.html

Nielsen Company. “Reports.” 2013. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/reports/2013.html?tag=Category:Media+ and+Entertainment

Oxford Internet Surveys. “Publications.” http://microsites.oii.ox.ac.uk/oxis/publications

Pew Internet & American Life Project. “Social Networking.” Pew Internet. http://www.pewinternet.org/Topics/Activities-and-Pursuits/Social-Networking.aspx?typeFilter=5

Related publications

- How the Internet Has Changed Everyday Life

- How Is the Internet Changing the Way We Work?

- Hyperhistory, the Emergence of the MASs, and the Design of Infraethics

Download Kindle

Download epub, download pdf, more publications related to this article, more about technology, artificial intelligence, digital world, visionaries, comments on this publication.

Morbi facilisis elit non mi lacinia lacinia. Nunc eleifend aliquet ipsum, nec blandit augue tincidunt nec. Donec scelerisque feugiat lectus nec congue. Quisque tristique tortor vitae turpis euismod, vitae aliquam dolor pretium. Donec luctus posuere ex sit amet scelerisque. Etiam sed neque magna. Mauris non scelerisque lectus. Ut rutrum ex porta, tristique mi vitae, volutpat urna.

Sed in semper tellus, eu efficitur ante. Quisque felis orci, fermentum quis arcu nec, elementum malesuada magna. Nulla vitae finibus ipsum. Aenean vel sapien a magna faucibus tristique ac et ligula. Sed auctor orci metus, vitae egestas libero lacinia quis. Nulla lacus sapien, efficitur mollis nisi tempor, gravida tincidunt sapien. In massa dui, varius vitae iaculis a, dignissim non felis. Ut sagittis pulvinar nisi, at tincidunt metus venenatis a. Ut aliquam scelerisque interdum. Mauris iaculis purus in nulla consequat, sed fermentum sapien condimentum. Aliquam rutrum erat lectus, nec placerat nisl mollis id. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Nam nisl nisi, efficitur et sem in, molestie vulputate libero. Quisque quis mattis lorem. Nunc quis convallis diam, id tincidunt risus. Donec nisl odio, convallis vel porttitor sit amet, lobortis a ante. Cras dapibus porta nulla, at laoreet quam euismod vitae. Fusce sollicitudin massa magna, eu dignissim magna cursus id. Quisque vel nisl tempus, lobortis nisl a, ornare lacus. Donec ac interdum massa. Curabitur id diam luctus, mollis augue vel, interdum risus. Nam vitae tortor erat. Proin quis tincidunt lorem.

The Internet, Politics and the Politics of Internet Debate

Do you want to stay up to date with our new publications.

Receive the OpenMind newsletter with all the latest contents published on our website

OpenMind Books

- The Search for Alternatives to Fossil Fuels

- View all books

About OpenMind

Connect with us.

- Keep up to date with our newsletter

Quote this content

Accessibility Links

- Skip to content

- Skip to search IOPscience

- Skip to Journals list

- Accessibility help

- Accessibility Help

Click here to close this panel.

Purpose-led Publishing is a coalition of three not-for-profit publishers in the field of physical sciences: AIP Publishing, the American Physical Society and IOP Publishing.

Together, as publishers that will always put purpose above profit, we have defined a set of industry standards that underpin high-quality, ethical scholarly communications.

We are proudly declaring that science is our only shareholder.

Effect of Internet on Student's Academic Performance and Social Life

E S Soegoto 1 and S Tjokroadiponto 2

Published under licence by IOP Publishing Ltd IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering , Volume 407 , International Conference on Informatics, Engineering, Science and Technology (INCITEST) 9 May 2018, Bandung, Indonesia Citation E S Soegoto and S Tjokroadiponto 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 407 012176 DOI 10.1088/1757-899X/407/1/012176

Article metrics

20601 Total downloads

Share this article

Author e-mails.

Author affiliations

1 Departement Management, Universitas Komputer Indonesia, Indonesia

2 Departement Teknik Dan Ilmu Komputer, Universitas Komputer Indonesia, Indonesia

Buy this article in print

The use of the internet has a huge impact on student achievement. This study was conducted to determine the effect of internet use on academic achievement, social life, and student activities in Bandung. This research will be very helpful for students, researchers, and curriculum developers to know the relationship of internet usage and academic achievement. This research was made by collecting the respondents from 2 Universities in Bandung, University Computer Indonesia and Institute Harapan Bangsa Technology. Respondents were randomly selected by 50 respondents. The results of this study can prove that the students' social life is influenced by the internet. Graphical representation of internet usage and its impact on students' social life shows that the use of the internet is very high, will minimize student social activity. This study shows that the use of the Internet for study purposes and academic achievement is directly proportional to each other while inversely proportional to student social life.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS