Medical Information

Delivery, Face Presentation, and Brow Presentation: Understanding Fetal Positions and Birth Scenarios

Introduction:.

During childbirth, the position of the baby plays a significant role in the delivery process. While the most common fetal presentation is the head-down position (vertex presentation), variations can occur, such as face presentation and brow presentation. This comprehensive article aims to provide a thorough understanding of delivery, face presentation, and brow presentation, including their definitions, causes, complications, and management approaches.

Delivery Process:

- Normal Vertex Presentation: In a typical delivery, the baby is positioned head-down, with the back of the head (occiput) leading the way through the birth canal.

- Engagement and Descent: Prior to delivery, the baby's head engages in the pelvis and gradually descends, preparing for birth.

- Cardinal Movements: The baby undergoes a series of cardinal movements, including flexion, internal rotation, extension, external rotation, and restitution, which facilitate the passage through the birth canal.

Face Presentation:

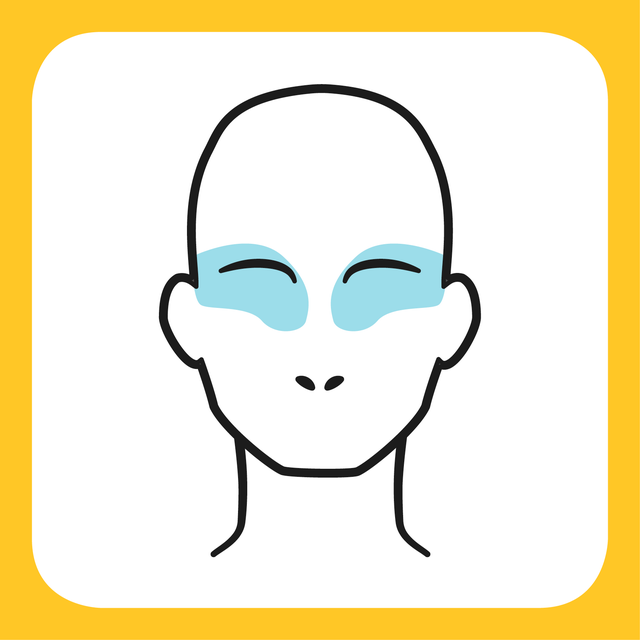

- Definition: Face presentation occurs when the baby's face is positioned to lead the way through the birth canal instead of the vertex (head).

- Causes: Face presentation can occur due to factors such as abnormal fetal positioning, multiple pregnancies, uterine abnormalities, or maternal pelvic anatomy.

- Complications: Face presentation is associated with an increased risk of prolonged labor, difficulties in delivery, increased fetal malposition, birth injuries, and the need for instrumental delivery.

- Management: The management of face presentation depends on several factors, including the progression of labor, the size of the baby, and the expertise of the healthcare provider. Options may include closely monitoring the progress of labor, attempting a vaginal delivery with careful maneuvers, or considering a cesarean section if complications arise.

Brow Presentation:

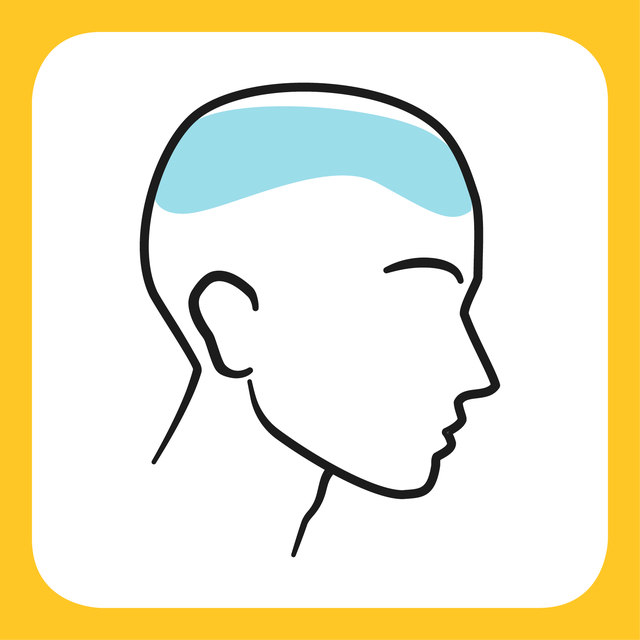

- Definition: Brow presentation occurs when the baby's head is partially extended, causing the brow (forehead) to lead the way through the birth canal.

- Causes: Brow presentation may result from abnormal fetal positioning, poor engagement of the fetal head, or other factors that prevent full flexion or extension.

- Complications: Brow presentation is associated with a higher risk of prolonged labor, difficulty in descent, increased chances of fetal head entrapment, birth injuries, and the potential need for instrumental delivery or cesarean section.

- Management: The management of brow presentation depends on various factors, such as cervical dilation, progress of labor, fetal size, and the presence of complications. Close monitoring, expert assessment, and a multidisciplinary approach may be necessary to determine the safest delivery method, which can include vaginal delivery with careful maneuvers, instrumental assistance, or cesarean section if warranted.

Delivery Techniques and Intervention:

- Obstetric Maneuvers: In certain situations, skilled healthcare providers may use obstetric maneuvers, such as manual rotation or the use of forceps or vacuum extraction, to facilitate delivery, reposition the baby, or prevent complications.

- Cesarean Section: In cases where vaginal delivery is not possible or poses risks to the mother or baby, a cesarean section may be performed to ensure a safe delivery.

Conclusion:

Delivery, face presentation, and brow presentation are important aspects of childbirth that require careful management and consideration. Understanding the definitions, causes, complications, and appropriate management approaches associated with these fetal positions can help healthcare providers ensure safe and successful deliveries. Individualized care, close monitoring, and multidisciplinary collaboration are crucial in optimizing maternal and fetal outcomes during these unique delivery scenarios.

Hashtags: #Delivery #FacePresentation #BrowPresentation #Childbirth #ObstetricDelivery

On the Article

Krish Tangella MD, MBA

Alexander Enabnit

Alexandra Warren

Please log in to post a comment.

Related Articles

Test your knowledge, asked by users, related centers, related specialties, related physicians, related procedures, related resources, join dovehubs.

and connect with fellow professionals

Related Directories

At DoveMed, our utmost priority is your well-being. We are an online medical resource dedicated to providing you with accurate and up-to-date information on a wide range of medical topics. But we're more than just an information hub - we genuinely care about your health journey. That's why we offer a variety of products tailored for both healthcare consumers and professionals, because we believe in empowering everyone involved in the care process. Our mission is to create a user-friendly healthcare technology portal that helps you make better decisions about your overall health and well-being. We understand that navigating the complexities of healthcare can be overwhelming, so we strive to be a reliable and compassionate companion on your path to wellness. As an impartial and trusted online resource, we connect healthcare seekers, physicians, and hospitals in a marketplace that promotes a higher quality, easy-to-use healthcare experience. You can trust that our content is unbiased and impartial, as it is trusted by physicians, researchers, and university professors around the globe. Importantly, we are not influenced or owned by any pharmaceutical, medical, or media companies. At DoveMed, we are a group of passionate individuals who deeply care about improving health and wellness for people everywhere. Your well-being is at the heart of everything we do.

For Patients

For professionals, for partners.

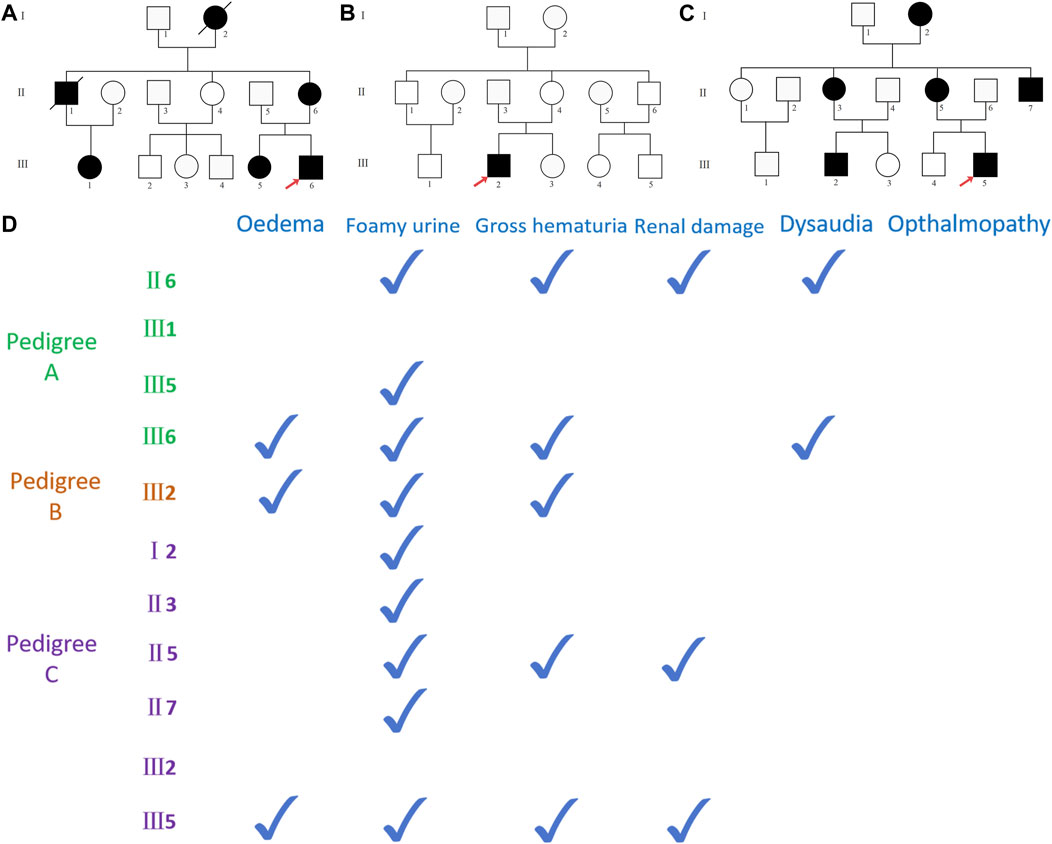

7.10 Brow presentation

Brow presentation constitutes an absolute foeto-pelvic disproportion, and vaginal delivery is impossible (except with preterm birth or extremely low birth weight).

This is an obstetric emergency, because labour is obstructed and there is a risk of uterine rupture and foetal distress.

7.10.1 Diagnosis

- Head is high; as with a face presentation, there is a cleft between the head and back, but it is less marked.

- the chin (it is not a face presentation),

- the posterior fontanelle (it is not a vertex presentation).

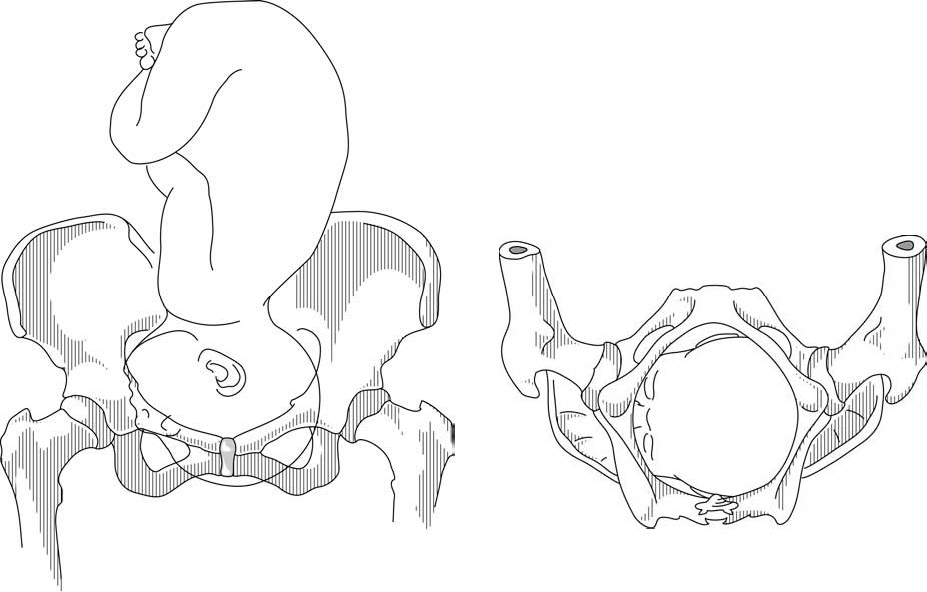

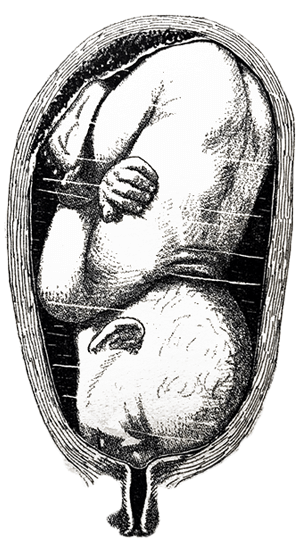

Figures 7.9 - Brow presentation

Any mobile presenting part can subsequently flex. The diagnosis of brow presentation is, therefore, not made until after the membranes have ruptured and the head has begun to engage in a fixed presentation. Some brow presentations will spontaneously convert to a vertex or, more rarely, a face presentation.

During delivery, the presenting part is slow to descend: the brow is becoming impacted.

7.10.2 Management

Foetus alive.

- Perform a caesarean section. When performing the caesarean section, an assistant must be ready to free the head by pushing it upward with a hand in the vagina.

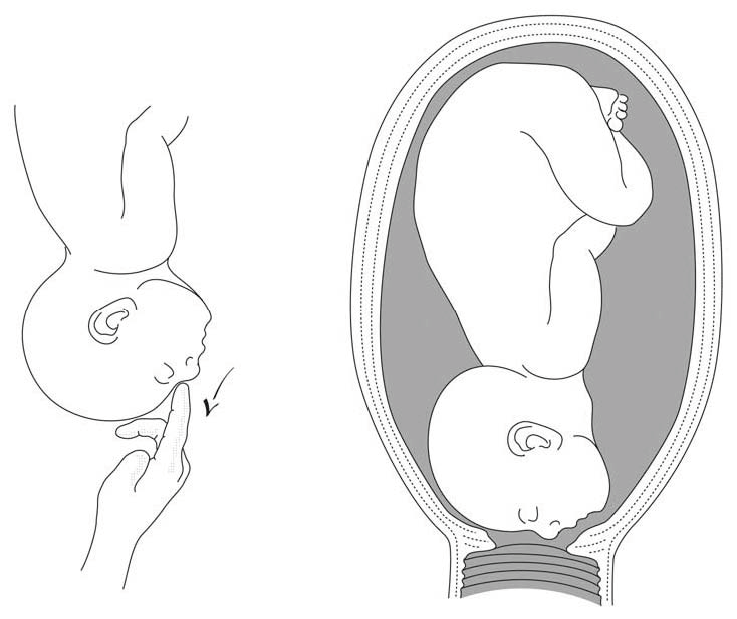

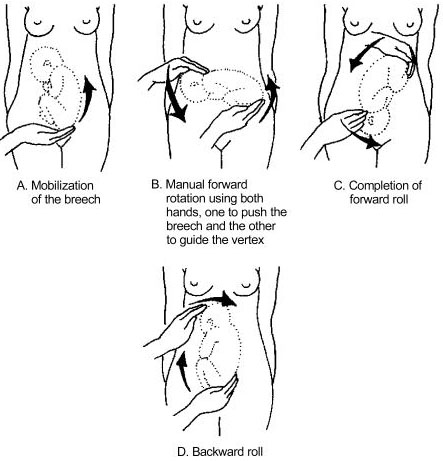

- Convert the brow presentation to a face presentation: between contractions, insert the fingers through the cervix and move the head, encouraging extension (Figures 7.10).

- Attempt internal podalic version ( Section 7.9 ).

Both these manoeuvres pose a significant risk of uterine rupture. Vacuum extraction, forceps and symphysiotomy are contra-indicated.

Foetus dead

Perform an embryotomy if the cervix is sufficiently dilated (Chapter 9, Section 9.7 ) otherwise, a caesarean section.

Face and Brow Presentation

- Author: Teresa Marino, MD; Chief Editor: Carl V Smith, MD more...

- Sections Face and Brow Presentation

- Mechanism of Labor

- Labor Management

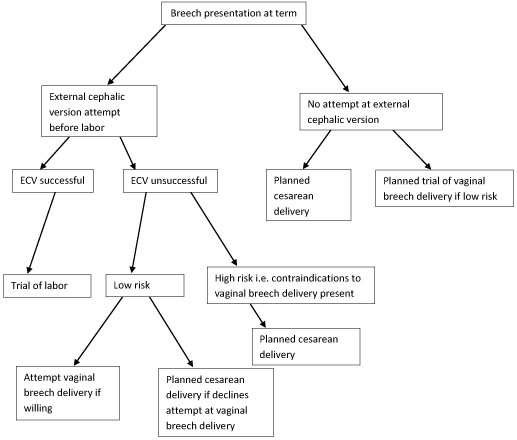

At the onset of labor, assessment of the fetal presentation with respect to the maternal birth canal is critical to the route of delivery. At term, the vast majority of fetuses present in the vertex presentation, where the fetal head is flexed so that the chin is in contact with the fetal thorax. The fetal spine typically lies along the longitudinal axis of the uterus. Nonvertex presentations (including breech, transverse lie, face, brow, and compound presentations) occur in less than 4% of fetuses at term. Malpresentation of the vertex presentation occurs if there is deflexion or extension of the fetal head leading to brow or face presentation, respectively.

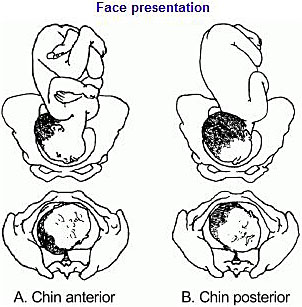

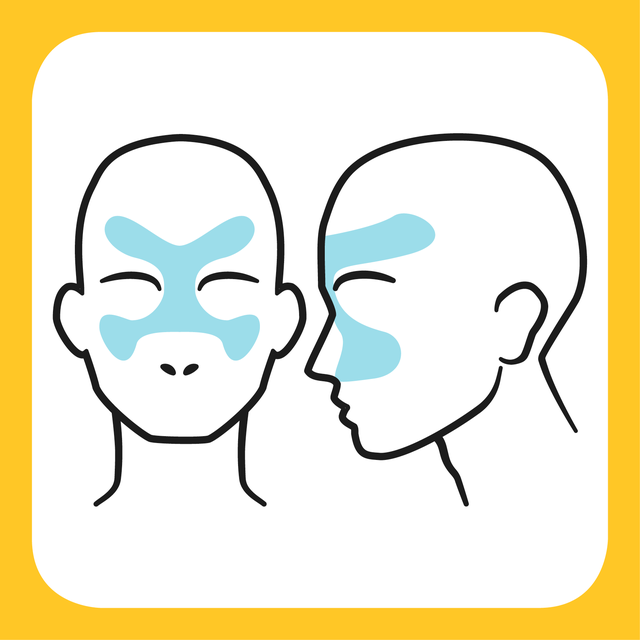

In a face presentation, the fetal head and neck are hyperextended, causing the occiput to come in contact with the upper back of the fetus while lying in a longitudinal axis. The presenting portion of the fetus is the fetal face between the orbital ridges and the chin. The fetal chin (mentum) is the point designated for reference during an internal examination through the cervix. The occiput of a vertex is usually hard and has a smooth contour, while the face and brow tend to be more irregular and soft. Like the occiput, the mentum can present in any position relative to the maternal pelvis. For example, if the mentum presents in the left anterior quadrant of the maternal pelvis, it is designated as left mentum anterior (LMA).

In a brow presentation, the fetal head is midway between full flexion (vertex) and hyperextension (face) along a longitudinal axis. The presenting portion of the fetal head is between the orbital ridge and the anterior fontanel. The face and chin are not included. The frontal bones are the point of designation and can present (as with the occiput during a vertex delivery) in any position relative to the maternal pelvis. When the sagittal suture is transverse to the pelvic axis and the anterior fontanel is on the right maternal side, the fetus would be in the right frontotransverse position (RFT).

Face presentation occurs in 1 of every 600-800 live births, averaging about 0.2% of live births. Causative factors associated with a face presentation are similar to those leading to general malpresentation and those that prevent head flexion or favor extension. Possible etiology includes multiple gestations, grand multiparity, fetal malformations, prematurity, and cephalopelvic disproportion. At least one etiological factor may be identified in up to 90% of cases with face presentation.

Fetal anomalies such as hydrocephalus, anencephaly, and neck masses are common risk factors and may account for as many as 60% of cases of face presentation. For example, anencephaly is found in more than 30% of cases of face presentation. Fetal thyromegaly and neck masses also lead to extension of the fetal head.

A contracted pelvis or cephalopelvic disproportion, from either a small pelvis or a large fetus, occurs in 10-40% of cases. Multiparity or a large abdomen can cause decreased uterine tone, leading to natural extension of the fetal head.

Face presentation is diagnosed late in the first or second stage of labor by examination of a dilated cervix. On digital examination, the distinctive facial features of the nose, mouth, and chin, the malar bones, and particularly the orbital ridges can be palpated. This presentation can be confused with a breech presentation because the mouth may be confused with the anus and the malar bones or orbital ridges may be confused with the ischial tuberosities. The facial presentation has a triangular configuration of the mouth to the orbital ridges compared to the breech presentation of the anus and fetal genitalia. During Leopold maneuvers, diagnosis is very unlikely. Diagnosis can be confirmed by ultrasound evaluation, which reveals a hyperextended fetal neck. [ 1 , 2 ]

Brow presentation is the least common of all fetal presentations and the incidence varies from 1 in 500 deliveries to 1 in 1400 deliveries. Brow presentation may be encountered early in labor but is usually a transitional state and converts to a vertex presentation after the fetal neck flexes. Occasionally, further extension may occur resulting in a face presentation.

The causes of a persistent brow presentation are generally similar to those causing a face presentation and include cephalopelvic disproportion or pelvic contracture, increasing parity and prematurity. These are implicated in more than 60% of cases of persistent brow presentation. Premature rupture of membranes may precede brow presentation in as many as 27% of cases.

Diagnosis of a brow presentation can occasionally be made with abdominal palpation by Leopold maneuvers. A prominent occipital prominence is encountered along the fetal back, and the fetal chin is also palpable; however, the diagnosis of a brow presentation is usually confirmed by examination of a dilated cervix. The orbital ridge, eyes, nose, forehead, and anterior fontanelle are palpated. The mouth and chin are not palpable, thus excluding face presentation. Fetal ultrasound evaluation again notes a hyperextended neck.

As with face presentation, diagnosis is often made late in labor with half of cases occurring in the second stage of labor. The most common position is the mentum anterior, which occurs about twice as often as either transverse or posterior positions. A higher cesarean delivery rate occurs with a mentum transverse or posterior [ 3 ] position than with a mentum anterior position.

The mechanism of labor consists of the cardinal movements of engagement, descent, flexion, internal rotation, and the accessory movements of extension and external rotation. Intuitively, the cardinal movements of labor for a face presentation are not completely identical to those of a vertex presentation.

While descending into the pelvis, the natural contractile forces combined with the maternal pelvic architecture allow the fetal head to either flex or extend. In the vertex presentation, the vertex is flexed such that the chin rests on the fetal chest, allowing the suboccipitobregmatic diameter of approximately 9.5 cm to be the widest diameter through the maternal pelvis. This is the smallest of the diameters to negotiate the maternal pelvis. Following engagement in the face presentation, descent is made. The widest diameter of the fetal head negotiating the pelvis is the trachelobregmatic or submentobregmatic diameter, which is 10.2 cm (0.7 cm larger than the suboccipitobregmatic diameter). Because of this increased diameter, engagement does not occur until the face is at +2 station.

Fetuses with face presentation may initially begin labor in the brow position. Using x-ray pelvimetry in a series of 7 patients, Borrell and Ferstrom demonstrated that internal rotation occurs between the ischial spines and the ischial tuberosities, making the chin the presenting part, lower than in the vertex presentation. [ 4 , 5 ] Following internal rotation, the mentum is below the maternal symphysis, and delivery occurs by flexion of the fetal neck. As the face descends onto the perineum, the anterior fetal chin passes under the symphysis and flexion of the head occurs, making delivery possible with maternal expulsive forces.

The above mechanisms of labor in the term infant can occur only if the mentum is anterior and at term, only the mentum anterior face presentation is likely to deliver vaginally. If the mentum is posterior or transverse, the fetal neck is too short to span the length of the maternal sacrum and is already at the point of maximal extension. The head cannot deliver as it cannot extend any further through the symphysis and cesarean delivery is the safest route of delivery.

Fortunately, the mentum is anterior in over 60% of cases of face presentation, transverse in 10-12% of cases, and posterior only 20-25% of the time. Fetuses with the mentum transverse position usually rotate to the mentum anterior position, and 25-33% of fetuses with mentum posterior position rotate to a mentum anterior position. When the mentum is posterior, the neck, head and shoulders must enter the pelvis simultaneously, resulting in a diameter too large for the maternal pelvis to accommodate unless in the very preterm or small infant.

Three labor courses are possible when the fetal head engages in a brow presentation. The brow may convert to a vertex presentation, to a face presentation, or remain as a persistent brow presentation. More than 50% of brow presentations will convert to vertex or face presentation and labor courses are managed accordingly when spontaneous conversion occurs.

In the brow presentation, the occipitomental diameter, which is the largest diameter of the fetal head, is the presenting portion. Descent and internal rotation occur only with an adequate pelvis and if the face can fit under the pubic arch. While the head descends, it becomes wedged into the hollow of the sacrum. Downward pressure from uterine contractions and maternal expulsive forces may cause the mentum to extend anteriorly and low to present at the perineum as a mentum anterior face presentation.

If internal rotation does not occur, the occipitomental diameter, which measures 1.5 cm wider than the suboccipitobregmatic diameter and is thus the largest diameter of the fetal head, presents at the pelvic inlet. The head may engage but can descend only with significant molding. This molding and subsequent caput succedaneum over the forehead can become so extensive that identification of the brow by palpation is impossible late in labor. This may result in a missed diagnosis in a patient who presents later in active labor.

If the mentum is anterior and the forces of labor are directed toward the fetal occiput, flexing the head and pivoting the face under the pubic arch, there is conversion to a vertex occiput posterior position. If the occiput lies against the sacrum and the forces of labor are directed against the fetal mentum, the neck may extend further, leading to a face presentation.

The persistent brow presentation with subsequent delivery only occurs in cases of a large pelvis and/or a small infant. Women with gynecoid pelvis or multiparity may be given the option to labor; however, dysfunctional labor and cephalopelvic disproportion are more likely if this presentation persists.

Labor management of face and brow presentation requires close observation of labor progression because cephalopelvic disproportion, dysfunctional labor, and prolonged labor are much more common. As mentioned above, the trachelobregmatic or submentobregmatic diameters are larger than the suboccipitobregmatic diameter. Duration of labor with a face presentation is generally the same as duration of labor with a vertex presentation, although a prolonged labor may occur. As long as maternal or fetal compromise is not evident, labor with a face presentation may continue. [ 6 ] A persistent mentum posterior presentation is an indication for delivery by cesarean section.

Continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring is considered mandatory by many authors because of the increased incidence of abnormal fetal heart rate patterns and/or nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns. [ 7 ] An internal fetal scalp electrode may be used, but very careful application of the electrode must be ensured. The mentum is the recommended site of application. Facial edema is common and can obscure the fetal facial anatomy and improper placement can lead to facial and ophthalmic injuries. Oxytocin can be used to augment labor using the same precautions as in a vertex presentation and the same criteria of assessment of uterine activity, adequacy of the pelvis, and reassuring fetal heart tracing.

Fetuses with face presentation can be delivered vaginally with overall success rates of 60-70%, while more than 20% of fetuses with face presentation require cesarean delivery. Cesarean delivery is performed for the usual obstetrical indications, including arrest of labor and nonreassuring fetal heart rate pattern.

Attempts to manually convert the face to vertex (Thom maneuver) or to rotate a posterior position to a more favorable anterior mentum position are rarely successful and are associated with high fetal morbidity and mortality and maternal morbidity, including cord prolapse, uterine rupture, and fetal cervical spine injury with neurological impairment. Given the availability and safety of cesarean delivery, internal rotation maneuvers are no longer justified unless cesarean section cannot be readily performed.

Internal podalic version and breech extraction are also no longer recommended in the modern management of the face presentation. [ 8 ]

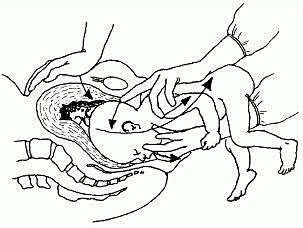

Operative delivery with forceps must be approached with caution. Since engagement occurs when the face is at +2 position, forceps should only be applied to the face that has caused the perineum to bulge. Increased complications to both mother and fetus can occur [ 9 ] and operative delivery must be approached with caution or reserved when cesarean section is not readily available. Forceps may be used if the mentum is anterior. Although the landmarks are different, the application of any forceps is made as if the fetus were presenting directly in the occiput anterior position. The mouth substitutes for the posterior fontanelle, and the mentum substitutes for the occiput. Traction should be downward to maintain extension until the mentum passes under the symphysis, and then gradually elevated to allow the head to deliver by flexion. During delivery, hyperextension of the fetal head should be avoided.

As previously mentioned, the persistent brow presentation has a poor prognosis for vaginal delivery unless the fetus is small, premature, or the maternal pelvis is large. Expectant management is reasonable if labor is progressing well and the fetal well-being is assessed, as there can be spontaneous conversion to face or vertex presentation. The earlier in labor that brow presentation is diagnosed, the higher the likelihood of conversion. Minimal intervention during labor is recommended and some feel the use of oxytocin in the brow presentation is contraindicated.

The use of operative vaginal delivery or manual conversion of a brow to a more favorable presentation is contraindicated as the risks of perinatal morbidity and mortality are unacceptably high. Prolonged, dysfunctional, and arrest of labor are common, necessitating cesarean section delivery.

The incidence of perinatal morbidity and mortality and maternal morbidity has decreased due to the increased incidence of cesarean section delivery for malpresentation, including face and brow presentation.

Neonates delivered in the face presentation exhibit significant facial and skull edema, which usually resolves within 24-48 hours. Trauma during labor may cause tracheal and laryngeal edema immediately after delivery, which can result in neonatal respiratory distress. In addition, fetal anomalies or tumors, such as fetal goiters that may have contributed to fetal malpresentation, may make intubation difficult. Physicians with expertise in neonatal resuscitation should be present at delivery in the event that intubation is required. When a fetal anomaly has been previously diagnosed by ultrasonographic evaluation, the appropriate pediatric specialists should be consulted and informed at time of labor.

Bellussi F, Ghi T, Youssef A, et al. The use of intrapartum ultrasound to diagnose malpositions and cephalic malpresentations. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2017 Dec. 217 (6):633-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

[Guideline] Ghi T, Eggebø T, Lees C, et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: intrapartum ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol . 2018 Jul. 52 (1):128-39. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] . [Full Text] .

Shaffer BL, Cheng YW, Vargas JE, Laros RK Jr, Caughey AB. Face presentation: predictors and delivery route. Am J Obstet Gynecol . 2006 May. 194(5):e10-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Borell U, Fernstrom I. The mechanism of labour. Radiol Clin North Am . 1967 Apr. 5(1):73-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Borell U, Fernstrom I. The mechanism of labour in face and brow presentation: a radiographic study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand . 1960. 39:626-44.

Gardberg M, Leonova Y, Laakkonen E. Malpresentations--impact on mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand . 2011 May. 90(5):540-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Collaris RJ, Oei SG. External cephalic version: a safe procedure? A systematic review of version-related risks. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand . 2004 Jun. 83(6):511-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Verspyck E, Bisson V, Gromez A, Resch B, Diguet A, Marpeau L. Prophylactic attempt at manual rotation in brow presentation at full dilatation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand . 2012 Nov. 91(11):1342-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Johnson JH, Figueroa R, Garry D. Immediate maternal and neonatal effects of forceps and vacuum-assisted deliveries. Obstet Gynecol . 2004 Mar. 103(3):513-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Benedetti TJ, Lowensohn RI, Truscott AM. Face presentation at term. Obstet Gynecol . 1980 Feb. 55(2):199-202. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

BROWNE AD, CARNEY D. OBSTETRICS IN GENERAL PRACTICE. MANAGEMENT OF MALPRESENTATIONS IN OBSTETRICS. Br Med J . 1964 May 16. 1(5393):1295-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Campbell JM. Face presentation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol . 1965 Nov. 5(4):231-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link] .

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Teresa Marino, MD Assistant Professor, Attending Physician, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Tufts Medical Center Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Carl V Smith, MD The Distinguished Chris J and Marie A Olson Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Senior Associate Dean for Clinical Affairs, University of Nebraska Medical Center Carl V Smith, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists , American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine , Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics , Central Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists , Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine , Council of University Chairs of Obstetrics and Gynecology , Nebraska Medical Association Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chitra M Iyer, MD, Perinatologist, Obstetrix Medical Group, Fort Worth, Texas.

Chitra M Iyer, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists , Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine .

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

What would you like to print?

- Print this section

- Print the entire contents of

- Print the entire contents of article

- HIV in Pregnancy

- Pulmonary Disease and Pregnancy

- Kidney Disease and Pregnancy

- Vaccinations/Immunizations During Pregnancy

- Anemia and Thrombocytopenia in Pregnancy

- Common Pregnancy Complaints and Questions

- Adrenal Disease and Pregnancy

- Is immunotherapy for cancer safe in pregnancy?

- Labetalol, Nifedipine: Outcome on Pregnancy Hypertension

- Olympic Moms Are Redefining Exercise in Pregnancy

- Drug Interaction Checker

- Pill Identifier

- Calculators

- 2020/viewarticle/immunotherapy-cancer-safe-pregnancy-2024a100083dnews news Is immunotherapy for cancer safe in pregnancy?

- 2002261369-overviewDiseases & Conditions Diseases & Conditions Postterm Pregnancy

- 2001/viewarticle/labetalol-nifedipine-outcome-pregnancy-hypertension-2024a1000capnews news Labetalol, Nifedipine: Outcome on Pregnancy Hypertension

- 2022 New Pearls of Exxcellence Articles

Management of Brow, Face, and Compound Malpresentations

Author: Meera Kesavan, MD

Mentor: Lisa Keder MD Editor: Daniel JS Martingano DO MBA PhD

Registered users can also download a PDF or listen to a podcast of this Pearl. Log in now , or create a free account to access bonus Pearls features.

Fetal malpresentation, including brow, face, or compound presentations, complicates around 3-4% of all term births. Because these abnormal fetal presentations still are cephalic, many such cases result in vaginal deliveries, yet there are increased risks for adverse outcomes, including cesarean delivery resultant surgical complications, persistent malpresentation precluding vaginal delivery, and abnormal labor resulting in arrest of dilation or descent.

These fetal malpresentation are differentiated in the following ways:

- In face presentations, the presenting part is the mentum, which is further divided based on its position, including mentum posterior, mentum transverse or mentum anterior positions. This typically occurs because of hyperextension of the neck and the occiput touching the fetal back. Mentum anterior malpresentations can potentially achieve vaginal deliveries, whereas mentum posterior malpresentations cannot.

- In brow presentations, there is less extension of the fetal neck as in face presentations making the leading fetal part being the area between the anterior fontanelle and the orbital ridges. These presentations are uncommon and are managed similarly to face presentations. Brow presentation can be further described based on the position of the anterior fontanelle as frontal anterior, posterior, or transverse.

- Compound presentation is defined as the leading fetal part, including a fetal extremity, alongside a cephalic or breech presentation. Management of compound presentations is expected (and often incidentally noted following delivery) because the extremity will often either retract as the head descends or will feasibly allow for delivery in its current position, with manipulation attempts to reduce the compound presentation usually avoided.

Risk factors for brow and face presentations include fetal CNS malformations, congenital or chromosomal anomalies, advanced maternal age, low birthweight, abnormal maternal pelvic anatomy (e.g. contracted pelvis, cephalopelvic disporotion, platypelloid pelvis, etc.) and nulliparity. non-Hispanic White women have the highest risk for malpresentation, whereas non-Hispanic Black women have the lowest risk.

Diagnosis usually is made during the second stage of labor while performing routine vaingla examinations and involves palpation of the abnormal leading fetal part (forehead, orbital ridge, orbits, nose, etc.) Obstetric ultrasound can additionally provide complimentary information to support these diagnoses and distinguish from other fetal malpresentations or malpositions. In face presentation, the mentum (chin) and mouth are palpable.

Management considerations for face, brow, and compounds presentations are unique with compound presentations having higher rates of vaginal delivery and lower complications as compared to either brow or face presentations.

- For brow presentations, approximately 30-40% of brow presentations will convert to a face presentation, and about 20% will convert to a vertex presentation. Anterior positions have the possibility of vaginal deliveries and can be managed by usual labor management principles, whereas mentum posterior positions are indications for cesarean delivery.

- For face presentations, the likelihood of vaginal delivery depends on the orientation of the mentum, with mentum anterior being most suitable for vaginal delivery. If the fetus is mentum posterior, flexion of the neck is precluded and results in the inability of fetal descent.

- For compound presentations, management is expectant and manipulation of the leading extremities should be avoided. Most cases of compound presentation result in vaginal deliveries. For term deliveries, compound presentations with parts other than the hand are unlikely to result in safe vaginal delivery.

Labor management for brow and face presentation overall involves continuous fetal heart rate monitoring and repeat clinical assessments, given the increased potential of fetal complications as noted. Caution should be used with internal monitoring devices, which can cause ophthalmic injury or trauma to the presenting fetal parts, with the use of fetal scalp electrodes discouraged and intrauterine pressure catheters acceptable with appropriate clinical judgment and feasibility.

Midforceps, breech extraction, and manual manipulation are not recommended and increase the risk of maternal and neonatal morbidity.

Neonatal outcomes for both face and brow presentations include facial edema, bruising, and soft tissue trauma. Complications of compound presentation specifically include umbilical cord prolapse and injury to the presenting limb. With appropriate management, neonatal and maternal morbidity for face, brow, and compound presentations are low.

Further Reading:

Bar-El L, Eliner Y, Grunebaum A, Lenchner E, et al. Race and ethnicity are among the predisposing factors for fetal malpresentation at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021 Sep;3(5):100405. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100405. Epub 2021 Jun 4. PMID: 34091061.

Bellussi F, Ghi T, Youssef A, et al. The use of intrapartum ultrasound to diagnose malpositions and cephalic malpresentations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Dec;217(6):633-641. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.07.025. Epub 2017 Jul 22. PMID: 28743440 .

Pilliod RA, Caughey AB. Fetal Malpresentation and Malposition: Diagnosis and Management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017 Dec;44(4):631-643. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.08.003. PMID: 29078945 .

Zayed F, Amarin Z, Obeidat B, et al. Face and brow presentation in northern Jordan, over a decade of experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008 Nov;278(5):427-30. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0600-0. Epub 2008 Feb 19. PMID: 18283473 .

Initial Approval: August 2013; Revised: 11/2016; Revised July 2018; Reaffirmed January 2020; Revised September 2021. Revised July 2023.

This site uses cookies.

This feature is only available for registered users.

Log in here:, not a registered user.

Becoming a registered user gives you access to special features like PDF downloads and podcast episodes of each SASGOG Pearl of Exxcellence.

Create a Free Account

Are you sure you want to remove this Pearl from your favorites list?

- Getting pregnant

- Preschooler

- Life as a parent

- Baby essentials

- Find your birth club

- Free antenatal classes

- Meet local parents & parents-to-be

- See all in Community

- Ovulation calculator

- Am I pregnant quiz

- How to get pregnant fast

- Best sex positions

- Signs of pregnancy

- How many days after your period can you get pregnant?

- How age affects fertility

- Very early signs of pregnancy

- What fertile cervical mucus looks like

- Think you're pregnant but the test is negative?

- Faint line on pregnancy test

- See all in Getting pregnant

- Pregnancy week by week

- How big is my baby?

- Due date calculator

- Baby movements week by week

- Symptoms you should never ignore

- Hospital bag checklist

- Signs of labour

- Your baby's position in the womb

- Baby gender predictor

- Vaginal spotting

- Fetal development chart

- See all in Pregnancy

- Baby names finder

- Baby name inspiration

- Popular baby names 2022

- Numerology calculator

- Gender-neutral names

- Old-fashioned names

- See all in Baby names

- Your baby week by week

- Baby milestones by month

- Baby rash types

- Baby poop chart

- Ways to soothe a crying baby

- Safe co-sleeping

- Teething signs

- Growth spurts

- See all in Baby

- Your toddler month by month

- Toddler development milestones

- Dealing with tantrums

- Toddler meals

- Food & fussy eating

- When to start potty training

- Moving from a cot to a bed

- Help your child sleep through

- Games & activities

- Vomiting: what's normal?

- See all in Toddler

- Your child month by month

- Food ideas & nutrition

- How kids learn to share

- Coping with aggression

- Bedtime battles

- Anxiety in children

- Dealing with public tantrums

- Great play ideas

- Is your child ready for school?Top tips for starting school

- See all in Preschooler

- Postnatal symptoms to watch out for

- Stitches after birth

- Postpartum blood clots

- Baby showers

- Sex secrets for parents

- See all in Life as a parent

- Best baby products

- Best formula and bottles for a windy baby

- Best car seats if you need three to fit

- Best nappies

- Best Moses baskets

- Best baby registries

- Best baby sleeping bags

- Best baby humidifier

- Best baby monitors

- Best baby bath seat

- Best baby food

- See all in Baby essentials

- Back pain in pregnancy

- Pelvic girdle pain

- Perineal massage

- Signs you're having a boy

- Signs you're having a girl

- Can you take fish oil while pregnant?

- 18 weeks pregnant bump

- Can you eat salami when pregnant?

- Edwards' syndrome

- Missed miscarriage

- Should I harvest my colostrum?

- Rhesus positive vs. Rhesus negative

- What do contractions feel like?

- Hunger in early pregnancy

- First poop after birth

- When do babies sit up?

- When can babies have salt?

- MMR vaccine rash

- Vaping while breastfeeding

- How to transition from formula to milk

- When do babies start grabbing things?

- Sperm allergy: can sperm cause itching?

- How long after taking folic acid can I get pregnant?

What is brow presentation?

- the size or shape of your pelvis

- because your baby is premature

- an abnormality that prevents your baby from tucking in her chin

- having too much amniotic fluid ( polyhydramnios )

Was this article helpful?

Forceps and ventouse (assisted birth)

Parents' tips: what to do if your mum wants to be at your baby's birth

How can I use breathing exercise during labour? (Video)

Dads' guide to pregnancy: one month

Where to go next

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed, delivery, face and brow presentation, affiliations.

- 1 Vilnius University, Lithuania, Imperial London Healthcare NHS Trust

- 2 University of Health Sciences, Rawalpindi Medical College

- PMID: 33620804

- Bookshelf ID: NBK567727

The term presentation describes the leading part of the fetus or the anatomical structure closest to the maternal pelvic inlet during labor. The presentation can roughly be divided into the following classifications: cephalic, breech, shoulder, and compound. Cephalic presentation is the most common and can be further subclassified as vertex, sinciput, brow, face, and chin. The most common presentation in term labor is the vertex, where the fetal neck is flexed to the chin, minimizing the head circumference.

Face presentation – an abnormal form of cephalic presentation where the presenting part is mentum. This typically occurs because of hyperextension of the neck and the occiput touching the fetal back. Incidence of face presentation is rare, accounting for approximately 1 in 600 of all presentations.

In brow presentation, the neck is not extended as much as in face presentation, and the leading part is the area between the anterior fontanelle and the orbital ridges. Brow presentation is considered the rarest of all malpresentation with a prevalence of 1 in 500 to 1 in 4000 deliveries.

Both face and brow presentations occur due to extension of the fetal neck instead of flexion; therefore, conditions that would lead to hyperextension or prevent flexion of the fetal neck can all contribute to face or brow presentation. These risk factors may be related to either the mother or the fetus. Maternal risk factors are preterm delivery, contracted maternal pelvis, platypelloid pelvis, multiparity, previous cesarean section, black race. Fetal risk factors include anencephaly, multiple loops of cord around the neck, masses of the neck, macrosomia, polyhydramnios.

These malpresentations are usually diagnosed during the second stage of labor when performing a digital examination. It is possible to palpate orbital ridges, nose, malar eminences, mentum, mouth, gums, and chin in face presentation. Based on the position of the chin, face presentation can be further divided into mentum anterior, posterior, or transverse. In brow presentation, anterior fontanelle and face can be palpated except for the mouth and the chin. Brow presentation can then be further described based on the position of the anterior fontanelle as frontal anterior, posterior, or transverse.

Diagnosing the exact presentation can be challenging, and face presentation may be misdiagnosed as frank breech. To avoid any confusion, a bedside ultrasound scan can be performed. The ultrasound imaging can show a reduced angle between the occiput and the spine or, the chin is separated from the chest. However, ultrasound does not provide much predicting value in the outcome of the labor.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Disclosure: Julija Makajeva declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Mohsina Ashraf declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

- Continuing Education Activity

- Introduction

- Anatomy and Physiology

- Indications

- Contraindications

- Preparation

- Technique or Treatment

- Complications

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Similar articles

- Sonographic diagnosis of fetal head deflexion and the risk of cesarean delivery. Bellussi F, Livi A, Cataneo I, Salsi G, Lenzi J, Pilu G. Bellussi F, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Nov;2(4):100217. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100217. Epub 2020 Aug 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020. PMID: 33345926

- Sonographic evaluation of the fetal head position and attitude during labor. Ghi T, Dall'Asta A. Ghi T, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024 Mar;230(3S):S890-S900. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.003. Epub 2023 May 19. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024. PMID: 37278991 Review.

- Leopold Maneuvers. Superville SS, Siccardi MA. Superville SS, et al. 2023 Feb 19. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. 2023 Feb 19. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 32809649 Free Books & Documents.

- Intrapartum sonographic assessment of the fetal head flexion in protracted active phase of labor and association with labor outcome: a multicenter, prospective study. Dall'Asta A, Rizzo G, Masturzo B, Di Pasquo E, Schera GBL, Morganelli G, Ramirez Zegarra R, Maqina P, Mappa I, Parpinel G, Attini R, Roletti E, Menato G, Frusca T, Ghi T. Dall'Asta A, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Aug;225(2):171.e1-171.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.02.035. Epub 2021 Mar 4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021. PMID: 33675795

- Labor with abnormal presentation and position. Stitely ML, Gherman RB. Stitely ML, et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2005 Jun;32(2):165-79. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2004.12.005. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2005. PMID: 15899353 Review.

- Gardberg M, Leonova Y, Laakkonen E. Malpresentations--impact on mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011 May;90(5):540-2. - PubMed

- Tapisiz OL, Aytan H, Altinbas SK, Arman F, Tuncay G, Besli M, Mollamahmutoglu L, Danışman N. Face presentation at term: a forgotten issue. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014 Jun;40(6):1573-7. - PubMed

- Zayed F, Amarin Z, Obeidat B, Obeidat N, Alchalabi H, Lataifeh I. Face and brow presentation in northern Jordan, over a decade of experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008 Nov;278(5):427-30. - PubMed

- Bashiri A, Burstein E, Bar-David J, Levy A, Mazor M. Face and brow presentation: independent risk factors. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008 Jun;21(6):357-60. - PubMed

- Shaffer BL, Cheng YW, Vargas JE, Laros RK, Caughey AB. Face presentation: predictors and delivery route. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 May;194(5):e10-2. - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in PubMed

- Search in MeSH

- Add to Search

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- NCBI Bookshelf

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Brow Presentation

- First Online: 02 August 2023

Cite this chapter

- Syeda Batool Mazhar 2 &

- Zahra Ahmed Muslim 2

584 Accesses

Brow presentation is the rarest of all malpresentations. Anencephaly, neck masses in fetus, polyhydramnios, multiple loops of cord around neck are the fetal factors leading to brow presentation. Contracted pelvis, preterm labour, platypelloid pelvis are some of the contributory maternal factors for brow presentation. Diagnosis is usually made during second stage of labour during prevaginal examination when anterior frontanelle and face are palpated. Cesarean section is performed in brow presentation as it is unusual to get conversion in average sized fetus once membranes have ruptured.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Arulkumaran S, Robson M, editors. Munro Kerr operative obstetrics. 13th ed. Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2019. p. 89–93.

Google Scholar

Malvasi A, Barbera A, Di Vagno G, Gimovsky A, Berghella V, Ghi T, Di Renzo GC, Tinelli A. Asynclitism: a literature review of an often forgotten clinical condition. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(16):1890–4. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2014.972925 . Epub 2014 Oct 29.PMID: 25283847.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bellussi F, Ghi T, Youssef A, Salsi G, Giorgetta F, Parma D, Simonazzi G, Gianluigi P. The use of intrapartum ultrasound to diagnose malpositions and cephalic malpresentations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(6):633–41.

Lanni SM, Gherman R, Gonik B. Malpresentations. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017.

Book Google Scholar

Bashiri A, Burstein E, Bar-David J, et al. Face and brow presentation: independent risk factors. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(6):357–60.

Hawkins JL, Koffel BL. Chapter 35. In: Chestnut’s obstetric anesthesia: principles and practice: abnormal presentation & multiple gestation. 6th ed; 2020. p. 830.

Meltzer RM, Sactleben MR, Friedman EA. Brow presentation. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1968;23(6):255–63.

Article Google Scholar

Borell U, Fernstrom I. The mechanism of labour in face and brow presentation: a radiological study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1960;39:626–44.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Levy DL. Persistent brow presentation: a new approach to management. South Med J. 1976;69(2):191–2.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

MCH Centre, PIMS, Islamabad, Pakistan

Syeda Batool Mazhar & Zahra Ahmed Muslim

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sarojini Naidu Medical College, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India

Ruchika Garg

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Mazhar, S.B., Muslim, Z.A. (2023). Brow Presentation. In: Garg, R. (eds) Labour and Delivery. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6145-8_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6145-8_8

Published : 02 August 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-6144-1

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-6145-8

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What Is Brow Presentation? What Are Its Complications?

What Is Brow Presentation?

What leads to brow presentation, diagnosis of brow presentation, how to avoid c-section if baby is in brow presentation, what complications can arise due to brow presentation.

Unlike the flexed position, in a brow presentation, the baby’s head will not be well flexed into its chest. Therefore, her head and neck will be extended back a little, as if it is looking up. If the baby remains in a brow presentation, it is doubtful that there will be enough space for the baby to descend through the pelvis. This increases the chances of a C-section . Brow presentation is least common of all fetal presentations. In fact, it happens one in every 1400 deliveries. Over half of the babies who are in brow presentation in the early labor will flex their head down during the pushing stage of the labor and the labor may progress as expected. Out of the other 50%, some babies tend to tip their head further back to the face first position while they descends further into the birth canal. Compared to the brow presentation, face first position has a higher chance to undergo a vaginal birth, provided, the chin of the baby is near the pubic bone. But if the baby’s chin is near the tailbone, C-section is the only option to avoid any complications in the delivery. In spite of the fact that brow presentation very rarely happens, it can happen to anybody. If the baby stays in a brow presentation, it is highly unlikely that there will be enough room for it to pass through the pelvis. If the labor is not progressing, or that the baby is becoming distressed, then the doctor will recommend a caesarean delivery.

There are several conditions, which increase the chances of brow presentation. The brow presentation usually takes place because of :

- Polyhydramnios : Excess amniotic fluid can make it difficult for the baby’s head to take a flexed position

- Size and shape of the pelvis: Abnormally shaped and sized pelvis can make it difficult for the baby to pick up a vertex presentation. Android pelvis, which has a triangular or heart-shaped inlet with a narrower front part, is usually behind most of the brow presentations. Similarly, contracted pelvis, a pelvis that is abnormally small, can cause brow presentation

- Fetal abnormality: Fetal abnormalities such as hydrocephalus, anencephaly and neck masses accounts for the majority of brow presentations

- Premature birth/low birth weight baby: If the baby is born prematurely or if the baby is having low birth weight , the chances of brow presentation increases

- Big baby : If the baby is larger than normal size, the baby tends to extend its head instead of curling inward

- Multiple pregnancies: Multiple pregnancies also increase the risk of brow presentation

- Multiple nuchal cords: If the umbilical cord wraps around the baby’s neck, obviously, it cannot tuck its chin into the chest. In such cases, the baby tends to be brow or face presentations

- Laxity of the uterus: If the uterine wall loses its firmness, the baby may not able to hold its chin tucked to the chest firmly and the baby tends to be in brow presentation

- Cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD): If the mother’s pelvis and the baby’s head are not proportionate to each other, brow presentation can happen

When the baby is in brow presentation, the labor will not progress as it should and prolonged labor can result in fetal distress, calling for an immediate C-section. However, if the baby picks up brow presentation and your cervix is fully dilated, there are two procedures through which the doctors try to avoid the need of C-section.

- Manual rotation: Doctor inserts his hand through the cervix and tries to flex the baby’s head

- The baby’s head should be engaged in the pelvis and should be in a front anterior position

- The pelvis should have sufficient room to permit the ventouse cup to be inserted posteriorly and to reach the occiput

- Ability and experience of the obstetrician

- How favorable is the position of the baby’s head inside the pelvis

- Available space inside the pelvis

If both these methods fail, then the doctor will go ahead with the decision to perform a caesarean.

There are several complications associated with a brow presentation if vaginal delivery is attempted without proper measures.

- Increased chances of spinal cord injury are associated with brow presentation

- Fetal distress

- Abnormal shape of the baby’s head after delivery

- Prolonged labor

- Increased chances of using forceps which in turn increases the chances of facial trauma

- Obstructed labor

If it is your first delivery, it is very unlikely that your baby will be in a brow presentation. Also if you had a brow presentation in one delivery, it doesn’t mean that it will definitely happen in your next delivery. Once you are closer to your delivery date, make sure you do not miss any of your doctor appointments.It is advisable to follow your doctor’s instructions from the very beginning of your pregnancy. Make sure you take all precautionary measures to avoid any kind of uneasiness. Have a balanced diet and sufficient rest. Keep yourself positive as you get ready for a healthy delivery . Have a safe and happy pregnancy!

With a rich experience in pregnancy and parenting, our team of experts create insightful, well-curated, and easy-to-read content for our to-be-parents and parents at all stages of parenting.

Related Posts

Meaning of advait – origin, popularity and more, meaning of sathvik – origin, popularity and more, tea during pregnancy – safe choices and risks.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

- GP practice services

- Health advice

- Health research

- Medical professionals

Health topics

Advice and clinical information on a wide variety of healthcare topics.

All health topics

Latest features

Allergies, blood & immune system

Bones, joints and muscles

Brain and nerves

Chest and lungs

Children's health

Cosmetic surgery

Digestive health

Ear, nose and throat

General health & lifestyle

Heart health and blood vessels

Kidney & urinary tract

Men's health

Mental health

Oral and dental care

Senior health

Sexual health

Signs and symptoms

Skin, nail and hair health

Travel and vaccinations

Treatment and medication

Women's health

Healthy living

Expert insight and opinion on nutrition, physical and mental health.

Exercise and physical activity

Healthy eating

Healthy relationships

Managing harmful habits

Mental wellbeing

Relaxation and sleep

Managing conditions

From ACE inhibitors for high blood pressure, to steroids for eczema, find out what options are available, how they work and the possible side effects.

Featured conditions

ADHD in children

Crohn's disease

Endometriosis

Fibromyalgia

Gastroenteritis

Irritable bowel syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Scarlet fever

Tonsillitis

Vaginal thrush

Health conditions A-Z

Medicine information

Information and fact sheets for patients and professionals. Find out side effects, medicine names, dosages and uses.

All medicines A-Z

Allergy medicines

Analgesics and pain medication

Anti-inflammatory medicines

Breathing treatment and respiratory care

Cancer treatment and drugs

Contraceptive medicines

Diabetes medicines

ENT and mouth care

Eye care medicine

Gastrointestinal treatment

Genitourinary medicine

Heart disease treatment and prevention

Hormonal imbalance treatment

Hormone deficiency treatment

Immunosuppressive drugs

Infection treatment medicine

Kidney conditions treatments

Muscle, bone and joint pain treatment

Nausea medicine and vomiting treatment

Nervous system drugs

Reproductive health

Skin conditions treatments

Substance abuse treatment

Vaccines and immunisation

Vitamin and mineral supplements

Tests & investigations

Information and guidance about tests and an easy, fast and accurate symptom checker.

About tests & investigations

Symptom checker

Blood tests

BMI calculator

Pregnancy due date calculator

General signs and symptoms

Patient health questionnaire

Generalised anxiety disorder assessment

Medical professional hub

Information and tools written by clinicians for medical professionals, and training resources provided by FourteenFish.

Content for medical professionals

FourteenFish training

- Professional articles

Evidence-based professional reference pages authored by our clinical team for the use of medical professionals.

View all professional articles A-Z

Actinic keratosis

Bronchiolitis

Molluscum contagiosum

Obesity in adults

Osmolality, osmolarity, and fluid homeostasis

Recurrent abdominal pain in children

Medical tools and resources

Clinical tools for medical professional use.

All medical tools and resources

Malpresentations and malpositions

Peer reviewed by Dr Laurence Knott Last updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP Last updated 22 Jun 2021

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- Download Download Article PDF has been downloaded

- Share via email

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find one of our health articles more useful.

In this article :

Malpresentation, malposition.

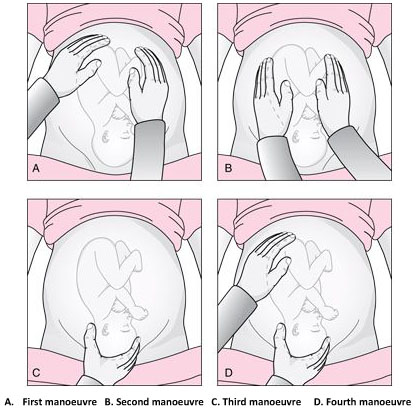

Usually the fetal head engages in the occipito-anterior position (more often left occipito-anterior (LOA) rather than right) and then undergoes a short rotation to be directly occipito-anterior in the mid-cavity. Malpositions are abnormal positions of the vertex of the fetal head relative to the maternal pelvis. Malpresentations are all presentations of the fetus other than vertex.

Obstetrics - the pelvis and head

Continue reading below

Predisposing factors to malpresentation include:

Prematurity.

Multiple pregnancy.

Abnormalities of the uterus - eg, fibroids.

Partial septate uterus.

Abnormal fetus.

Placenta praevia.

Primiparity.

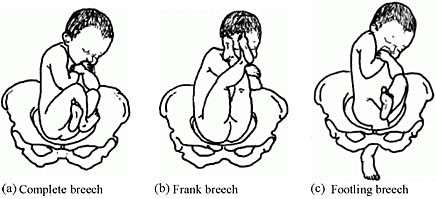

Breech presentation

See the separate Breech Presentations article for more detailed discussion.

Breech presentation is the most common malpresentation, with the majority discovered before labour. Breech presentation is much more common in premature labour.

Approximately one third are diagnosed during labour when the fetus can be directly palpated through the cervix.

After 37 weeks, external cephalic version can be attempted whereby an attempt is made to turn the baby manually by manipulating the pregnant mother's abdomen. This reduces the risk of non-cephalic delivery 1 .

Maternal postural techniques have also been tried but there is insufficient evidence to support these 2 .

Many women who have a breech presentation can deliver vaginally. Factors which make this less likely to be successful include 3 :

Hyperextended neck on ultrasound.

High estimated fetal weight (more than 3.8 kg).

Low estimated weight (less than tenth centile).

Footling presentation.

Evidence of antenatal fetal compromise.

Transverse lie 4

When the fetus is positioned with the head on one side of the pelvis and the buttocks in the other (transverse lie), vaginal delivery is impossible.

This requires caesarean section unless it converts or is converted late in pregnancy. The surgeon may be able to rotate the fetus through the wall of the uterus once the abdominal wall has been opened. Otherwise, a transverse uterine incision is needed to gain access to a fetal pole.

Internal podalic version is no longer attempted.

Transverse lie is associated with a risk of cord prolapse of up to 20%.

Occipito-posterior position

This is the most common malposition where the head initially engages normally but then the occiput rotates posteriorly rather than anteriorly. 5.2% of deliveries are persistent occipito-posterior 5 .

The occipito-posterior position results from a poorly flexed vertex. The anterior fontanelle (four radiating sutures) is felt anteriorly. The posterior fontanelle (three radiating sutures) may also be palpable posteriorly.

It may occur because of a flat sacrum, poorly flexed head or weak uterine contractions which may not push the head down into the pelvis with sufficient strength to produce correct rotation.

As occipito-posterior-position pregnancies often result in a long labour, close maternal and fetal monitoring are required. An epidural is often recommended and it is essential that adequate fluids be given to the mother.

The mother may get the urge to push before full dilatation but this must be discouraged. If the head comes into a face-to-pubis position then vaginal delivery is possible as long as there is a reasonable pelvic size. Otherwise, forceps or caesarean section may be required.

Occipito-transverse position

The head initially engages correctly but fails to rotate and remains in a transverse position.

Alternatives for delivery include manual rotation of fetal head using Kielland's forceps, or delivery using vacuum extraction. This is inappropriate if there is any fetal acidosis because of the risk of cerebral haemorrhage.

Therefore, there must be provision for a failure of forceps delivery to be changed immediately to a caesarean. The trial of forceps is therefore often performed in theatre. Some centres prefer to manage by caesarean section without trial of forceps.

Face presentations

Face presents for delivery if there is complete extension of the fetal head.

Face presentation occurs in 1 in 1,000 deliveries 5 .

With adequate pelvic size, and rotation of the head to the mento-anterior position, vaginal delivery should be achieved after a long labour.

Backwards rotation of the head to a mento-posterior position requires a caesarean section.

Brow positions

The fetal head stays between full extension and full flexion so that the biggest diameter (the mento-vertex) presents.

Brow presentation occurs in 0.14% of deliveries 5 .

Brow presentation is usually only diagnosed once labour is well established.

The anterior fontanelle and super orbital ridges are palpable on vaginal examination.

Unless the head flexes, a vaginal delivery is not possible, and a caesarean section is required.

Further reading and references

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM ; External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 1;(4):CD000083. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R ; Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;10:CD000051. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000051.pub2.

- Management of Breech Presentation ; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Mar 2017)

- Szaboova R, Sankaran S, Harding K, et al ; PLD.23 Management of transverse and unstable lie at term. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014 Jun;99 Suppl 1:A112-3. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306576.324.

- Gardberg M, Leonova Y, Laakkonen E ; Malpresentations - impact on mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011 May;90(5):540-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01105.x.

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 21 Jun 2026

22 jun 2021 | latest version.

Last updated by

Peer reviewed by

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

- Vishal's account

- Complications

Brow Presentation – An Overview

What Is Brow Presentation?

How can you get to know if your baby is in this position, what are the causes of brow presentation, how is the diagnosis made, complications of brow presentation delivery, alternatives for labor during brow presentation, precautions to take before and after labour, how will brow presentation affect your baby during labor.

Pregnancy is a beautiful experience that is also fraught with a host of complications and risks. One of them concerns the normal orientation of your baby inside your uterus, which is essential for a smooth delivery. This article will explain all about abnormal forehead presentation and its associated causes, complications, diagnosis, treatment and precautions.

Babies assume a fixed position in the uterus, that is with their chins tucked firmly into their chests. This position is ideal to exit the uterus smoothly. However, in some cases, the baby’s head and neck will extend backwards away from their chest. This is known as a brow presentation or forehead presentation. It is an extremely rare condition, occurring once in 1500 births. Brow presentation might obstruct vaginal births from occurring as there is less space for the baby to drop down towards the pelvic girdle. However, if brow presentation occurs early in labour, there is still time for them to flex their neck back to the right position. If not, labour might be hindered, causing stress for both, the mother and the baby. In these instances, your doctor might recommend a caesarean section. A brow baby tends to occur in women pregnant for the second or third time, or due to physical defects like an abnormally developed spine.

Brow babies are rarely detected before labor begins, but around half of them will shift to a face-first or crown-first presentation suitable for delivery. A brow presentation delivery will take much longer than normal, which is usually when the condition is discovered.

There are several potential reasons for your baby to assume this orientation. Some of them are:

- Fetal Size: Babies born preterm, or with low birth weights, raise the likelihood of them presenting brow first. This is also observed in large babies, who usually flex their head outwards rather than in towards their chest. Brow presentation can also be caused if your pelvic girdle and your baby’s head are disproportionate to each other.

- Polyhydramnios: Polyhydramnios is the condition in which there is too much amniotic fluid in your uterus. Thus, it might be tricky for your baby to fix their heads in the correct position.

- Multiple Pregnancy: Carrying twins or more in your womb decreases the amount of space available, making your babies take alternative positions to fit properly.

- Maternal Defects: If your pelvis is not the right shape and size, it might be difficult for your fetus to assume normal presentations. The most common cause of brow presentation is the triangle-shaped android pelvis and the atypically small contracted pelvis. Another maternal defect is a lax uterus, which is not firm enough to hold the baby in place, resulting in different presentations.

- Fetal Defects: If your baby has conditions such as anencephaly and hydrocephalus, their abnormally large heads will not be able to take the right position.

To diagnose brow presentation, an experienced doctor will be able to help. Ultrasound scans are compulsory for monitoring the situation. Your doctor might even conduct a digital examination to check the orientation of the baby’s facial features. If they find that the baby’s head does not rotate enough for a natural birth, they might recommend a caesarean section.

Several risks come with brow presentation birth. Some of them are:

- Labor time might be extended as the baby would have a hard time getting past the pelvis.

- Forceps might be required, which could cause cranial damage.

- Baby’s head shape might be altered due to difficulty while moving through the birth canal.

- Baby may go through stress during delivery as it would be difficult birth and may require a caesarean.

- Injuries may occur to the baby’s spinal cord due to trauma.

- Increased risk of cerebral hemorrhage in the baby as the head may take in damage.

As explained already, a baby in brow presentation might not have enough space to move downwards towards the cervix. If this happens, there are a few methods your doctor might implement to reduce the complications of natural birth. These methods require medical skill and enough space within the cervix to be attempted.

- Ventouse Birth: In this case, your doctor will use a small vacuum extraction device known as a ventouse to pull the baby’s head towards their chest. This method can be used even after you have begun to push.

- Manual Rotation: After the cervix undergoes complete dilation, your doctor might attempt to move the baby’s head into the correct position using their hands.

As there are several complications linked with brow presentations, here are some precautions for you to take before and after labour to have a successful pregnancy.

- Choose a doctor who is accomplished in obstetrics and gynaecology, so they are experienced in dealing with any potential outcome.

- Visit your doctor regularly, especially at the end of your third trimester.

- If you have been diagnosed with brow presentation, do not hesitate to go for a caesarean if strongly recommended by your doctor, as it dramatically reduces the risks involved.

Babies might end up with abnormally shaped heads if they go through vaginal birth with a brow presentation. However, as their heads are malleable, they will return to a normal shape in a few days. Extended labor might cause stress in your baby who has been stuck in an uncomfortable position the whole time. This might also lead to vertebral problems, so consult a paediatric osteopath if you are concerned.

Brow presentation can happen to anyone, so not encountering it in your first pregnancy does not mean you will not see during later pregnancies. Consume a balanced, nutritious diet, stay hydrated and get enough sleep. Avoiding tension and anxiety will help you stay strong for when your baby arrives.

Also Read : Preparing for Labour & Delivery – Smart Ways to Prepare for Childbirth

- RELATED ARTICLES

- MORE FROM AUTHOR

Anteverted Uterus & Pregnancy - Is It Normal?

Overcome Your Miscarriage Fears

How to Cope With Perineal Tears During Delivery

Baby With THREE Biological Parents Shocks The World!

When Can You Get an Abortion

Placental Abruption (Abruptio Placentae) During Pregnancy

Popular on parenting.

245 Rare Boy & Girl Names with Meanings

Top 22 Short Moral Stories For Kids

170 Boy & Girl Names That Mean 'Gift from God'

800+ Unique & Cute Nicknames for Boys & Girls

Latest posts.

90 Hilarious Winter Jokes for Kids to Make Holiday More Fun

60 Best Back to School Jokes for Kids to Start the Year With a Smile

100+ Heartfelt Thank You Messages and Quotes for Parents

150+ Step Daughter Quotes to Show Your Love

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Pan Afr Med J

Management of face presentation, face and lip edema in a primary healthcare facility case report, Mbengwi, Cameroon

Nzozone henry fomukong.

1 Microhealth Global Medical Centre, Mbengwi, Cameroon

2 Department of Medicine and Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

Ngouagna Edwin

Mandeng ma linwa edgar, ngwayu claude nkfusai.

3 Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Science, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

4 Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services (CBCHS), Yaoundé, Cameroon

Yunga Patience Ijang

5 Department of Public Health, School of Health Sciences, Catholic University of Central Africa, Box 1110, Yaoundé, Cameroon

Joyce Shirinde

6 School of Health Systems and Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria Private Bag X323, Gezina, Pretoria, 0001, Pretoria, South Africa

Samuel Nambile Cumber

7 Institute of Medicine, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine (EPSO), University of Gothenburg, Box 414, SE - 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden

8 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Face presentation is a rare obstetric event and most practitioners will go through their carriers without ever meeting one. Face presentation can be delivered vaginally only if the foetus is in the mentum anterior position. More than half of the cases of face presentation are delivered by caesarean section. Newborn infants with face presentation usually have severe facial oedema, facial bruising or ecchymosis. These syndromic facial features usually resolved within 24-48 hours.

Introduction

Face presentation is a rare unanticipated obstetric event characterized by a longitudinal lie and full extension of the foetal head on the neck with the occiput against the upper back [ 1 - 3 ]. Face presentation occurs in 0.1-0.2% of deliveries [ 3 - 5 ] but is more common in black women and in multiparous women [ 5 ]. Studies have shown that 60 per cent of face presentations have one or more of the following risk factors: small fetus, large fetus, high parity, previous caesarean section (CS), contracted pelvis, fetopelvic disproportion, cord around the neck multiple pregnancy, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, polyhydramnios, uterine or nuchal cord anomaly. But 40 per cent of face presentations occur with none of these factors [ 6 , 7 ]. A vaginal birth at term is possible only if the fetus is in the mentum anterior position. More than half of cases of face presentation are delivered by caesarean section [ 4 ]. Newborn infants with face presentation usually have severe facial edema, facial bruising or ecchymosis [ 8 ]. Repeated vaginal examination to assess the presenting part and the progress of labor may lead to bruises in the face as well as damage to the eyes.

Patient and observation