Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Two Decades Later, the Enduring Legacy of 9/11

Table of contents, a devastating emotional toll, a lasting historical legacy, 9/11 transformed u.s. public opinion, but many of its impacts were short-lived, u.s. military response: afghanistan and iraq, the ‘new normal’: the threat of terrorism after 9/11, addressing the threat of terrorism at home and abroad, views of muslims, islam grew more partisan in years after 9/11.

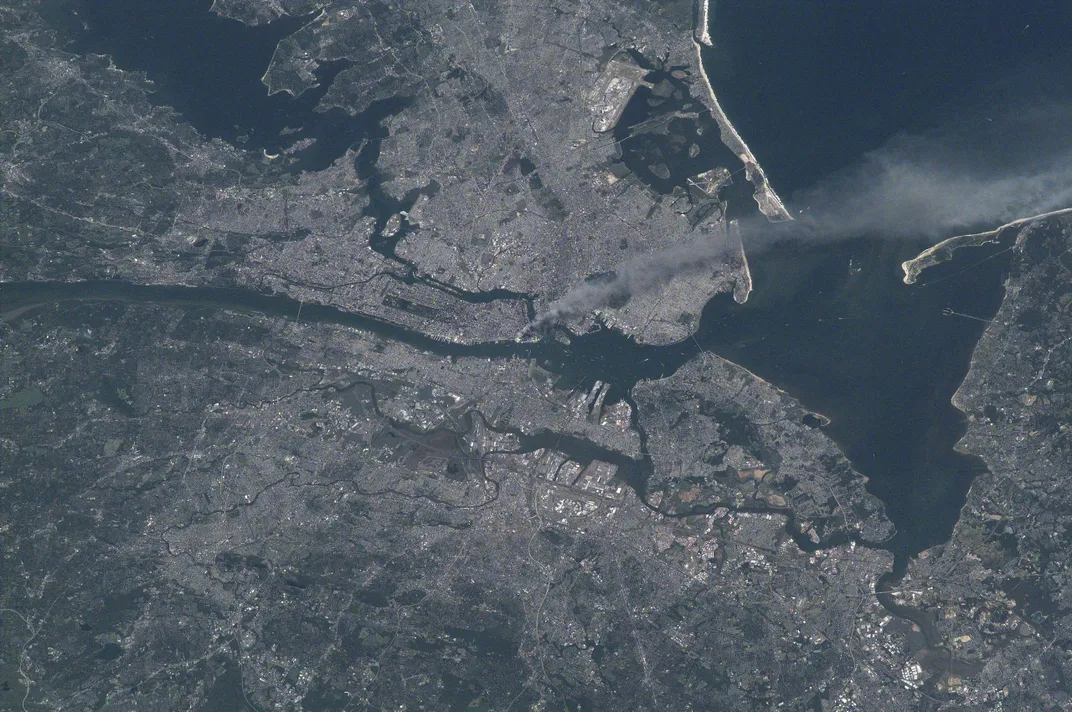

Americans watched in horror as the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, left nearly 3,000 people dead in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Nearly 20 years later, they watched in sorrow as the nation’s military mission in Afghanistan – which began less than a month after 9/11 – came to a bloody and chaotic conclusion.

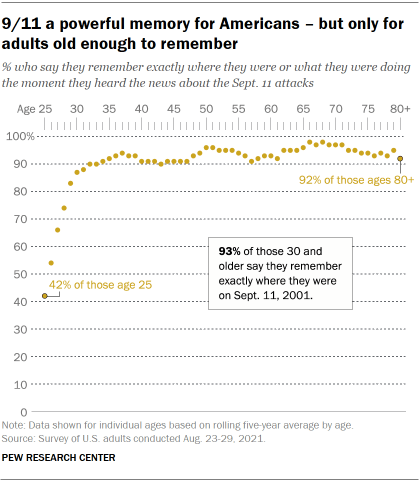

The enduring power of the Sept. 11 attacks is clear: An overwhelming share of Americans who are old enough to recall the day remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news. Yet an ever-growing number of Americans have no personal memory of that day, either because they were too young or not yet born.

A review of U.S. public opinion in the two decades since 9/11 reveals how a badly shaken nation came together, briefly, in a spirit of sadness and patriotism; how the public initially rallied behind the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, though support waned over time; and how Americans viewed the threat of terrorism at home and the steps the government took to combat it.

As the country comes to grips with the tumultuous exit of U.S. military forces from Afghanistan, the departure has raised long-term questions about U.S. foreign policy and America’s place in the world. Yet the public’s initial judgments on that mission are clear: A majority endorses the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan, even as it criticizes the Biden administration’s handling of the situation. And after a war that cost thousands of lives – including more than 2,000 American service members – and trillions of dollars in military spending, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that 69% of U.S. adults say the United States has mostly failed to achieve its goals in Afghanistan.

This examination of how the United States changed in the two decades following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks is based on an analysis of past public opinion survey data from Pew Research Center, news reports and other sources.

Current data is from a Pew Research Center survey of 10,348 U.S. adults conducted Aug. 23-29, 2021. Most of the interviewing was conducted before the Aug. 26 suicide bombing at Kabul airport, and all of it was conducted before the completion of the evacuation. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology .

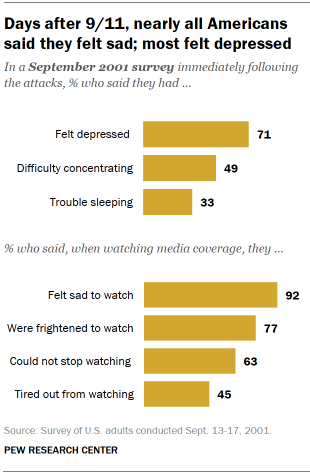

Shock, sadness, fear, anger: The 9/11 attacks inflicted a devastating emotional toll on Americans. But as horrible as the events of that day were, a 63% majority of Americans said they couldn’t stop watching news coverage of the attacks.

Our first survey following the attacks went into the field just days after 9/11, from Sept. 13-17, 2001. A sizable majority of adults (71%) said they felt depressed, nearly half (49%) had difficulty concentrating and a third said they had trouble sleeping.

It was an era in which television was still the public’s dominant news source – 90% said they got most of their news about the attacks from television, compared with just 5% who got news online – and the televised images of death and destruction had a powerful impact. Around nine-in-ten Americans (92%) agreed with the statement, “I feel sad when watching TV coverage of the terrorist attacks.” A sizable majority (77%) also found it frightening to watch – but most did so anyway.

Americans were enraged by the attacks, too. Three weeks after 9/11 , even as the psychological stress began to ease somewhat, 87% said they felt angry about the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon.

Fear was widespread, not just in the days immediately after the attacks, but throughout the fall of 2001. Most Americans said they were very (28%) or somewhat (45%) worried about another attack . When asked a year later to describe how their lives changed in a major way, about half of adults said they felt more afraid, more careful, more distrustful or more vulnerable as a result of the attacks.

Even after the immediate shock of 9/11 had subsided, concerns over terrorism remained at higher levels in major cities – especially New York and Washington – than in small towns and rural areas. The personal impact of the attacks also was felt more keenly in the cities directly targeted: Nearly a year after 9/11, about six-in-ten adults in the New York (61%) and Washington (63%) areas said the attacks had changed their lives at least a little, compared with 49% nationwide. This sentiment was shared by residents of other large cities. A quarter of people who lived in large cities nationwide said their lives had changed in a major way – twice the rate found in small towns and rural areas.

The impacts of the Sept. 11 attacks were deeply felt and slow to dissipate. By the following August, half of U.S. adults said the country “had changed in a major way” – a number that actually increased , to 61%, 10 years after the event .

A year after the attacks, in an open-ended question, most Americans – 80% – cited 9/11 as the most important event that had occurred in the country during the previous year. Strikingly, a larger share also volunteered it as the most important thing that happened to them personally in the prior year (38%) than mentioned other typical life events, such as births or deaths. Again, the personal impact was much greater in New York and Washington, where 51% and 44%, respectively, pointed to the attacks as the most significant personal event over the prior year.

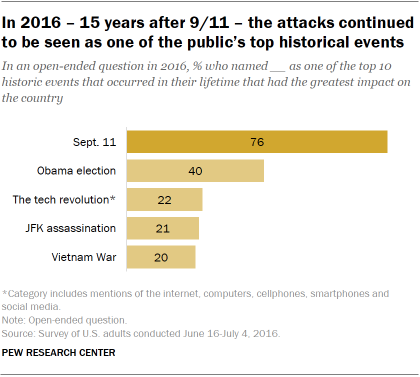

Just as memories of 9/11 are firmly embedded in the minds of most Americans old enough to recall the attacks, their historical importance far surpasses other events in people’s lifetimes. In a survey conducted by Pew Research Center in association with A+E Networks’ HISTORY in 2016 – 15 years after 9/11 – 76% of adults named the Sept. 11 attacks as one of the 10 historical events of their lifetime that had the greatest impact on the country. The election of Barack Obama as the first Black president was a distant second, at 40%.

The importance of 9/11 transcended age, gender, geographic and even political differences. The 2016 study noted that while partisans agreed on little else that election cycle, more than seven-in-ten Republicans and Democrats named the attacks as one of their top 10 historic events.

It is difficult to think of an event that so profoundly transformed U.S. public opinion across so many dimensions as the 9/11 attacks. While Americans had a shared sense of anguish after Sept. 11, the months that followed also were marked by rare spirit of public unity.

Patriotic sentiment surged in the aftermath of 9/11. After the U.S. and its allies launched airstrikes against Taliban and al-Qaida forces in early October 2001, 79% of adults said they had displayed an American flag. A year later, a 62% majority said they had often felt patriotic as a result of the 9/11 attacks.

Moreover, the public largely set aside political differences and rallied in support of the nation’s major institutions, as well as its political leadership. In October 2001, 60% of adults expressed trust in the federal government – a level not reached in the previous three decades, nor approached in the two decades since then.

George W. Bush, who had become president nine months earlier after a fiercely contested election, saw his job approval rise 35 percentage points in the space of three weeks. In late September 2001, 86% of adults – including nearly all Republicans (96%) and a sizable majority of Democrats (78%) – approved of the way Bush was handling his job as president.

Americans also turned to religion and faith in large numbers. In the days and weeks after 9/11, most Americans said they were praying more often. In November 2001, 78% said religion’s influence in American life was increasing, more than double the share who said that eight months earlier and – like public trust in the federal government – the highest level in four decades .

Public esteem rose even for some institutions that usually are not that popular with Americans. For example, in November 2001, news organizations received record-high ratings for professionalism. Around seven-in-ten adults (69%) said they “stand up for America,” while 60% said they protected democracy.

Yet in many ways, the “9/11 effect” on public opinion was short-lived. Public trust in government, as well as confidence in other institutions, declined throughout the 2000s. By 2005, following another major national tragedy – the government’s mishandling of the relief effort for victims of Hurricane Katrina – just 31% said they trusted the federal government, half the share who said so in the months after 9/11. Trust has remained relatively low for the past two decades: In April of this year, only 24% said they trusted the government just about always or most of the time.

Bush’s approval ratings, meanwhile, never again reached the lofty heights they did shortly after 9/11. By the end of his presidency, in December 2008, just 24% approved of his job performance.

With the U.S. now formally out of Afghanistan – and with the Taliban firmly in control of the country – most Americans (69%) say the U.S. failed in achieving its goals in Afghanistan.

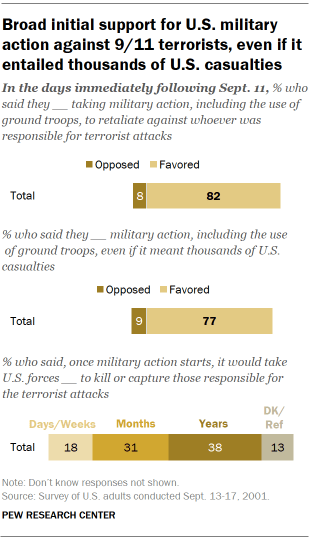

But 20 years ago, in the days and weeks following 9/11, Americans overwhelmingly supported military action against those responsible for the attacks. In mid-September 2001, 77% favored U.S. military action, including the deployment of ground forces, “to retaliate against whoever is responsible for the terrorist attacks, even if that means U.S. armed forces might suffer thousands of casualties.”

Many Americans were impatient for the Bush administration to give the go-ahead for military action. In a late September 2001 survey, nearly half the public (49%) said their larger concern was that the Bush administration would not strike quickly enough against the terrorists; just 34% said they worried the administration would move too quickly.

Even in the early stages of the U.S. military response, few adults expected a military operation to produce quick results: 69% said it would take months or years to dismantle terrorist networks, including 38% who said it would take years and 31% who said it would take several months. Just 18% said it would take days or weeks.

The public’s support for military intervention was evident in other ways as well. Throughout the fall of 2001, more Americans said the best way to prevent future terrorism was to take military action abroad rather than build up defenses at home. In early October 2001, 45% prioritized military action to destroy terrorist networks around the world, while 36% said the priority should be to build terrorism defenses at home.

Initially, the public was confident that the U.S. military effort to destroy terrorist networks would succeed. A sizable majority (76%) was confident in the success of this mission, with 39% saying they were very confident.

Support for the war in Afghanistan continued at a high level for several years to come. In a survey conducted in early 2002, a few months after the start of the war, 83% of Americans said they approved of the U.S.-led military campaign against the Taliban and al-Qaida in Afghanistan. In 2006, several years after the United States began combat operations in Afghanistan, 69% of adults said the U.S. made the right decision in using military force in Afghanistan. Only two-in-ten said it was the wrong decision.

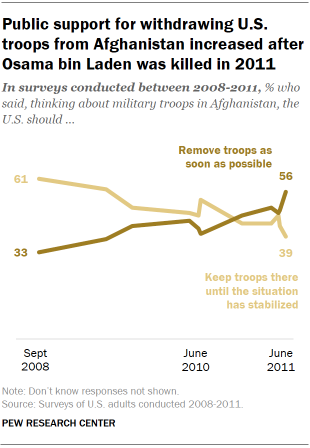

But as the conflict dragged on, first through Bush’s presidency and then through Obama’s administration, support wavered and a growing share of Americans favored the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. In June 2009, during Obama’s first year in office, 38% of Americans said U.S. troops should be removed from Afghanistan as soon as possible. The share favoring a speedy troop withdrawal increased over the next few years. A turning point came in May 2011, when U.S. Navy SEALs launched a risky operation against Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan and killed the al-Qaida leader.

The public reacted to bin Laden’s death with more of a sense of relief than jubilation . A month later, for the first time , a majority of Americans (56%) said that U.S. forces should be brought home as soon as possible, while 39% favored U.S. forces in the country until the situation had stabilized.

Over the next decade, U.S. forces in Afghanistan were gradually drawn down, in fits and starts, over the administrations of three presidents – Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Meanwhile, public support for the decision to use force in Afghanistan, which had been widespread at the start of the conflict, declined . Today, after the tumultuous exit of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, a slim majority of adults (54%) say the decision to withdraw troops from the country was the right decision; 42% say it was the wrong decision.

There was a similar trajectory in public attitudes toward a much more expansive conflict that was part of what Bush termed the “war on terror”: the U.S. war in Iraq. Throughout the contentious, yearlong debate before the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Americans widely supported the use of military force to end Saddam Hussein’s rule in Iraq.

Importantly, most Americans thought – erroneously, as it turned out – there was a direct connection between Saddam Hussein and the 9/11 attacks. In October 2002, 66% said that Saddam helped the terrorists involved in the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

In April 2003, during the first month of the Iraq War, 71% said the U.S. made the right decision to go to war in Iraq. On the 15th anniversary of the war in 2018, just 43% said it was the right decision. As with the case with U.S. involvement in Afghanistan, more Americans said that the U.S. had failed (53%) than succeeded (39%) in achieving its goals in Iraq.

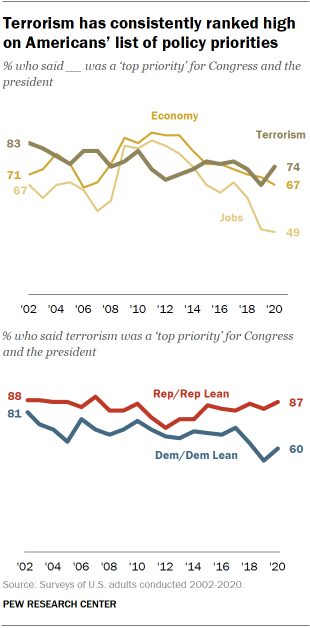

There have been no terrorist attacks on the scale of 9/11 in two decades, but from the public’s perspective, the threat has never fully gone away. Defending the country from future terrorist attacks has been at or near the top of Pew Research Center’s annual survey on policy priorities since 2002.

In January 2002, just months after the 2001 attacks, 83% of Americans said “defending the country from future terrorist attacks” was a top priority for the president and Congress, the highest for any issue. Since then, sizable majorities have continued to cite that as a top policy priority.

Majorities of both Republicans and Democrats have consistently ranked terrorism as a top priority over the past two decades, with some exceptions. Republicans and Republican-leaning independents have remained more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say defending the country from future attacks should be a top priority. In recent years, the partisan gap has grown larger as Democrats began to rank the issue lower relative to other domestic concerns. The public’s concerns about another attack also remained fairly steady in the years after 9/11, through near-misses and the federal government’s numerous “Orange Alerts” – the second-most serious threat level on its color-coded terrorism warning system.

A 2010 analysis of the public’s terrorism concerns found that the share of Americans who said they were very concerned about another attack had ranged from about 15% to roughly 25% since 2002. The only time when concerns were elevated was in February 2003, shortly before the start of the U.S. war in Iraq.

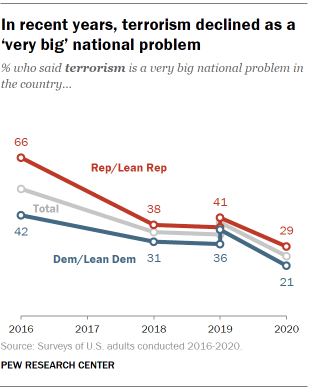

In recent years, the share of Americans who point to terrorism as a major national problem has declined sharply as issues such as the economy, the COVID-19 pandemic and racism have emerged as more pressing problems in the public’s eyes.

In 2016, about half of the public (53%) said terrorism was a very big national problem in the country. This declined to about four-in-ten from 2017 to 2019. Last year, only a quarter of Americans said that terrorism was a very big problem.

This year, prior to the U.S. withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan and the subsequent Taliban takeover of the country, a somewhat larger share of adults said domestic terrorism was a very big national problem (35%) than said the same about international terrorism . But much larger shares cited concerns such as the affordability of health care (56%) and the federal budget deficit (49%) as major problems than said that about either domestic or international terrorism.

Still, recent events in Afghanistan raise the possibility that opinion could be changing, at least in the short term. In a late August survey, 89% of Americans said the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan was a threat to the security of the U.S., including 46% who said it was a major threat.

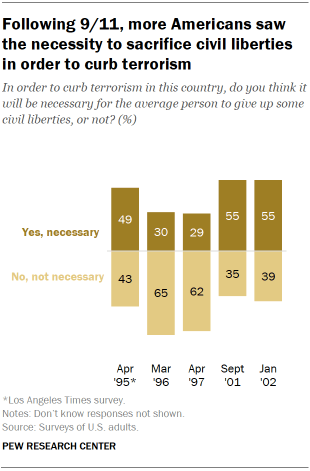

Just as Americans largely endorsed the use of U.S. military force as a response to the 9/11 attacks, they were initially open to a variety of other far-reaching measures to combat terrorism at home and abroad. In the days following the attack, for example, majorities favored a requirement that all citizens carry national ID cards, allowing the CIA to contract with criminals in pursuing suspected terrorists and permitting the CIA to conduct assassinations overseas when pursuing suspected terrorists.

However, most people drew the line against allowing the government to monitor their own emails and phone calls (77% opposed this). And while 29% supported the establishment of internment camps for legal immigrants from unfriendly countries during times of tension or crisis – along the lines of those in which thousands of Japanese American citizens were confined during World War II – 57% opposed such a measure.

It was clear that from the public’s perspective, the balance between protecting civil liberties and protecting the country from terrorism had shifted. In September 2001 and January 2002, 55% majorities said that, in order to curb terrorism in the U.S., it was necessary for the average citizen to give up some civil liberties. In 1997, just 29% said this would be necessary while 62% said it would not.

For most of the next two decades, more Americans said their bigger concern was that the government had not gone far enough in protecting the country from terrorism than said it went too far in restricting civil liberties.

The public also did not rule out the use of torture to extract information from terrorist suspects. In a 2015 survey of 40 nations, the U.S. was one of only 12 where a majority of the public said the use of torture against terrorists could be justified to gain information about a possible attack.

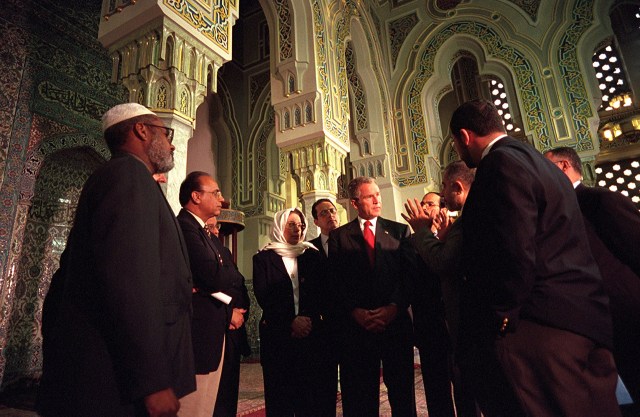

Concerned about a possible backlash against Muslims in the U.S. in the days after 9/11, then-President George W. Bush gave a speech to the Islamic Center in Washington, D.C., in which he declared: “Islam is peace.” For a brief period, a large segment of Americans agreed. In November 2001, 59% of U.S. adults had a favorable view of Muslim Americans, up from 45% in March 2001, with comparable majorities of Democrats and Republicans expressing a favorable opinion.

This spirit of unity and comity was not to last. In a September 2001 survey, 28% of adults said they had grown more suspicious of people of Middle Eastern descent; that grew to 36% less than a year later.

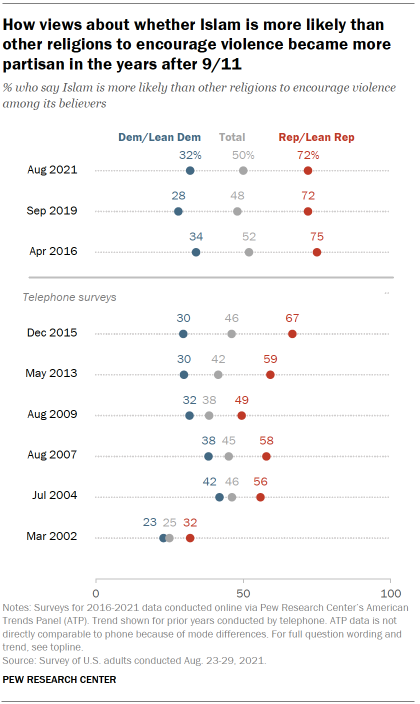

Republicans, in particular, increasingly came to associate Muslims and Islam with violence. In 2002, just a quarter of Americans – including 32% of Republicans and 23% of Democrats – said Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence among its believers. About twice as many (51%) said it was not.

But within the next few years, most Republicans and GOP leaners said Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence. Today, 72% of Republicans express this view, according to an August 2021 survey.

Democrats consistently have been far less likely than Republicans to associate Islam with violence. In the Center’s latest survey, 32% of Democrats say this. Still, Democrats are somewhat more likely to say this today than they have been in recent years: In 2019, 28% of Democrats said Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence among its believers than other religions.

The partisan gap in views of Muslims and Islam in the U.S. is evident in other meaningful ways. For example, a 2017 survey found that half of U.S. adults said that “Islam is not part of mainstream American society” – a view held by nearly seven-in-ten Republicans (68%) but only 37% of Democrats. In a separate survey conducted in 2017, 56% of Republicans said there was a great deal or fair amount of extremism among U.S. Muslims, with fewer than half as many Democrats (22%) saying the same.

The rise of anti-Muslim sentiment in the aftermath of 9/11 has had a profound effect on the growing number of Muslims living in the United States. Surveys of U.S. Muslims from 2007-2017 found increasing shares saying they have personally experienced discrimination and received public expression of support.

It has now been two decades since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon and the crash of Flight 93 – where only the courage of passengers and crew possibly prevented an even deadlier terror attack.

For most who are old enough to remember, it is a day that is impossible to forget. In many ways, 9/11 reshaped how Americans think of war and peace, their own personal safety and their fellow citizens. And today, the violence and chaos in a country half a world away brings with it the opening of an uncertain new chapter in the post-9/11 era.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Terrorism & Political Violence — 9/11

Essays on 9/11

The causes, effects, and lessons of 9/11, somebody blew up america: a critical analysis, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Effects of 9/11 Attack on America

A tragedy for all americans: the 9/11 terrorist attack, how 9/11 changed people’s lives in the usa, history of terrorist attack in united states, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Impact of The 9/11 Tragedy on The Marketplace in The Reluctant Fundamentalist

Insight on the twin towers attack, president george w. bush's speech after the 9/11 attacks: a critique, the reasons why it is important to address the 9/11 in literature, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Conspiracy Theory: No Truth About 9/11

9/11 attacks: facts, background and impact, the events that led to the 9/11 crisis in the united states, different reactions on the 9/11 tragedy in america, the 9/11 terrorist attacks: the dark day in us history, analysis of the 9/11 attacs in terms of aristotelian courage, 9/11: discussion about freedom in the united states, analysis of 9/11 incident as a conspiracy theory, an analysis of the united states foreign policy in the post 9/11 period, a research of 9/11 conspiracy theory, the growth of islamophobia after 9/11 in the united states of america, terrorism on american soil, 11 of september 2001: analysis of the tragedy and its conspiracies, the patriot act should be abolished, depiction of 9/11 in extremely loud and incredibly close movie, the history and background of 9/11 memorial, ian mcewan’s saturday: criticism of the post-9/11 society, cia's torture of detainees after twin towers' tragedy, 9/11: a day never forgotten, parallels between pearl harbor and 9/11 attack.

September 11, 2001

New York City, New York, U.S.

The tragic events of September 11, 2001, commonly known as the 9/11 attacks, involved a series of coordinated hijackings and deliberate suicide attacks carried out by 19 militants affiliated with the extremist Islamic group al-Qaeda. These attacks, which remain the deadliest acts of terrorism on American soil, targeted several locations in the United States. The hijackers were successful in crashing two planes into the iconic North and South Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, causing their eventual collapse. Another plane struck the Pentagon, the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense, located in Arlington, Virginia. The fourth plane, intended for a federal government building in Washington, D.C., was heroically thwarted by passengers who revolted, resulting in its crash in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. These heinous acts had a profound impact on global security, reshaping the course of international relations and forever altering the lives of countless individuals affected by the tragedy.

The 9/11 attacks were a culmination of various historical factors and events that set the stage for this tragic event. The primary cause behind the attacks can be traced to the rise of Islamic extremism, particularly the extremist group al-Qaeda, led by Osama bin Laden. It emerged as a response to perceived injustices faced by Muslims, including the presence of American military forces in the Middle East and U.S. foreign policies in the region. The prerequisites leading to the attacks involved a combination of factors, such as ideological radicalization, recruitment efforts, and meticulous planning by the terrorists. These efforts aimed to exploit existing vulnerabilities within the aviation security system and target symbolic landmarks in the United States. Additionally, geopolitical conflicts, such as the Soviet-Afghan War and the Gulf War, played a role in shaping the ideological landscape and providing a breeding ground for extremist ideologies. The attacks were also facilitated by intelligence failures and a lack of coordination between various agencies responsible for counterterrorism efforts.

The effects of the 9/11 attacks were far-reaching and had a profound impact on various aspects of society. Primarily, the attacks resulted in the loss of thousands of innocent lives and caused immense physical destruction, particularly with the collapse of the World Trade Center towers in New York City and the damage to the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. The attacks had significant socio-political consequences. They led to a heightened sense of fear and insecurity within the United States and around the world. The incident prompted the implementation of stricter security measures, including enhanced airport screenings and increased surveillance efforts, to prevent future terrorist acts. Moreover, the attacks influenced U.S. foreign policy, leading to military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq. The attacks also had economic repercussions. The destruction of the World Trade Center had a severe impact on global financial markets and the economy, leading to a decline in stock markets and increased job losses. Additionally, the attacks had a lasting psychological impact, causing trauma and grief among survivors, families of the victims, and communities affected by the events.

The 9/11 attacks have had a significant impact on media and literature, with numerous works exploring the events, their aftermath, and their implications. Various forms of media, including films, documentaries, books, and poems, have depicted the 9/11 attacks and their consequences. One notable example is the film "United 93" (2006), directed by Paul Greengrass. The movie reconstructs the events aboard United Airlines Flight 93, which crashed in Pennsylvania after passengers attempted to regain control from the hijackers. The film offers a gripping and emotional portrayal of the heroic actions taken by the passengers in the face of tragedy. Another prominent work is "Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close" (2005), a novel by Jonathan Safran Foer. The book follows a young boy named Oskar Schell, who lost his father in the World Trade Center collapse. Through Oskar's perspective, the novel explores themes of grief, trauma, and the search for meaning in the aftermath of the attacks.

The 9/11 attacks had a profound impact on public opinion, eliciting a range of responses and shaping perceptions worldwide. In the immediate aftermath, people expressed feelings of anger towards the perpetrators and a desire for justice to be served. The attacks also sparked debates and discussions on various topics, including national security, terrorism, and foreign policy. Public opinion regarding the government's response to the attacks and the subsequent military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq varied, with some supporting the actions taken and others expressing concerns about civil liberties and the potential escalation of conflicts. Furthermore, the 9/11 attacks prompted increased awareness and scrutiny of issues related to religious tolerance, Islamophobia, and the treatment of Muslim communities. Public discourse on these topics became more prominent, reflecting a heightened focus on understanding and combating prejudice.

1. The collapse of the Twin Towers following the 9/11 attacks remains a striking fact. The South Tower (WTC 2) collapsed only 56 minutes after being hit by United Airlines Flight 175, while the North Tower (WTC 1) collapsed 102 minutes after being struck by American Airlines Flight 11. These unprecedented structural failures shocked the world and demonstrated the devastating impact of the attacks. 2. The 9/11 attacks resulted in a tragic loss of life. In total, 2,977 people from over 90 countries lost their lives in the attacks on the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and aboard United Airlines Flight 93. Among the casualties were not only office workers and first responders but also individuals from diverse backgrounds, including tourists, airline passengers, and individuals attending business meetings. 3. Economic consequences: The attacks had a profound impact on the economy, not only in terms of immediate destruction but also long-term effects. It is estimated that the attacks caused a loss of $123 billion in economic output during the first two to four weeks. Additionally, sectors such as tourism, aviation, and finance experienced significant disruptions and faced substantial financial losses, leading to a ripple effect on employment and global markets.

The topic of the 9/11 attacks holds significant importance as it marks a pivotal moment in contemporary history that changed the global landscape in numerous ways. Understanding and exploring this event through an essay allows for a comprehensive examination of its profound impact on society, politics, security, and international relations. Firstly, the 9/11 attacks shattered the sense of security and invulnerability that many nations had previously enjoyed. It exposed vulnerabilities in security systems, leading to significant changes in counterterrorism measures and policies worldwide. Secondly, the attacks prompted a reevaluation of international relations and the United States' role in global affairs. It fueled the war on terror, leading to military interventions, the establishment of new alliances, and shifts in foreign policies. Furthermore, the 9/11 attacks raised important questions about religious extremism, ideological motivations, and the delicate balance between security and civil liberties. Examining these aspects in an essay fosters critical thinking and provides an opportunity to delve into the complexities surrounding terrorism and its aftermath.

1. National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (2004). The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. W. W. Norton & Company. 2. Summers, A., & Swan, R. (2011). The Eleventh Day: The Full Story of 9/11 and Osama bin Laden. Ballantine Books. 3. Jenkins, B. M. (2006). The 9/11 Wars. Hill and Wang. 4. Smith, M. L. (2011). Why War? The Cultural Logic of Iraq, the Gulf War, and Suez. University of Chicago Press. 5. Bowden, M. (2006). Guests of the Ayatollah: The Iran Hostage Crisis: The First Battle in America's War with Militant Islam. Grove Press. 6. Wright, L. (2006). The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. Vintage. 7. Bamford, J. (2008). The Shadow Factory: The Ultra-Secret NSA from 9/11 to the Eavesdropping on America. Anchor Books. 8. Thompson, W., & Thompson, S. (2011). The Disappearance of the Social in American Social Psychology. Cambridge University Press. 9. Boyle, M. (2007). Media Mythmakers: How Journalists, Activists, and Advertisers Mislead Us. Potomac Books. 10. Zelikow, P., & Shenon, P. (2021). The 9/11 Commission Report: Omissions and Distortions. Interlink Publishing Group.

Relevant topics

- Andrew Jackson

- Abraham Lincoln

- Electoral College

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

How 9/11 Changed the World

The World Trade Center buildings in New York City collapsed on September 11, 2001, after two airplanes slammed into the twin towers in a terrorist attack. Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

BU faculty reflect on how that day’s events have reshaped our lives over the last 20 years

Bu today staff.

Saturday, September 11, 2021, marks the 20th anniversary of 9/11, the largest terrorist attack in history. On that Tuesday morning, 19 al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked four American commercial flights destined for the West Coast and intentionally crashed them. Two planes—American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175—departed from Boston and Flight 11 struck New York City’s World Trade Center North Tower at 8:46 am and Flight 175 the South Tower at 9:03 am, resulting in the collapse of both towers. A third plane, American Airlines Flight 77, leaving from Dulles International Airport in Virginia, crashed into the Pentagon at 9:37 am, and the final plane, United Airlines Flight 93, departing from Newark, N.J., crashed in a field in Shanksville, Pa., at 10:03 am, after passengers stormed the cockpit and tried to subdue the hijackers.

In the space of less than 90 minutes on a late summer morning, the world changed. Nearly 3,000 people were killed that day and the United States soon found itself mired in what would become the longest war in its history, a war that cost an estimated $8 trillion . The events of 9/11 not only reshaped the global response to terrorism, but raised new and troubling questions about security, privacy, and treatment of prisoners. It reshaped US immigration policies and led to a surge in discrimination, racial profiling, and hate crimes.

In observance of the anniversary, BU Today reached out to faculty across Boston University—experts in international relations, international security, immigration law, global health, terrorism, and ethics—and asked each to address this question: “How has the world changed as a result of 9/11?”

Find a list of all those with ties to the BU community killed on 9/11 here.

Explore Related Topics:

- Immigration

- International Relations

- Pardee School of Global Studies

- Public Policy

- Share this story

- 43 Comments Add

BU Today staff Profile

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 43 comments on How 9/11 Changed the World

this is very scary to me.

Yes this is very scary

This was a very sad moment in time but we need to remember the people that sacrificed themselves to save us and the people that died during this event. It was sad but at least it brought us closer together. I wonder what the world would be like if 9/11 never happened?..

Yes that is a good thing to rember…

We will all remember 9/11, a very important moment in our life, and we honor the ones who sacrificed their lives to save others in there.

It changed the world forever, it is infact a painful memory to remember

I feel bad for all the families that had family and friends die.

i feel bad for all the people and their family and friends that died

9/11 is tragic and it will always be remembered though I have to say that saying 9/11 changed the word is quite an overstatement. More like how it changes America in certain ways and the ones responsible for it but saying something like what you said makes it sound like it was Armageddon or something.

Whether or not those of us in other countries like it, for the last several decades and certainly still in the current time, when something changes the USA in significant ways that impact policy, legislation, education, the economy, health care, etc. (not to mention the ways in which public opinion drives the American political machine), the US’s presence on the international stage means those changes ripple outward through their foreign policy, treatment of both residents/citizens of the USA and local people where the USA has a military, economic and/or other presence around the world.

The complex web of international agreements, alliances, organizational memberships, and financial interdependency means that events that happen locally often have both direct and indirect implications, short and long term, around the world, for individuals and for entire segments of society.

As for the direct results of 20 years of military response to 9/11 on civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan, it certainly changed their world.

The original BU 9/11 Memorial webpage is still up: https://www.bu.edu/remember/index.html

Reading through the remembrances from that day onward …

Omg scary .

I honor them all.

I wonder how much time people had to get out before the building collapsed

the south tower collapsed in 10 seconds.

Yes but it didnt colapse untill 56 minutes after it was hit

Shall all the people who risked their lives, never be forgotten.

am i blind or was there no mention of how it actually affected the world afterwards??

I know right?

My dad died in 9/11, He was a great pilot

Wow. I’m really sorry for your loss I hope you can still go far in life even without your dad. Sometimes you just have to go with your gut and let them go.

i dont really think you understood that comment

i just read the story and im so sade for the dad that died . If i was there i wouls of creiyed and i saw someone in the chare that someone dad died and i felt so bad when i saw the comment but i dont know if that is real but if it is i feal bad for you if my dad died or my mom i woulld been so sade i would never get over it but this story changed my life when i read it.Also 1 thing i hoop not to any dads diead because i feel bad fo thos kids.

yo all the dads and moms died all of them will never get forgoten every single one of them

Never forget, always remember

everyone is talking about the twin towers but what about the pentagon.

I know, right?

it is super scary

Sorry for all the people who Lost their family

Thanks for helping me with this report, and yes so sorry for all yall who lost family

So, so sorry to all y’all who lost family

I am deeply sorry for anyone who lost family, friends, co workers, or anybody you once knew. This really was a tragedy to so many.

my dad almost died from the tower

very scary but needs too be remembered!

I have to say this is most definitely a U.S. American write up. Saying the word is an overstatement in many ways. It would be more better if you were to specifically point out you mean the US and those others involved with the attacks. Overall if we are going to be completely factual “people/individuals” are the ones who change things depending on whatever. The world changes every day since the start of time.

While I agree with your first point, I would say that the attacks did in fact change the world. At the very least, they changed the way airline security is done everywhere.

great article,

I believe that the people, who sacrificed their lives in flight 93, the one that crashed in Pennsylvania, resonated the most with me, as it could have gone anywhere, and they sacrificed themselves to save more. I am deeply sorry for all losses, but I hope we remember this crucial moment in history to learn from our mistakes in global affairs, but also honor those who sacrificed themselves in all the attacks.

Post a comment. Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest from BU Today

Kahn award will carry theater arts major madeline riddick-seals back to alabama, commencement 2024: what you need to know, pov: decision to reclassify marijuana as a less dangerous drug is long overdue, esl classes offered to bu dining services workers, sargent senior gives back to his native nairobi—through sports, providing better support to disabled survivors of sexual assault, class of 2024: songs that remind you of your last four years at boston university, cloud computing platform cloudweaver wins at spring 2024 spark demo day, a birder’s guide to boston university, boston teens pitch biotech concepts to bu “investors” at biological design center’s stem pathways event, the weekender: may 9 to 12, dean sandro galea leaving bu’s school of public health for washu opportunity, meet the 2024 john s. perkins award winners, comm ave runway: may edition, stitching together the past, two bu faculty honored with outstanding teaching awards, advice to the class of 2024: “say thank you”, school of visual arts annual bfa thesis exhibitions celebrate works by 33 bfa seniors, q&a: why are so many people leaving massachusetts, killers of the flower moon author, and bu alum, david grann will be bu’s 151st commencement speaker.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Teaching Ideas

10 Ways to Teach About 9/11 With The New York Times

Ideas for helping students think about how the Sept. 11 attacks have changed our nation and world.

By Nicole Daniels and Michael Gonchar

Sept. 11, 2001 , is one of those rare days that, if you ask most adults what they remember, they can tell you exactly where they were, whom they were with and what they were thinking. It is a day seared in memory. But for students who were born in a post- 9/11 world and have grown up in the aftermath, it is complex history that needs to be remembered, taught and analyzed like any other historical event.

Twenty years ago, four commercial planes were hijacked by operatives from the radical Islamist group Al Qaeda. One plane was flown into the Pentagon outside Washington, D.C., and two others were flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York. A fourth hijacked plane crashed in Shanksville, Pa. Almost 3,000 people died that day, including more than 400 emergency workers.

In the wake of those attacks, the United States initiated a global “war on terror” to destroy Al Qaeda — a campaign that expanded into decades-long wars in Afghanistan, Iraq (even though Iraq was not responsible for Sept. 11 ) and elsewhere. In the wake of Sept. 11, the United States changed in other fundamental ways as well, from increased police surveillance to a rise in Islamophobia .

Below, we provide a range of activities that use resources from The New York Times, including archival front pages and photographs, first-person accounts, and analysis pieces published for the 20th anniversary . But we also suggest ideas borrowed from other education organizations like the Choices Program , RetroReport , the 9/11 Memorial and Museum and the Newseum .

On Sept. 30, we are hosting a free event, featuring Times journalists, for students that will look at how Sept. 11 has shaped a generation of young people who grew up in its aftermath. Teachers and students can register here , and students can submit their own videos with questions, many of which we hope to feature during the live event.

1. Reflect on What 9/11 Means to You

In the essay “ What Does It Mean to ‘Never Forget’? ,” Dan Barry writes:

Inevitably, someday there will be no one alive with a personal narrative of Sept. 11. Inevitably, the emotional impact of the day will fade a little bit, and then a little bit more, as time transforms a visceral lived experience into a dry history lesson. This transformation has already begun; ask any high school history teacher.

Or, ask any student. They are at the center of the transition that Mr. Barry describes.

Invite students to respond to one or more of the following questions, and share their responses with other students from around the world by responding to our related Student Opinion question :

What does Sept. 11 mean to you? Is it mostly a “dry history lesson” or does it resonate for you in deeper ways?

What do you know about the events that took place on Sept. 11? Where and how did you learn about them?

What questions do you have about that day and what happened next?

Have the events of Sept. 11 and its aftermath affected you personally in any way? If so, how? How do you think they may have shaped your generation as a whole?

Note: To ensure your class has a shared understanding of what happened on Sept. 11, you might want to have students watch this two-minute video or scroll through this interactive timeline , both created by the 9/11 Memorial and Museum. Alternatively, students can watch this five-minute video from the History Channel which is focused on the attacks at the World Trade Center.

2. Interview Someone Who Remembers

Although teenagers today are too young to have their own personal memories of Sept. 11, people they know and love do. The Choices Program at Brown University has created a lesson plan that walks students through the process of conducting an interview about Sept. 11 with someone they know while also considering the importance of oral history.

The accompanying student handout suggests questions that students may want to ask, such as: What were you doing on Sept. 11, 2001? How did you find out about the attacks?

After conducting their interviews, students can share what they have learned in small groups and with the class. They might even create an oral history book or site that they can share with future classes.

For inspiration or as mentor texts, students can take a look at this “Revisiting the Families” collection of short follow-up interviews and articles that Times reporters did to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the attacks. It offers small glimpses of those who lost family members, and of their lives since.

3. Revisit History’s First Draft

Newspapers have been described as “history’s first draft.” Reporters and editors from around the world who published on the morning of Sept. 12 had less than a day to figure out how to make sense of what happened for their readers.

Invite students to look closely at the New York Times front page (or the full paper ) from that day. They can click on the individual articles as well. What do they notice? What questions does the front page bring up for them? What do they learn about coverage on that first day?

Then they can investigate front pages from other newspapers from around the world and across the country. The Newseum (you’ll need to create a free account) provides images of front pages of over 100 newspapers from dozens of cities — from Anchorage and Richmond, Va., to Turku, Finland, and Osaka, Japan. Business Insider compiled some of the images from the Newseum’s archival, to show what the front pages of newspapers from around the world looked like on Sept. 12 .

Students can choose three or four front pages and take note of the similarities and differences that they see in coverage; what choices might they have made had they been editors that day; and what additional questions these front pages raise for them.

4. Look Closely at Archival Photos

Photographs can be a powerful and accessible way for students to learn more about what happened on and after Sept. 11. Students can study the New York Times photo collection “ The Towers’ Rise and Fall ,” which was originally published on the 10th anniversary of the attacks, to see what stories these 72 images tell about the World Trade Center, the terrorist attacks and the aftermath.

Students can closely investigate two or three images using our What’s Going On in This Picture? protocol from Visual Thinking Strategies :

What is going on in this picture?

What do you see that makes you say that?

What more can you find?

Or, you can invite students to take on the role of curator in a museum who is creating an exhibit about Sept. 11 in New York. They can choose only six to eight photographs to tell the story. Which images would they select and why?

5. Listen to and Read First-Person Stories

Students can watch one or more of the three-minute videos from the “ Portraits Redrawn ” series that was created by The Times for the 10th anniversary of Sept. 11. The six videos are all interviews with people who had a family member die in the attacks.

They can watch this 10-minute video from VICE in which a civilian mariner talks about assisting with the world’s largest boat lift that rescued half a million people from Lower Manhattan.

They can also watch this 12-minute RetroReport video that features interviews with emergency workers who survived the attacks at the World Trade Center and do all or part of this related lesson plan (and student activity ).

Or, students can read this article about a survivor navigating life with post-traumatic stress disorder after the attack on the World Trade Center.

After watching or reading, they can consider: What have you learned about Sept. 11 by hearing stories of survivors, families and people who died in the attacks? And, how do first-person stories change, or deepen, your understanding of what happened?

6. Consider the Importance of Memory

Op-docs: where the towers stood, the world trade center wreckage once smoldered here. now visitors come from around the world to learn, remember and grieve the loss of 9/11..

[somber music playing] [airplane engine] See it? Yeah. Am I just seeing things? Oh, jeez. Oh, they’re people. Oh. Oh, jeez, they’re people. They’re people. They’re people. [quiet music playing] I’m going to take us right here to this tree where there in shade and there is sun, so you could have which ever you prefer. So we don’t get in everyone’s way, if we can stay over here on the left hand side, we’ll be in good shape. The memorial is designed for you to make physical contact with it, to actually touch the names. So do not feel that the appropriate behavior that shows respect is to be standoffish. It is not. The only thing that we do ask — and I really doubt that any of you would have the impulse to do this anyhow — do not put things on the name. Coats, elbows, cups, bags, anything like that. The other thing I want to say to you is this was truly — you’re an international group of people — this was the World Trade Center. People from over 90 countries died here that morning. They were Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, atheists. Some made their way in the world washing dishes, others ran powerful companies, but almost every single one of them dies that morning because they do something that all of us do with most of our lives — they woke up and they went to work. [somber music playing] Excuse me. Hello. Hello, hello, hello. There’s no smoking in the plaza. No smoking in the plaza. That’s quite all right. Thank you. So I want to talk to you about the pools. Directly in front of you is the south pool. The south pool stands in the footprint of the South Tower, World Trade Center number two. So that’s exactly where World Trade Center number two stood. Can everyone see that line of trees that goes around the pool? That line of trees represents the outer wall of the building. So that means in a few minutes when we go up to see the falls and you go past those trees, you will be standing in what was once the lobby of World Trade Center number two. You’re going to see the falls. The falls come out in individual rivulets, one for each person killed on 9/11. Goes down about 20 feet or so into a huge pool. In the center of the pool, another opening goes on another 10 feet or so. No matter how hard you try, you can’t see the bottom of that opening because it’s a void, and the void is a symbol of the emptiness that we feel here over the loss of life. I’m sure all of you can see the water under the names. That water comes directly from the pool. What someone will do, visiting a loved one — and please feel free to do the very, very same — take their hand, put it in the water, rub their hand over a name. Water, of course, a symbol of life. And notice how the names are on the wall. They are not arranged in alphabetical order. For example, people who worked in the same office in this building, they’re together. Firefighters out on the same firehouse, together. Police officers out of the same police precinct, together. We call that meaningful adjacencies. People together in death just the way they were together in life. I have a stupid question. The names of the killers. Are they — Absolutely not. Not. Absolutely not. Yeah. The only place you’ll find them is if you should go into the museum, there’s a special part that deals with Al Qaeda. [somber music playing] [water cascading] [somber music playing]

To learn more about the 9/11 Memorial in New York City, students can watch the above 18-minute video from our Film Club series. Then, they can respond to the questions below in writing or discussion.

What moments in this film stood out for you? Why?

Were there any surprises? Anything that challenged what you know — or thought you knew?

What messages, emotions or ideas will you take away from this film? Why?

What connections can you make between this film and your own life or experience? Why? Does this film remind you of anything else you’ve read or seen? If so, how and why?

Then, students can read a 2019 article about the opening of the 9/11 Memorial Glade in Lower Manhattan — a memorial for people, largely rescue and recovery workers, whose illnesses and deaths came years after Sept. 11, 2001.

After watching the video and reading the article, students can reflect on the following questions in a class discussion:

Why do we memorialize people or events? What purpose should a memorial serve?

What purpose does memorializing Sept. 11 serve? How do you think Sept. 11 can be most effectively or meaningfully memorialized?

What concerns or challenges should societies or organizations be mindful of when they create memorials? Why?

If you’re interested in furthering the conversation about the memorial in your class, the 9/11 Memorial and Museum has a collection of resources for teachers and students.

7. Evaluate International Repercussions

How the u.s. military response to the 9/11 attacks led to decades of war., officials who drove the decades-long war in afghanistan look back on the strategic mistakes and misjudgments that led to a 20-year quagmire..

Two decades after invading Afghanistan, the United States is withdrawing, leaving chaos in its wake and the country much as it found it 20 years ago. “The Taliban don’t just control Kabul, but the whole country.” How did a war that began in response to the 9/11 attacks become the longest in American history? “If somebody had told me in 2001 that we were going to be there for another 20 years, I would not have believed them.” And what lessons can be learned for the future? “We were doing the same thing year after year after year, expecting a different result.” “Nearly 2,400 Americans have died in Afghanistan.” “More than 43,000 Afghan civilians lost their lives.” “You can’t remake a country on the American image. You can’t win if you’re fighting people who are fighting for their own villages and their own territory. Those were lessons we thought we learned in Vietnam. And yet, 30, 40 years later, we end up in Afghanistan, repeating the same mistakes.” On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, President George W. Bush was visiting an elementary school in Sarasota, Fla., when he received word of an attack on the World Trade Center in New York City. “We’re looking at a live picture of the, of the building right now. And, uh, what would you say? That would be about the 90th floor or so?” The president joined his staff in an empty classroom, where his C.I.A. intelligence briefer, Michael Morell, had been watching the attack unfold. “There was a TV there and the second plane hit.” “Oh my goodness.” “Oh God.” “There’s another one.” “Oh.” “Oh my goodness, there’s another one.” “God.” “And when that happened, I knew that this was an act of terrorism.” At the Capitol in Washington, Representative Barbara Lee’s meeting was interrupted. “I heard a lot of noise saying, ‘Evacuate. Leave. Get out of here. Run fast.’ So, I ran up Independence Avenue. As I turned around, I was able to see a heck of a lot of smoke.” “Another aircraft, unbelievably, has crashed into the Pentagon.” “What you have to understand is this is the largest attack ever in the entire history of the country.” At 9:59 a.m., the second World Trade Center tower to be struck collapsed. Twenty-nine minutes later, the other tower followed. “The president, he asked to see me in his office on Air Force One. The president looked me in the eye and he said, ‘Michael, who did this?’ I told the president that I would bet my children’s future that Al Qaeda was responsible for this attack.” Within hours, evidence surfaced that Al Qaeda, a multinational terrorist organization headed by the Islamic fundamentalist Osama Bin Laden, had committed the attacks. The group was being given safe haven in Afghanistan by the Taliban regime. “The president’s inclination was to hit back and hit back hard.” “I can hear you. The rest of the world hears you. And the people — ” “So the president decided to go to war.” “ — And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.” “We had to go to Afghanistan. There’s no question in any of our minds, it’s a war of necessity. We had to go after Al Qaeda, we had to kill them, we had to get them out, and we had to pursue them to the ends of the earth.” “The word on the street was everyone’s got to be united with the president. You know, the country is in mourning.” Three days after the attacks, Lee was under pressure to vote yes on a resolution in Congress to authorize going to war against Al Qaeda and its allies when she heard a eulogy at a memorial service. “That as we act, we not become the evil we deplore.” “It was at that point I said, We need to think through our military response, our national security response and the possible impact on civilians.” “Mr. Speaker, members, I rise today really with a very heavy heart. One that is filled with sorrow for the families and the loved ones who were killed and injured this week. Yet I am convinced that military action will not prevent further acts of international terrorism against the United States.” “Got back to the office and all hell was breaking loose.” “The only dissenting voice was Democrat Barbara Lee of California, voting no.” “Phone calls, threats. People were calling me a traitor. She’s got to go. But I knew then it was going to set the stage for perpetual war.” Within weeks of 9/11, the U.S. struck back in Afghanistan. “The United States military has begun strikes against Al Qaeda terrorist training camps and military installations of the Taliban regime.” Soon after, U.S. ground troops arrived in the country. “The invasion was a success very quickly.” “At the gates of Kabul, news of a Taliban collapse had already reached these thousands.” “The Taliban retreat has turned into a rout.” “By the end of the year, the Taliban had been driven from power. A large number of Al Qaeda operatives had either been killed or captured.” And although Osama Bin Laden had managed to escape, the U.S. had accomplished its main goal. “Al Qaeda could not operate out of Afghanistan anymore.” President Bush knew there was a history of failed military campaigns in Afghanistan. “We know this from not only intelligence but from the history of military conflict in Afghanistan. It’s been one of initial success followed by long years of floundering and ultimate failure. We’re not going to repeat that mistake.” [Applause] But after his initial success, Bush expanded the mission to nation-building. To prevent further Al Qaeda attacks, his administration said it wanted to transform the poor, war-torn country into a stable democracy, with a strong central government and U.S.-trained military. “The idea was it would be impossible for the Taliban to ever return to power and impossible for Afghanistan to ever be used as a safe haven again.” “There were girls starting to go to school, there were clinics and hospitals being set up, there were vaccinations, there were elections planned. Everything was kind of humming along and we all thought, OK, this is going to be fine.” But by the mid-2000s, after the Bush administration expanded the war on terror to Iraq, Richard Boucher realized that the U.S.-backed Afghan government was plagued by corruption and mismanagement. “I used to say to my guys on the Afghan desk, ‘If we’re winning, how come it don’t look like we’re winning?’” “The Taliban have staged a major comeback, seizing control of large swaths of the country.” “The people were not rejecting the Taliban. And that was, in the end, because the government couldn’t deliver much for the people. Everybody had this idea in their heads that government works the way it does in Washington. But Afghanistan hasn’t worked that way in the past. I think that was a moment we should’ve at least asked ourselves whether it wasn’t really time for us to leave and to say to the Afghans, ‘It’s your place, you run it as best you can.’” Instead, by 2011, President Bush’s successor, Barack Obama, had sent nearly 50,000 more troops to Afghanistan, hoping to reverse the Taliban’s gains. “I think one of the biggest mistakes we made strategically, after 9/11, was to fail to finish the job here, focus our attention here. We got distracted by Iraq.” One of those troops was Marine Captain Timothy Kudo. Part of his job was to shore up support for the government by digging wells and building schools. He soon lost faith in that mission after, he says, his company killed two Afghan teenagers they mistakenly believed were firing on them. “And their family saw this happen. The mothers, the grandmothers, they came out. It was the first time I’d ever seen an Afghan woman without wearing a burqa. They were sobbing and crying uncontrollably. I mean, how can you kill two innocent people and expect anything that you say to matter at that point?” “People here have little faith in U.S. forces anymore. More Afghans now blame the violence here on the U.S. than on the Taliban.” Weeks after Kudo returned home from Afghanistan, there was a monumental development. “I started getting all these texts, like, ‘You’ve got to check out the TV.’ My roommate calls me from the other room. ‘Turn on CNN.’” “The United States has conducted an operation that killed Osama Bin Laden, the leader of Al Qaeda.” “U.S.A.! U.S.A.!” “In that moment, people are celebrating in front of the White House. They’re celebrating by Ground Zero.” “This is where it happened. We’re back. It’s justice!” “And to my mind, there’s no more reason to go through this madness. And, of course, we then did it for another decade.” “I think the military and the national security apparatus thought they could win. And I think that they also wanted to believe that because they had invested so much. People had died and they didn’t want them to die in vain.” “2011, Bin Laden is now dead. Why was it so hard to de-escalate?” Jeffrey Eggers was on President Obama’s National Security Council. He says that the goal since 9/11, to make sure Afghanistan would never again be a safe haven for terrorists, had become a recipe for endless war. “We will forever prevent the conditions that led to such an attack.” “Danger close!” [Gunfire] “And if you define it that way, when are you finished?” [Gunfire] “Go! Come on, come on, come on!” Though the surge failed to push back the Taliban, the U.S. drew down troop levels even as doubts were growing that Afghan forces would be able to defend the country. In 2021, President Biden, the fourth president to preside over the war, announced that he would withdraw U.S. troops, a plan set in motion by his predecessor, Donald Trump. “Nobody should have any doubts. We lost the war in Afghanistan.” “And we’re clear to cross?” “It wasn’t a peace agreement; it was a withdrawal agreement. The agreement was essentially, As we withdraw, don’t attack us.” As the U.S. leaves Afghanistan, the Taliban is taking over again, having quickly overrun the Afghan Army, which the U.S. spent more than $80 billion to train and equip. “The Taliban are out in full force. And their Islamist rule is already coming back.” “They can use this as a recruiting tool. They are now the champions of the jihadi movement because they pushed out the United States.” And U.S. officials are reflecting on the beginning of the war, 20 years after 9/11. “More people should have thought about endless war, not just in Congress but in the State Department, in the Defense Department, C.I.A. and elsewhere, in the White House. That the recipe of using military means to go after terrorism was just going to get us into one fight after another after another. One can only hope that Americans of the new generation will think about this.”

In an address to Congress and the nation on Sept. 20, 2001, President George W. Bush made it clear that the response to the terrorist attacks would not be confined to a single military strike on one group, network or country: “Our war on terror begins with Al Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated.”

Help students uncover the motivation behind the attacks and evaluate the international repercussions of the “war on terror” using the following resources:

The Terrorist Attack : Who was responsible for the attacks on Sept. 11? Why did they target the United States, and particularly civilians? Britannica and USA Today each offer brief summaries of the plot and the roles of Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden. To go more in depth, you might have students watch the three-part documentary series “ Road to 9/11 ” from the History Channel, which provides a 360-degree overview of events that led to the attack.

To help students understand why the World Trade Center, Pentagon and U.S. Capitol were targeted, see the 9/11 Memorial and Museum lesson plan, “ Targeting American Symbols .”

The U.S. Response and the Global “War on Terror”: On Oct. 7, 2001, just weeks after the attacks, Mr. Bush announced that America had started a bombing campaign against Al Qaeda, the group responsible for the attacks, and the Taliban, the group that harbored them in Afghanistan.

So began the longest war in American history, which ended this year with the removal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan. What did the war accomplish? Use our Lesson of the Day on “ The U.S. War in Afghanistan: How It Started, and How It Ended ” to have students evaluate the causes and consequences of the 20-year conflict. They can also watch the 10-minute RetroReport video (embedded above), which looks at the decisions that shaped the war. And, they can use our Lesson of the Day “ What Will Become of Afghanistan’s Post-9/11 Generation? ” about how the lives of young people in Afghanistan have suddenly changed with the withdrawal of U.S. forces.

Beyond The Times, see the five-part lesson plan “ The Costs of War ,” created by the Choices Program, which examines the human, economic, social and political costs of the “war on terror” through videos and class discussions.

Veterans of the War in Afghanistan: Listen to voices of veterans in The Argument podcast episode “ You Don’t Bring Democracy at the Point of a Gun ” or read about their experiences in the essay “ Serving in a Twenty Year War .” How do these firsthand accounts and perspectives change how students understand the realities of the so-called war on terror? What questions would they ask these veterans if they were New York Times reporters?

After exploring one or more of the pieces in this section, students might discuss the prompts below:

What is terrorism? Why do some individuals and groups target civilians for political purposes?

Was the United States justified in using military force in Afghanistan after Sept. 11? What is the legacy of the “war on terror”? Has it made us safer?

What lessons can we learn from the war? How do you think the United States and other countries should work toward preventing future terrorist attacks? If the United States, or another country, were hit by foreign terrorism again in the future, how should we respond? What principles, critical questions and experiences should help us form our response?

8. Examine Ripple Effects in the United States

In the two decades since Sept. 11, many aspects of American life have changed, from travel and art to education and immigration . Your conversation with students about post-9/11 America could take on any one or many of these topics. Below, we suggest two possible lenses, based on recent Times texts, through which to examine the ripple effects in the United States:

Muslims in America : Invite students to read “ Muslim Americans’ ‘Seismic Change’ ” by Elizabeth Dias and consider how the aftermath of Sept. 11 has brought both challenges, including a surge in Islamophobia, but also possibilities for the Muslim American community, such as the election of Muslim Americans to Congress and award-winning television featuring Muslim American actors and stories, that would have been unfathomable 20 years ago.

Civil Liberties and Surveillance: Two decades after the attacks, police departments across the United States, and particularly the N.Y.P.D., are using counterterrorism tools, like facial recognition software, to combat routine street crime. Although police officials say these methods have helped thwart would-be attacks, others say they subject everyday people to “near-constant surveillance — a burden that falls more heavily on people of color.” Invite students to read “ How the N.Y.P.D. Is Using Post-9/11 Tools on Everyday New Yorkers ” and debate the benefits and drawbacks of these tactics.

After reading one or both of these articles, students might discuss the following questions:

In what important ways has Sept. 11 transformed American life?

Did anything described in the articles connect with anything you’ve experienced, read or witnessed? How have these changes affected your life, whether you knew it or not?

What does America’s response to Sept. 11 say about the United States today?

9. Explore Why Conspiracy Theories Sometimes Flourish

Today’s students are often familiar with conspiracy theories and their popularity on social media. Here is how one student responded to our 2020 Student Opinion question: Do You Think Online Conspiracy Theories Can Be Dangerous? :

Conspiracy theories can either be malicious, dumb fun, or anything in between. Some conspiracy theories can be serious and about tragedies such as 9/11, but some conspiracy theories can be interesting, such as bots in a video game being alive. I enjoy a conspiracy theory every now or then, but I wouldn’t take them as an absolute truth, you always have to take them with a grain of salt.

In the article “ How a Viral Video Bent Reality ,” Kevin Roose writes about how the conspiracy film “Loose Change” energized the “9/11 truther” movement and also supplied the template for the current age of disinformation.

Students can read this article and consider some of the questions raised in the article:

Why do you think some people are drawn to conspiracy theories?

What role does technology play in the spread of conspiracy theories?

Respond to this quote from the article: “A more urgent lesson to take from ‘Loose Change’ is that conspiracy theories tend to flourish in low-trust environments, during periods of change and confusion.” Why do you think that is? How does that lesson apply to today’s world?

You can pair this article with the Student Opinion question mentioned above, inviting students to post their own comments in response to that question, or with our Lesson of the Day “How to Deal With a Crisis of Misinformation,” which includes strategies for countering misinformation.

10. Watch Our On-Demand Panel for Students: The Post-9/11 Generation

How did 9/11 shape the generation that grew up in its aftermath?

With New York Times journalists and student voices, we discuss this question in our special interactive panel. The panel features Yousur Al-Hlou and Biz Herman, who examined how Sept. 11 has been taught in classrooms around the world, and Kiana Hayeri, who photographed young Afghans as they experienced the recent withdrawal of U.S. troops from their country. Invite students to register and view the on-demand panel .

Want more? For the 10th anniversary of Sept. 11, in 2011, we published this roundup of hundreds of resources from The Learning Network and The New York Times for teaching about Sept. 11 and the aftermath, including ideas from educators across the country and links to the front pages of The Times for the 10 days after Sept. 11.

Nicole Daniels has been a staff editor with The Learning Network since 2019. More about Nicole Daniels

Twenty years later, how Americans assess the effects of the 9/11 attacks

Subscribe to governance weekly, william a. galston william a. galston ezra k. zilkha chair and senior fellow - governance studies.

September 9, 2021

There is no evidence that this sentiment has faded during the past five years. A survey released earlier this month found 64% of Americans—the highest share ever—said that 9/11 has permanently changed the way we live our lives. Significant minorities are less willing to take flights, go into skyscrapers, attend mass events, or travel overseas than they were before 9/11.

Many Americans’ views of Islam have also undergone long-term change. In March of 2002, 25% of Americans, including 23% of Democrats and 32% of Republicans, believed that Islam is more likely to encourage violence among its followers than are other religions. Today, the share of Americans endorsing this view has doubled to 50%, but unlike two decades ago, it has divided the parties. Seventy-two percent of Republicans (up 40 points since 2002) now see an intense link between Islam and violence, compared with 32% of Democrats. These sentiments go a long way toward explaining why Donald Trump’s mistrust of Muslims played so well among his supporters—and why so many Democrats reacted with fury to Mr. Trump’s restrictions on travel from Muslim countries early in his administration.

Under George W. Bush’s leadership, the United States responded to the 9/11 attacks by launching a “war on terror,” beginning in Afghanistan, where al-Qaeda’s plot was conceived and organized. While this military venture and the subsequent invasion of Afghanistan initially enjoyed strong public backing, support eroded as the wars on the ground went on longer than expected. After the killing of Osama bin Laden in 2011, 56% of Americans said they now supported withdrawing our troops from Afghanistan.

It took another decade, spanning three presidents, to honor their wishes. No wonder the phrase “endless wars” became commonplace across party lines. And the way the war in Afghanistan finally ended intensified public discontent. Seven in ten Americans believe that we failed to achieve our goals in Afghanistan—a somewhat smaller majority says the same about the invasion of Iraq. Only 8% of Americans say that the withdrawal from Afghanistan has made us safer from terrorism, compared to 44% who say that it has made us less safe. We will never know whether Americans would have a more optimistic assessment if the withdrawal had been less abrupt and better organized.