Critical Thinking vs. Reflective Thinking

What's the difference.

Critical thinking and reflective thinking are both important cognitive processes that involve analyzing and evaluating information. However, critical thinking tends to focus more on questioning and challenging assumptions, beliefs, and arguments, while reflective thinking involves looking back on past experiences and considering how they have shaped one's beliefs and actions. Critical thinking is often used to solve problems and make decisions, while reflective thinking is more about self-awareness and personal growth. Both types of thinking are essential for developing a deeper understanding of complex issues and making informed choices.

| Attribute | Critical Thinking | Reflective Thinking |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgment | Process of analyzing and making sense of information and experiences |

| Goal | To make reasoned judgments | To gain deeper understanding and insight |

| Approach | Logical and analytical | Contemplative and introspective |

| Focus | On evaluating arguments and evidence | On personal experiences and emotions |

| Application | Used in problem-solving and decision-making | Used in personal growth and self-improvement |

Further Detail

Introduction.

Critical thinking and reflective thinking are two important cognitive processes that play a crucial role in problem-solving, decision-making, and learning. While they share some similarities, they also have distinct attributes that set them apart. In this article, we will explore the key characteristics of critical thinking and reflective thinking, and discuss how they differ in their approaches and outcomes.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a systematic way of thinking that involves analyzing and evaluating information, arguments, and evidence in order to make informed decisions or judgments. It requires individuals to question assumptions, consider multiple perspectives, and apply logical reasoning to arrive at well-reasoned conclusions. Critical thinking is often associated with skills such as analysis, evaluation, interpretation, and inference.

- Critical thinking involves being open-minded and willing to consider alternative viewpoints.

- It requires individuals to be skeptical and not accept information at face value.

- Critical thinking involves asking probing questions to clarify and deepen understanding.

- It focuses on evidence-based reasoning and logical thinking.

- Critical thinking is essential for problem-solving and decision-making in complex situations.

Reflective Thinking

Reflective thinking, on the other hand, is a process of introspection and self-examination that involves looking back on past experiences, actions, or decisions in order to learn from them and improve future outcomes. It requires individuals to engage in self-awareness, self-assessment, and self-regulation to gain insights into their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Reflective thinking is often associated with skills such as self-reflection, self-awareness, self-evaluation, and self-improvement.

- Reflective thinking involves examining one's own beliefs, values, and assumptions.

- It requires individuals to consider how their actions and decisions impact themselves and others.

- Reflective thinking involves identifying strengths and weaknesses in one's thinking and behavior.

- It focuses on personal growth, learning, and development.

- Reflective thinking is essential for self-improvement and continuous learning.

While critical thinking and reflective thinking share the common goal of improving cognitive processes and decision-making, they differ in their approaches and outcomes. Critical thinking is more focused on analyzing and evaluating external information and arguments, while reflective thinking is more focused on examining internal thoughts and experiences. Critical thinking emphasizes logical reasoning and evidence-based thinking, while reflective thinking emphasizes self-awareness and personal growth.

Both critical thinking and reflective thinking are essential skills that can complement each other in the learning process. Critical thinking can help individuals make informed decisions based on evidence and reasoning, while reflective thinking can help individuals gain insights into their own thoughts and behaviors to improve their decision-making processes. By combining critical thinking and reflective thinking, individuals can enhance their problem-solving abilities and make more effective decisions in various contexts.

In conclusion, critical thinking and reflective thinking are two important cognitive processes that play a crucial role in problem-solving, decision-making, and learning. While critical thinking focuses on analyzing and evaluating external information and arguments, reflective thinking focuses on examining internal thoughts and experiences. Both critical thinking and reflective thinking are essential skills that can complement each other in the learning process and help individuals improve their decision-making processes. By developing both critical thinking and reflective thinking skills, individuals can enhance their cognitive abilities and make more informed and effective decisions in various contexts.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Home » General » What is the Difference Between Critical Thinking and Reflective Thinking

What is the Difference Between Critical Thinking and Reflective Thinking

The main difference between critical thinking and reflective thinking is that critical thinking is the ability to think in an organized and rational manner , understanding the logical connection between ideas or facts, whereas reflective thinking is the process of reflecting on one’s emotions, feelings , experiences, reactions, and knowledge, creating connections between them.

Critical thinking and reflective thinking are necessary for analyzing facts and investigating a matter rationally. These two terms are often used interchangeably. However, reflective thinking is a part of critical thinking.

Key Areas Covered

1. What is Reflective Thinking – Definition, Features 2. What is Critical Thinking – Definition, Features 3. Difference Between Critical Thinking and Reflective Thinking – Comparison of Key Differences

What is Reflective Thinking

Reflective thinking is the process of reflecting on one’s emotions, feelings, experiences, reactions, and knowledge, creating connections between them, which leads to learning. In reflective thinking, you have to consciously think about and analyze what you are doing now, what you have done previously, what you have experienced, what you have learned, and how you have learned it. We can also describe reflective thinking as awareness our awareness of our knowledge, assumptions, and past experiences. It’s our past experiences and learning that make the context of our thoughts. Therefore, these are unique to us. Furthermore, reflective learning is an active and dynamic process that keeps on developing and evolving as we learn and respond to new experiences, situations, and information.

In reflective thinking, we interpret and evaluate our experiences, derive meaning from them, and use them for problem-solving. It also involves analyzing and critiquing. In this context, analyzing involves breaking complex topics into smaller sections to understand them better, while critiquing involves questioning our assumptions and understanding.

What is Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is our ability to think in an organized and rational manner, understanding the logical connection between ideas or facts. This involves rational and unbiased analysis or evaluation of factual evidence. It’s also important to note that a person with critical thinking skills will always engage in reflective and independent thinking. They will always question ideas and assumptions and analyze them critically without accepting them at face value. They also identify, analyze, solve problems systematically, instead of by instinct or intuition .

Critical thinking involves a process with several steps. The first step is identifying the problem or question. Once you narrow it down, it’s easier to find solutions. Then find sources that give different ideas and points of view relevant to this issue. Next, analyze and evaluate the data you have found. Now it’s important to determine whether these sources are reliable, unbiased and whether they are based on strong data. After a good analysis, you can establish what sources are most important. Then you can make a decision or reach a conclusion based on this data.

Difference Between Critical Thinking and Reflective Thinking

Critical thinking is the ability to think in an organized and rational manner, understanding the logical connection between ideas or facts, whereas reflective thinking is the process of reflecting on one’s emotions, feelings, experiences, reactions, and knowledge, creating connections between them.

Moreover, critical thinking involves a wide range of thinking skills, and reflective thinking is a part of critical thinking.

In brief, critical thinking involves thinking in an organized and rational manner, understanding the logical connection between ideas or facts. Reflective thinking, on the other hand, involves reflecting on one’s emotions, feelings, experiences, reactions, and knowledge, creating connections between them. Thus, this is the main difference between critical thinking and reflective thinking. Moreover, critical thinking involves a wide range of thinking skills, and reflective thinking is a part of critical thinking.

1.“ What Is Reflective Thinking? ” OpenLearn.

Image Courtesy:

1. “ Reflective Thinking ” By Irisyu160 – Own work (CC BY-SA 4.0) via Commons Wikimedia 2. “ 170623. CRITICAL THINKING ” By Engage Visually. Debbie Ro (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) via Flickr

About the Author: Hasa

Hasanthi is a seasoned content writer and editor with over 8 years of experience. Armed with a BA degree in English and a knack for digital marketing, she explores her passions for literature, history, culture, and food through her engaging and informative writing.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

- Create account

- Beginner Spanish

- Intermediate Spanish

- Administrators

- Sube Method

- Sube Online

Try the Sube Kit Risk Free with Our 30 Day Money Back Guarantee

Reflective Thinking vs. Critical Thinking - What's the Difference?

March 28, 2013

Sometimes a simple internet search of a term that I am using repeatedly in my work can lead to new insights. During a lively conversation with friends analyzing the challenges of teaching and learning a language, we talked about the need to shift from memorizing and rote learning to reflective thinking and critical thinking. In the dialogue, the question came up of whether reflective thinking in the U.S. culture manifests differently than reflecting thinking in Asia, and we started questioning our own definitions of reflective and critical thinking. So I looked up some definitions. Below is my favorite posted on the University of Hawaii website, and including some classroom tips. I think the definitions are a great resource in themselves. Gets you thinking! What is reflective thinking?

• The description of reflective thinking: Critical thinking and reflective thinking are often used synonymously. Critical thinking is used to describe: "... the use of those cognitive skills or strategies that increase the probability of a desirable outcome...thinking that is purposeful, reasoned and goal directed - the kind of thinking involved in solving problems, formulating inferences, calculating likelihoods, and making decisions when the thinker is using skills that are thoughtful and effective for the particular context and type of thinking task. Critical thinking is sometimes called directed thinking because it focuses on a desired outcome." Halpern (1996).

Reflective thinking, on the other hand, is a part of the critical thinking process referring specifically to the processes of analyzing and making judgments about what has happened. Dewey (1933) suggests that reflective thinking is an active, persistent, and careful consideration of a belief or supposed form of knowledge, of the grounds that support that knowledge, and the further conclusions to which that knowledge leads. Learners are aware of and control their learning by actively participating in reflective thinking – assessing what they know, what they need to know, and how they bridge that gap – during learning situations.

In summary, critical thinking involves a wide range of thinking skills leading toward desirable outcomes and reflective thinking focuses on the process of making judgments about what has happened. However, reflective thinking is most important in prompting learning during complex problem-solving situations because it provides students with an opportunity to step back and think about how they actually solve problems and how a particular set of problem solving strategies is appropriated for achieving their goal. Characteristics of environments and activities that prompt and support reflective thinking:

http://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Reflective_thinking

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_thinking

← Older Post Newer Post →

Leave a comment

Please note, comments must be approved before they are published

Critical Thinking and Reflective Thinking

Critical and Reflective Thinking encompasses a set of abilities that students use to examine their own thinking and that of others. This involves making judgments based on reasoning, where students consider options, analyze options using specific criteria, and draw conclusions.

People who think critically and reflectively are analytical and investigative, willing to question and challenge their own thoughts, ideas, and assumptions and challenge those of others. They reflect on the information they receive through observation, experience, and other forms of communication to solve problems, design products, understand events, and address issues. A critical thinker uses their ideas, experiences, and reflections to set goals, make judgments, and refine their thinking.

- Back to Thinking

- Connections

- Illustrations

Analyzing and critiquing

Students learn to analyze and make judgments about a work, a position, a process, a performance, or another product or act. They reflect to consider purpose and perspectives, pinpoint evidence, use explicit or implicit criteria, make defensible judgments or assessments, and draw conclusions. Students have opportunities for analysis and critique through engagement in formal tasks, informal tasks, and ongoing activities.

Questioning and investigating

Students learn to engage in inquiry when they identify and investigate questions, challenges, key issues, or problematic situations in their studies, lives, and communities and in the media. They develop and refine questions; create and carry out plans; gather, interpret, and synthesize information and evidence; and reflect to draw reasoned conclusions. Critical thinking activities may focus on one part of the process, such as questioning, and reach a simple conclusion, while others may involve more complex inquiry requiring extensive thought and reflection.

Designing and developing

Students think critically to develop ideas. Their ideas may lead to the designing of products or methods or the development of performances and representations in response to problems, events, issues, and needs. They work with clear purpose and consider the potential uses or audiences of their work. They explore possibilities, develop and reflect on processes, monitor progress, and adjust procedures in light of criteria and feedback.

Reflecting and assessing

Students apply critical, metacognitive, and reflective thinking in given situations, and relate this thinking to other experiences, using this process to identify ways to improve or adapt their approach to learning. They reflect on and assess their experiences, thinking, learning processes, work, and progress in relation to their purposes. Students give, receive, and act on feedback and set goals individually and collaboratively. They determine the extent to which they have met their goals and can set new ones.

I can explore.

I can explore materials and actions. I can show whether I like something or not.

I can use evidence to make simple judgments.

I can ask questions, make predictions, and use my senses to gather information. I can explore with a purpose in mind and use what I learn. I can tell or show others something about my thinking. I can contribute to and use simple criteria. I can find some evidence and make judgments. I can reflect on my work and experiences and tell others about something I learned.

I can ask questions and consider options. I can use my observations, experience, and imagination to draw conclusions and make judgments.

I can ask open-ended questions, explore, and gather information. I experiment purposefully to develop options. I can contribute to and use criteria. I use observation, experience, and imagination to draw conclusions, make judgments, and ask new questions. I can describe my thinking and how it is changing. I can establish goals individually and with others. I can connect my learning with my experiences, efforts, and goals. I give and receive constructive feedback.

I can gather and combine new evidence with what I already know to develop reasoned conclusions, judgments, or plans.

I can use what I know and observe to identify problems and ask questions. I explore and engage with materials and sources. I can develop or adapt criteria, check information, assess my thinking, and develop reasoned conclusions, judgments, or plans. I consider more than one way to proceed and make choices based on my reasoning and what I am trying to do. I can assess my own efforts and experiences and identify new goals. I give, receive, and act on constructive feedback.

I can evaluate and use well-chosen evidence to develop interpretations; identify alternatives, perspectives, and implications; and make judgments. I can examine and adjust my thinking.

I can ask questions and offer judgments, conclusions, and interpretations supported by evidence I or others have gathered. I am flexible and open-minded; I can explain more than one perspective and consider implications. I can gather, select, evaluate, and synthesize information. I consider alternative approaches and make strategic choices. I take risks and recognize that I may not be immediately successful. I examine my thinking, seek feedback, reassess my work, and adjust. I represent my learning and my goals and connect these with my previous experiences. I accept constructive feedback and use it to move forward.

I can examine evidence from various perspectives to analyze and make well-supported judgments about and interpretations of complex issues.

I can determine my own framework and criteria for tasks that involve critical thinking. I can compile evidence and draw reasoned conclusions. I consider perspectives that do not fit with my understandings. I am open-minded and patient, taking the time to explore, discover, and understand. I make choices that will help me create my intended impact on an audience or situation. I can place my work and that of others in a broader context. I can connect the results of my inquiries and analyses with action. I can articulate a keen awareness of my strengths, my aspirations and how my experiences and contexts affect my frameworks and criteria. I can offer detailed analysis, using specific terminology, of my progress, work, and goals.

The Core Competencies relate to each other and with every aspect of learning.

Connections among Core Competencies

The Core Competencies are interrelated and interdependent. Taken together, the competencies are foundational to every aspect of learning. Communicating is intertwined with the other Core Competencies.

Critical and Reflective Thinking is one of the Thinking Core Competency’s two interrelated sub-competencies, Creative Thinking and Critical and Reflective Thinking.

Critical and Reflective Thinking and Creative Thinking overlap. For example:

- Students use creative thinking to generate new ideas when solving problems and addressing constraints that arise as they question and investigate, and design and develop

- Students use critical thinking to analyze and reflect on creative ideas to determine whether they have value and should be developed, engaging in ongoing reflection as they develop their creative ideas

Communication

Critical and Reflective Thinking is closely related to the two Communication sub-competencies: Communicating and Collaborating. For example:

- Students apply critical thinking to acquire and interpret information, and to make choices about how to communicate their ideas

- Students often collaborate as they work in groups to analyze and critique, and design and develop

Personal and Social

Critical and Reflective Thinking is closely related to the three Personal and Social sub-competencies, Personal Awareness and Responsibility, Social Awareness and Responsibility, and Positive Personal and Cultural Identity. For example:

- Students think critically to determine their personal and social responsibilities

- Students apply their personal awareness as they reflect on their efforts and goals

Connections with areas of learning

Critical and Reflective Thinking is embedded within the curricular competencies of the concept-based, competency-driven curriculum. Curricular competencies are focused on the “doing” within the area of learning and include skills, processes, and habits of mind required by the discipline. For example, the Critical and Reflective Thinking sub-competency can be seen in the sample inquiry questions that elaborate on the following Big Ideas in Science:

- Light and sound can be produced and their properties can be changed: How can you explore the properties of light and sound? What discoveries did you make? (Science 1)

- Matter has mass, takes up space, and can change phase: How can you explore the phases of matter? How does matter change phases? How does heating and cooling affect phase changes? (Science 4)

- Elements consist of one type of atom, and compounds consist of atoms of different elements chemically combined: What are the similarities and differences elements and compounds? How can you investigate the properties of elements and compounds? (Science 7)

- The formation of the universe can be explained by the big bang theory: How could you model the formation of the universe? (Science 10)

| Title | Sub-competencies | |

|---|---|---|

| Les élèves participent à une simulation de débat de l’ONU sur le contrôle des armes à feu aux États Unis en tenant compte du point de vue de divers États. | , | |

| Les élèves utilisent le matériel de classe pour concevoir des habitats qui procurent aux animaux ce dont ils ont besoin pour survivre. | , , | |

Une élève, inspirée par un roman sur l’expérience d’une jeune fille dans un pensionnat indien, rassemble de plus amples renseignements et, quatre ans plus tard, organise une Journée du chandail orange dans son école. | , , | |

| Un élève explore des possibilités de carrières. | , | |

Une élève a enquêté sur la façon dont les artistes s’expriment et a créé une œuvre authentique. | , , | |

Un élève fait une réflexion approfondie sur ses expériences d’apprentissage comme examen final d’un programme STIM (sciences, technologie, ingénierie, mathématiques). | , , | |

| Un élève est amené à réfléchir spontanément à son point de vue sur l’itinérance et la pauvreté après avoir fait du bénévolat à une mission urbaine. | ||

| On a demandé aux élèves d’interviewer des « personnes d’âge mûr de la collectivité », et l’élève a choisi d’interviewer un voisin de longue date. | , , | |

| Les élèves font des recherches sur les phobies pour les distinguer de la peur, puis réfléchissent et discutent des réactions aux questions d’orientation sexuelle et d’identité de genre. | , , | |

| Les élèves ont étudié la question de ce qu’est une famille et ont réfléchi à leur propre famille. | , , | |

| Des élèves conçoivent un logo pour des toilettes d’accès universel. | , , , | |

| Une élève participe à une discussion mathématique et réfléchit ensuite sur sa capacité à communiquer sa pensée pendant cette discussion. | , | |

Un élève construit une maquette d’aquarium qui garderait les poissons heureux et en santé. | , | |

Après avoir rencontré d’anciens combattants lors d’un événement du jour du Souvenir, un élève forme un groupe consacré aux liens intergénérationnels entre élèves et anciens combattants. | , , | |

Au fil du temps, l’élève réalise un ensemble d’œuvres créatives sur le thème de l’identité. | , , , | |

A student uses “loose parts” to record his observations of seasonal changes in the local environment. | , | |

A student explores magnetic properties using a magnetic wand. | ||

A student creates a presentation reflecting on their school experience and goals for the future. | , , , | |

A student explains how he learned to be persistent and why that trait is important to him. | , , | |

A student writes an essay in response to the prompt “How We Know Who We Are”. | , , , | |

Students present their application for the Mars One project, explaining how they would be suited to the project and how they would deal with issues they would likely face. | , , | |

A student reflects on the personal experiences that have changed his goals and aspirations. | , , , | |

During a portfolio review, students reflect on their writing, set goals, and create a plan for moving forward. | , | |

A student approaches a teacher with her concerns about her progress in math. | , | |

Students explore issues related to the manufacturing of jeans in sweatshops. | ||

After creating submersibles, students reflected on their creation process and the challenges they encountered. | , | |

Students create a mind map to assess and reflect on their learning. | , | |

A student shares his reasoning about which group of dinosaurs would win a battle. | ||

A student creates a one-page representation of the story “ | , | |

Students generate and develop a variety of ideas when challenged to see how high they can stack provided materials. | ||

Students work together to solve an open-ended problem about sharing cookies. | ||

As part of an engineering study, students work collaboratively to build, test, and adapt roller coasters. | ||

Students work in small groups to design an experiment that explores the effects of different salt solutions on gummy bears. | ||

| , | ||

A student applies what he knows about genetics to critique the movie "Gattaca". | , | |

A student develops, evaluates, and revises a process for calculating the area under a curve. | ||

A student uses her senses to explore a toy bear and rocks. | ||

Students create documentaries that explore the pros and cons of the Site C dam while considering the various stakeholders. | , | |

Students reflect on the process they used to make pinhole cameras and the variables that affected its effectiveness. | , | |

During an architecture project, a student uses found materials to represent that hotels simultaneously act as public space and private refuge. | , | |

A student designs a snake made of pull-tabs in response to a class challenge. | ||

A student extends a classroom assignment by designing a fire starter for campers. | , | |

A student works with classmates to build a cardboard vending machine to deliver secret Santa presents. | , | |

A student creates a political cartoon to encourage community members to support a ban of shark fin products. | , , | |

After doing a report on robots and assembling a robot from a kit, a student designs his own robot. | , | |

A student makes duct tape wallets as a hobby. | , | |

A group of students engage in a multi-stage design process to make a working model of a construction crane. | , | |

Students build mousetrap cars made from household materials and participated in a Mousetrap Car Competition. | ||

A student retells the story of the “Three Billy Goats Gruff” from the perspective of the troll while adding in a few twists. | , | |

Students work in groups on a problem-solving challenge called “Save Fred”. | , | |

Students make a hockey rink with whiteboards. | , | |

A student reflects on her performance singing a duet. | , , | |

Over time, a student develops a body of creative work exploring the theme of identity. | , , , | |

A student inquired into how artists express themselves, and produced an authentic piece of her own. | , , | |

Students investigated the question, “What is a family”, and reflected on their own families. | , , | |

Students were asked to interview an “older adult from the community” and this student chose to interview a long-time neighbour. | , , | |

Students research phobias to distinguish between phobias as fear and then discuss and reflect on reactions to SOGI. | , , | |

Students design a logo for a universal washroom. | , , , | |

Students participate in a Model UN debate on gun control in the United States by taking the perspectives of various states. | , | |

A student explores possible future careers. | , | |

Students collaboratively create ramps to explore the forces that effect motion. | , , | |

Students use classroom materials to design models of animal habitats that provide animals with what they need to survive. | , , | |

A student completes a comprehensive reflection of their learning experiences as a final exam in a STEM program. | , , | |

A student is moved to spontaneously reflect on his views on homelessness and poverty after volunteering at an urban mission. | ||

A student participates in a number talk and then reflects on her ability to communicate her thinking during these talks. | , | |

A student uses “loose parts” to record his observations of seasonal changes in the local environment. | , | |

A student builds a model of an aquarium that would keep fish happy and healthy. | , | |

A student, inspired by a novel about a girl’s residential school experience, gathers further information and, four years later, organizes an Orange Shirt Day at her school. | , , | |

After meeting veterans at a Remembrance Day event, a student forms a group dedicated to intergenerational connections between students and veterans. | , , |

Critical Thinking and Evaluating Information

- Introduction

- What Is Critical Thinking?

- Words Of Wisdom

Critical Thinking and Reflective Judgment

Stages of reflective judgment.

- Problem Solving Skills

- Critical Reading

- Critical Writing

- Use the CRAAP Test

- Evaluating Fake News

- Explore Different Viewpoints

- The Peer-Review Process

- Critical ThinkingTutorials

- Books on Critical Thinking

- Explore More With These Links

Live Chat with a Librarian 24/7

Text a Librarian at 912-600-2782

What is Reflective Judgment?

Critical thinking is "thinking about thinking." To apply critical thinking skills, skills to a particular problem implies a reflective sensibility and the capacity for reflective judgment (King & Kitchener, 1994). The simplest description of reflective judgment is that of ‘taking a step back.’ ( Dwyer, 2017)

Reflective judgment is the ability to evaluate and process information in order to draw plausible conclusions.

It can be defined more concisely in the video below:

Video Source and Credit: Bill Garris, Ph.D

| Stage | Developmental Period | View Of Knowledge | Concept of Justification | Statement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge exists absolutely and concretely. It can be obtained by direct observation. | No verification is needed. There are no alternate beliefs to be perceived | "I know what I have seen." |

| 2 | Pre-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is assumed to be absolutely certain or certain but not immediately available. Knowledge can be obtained directly through the senses (as in direct observation) or via authority figures. | Most issues are assumed to have a right answer, so there is little or no conflict in making decisions about disputed issues. | “If it is on the news, it has to be true.” |

| 3 | Pre-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is assumed to be absolutely certain or temporarily uncertain. In areas of temporary uncertainty, only personal beliefs can be known until absolute knowledge is obtained. In areas of absolute certainty, knowledge is obtained from authorities. | In areas in which certain answers exist, beliefs are justified by reference to authorities' views. In areas in which answers do not exist, beliefs are defended as personal opinions since the link between evidence and beliefs is unclear. | "When there is evidence that people can give to convince everybody one way or another, then it will be knowledge, until then, it's just a guess." |

| 4 | Quasi-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is uncertain and knowledge claims are idiosyncratic to the individual since situational variables (such as incorrect reporting of data, data lost over time, or disparities in access to information) dictate that knowing always involves an element of ambiguity. | Beliefs are justified by giving reasons and using evidence, but the arguments and choice of evidence are idiosyncratic (for example, choosing evidence that fits an established belief). | "I'd be more inclined to believe evolution if they had proof. It's just like the pyramids: I don't think we'll ever know. Who are you going to ask? No one was there." |

| 5 | Quasi-Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is contextual and subjective since it is filtered through a person's perceptions and criteria for judgment. Only interpretations of evidence, events, or issues may be known. | Beliefs are justified within a particular context by means of the rules of inquiry for that context and by the context-specific interpretations as evidence. Specific beliefs are assumed to be context specific or are balanced against other interpretations, which complicates (and sometimes delays) conclusions. | "People think differently and so they attack the problem differently. Other theories could be as true as my own, but based on different evidence." |

| 6 | Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is constructed into individual conclusions about ill-structured problems on the basis of information from a variety of sources. Interpretations that are based on evaluations of evidence across contexts and on the evaluated opinions of reputable others can be known. | Beliefs are justified by comparing evidence and opinion from different perspectives on an issue or across different contexts and by constructing solutions that are evaluated by criteria such as the weight of the evidence, the utility of the solution, and the pragmatic need for action. | "It's very difficult in this life to be sure. There are degrees of sureness. You come to a point at which you are sure enough for a personal stance on the issue." |

| 7 | Reflective Reasoning | Knowledge is the outcome of a process of reasonable inquiry in which solutions to ill-structured problems are constructed. The adequacy of those solutions is evaluated in terms of what is most reasonable or probable according to the current evidence, and it is reevaluated when relevant new evidence, perspectives, or tools of inquiry become available. | Beliefs are justified probabilistically on the basis of a variety of interpretive considerations, such as the weight of the evidence, the explanatory value of the interpretations, the risk of erroneous conclusions, the consequences of alternative judgments, and the interrelationships of these factors. Conclusions are defended as representing the most complete, plausible, or compelling understanding of an issue on the basis of the available evidence. | "One can judge an argument by how well thought-out the positions are, what kinds of reasoning and evidence are used to support it, and how consistent the way one argues on this topic is as compared with other topics." |

Source: King, P.M. & Kitchener, K.S. (1994). Developing Reflective Judgment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, pp. 14-16. Source hosted by Univerity of Michigan

- << Previous: What Is Critical Thinking?

- Next: Problem Solving Skills >>

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 8:18 AM

- URL: https://libguides.coastalpines.edu/thinkcritically

Module 5: Thinking and Analysis

Critical thinking, learning objectives.

- Define critical thinking

Thinking comes naturally. You don’t have to make it happen—it just does. But you can make it happen in different ways. For example, you can think positively or negatively. You can think with your heart and you can think with rational judgment. You can also think strategically and analytically, and mathematically and scientifically. These are a few of multiple ways in which the mind can process thought.

What are some forms of thinking you use? When do you use them and why?

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important thinking skills is critical thinking. Critical thinking is important because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It’s a “domain-general” thinking skill—not a thinking skill that’s reserved for a one subject alone or restricted to a particular subject area. Critical thinking is used in every domain, from physics to auto mechanics. It is often employed to problem solve when we are puzzled by something or to reveal that there is an error in common ways of thinking about things. Thus, critical thinking is essential for revealing biases.

For example, Galileo used a common form of reasoning called reductio ad absurdum (Latin for “reduce to absurdity) to show that the physics of his day was mistaken. People at that time believed that the heavier something was, the faster it would fall. Galileo knew this common conception was mistaken and he proved it both empirically and conceptually. Here is how he proved it conceptually. Suppose you have two objects, one heavier (call it B) than the other (call it A). Suppose the heavier object falls faster. When you put the lighter object under the heavier object (c), the lighter object should slow down the heavier object. On the other hand gluing together both objects results in a heavier object (c), which should fall even faster than (b). See diagram here . The contradiction proves by reductio ad absurdum that the assumption must be false. This is just one example, but the form of reasoning (reductio ad absurdum) is the same across every domain—from science to religion to auto mechanics. The form of reasoning is just this: assume for the sake of the argument that A is true. If we can then show that A leads to a contradiction (literally where two statements are asserted that cannot possibly be true), then we prove that A is false.

Great leaders have highly attuned critical thinking skills, and you can too. In fact, you probably have a lot of these skills already. Of all your thinking skills, critical thinking may have the greatest value.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. It means asking probing questions like, “How do we know?” or “Is this true in every case or just in this instance?” It involves being skeptical and challenging assumptions, rather than simply memorizing facts or blindly accepting what you hear or read.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why because you detect certain biases in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are other sides to the story.

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common? Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and they distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit.

This description may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop and finely tune your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and glean important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching. With critical thinking, you become a clearer thinker and problem solver.

| Critical Thinking IS | Critical Thinking Is NOT |

|---|---|

| Questioning | Memorizing |

| Examining assumptions | Blindly following what others around you think |

| Requiring evidence before you accept a claim | Blind acceptance of authority |

The following video from Lawrence Bland presents the major concepts and benefits of critical thinking.

You can view the transcript for “Critical Thinking.wmv” here (opens in new window) .

Supporting Claims with Evidence

Thinking and constructing analyses based on your thinking will bring you in contact with a great deal of information. Some of that information will be factual, and some will not be. You need to be able to distinguish between facts and opinions so you know how to support your arguments. Begin with the following basic definitions:

- Fact: a statement that can be supported by objective evidence such as observation, argument, or research.

- Opinion: a statement whose truth depends on someone’s desire(s) rather than objective evidence. Opinions that cannot be supported by objective evidence are at most subjectively true.

Of course, the tricky part is that most people do not label statements as fact and opinion, so you need to be aware and recognize the difference as you go about honing your critical thinking skills.

You probably have heard the old saying “Everyone is entitled to their own opinions,” which may be true, but conversely not everyone is entitled to their own facts. Facts are true for everyone, not just those who want to believe in them. For example, “mice are mammals” is a fact since it has been established by scientific research. In contrast, “mice make the best pets” is an opinion (since best means whatever one likes the best—and that is a matter of one’s subjective desires).

Facts vs. opinion

Determine if the following statements are facts or opinions based on just the information provided here, referring to the basic definitions above. Some people consider scientific findings to be opinions even when they are convincingly backed by reputable evidence and experimentation. However, remember the definition of fact—verifiable by research or observation. Think about what other research you may have to conduct to make an informed decision.

- Oregon is a state in the United States. (How would this be proven?)

- Beef is made from cattle. (See current legislation concerning vegetarian “burgers.”)

- Increased street lighting decreases criminal behavior. (What information would you need to validate this claim?)

- In 1952, Elizabeth became Queen of England. (What documents could validate this statement?)

- Oatmeal tastes plain. (What factors might play into this claim?)

- Acne is an embarrassing skin condition. (Who might verify this claim?)

- Kindergarten decreases student dropout rates. (Think of different interest groups that may take sides on this issue.)

- Carbohydrates promote weight gain. (Can you determine if this is a valid statement?)

- Cell phones cause brain tumors. (What research considers this claim?)

- Immigration is good for the US economy. (What research would help you make an informed decision on this topic?)

Defending against Bias

Once you have all your information gathered and you have checked your sources for currency and validity, you need to direct your attention to how you’re going to present your now well-informed analysis. Be careful on this step to recognize your own possible biases (metacognition). Facts are verifiable statements; opinions are statements without supporting evidence. Stating an opinion is just that. You could say, “Blue is the best color,” and that would be your opinion. In contrast, suppose you were to conduct research and find the use of blue paint in mental hospitals reduces patients’ heart rates by twenty-five percent and contributes to fewer angry outbursts from patients. In that case, the statement “blue paint in mental hospitals reduces patients’ heart rate by twenty-five percent” would be a fact supported by objective evidence.

Not everyone will accept your analysis, which can be frustrating. Most people resist change and have firm beliefs on both important issues and less significant preferences. With all the competing information surfacing online, on the news, and in general conversation, you can understand how confusing it can be to make any decisions. Look at all the reliable, valid sources that claim different approaches to be the best diet for healthy living: ketogenic, low-carb, vegan, vegetarian, low fat, raw foods, paleo, Mediterranean, etc. All you can do in this sort of situation is conduct your own serious research, check your sources, and write clearly and concisely to provide your analysis of the information for consideration. You cannot force others to accept your stance, but you can show your evidence in support of your thinking, being as persuasive as possible without lapsing into your own personal biases.

critical thinking: clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do, often as a result of challenging assumptions

opinions: statements offered without supporting evidence

- College Success. Authored by : Matthew Van Cleave. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : Critical and Creative Thinking Program. Located at : http://cct.wikispaces.umb.edu/Critical+Thinking . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Thinking Critically. Authored by : UBC Learning Commons. Provided by : The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Campus. Located at : https://learningcommons.ubc.ca/student-toolkits/thinking-critically/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- College Success. Authored by : Amy Baldwin; Modified by Lumen Learning. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/7-4-critical-thinking . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Thought-experiment-free-falling-bodies. Provided by : Wikimedia Commons. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thought-experiment-free-falling-bodies.svg . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking.wmv. Authored by : Lawrence Bland. Located at : https://youtu.be/WiSklIGUblo . License : All Rights Reserved

Reflective Learning, Reflective Teaching

- First Online: 10 October 2018

Cite this chapter

- Yasser El Miedany 2 , 3

2170 Accesses

2 Citations

Reflection is an active and aware process that can occur anytime and anywhere. It functions to help us, or our students, to recapture, relive, make sense of, think about, contextualize and evaluate an experience in order to make decisions and choices about what we have experienced, how we have experienced and what we will or will not do next. Engaging in self-reflection should involve a move from this semiconscious, informal approach to a more explicit, intentional formal approach. At the educational level, formal reflection draws on research and theory and provides guidance as well as frameworks for practice, which enables the teacher to learn from and potentially enhance their career (and consequently their awareness of the reflection process) which can be applied to any aspect of teaching. This chapter will discuss the art and science of reflection, characters of reflective learning, reflecting on one’s own practice, reflective teaching and how to become a reflective learner.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Effective pedagogy, The New Zealand Curriculum. 2014. p. 34. http://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/The-New-Zealand-Curriculum#effective_pedagogy . Accessed on 6 Apr 2018.

Boud D, Keogh R, Walker D. Reflection: turning experience into learning. London: Kogan Page; 1985.

Google Scholar

Johns C, Freshwater D. Transforming nursing through reflective practice. London: Blackwell Science; 1998.

Reid B. ‘But we’re doing it already!’ Exploring a response to the concept of reflective practice in order to improve its facilitation. Nurse Educ Today. 1993;13:305–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Jarvis P. Reflective practice and nursing. Nurse Educ Today. 1992;12:174–81.

Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2013.

Johnson M. The forgotten ‘R’: using reflection to speed student learning. 2017. https://matthewmjohnson.com/2017/11/30/why-your-students-should-probably-be-doing-more-reflections/ . Accessed on 8th Apr 2018.

Dewey J. How we think. Boston: D.C. Heath; 1910. p. 6.

Book Google Scholar

Schon D. The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith; 1983.

Schon D. Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

Kolb DA, Fry R. Toward an applied theory of experiential learning. In: Cooper C, editor. Theories of group process. London: Wiley; 1975.

Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1984.

Pedlar M, Burgoyne J, Boydell T. A manager’s guide to self-development. 4th ed. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

Kolb DA, Boyatzis RE. Experiential learning theory: previous research and new directions. In: Sternberg RJ, Zhang LF, editors. Perspectives on cognitive learning and thinking styles. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000.

Gibbs G. Learning in doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. London: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development, Oxford Polytechic; 1988.

Gibbs G. Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning. London: Brookes Oxford University; 1998.

Bulman, Schultz. In: Bulman C, Schutz S, editors. Reflective practice in nursing. 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

Gibbs’ reflective cycle. Academic Services & Retention Team, University of Cumbria; 2016. https://my.cumbria.ac.uk/media/MyCumbria/Documents/ReflectiveCycleGibbs.pdf . Accessed on 8th Apr 2018.

Johns C. Becoming a reflective practitioner. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2000.

Rolfe G, Freshwater D, Jasper M. Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2001.

Maughan C, Webb J. Small group learning and assessment. 2001. Retrieved 11 Apr 2018, from the Higher Education Academy Web site: http://www.ukcle.ac.uk/resources/temp/assessment.html .

Barksby J, et al. A new model of reflection for clinical practice. Nurs Times. 2015;111(34/35):21–3.

PubMed Google Scholar

Forrest MES. Learning and teaching in action. Health Inf Libr J. 2008;25:229–32.

Article Google Scholar

Hatton N, Smith D. Reflection in teacher education-towards definition and implementation. Teach Teach Educ. 1995;11(1):33–49.

Brockbank A, McGill I. Facilitating reflective learning in higher education. 2nd ed. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2007.

Surgenor P. Reflective practice: a practical guide. UCD teaching and learning. 2011. https://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/Reflective%20Practice.pdf .

Boyd E, Fales A. Learning: the key to learning from experience. J Humanist Psychol. 1983;23(2):99–117.

Kember D, Kelly M. Improving teaching through action research, HERDSA Green Guide no. 14. Sydney: HERDSA; 1993.

Baumgartner LM. An update on transformational learning. New Dir Adult Contin Educ. 2001;2001:15–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.4 .

Biggs J, Tang C. Teaching for quality learning. Berkshire: SRHE & Open University Press; 2007.

www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice.asp .

Craft M. Reflective writing and nursing education. J Nurs Educ. 2005;44(2):53–7.

Burrows DE. The nurse teacher’s role in the promotion of reflective practice. Nurse Educ Today. 1995;15(5):346–50.

The NHS Knowledge and Skills Framework (NHS KSF) and the development review process, Department of Health, October 2004. Available from www.nhsemployers.org/agendaforchange .

Healthcare evaluation data system (HED). https://www.hed.nhs.uk/info/hed-system.htm .

The British Society for Rheumatology. Peer Review Guidance. https://www.rheumatology.org.uk/Portals/0/Policy/Peer%20review/Peer%20Review%20Guidance.pdf .

Huxley A. Texts & pretexts: an anthology with commentaries. https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/92753-experience-is-not-what-happens-to-a-man-it-is .

Richert AE. Teaching teachers to reflect: a consideration of program structure. J Curric Stud. 1990;22(6):309–527.

Durfee A. Frameworks for Reflection. Eutopia. 2018. https://www.edutopia.org/article/frameworks-reflection . Accessed on 14th Apr 2018.

Elboj C, Puigdellívol I, Soler M, Valls R. Comunidades d Aprendizaje. Transformar la educación. Barcelona: Graó; 2002.

Edmunds H. A model for reflective practice and peer supervision groups. 2012. http://www.brightontherapycentre.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Edmunds-H-2012-Model-for-Reflective-Practice-and-Peer-Supervision-in-Mental-Health-Services.pdf . Accessed on 14th Apr 2018.

Halpern DF. Thought and knowledge: an Introduction to critical thinking. 5th ed. New York: Psychology Press; 2014.

Loszalka T. Learning and Instruction Section (NY) KaAMS: a PBL environment facilitating reflective thinking. 2001.

Lunenberg M, Korthagen F. Experience, theory and practice wisdom in teaching and teacher education. Teach Teach. 2009;15(2):225–40.

Hobson A. Student teachers perceptions of school-based mentoring in initial teacher training (ITT). Mentoring Tutoring Partnership Learn. 2002;10(1):5–20.

Jones M, Straker K. What informs mentors practice when working with trainees and newly qualified teachers? An investigation into mentors’ professional knowledge base. J Educ Teach. 2006;32(2):165–84.

Finlay L. Reflecting on reflective practice. PBPL CETL, Open University. [Online]. 2008. Available at http://www.open.ac.uk/opencetl/resources/pbpl-resources/finlay-l-2008-reflecting-reflective-practice-pbpl-paper-52 . Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

Ixer G. There’s no such thing as reflection. Br J Soc Work. 1999;29(4):513–27.

LaBoskey VK. Development of reflective practice. A study of preservice teachers. New York: Teachers College Press; 1994.

Cartwright L. How consciously reflective are you? In: McGregor D, Cartwright L, editors. Developing reflective practice: a guide for beginning teachers. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2011.

Mezirow J. Learning to think like an adult: core concepts of transformation theory. In: Mezirow J, et al., editors. Learning as transformation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000. p. 3–34.

McGregor D, Cartwright L. Developing reflective practice: a guide for beginning teachers. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2011.

Bordieu P, Wacquant L. An invitation to reflexive sociology. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1992.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

King’s College London, Darent Valley Hospital, Dartford, Kent, UK

Yasser El Miedany

Rheumatology and Rehabilitation, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

El Miedany, Y. (2019). Reflective Learning, Reflective Teaching. In: Rheumatology Teaching. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98213-7_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98213-7_12

Published : 10 October 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-98212-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-98213-7

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Mission, Vision, Values

- Upcoming Events

- CETL Monthly Newsletter

- Opportunities at CETL

- Custom Programs

- Micro-credentials

- Mutual Mentoring Groups

- Faculty Poster Printing

- Personalized Services

- About SoTL and Offerings

- Hopscotch 4-SoTL

- Call for Proposals

- Information For Participants

- Directory of Conferences

- Directory of Journals

- Graduate Student Professional Development

- Faculty Who Teach Part Time

- SoTL Manuscript Completion Program

- SoTL Conference Presentation Funds

- Student Success Faculty Learning Communities

- Teaching Academy for Part-Time Faculty

- Tenured Faculty Enhancement Leave

- Open-Theme Course Redesign Institute

- Starting Blocks – Student Success Champions

- Celebration of Teaching Day

- Expanding the NEST

- Early Career Faculty Onboarding Series

- New Faculty Orientation

- Faculty Awards Home

- USG Regents' Teaching Excellence Awards

- KSU Faculty Awards

- AI & Teaching

- Governor's Teaching Fellows Program

- USG Teaching and Learning Conference

- National Center for Faculty Development & Diversity

- Teaching Essentials

- Teaching at KSU FAQs

- New/Early Career Faculty Resources

- Contemplative Practices

Levels of Reflective Thought

- SoTL Summit

- USG and KSU Faculty Awards

by Michelle Head, CETL Scholarly Teaching Fellow for Reflective Practices

This article is part of the larger, Reflective Practices for Teaching .

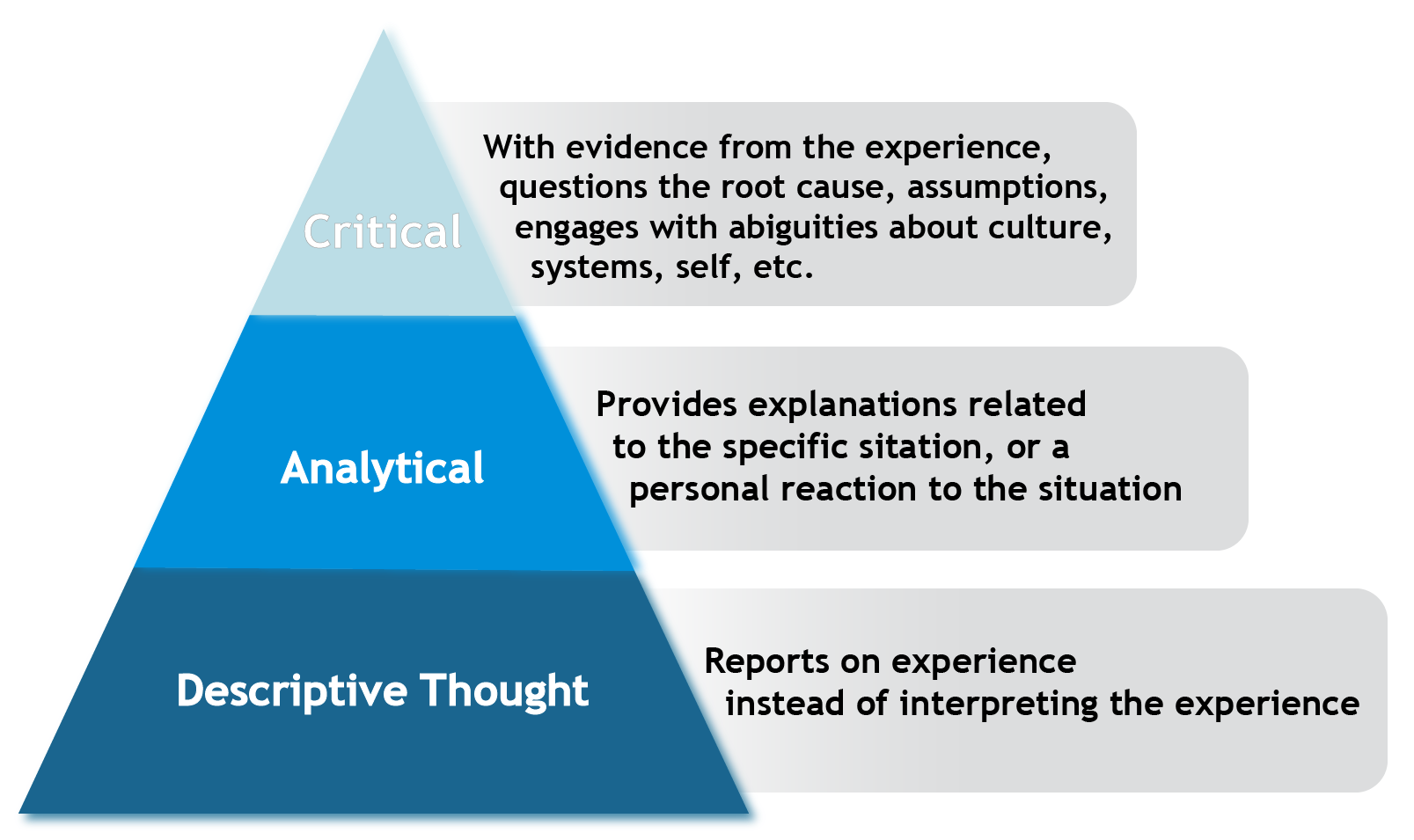

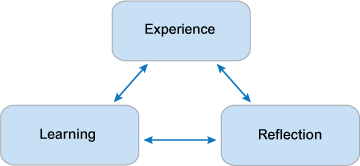

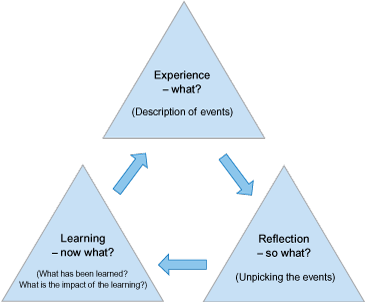

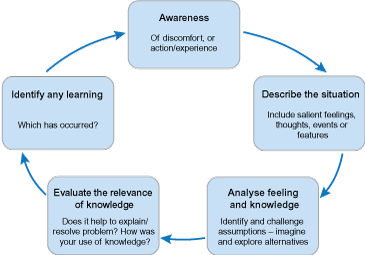

The literature often differentiates between three levels of reflection, as shown in the figure below.

Critical reflection is the highest level of reflection and often the most difficult for students to achieve. As the learner composes a critical reflection, they will often engage in a description of the event, and reason through the experience before extending their understanding of the experience to consider how it aligns or conflicts with the learner already knows.

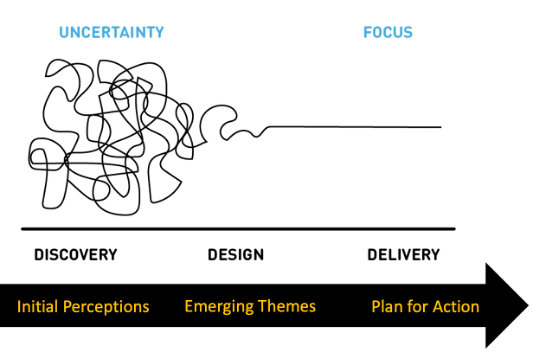

Critical reflection parallels very well the design process. At the start, the learner may be mulling over a number of thoughts related to the experience. They then begin to observe common themes that emerge from their experiences that allow the learner to articulate what they have learned from the experience. As a result, it is helpful to think of ways to scaffold the student's reflection process to move them toward this level of reflection. See the section on Constructing Reflection Prompts to Promote Critical Reflection .

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

Parent Portal

Extracurriculars

Reflective Practice: A Critical Thinking Study Method

In the ever-evolving landscape of education and self-improvement, the quest for effective study techniques is unceasing. One such technique that has gained substantial recognition is reflective practice. Rooted in the realms of experiential learning and critical thinking, reflective practice goes beyond pure memorisation and aims to foster a deeper understanding of concepts.

In this article, we’ll explore the essence of reflective practice as a study technique and how it can be harnessed to elevate the learning experience.

What is Reflective Learning?

The concept of reflective practice has been explored by many researchers , including John Dewey. His work states that reflective learning is more than just a simple review of study material. It's an intentional process that encourages students to examine their experiences, thoughts, and actions. This process aims to uncover insights and connections that lead to enhanced comprehension. The essence of reflective practice lies in its ability to turn information consumption into an active cognitive exercise that leads to the understanding and retention of information.

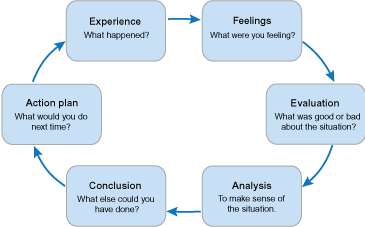

At its core, reflective learning involves several key steps:

- Experience : the first step to reflective learning is to engage with the material, whether it's a lecture, a reading, a discussion, or any other learning experience.

- Reflection : after engaging with the material to be understood it’s important to take time to ponder and evaluate the experience. This involves questioning what was learnt, why it was learnt, and how it fits into the larger context of the subject matter.

- Analysis : once the information has been questioned, it’s important to dive deeper into the experience by analysing the components, concepts, and connections. Explore how the new information relates to what you already know.

- Synthesis : it’s then time to integrate the new knowledge with your existing understanding, creating a cohesive mental framework that bridges the gaps between concepts.

- Application : it’s then important to consider how this newly acquired knowledge can be applied in real-life scenarios or to solve problems, thus enhancing its practical relevance.

- Feedback and adjustment : the final step is to reflect on the effectiveness of the learning process. What worked well? What could be improved? This step encourages continuous refinement of your study techniques.

The Benefits of Reflective Practice

There are a variety of benefits that reflective practice can offer students as they attempt to understand and retain new information, making the studying process much more effective.

Deeper Understanding

Reflective practice prompts students to go beyond surface-level comprehension. By dissecting and analysing the material, students are able to gain a more profound understanding of the subject matter. When engaging in reflective practice, you're not just skimming the surface of the information; you're actively delving into the core concepts, identifying underlying relationships, and unravelling the intricacies of the topic.

Imagine you're reading a challenging chapter in your history textbook.Rather than quickly flipping through the pages, using reflective practice would mean taking a moment to think about why this historical event is important. You might wonder how it connects to events you've learnt about before, and how it might have shaped the world we live in today. By taking the time to really think about these things, you'll start to see patterns and connections that make the topic much more interesting and understandable.

Critical Thinking

This technique nurtures critical thinking skills by encouraging individuals to evaluate and question information, enhancing their ability to think logically and make informed judgements. Critical thinking involves analysing information, assessing its validity and reliability, and discerning its relevance. Reflective practice compels you to question the material, explore its underlying assumptions, and consider different perspectives.

If we once again use history as an example, a reflective practice will prompt you to question the biases of the sources, evaluate the motivations of the individuals involved, and critically assess the long-term impact of the event. These analytical skills extend beyond academia, enriching your ability to evaluate information in everyday situations and make informed decisions.

Long-Tern Retention

Engaging with material on a reflective level enhances memory retention. When you actively connect new information to existing knowledge, it becomes more ingrained in your memory. This process is often referred to as ‘elaborative rehearsal’, where you link new information to what you already know, creating meaningful connections that make the material easier to recall in the future.

For example, when learning a new language, reflecting on how certain words or phrases relate to your native language or personal experiences can help you remember them more effectively.

Personalisation

Reflective practice is adaptable to various learning styles. It allows students to tailor their approach to fit their strengths, preferences, and pace. This is because reflective practice is a self-directed process, allowing you to shape it in ways that align with your individual learning style .

For instance, if you're a visual learner, you might create concept maps or diagrams during your reflective sessions to visually represent the connections between ideas. However, if you're an auditory learner, you might prefer recording your reflections as spoken thoughts.

Real-Life Application

By encouraging students to consider how knowledge can be applied practically, reflective practice bridges the gap between theoretical learning and real-world scenarios. This benefit is especially valuable as you are preparing to tackle challenges beyond the classroom .

For example, if you're studying economics, reflective practice prompts you to think about how the principles you're learning can be applied to analyse current economic issues or make informed personal financial decisions.

Self-Awareness

Reflective practice cultivates self-awareness, as students learn about their thought processes, learning preferences, and areas of growth. As you reflect on your learning experiences, you become attuned to how you absorb information, what strategies work best for you, and where you might encounter challenges.

How to Apply Reflective Learning

Reflective learning can easily be integrated into your study routine, all it takes is a bit of planning, time and patience in order to get used to it.

Set Aside Time

Dedicate specific time slots for reflective practice in your study routine. This could be after a lecture, reading a chapter, or completing an assignment.

Allocating dedicated time for reflective practice ensures that you prioritise this valuable technique in your learning process. After engaging with new material, take a few moments to step back and contemplate what you've learnt. This practice prevents information overload and provides an opportunity for your brain to process and make connections.

For example, if you've just attended a lecture, set aside 10–15 minutes afterwards, or as soon as you can, to reflect on the main points, key takeaways, and any questions that arose during the session.

Create a Reflection Space

Creating a conducive environment for reflection is crucial. Find a quiet and comfortable space where you can concentrate without interruptions. Having a designated journal or digital note-taking app allows you to capture your thoughts systematically.

A voice recorder can be particularly helpful for those who prefer verbalising their reflections.

The act of recording your reflections also adds a layer of accountability, making it easier to track your progress over time.

Ask Thoughtful Questions

Asking insightful questions is at the heart of reflective practice. Challenge yourself to go beyond the superficial understanding of a concept by posing thought-provoking inquiries.

For instance, if you've just read a chapter in a textbook, consider why the concepts covered are significant in the larger context of the subject. Reflect on how these ideas relate to your prior knowledge and experiences. Additionally, explore real-world scenarios where you could apply the newfound knowledge. This will enhance your comprehension and problem-solving skills.

Review Regularly

Revisiting your reflections is akin to reviewing your study notes. Regularly returning to your reflections reinforces your understanding of the material. Over time, you might notice patterns in your thinking, areas where you consistently struggle, or subjects that spark your curiosity.

This insight can guide your future study sessions and help you allocate more time to topics that need a little more attention.

Engage in Dialogue

Sharing your reflections with others opens the door to valuable discussions. Conversations with peers, parents, teachers, or mentors offer different viewpoints and insights you might not have considered on your own. Explaining your thoughts aloud also helps consolidate your understanding, as articulating concepts requires a deeper level of comprehension.

Ultimately, engaging in dialogue enriches your learning experience and enables you to refine your thoughts through constructive feedback.

A Reflective Learner is A Life Long Learner

Reflective learning has the remarkable ability to cultivate a love for learning and foster a lifelong learner mindset.

This method will encourage you to actively engage with your learning experiences, critically examine your knowledge, and apply insights to real-life situations. This process of examination, questioning, and application will nurture intrinsic motivation , curiosity, and ownership of learning.

This will also empower you to view challenges as opportunities for growth and to embrace a mindset of continuous improvement. This joy of discovery, combined with collaborative interactions, can also strengthen your sense of community and amplify the satisfaction you derive from the learning process.

Ultimately, reflective practice instils a belief in the value of lifelong learning, encouraging you to seek out new knowledge, explore diverse fields, and continuously evolve intellectually and personally.

Download Your Free Printable Homeschool Planner

Everything you need to know about setting up your homeschooling schedule with a free printable PDF planner.

Other articles

- More Resources

CONTRASTS BETWEEN CRITICAL AND REFLECTIVE THINKING

- Reed Geertsen + −

How to Cite

Download citation.

Download this resource to see full details. Download this resource to see full details.

When using resources from TRAILS, please include a clear and legible citation.

Similar Resources

- Reed Geertsen, CONTRASTS BETWEEN CRITICAL AND REFLECTIVE THINKING , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Reed Geertsen, Instructions for Critical vs. Reflective Thinking Exercise , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Christina M. Stern, Gendered Minds and the Power to Think:Highlighting the History of Sexism in the Sociology Classroom , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Nadejda Chapkina, Class Discussion, Projects, and Critical Thinking Exercises: More Discussion and Critical Thinking Questions , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Tom Mayer, Critical Thinking in Sociology , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Trina Smith, THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT GENDER DISCUSSION QUESTIONS , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Sara Steen, Sociology 4461 Critical Thinking: Consumerism in America , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- DESMOND M. CONNOR, CONSTRUCTIVE CITIZEN PARTICIPATION: PRACTICING UTOPIAN THINKING , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

- Danielle M Giffort, Teaching Healthcare Students How to Think Sociologically , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: TRAILS Featured Resources

- Zachary Simoni, Critical Thinking and Media Literacy In-Class Assignment , TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology: All TRAILS Resources

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 > >>

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this resource.

All ASA members get a subscription to TRAILS as a benefit of membership. Log in with your ASA account by clicking the button below.

By logging in, you agree to abide by the TRAILS user agreement .

Our website uses cookies to improve your browsing experience, to increase the speed and security for the site, to provide analytics about our site and visitors, and for marketing. By proceeding to the site, you are expressing your consent to the use of cookies. To find out more about how we use cookies, see our Privacy Policy .

- Deakin Library

- Learning and Teaching

Critical reflection for assessments and practice

- Reflective practice

Critical reflection for assessments and practice: Reflective practice

- Critical reflection

- How to reflect

- Critical reflection writing

- Recount and reflect

What is reflective practice?

"In general, reflective practice is understood as the process of learning through and from experience towards gaining new insights of self and/or practice. This often involves examining assumptions of everyday practice."

Linda Finlay - Reflecting on 'Reflective practice' (2008)

Reflection is critical to being a conscious, effective practitioner in any discipline. The important thing to keep in mind is that reflecting by itself is not reflective practice. Practice is tied into active, impactful change that emerges from deep reflective learning .

Thinking and doing

Reflective practice is the act of thinking about your experiences in order to learn from them to shape what you do in the future. It therefore includes all aspects of your practice (e.g. relationships, interactions, learning, assessments, behaviours, and environments). It also includes examining how your practice is influenced by your own world views and gaining insights and other perspectives to inform future decision making.

Why reflect?

Reflective practice benefits you on both professional and personal levels. Using critical reflection as a tool can give you insight and positively impact your study, your wellbeing and your worklife. Click the plus icons (+) to view some benefits of reflective practice.

Text version

Activity overview

This interactive hotspot activity outlines 6 benefits of reflective practice. The hotspots are displayed as plus (+) icons that can be clicked to reveal the benefits, as follows

Benefit 1: Creativity

Reflective practice sparks creativity. By engaging in critical reflection to change practice you are making time and space for innovation. It enables new ways of thinking, feeling and doing.

Benefit 2: Develops your skills and knowledges

Engaging with critical reflection processes as part of reflective practice is a key learning tool. Continual development of skills and knowledges is part of student, work and personal life. Reflective practice helps you identify areas to improve on or strengthen.

Benefit 3: Emotional intelligence

Reflection is at the heart of understanding our emotions and their impact on our behaviours. It also underpins our ability to contextualise the behaviours of others. Reflective practice builds your emotional intelligence which is a critical skill for working with others and for our own wellbeing.

Benefit 4: Self-awareness

Reflective practice fosters new ways of thinking, feeling and behaving. As part of that it helps you step back and reflect on assumptions and biases. Challenging set ways of thinking about people, situations or information can stimulate you to open up your perspective.

Benefit 5: Wellbeing