Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Methods & Data Analysis

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

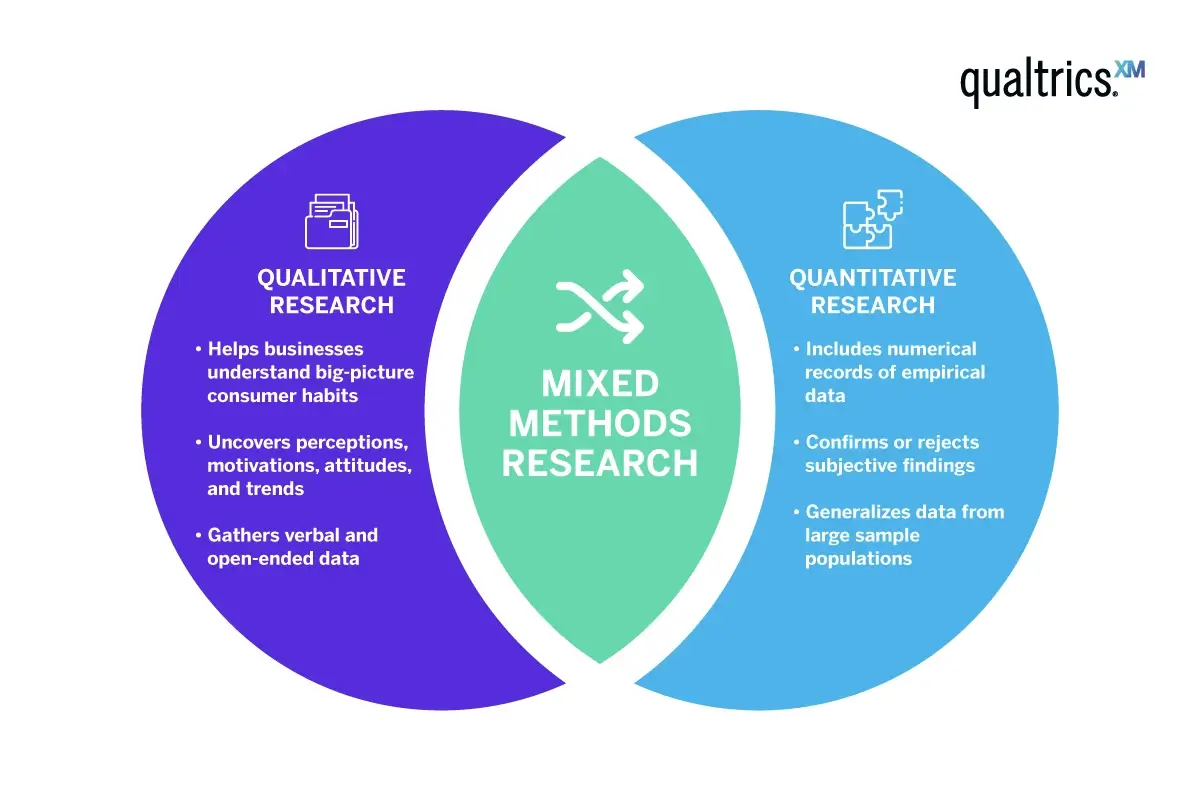

The main difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the type of data they collect and analyze.

Quantitative data is information about quantities, and therefore numbers, and qualitative data is descriptive, and regards phenomenon which can be observed but not measured, such as language.

- Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical methods. The aim is to produce objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed numerically. Quantitative research is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions.

- Qualitative research gathers non-numerical data (words, images, sounds) to explore subjective experiences and attitudes, often via observation and interviews. It aims to produce detailed descriptions and uncover new insights about the studied phenomenon.

On This Page:

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively perceives and gives meaning to their social reality.

Qualitative data is non-numerical data, such as text, video, photographs, or audio recordings. This type of data can be collected using diary accounts or in-depth interviews and analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis.

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 2)

Interest in qualitative data came about as the result of the dissatisfaction of some psychologists (e.g., Carl Rogers) with the scientific study of psychologists such as behaviorists (e.g., Skinner ).

Since psychologists study people, the traditional approach to science is not seen as an appropriate way of carrying out research since it fails to capture the totality of human experience and the essence of being human. Exploring participants’ experiences is known as a phenomenological approach (re: Humanism ).

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with meaning, subjectivity, and lived experience. The goal is to understand the quality and texture of people’s experiences, how they make sense of them, and the implications for their lives.

Qualitative research aims to understand the social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as participants feel or live it. Thus, people and groups are studied in their natural setting.

Some examples of qualitative research questions are provided, such as what an experience feels like, how people talk about something, how they make sense of an experience, and how events unfold for people.

Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context. It can be used to generate hypotheses and theories from the data.

Qualitative Methods

There are different types of qualitative research methods, including diary accounts, in-depth interviews , documents, focus groups , case study research , and ethnography .

The results of qualitative methods provide a deep understanding of how people perceive their social realities and in consequence, how they act within the social world.

The researcher has several methods for collecting empirical materials, ranging from the interview to direct observation, to the analysis of artifacts, documents, and cultural records, to the use of visual materials or personal experience. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 14)

Here are some examples of qualitative data:

Interview transcripts : Verbatim records of what participants said during an interview or focus group. They allow researchers to identify common themes and patterns, and draw conclusions based on the data. Interview transcripts can also be useful in providing direct quotes and examples to support research findings.

Observations : The researcher typically takes detailed notes on what they observe, including any contextual information, nonverbal cues, or other relevant details. The resulting observational data can be analyzed to gain insights into social phenomena, such as human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices.

Unstructured interviews : generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

Diaries or journals : Written accounts of personal experiences or reflections.

Notice that qualitative data could be much more than just words or text. Photographs, videos, sound recordings, and so on, can be considered qualitative data. Visual data can be used to understand behaviors, environments, and social interactions.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative research is endlessly creative and interpretive. The researcher does not just leave the field with mountains of empirical data and then easily write up his or her findings.

Qualitative interpretations are constructed, and various techniques can be used to make sense of the data, such as content analysis, grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), or discourse analysis .

For example, thematic analysis is a qualitative approach that involves identifying implicit or explicit ideas within the data. Themes will often emerge once the data has been coded .

Key Features

- Events can be understood adequately only if they are seen in context. Therefore, a qualitative researcher immerses her/himself in the field, in natural surroundings. The contexts of inquiry are not contrived; they are natural. Nothing is predefined or taken for granted.

- Qualitative researchers want those who are studied to speak for themselves, to provide their perspectives in words and other actions. Therefore, qualitative research is an interactive process in which the persons studied teach the researcher about their lives.

- The qualitative researcher is an integral part of the data; without the active participation of the researcher, no data exists.

- The study’s design evolves during the research and can be adjusted or changed as it progresses. For the qualitative researcher, there is no single reality. It is subjective and exists only in reference to the observer.

- The theory is data-driven and emerges as part of the research process, evolving from the data as they are collected.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Because of the time and costs involved, qualitative designs do not generally draw samples from large-scale data sets.

- The problem of adequate validity or reliability is a major criticism. Because of the subjective nature of qualitative data and its origin in single contexts, it is difficult to apply conventional standards of reliability and validity. For example, because of the central role played by the researcher in the generation of data, it is not possible to replicate qualitative studies.

- Also, contexts, situations, events, conditions, and interactions cannot be replicated to any extent, nor can generalizations be made to a wider context than the one studied with confidence.

- The time required for data collection, analysis, and interpretation is lengthy. Analysis of qualitative data is difficult, and expert knowledge of an area is necessary to interpret qualitative data. Great care must be taken when doing so, for example, looking for mental illness symptoms.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Because of close researcher involvement, the researcher gains an insider’s view of the field. This allows the researcher to find issues that are often missed (such as subtleties and complexities) by the scientific, more positivistic inquiries.

- Qualitative descriptions can be important in suggesting possible relationships, causes, effects, and dynamic processes.

- Qualitative analysis allows for ambiguities/contradictions in the data, which reflect social reality (Denscombe, 2010).

- Qualitative research uses a descriptive, narrative style; this research might be of particular benefit to the practitioner as she or he could turn to qualitative reports to examine forms of knowledge that might otherwise be unavailable, thereby gaining new insight.

What Is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research involves the process of objectively collecting and analyzing numerical data to describe, predict, or control variables of interest.

The goals of quantitative research are to test causal relationships between variables , make predictions, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative researchers aim to establish general laws of behavior and phenomenon across different settings/contexts. Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Quantitative Methods

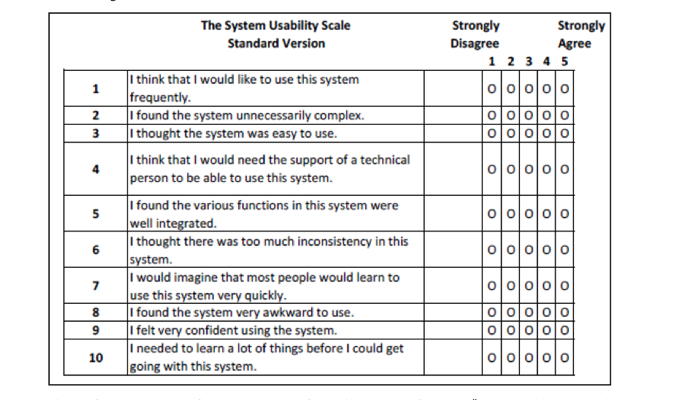

Experiments typically yield quantitative data, as they are concerned with measuring things. However, other research methods, such as controlled observations and questionnaires , can produce both quantitative information.

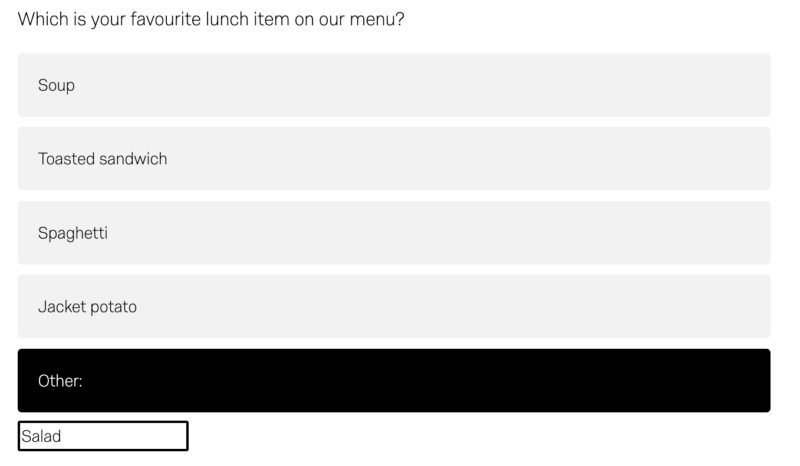

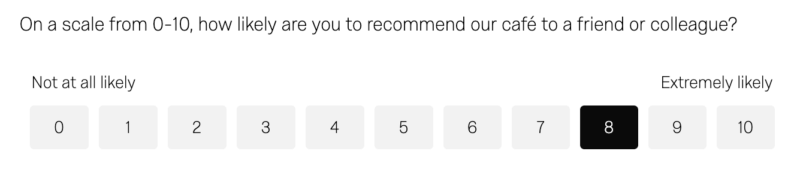

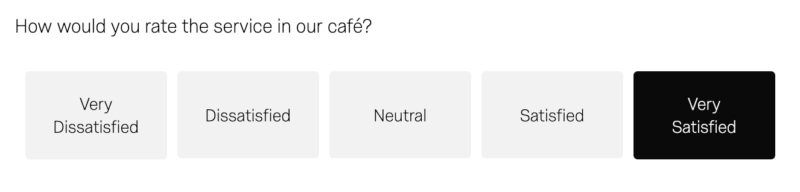

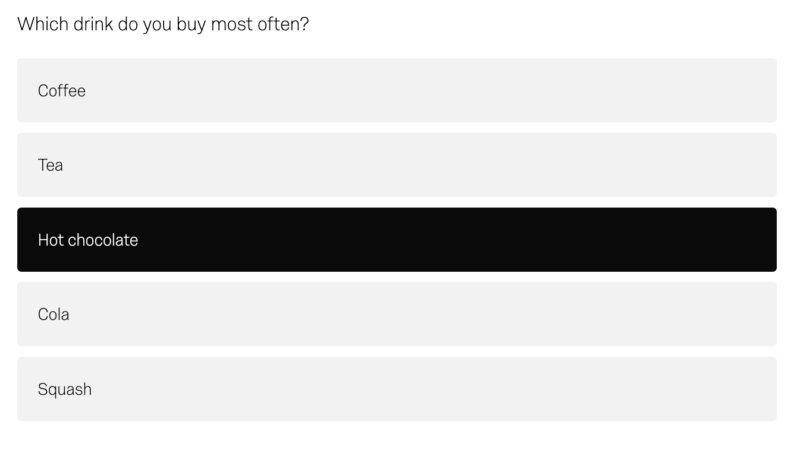

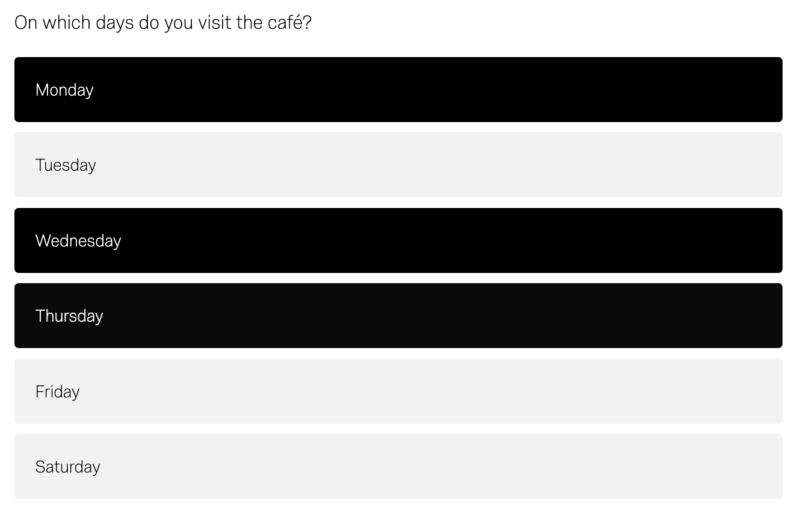

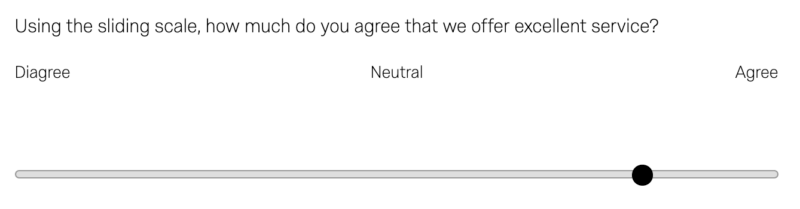

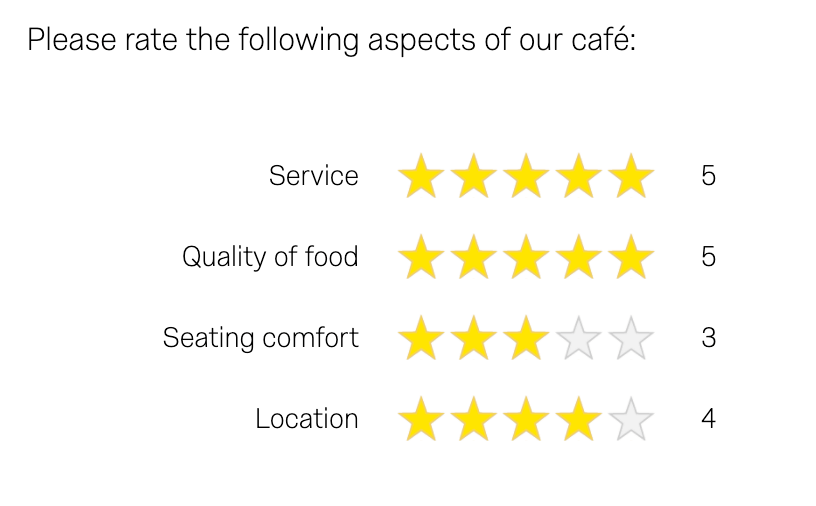

For example, a rating scale or closed questions on a questionnaire would generate quantitative data as these produce either numerical data or data that can be put into categories (e.g., “yes,” “no” answers).

Experimental methods limit how research participants react to and express appropriate social behavior.

Findings are, therefore, likely to be context-bound and simply a reflection of the assumptions that the researcher brings to the investigation.

There are numerous examples of quantitative data in psychological research, including mental health. Here are a few examples:

Another example is the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR), a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess adult attachment styles .

The ECR provides quantitative data that can be used to assess attachment styles and predict relationship outcomes.

Neuroimaging data : Neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI and fMRI, provide quantitative data on brain structure and function.

This data can be analyzed to identify brain regions involved in specific mental processes or disorders.

For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a clinician-administered questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in individuals.

The BDI consists of 21 questions, each scored on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Quantitative Data Analysis

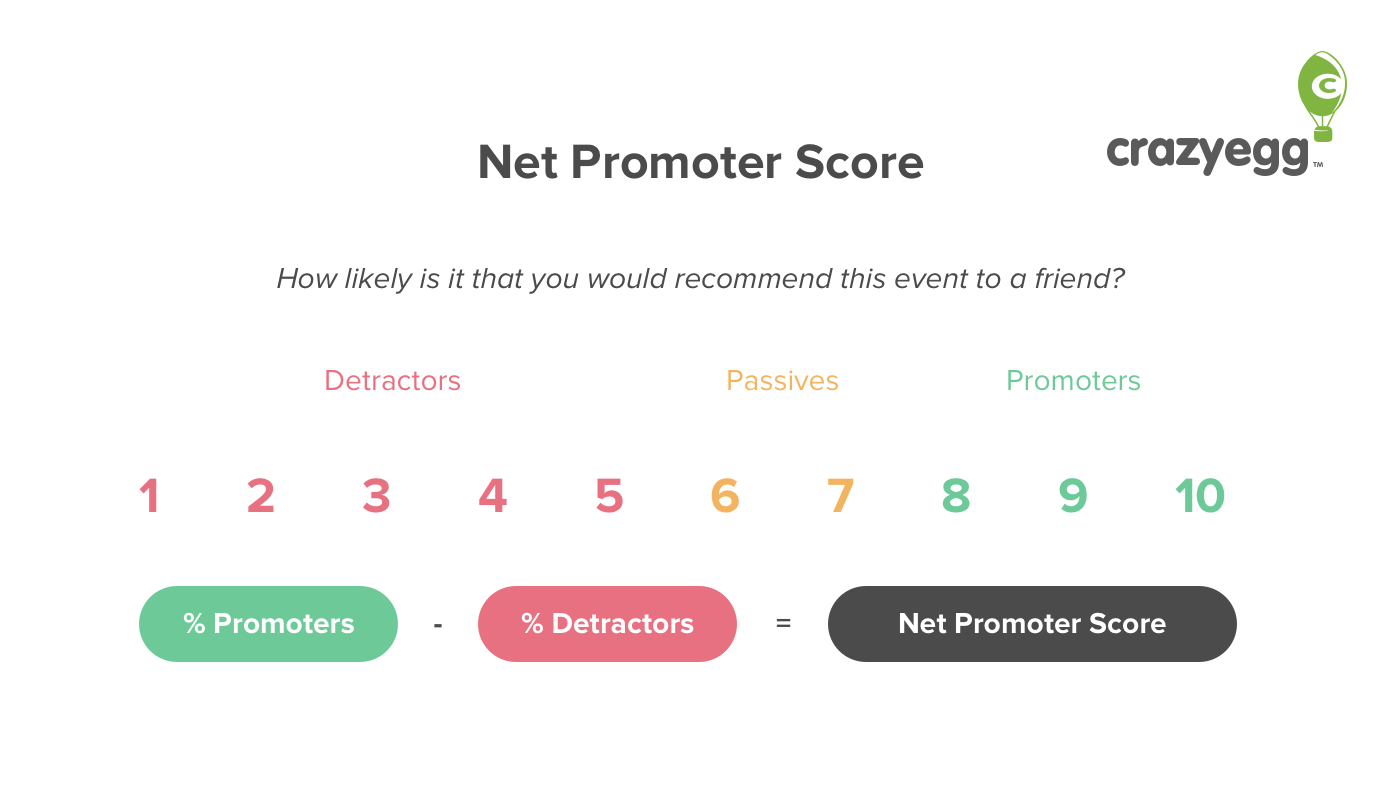

Statistics help us turn quantitative data into useful information to help with decision-making. We can use statistics to summarize our data, describing patterns, relationships, and connections. Statistics can be descriptive or inferential.

Descriptive statistics help us to summarize our data. In contrast, inferential statistics are used to identify statistically significant differences between groups of data (such as intervention and control groups in a randomized control study).

- Quantitative researchers try to control extraneous variables by conducting their studies in the lab.

- The research aims for objectivity (i.e., without bias) and is separated from the data.

- The design of the study is determined before it begins.

- For the quantitative researcher, the reality is objective, exists separately from the researcher, and can be seen by anyone.

- Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Limitations of Quantitative Research

- Context: Quantitative experiments do not take place in natural settings. In addition, they do not allow participants to explain their choices or the meaning of the questions they may have for those participants (Carr, 1994).

- Researcher expertise: Poor knowledge of the application of statistical analysis may negatively affect analysis and subsequent interpretation (Black, 1999).

- Variability of data quantity: Large sample sizes are needed for more accurate analysis. Small-scale quantitative studies may be less reliable because of the low quantity of data (Denscombe, 2010). This also affects the ability to generalize study findings to wider populations.

- Confirmation bias: The researcher might miss observing phenomena because of focus on theory or hypothesis testing rather than on the theory of hypothesis generation.

Advantages of Quantitative Research

- Scientific objectivity: Quantitative data can be interpreted with statistical analysis, and since statistics are based on the principles of mathematics, the quantitative approach is viewed as scientifically objective and rational (Carr, 1994; Denscombe, 2010).

- Useful for testing and validating already constructed theories.

- Rapid analysis: Sophisticated software removes much of the need for prolonged data analysis, especially with large volumes of data involved (Antonius, 2003).

- Replication: Quantitative data is based on measured values and can be checked by others because numerical data is less open to ambiguities of interpretation.

- Hypotheses can also be tested because of statistical analysis (Antonius, 2003).

Antonius, R. (2003). Interpreting quantitative data with SPSS . Sage.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics . Sage.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3, 77–101.

Carr, L. T. (1994). The strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research : what method for nursing? Journal of advanced nursing, 20(4) , 716-721.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide: for small-scale social research. McGraw Hill.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln. Y. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc.

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing research, 17(4) , 364.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. London: Sage

Further Information

- Mixed methods research

- Designing qualitative research

- Methods of data collection and analysis

- Introduction to quantitative and qualitative research

- Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?

- Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data

- Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach

- Using the framework method for the analysis of

- Qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Content Analysis

- Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research: Differences, Examples, and Methods

There are two broad kinds of research approaches: qualitative and quantitative research that are used to study and analyze phenomena in various fields such as natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. Whether you have realized it or not, your research must have followed either or both research types. In this article we will discuss what qualitative vs quantitative research is, their applications, pros and cons, and when to use qualitative vs quantitative research . Before we get into the details, it is important to understand the differences between the qualitative and quantitative research.

Table of Contents

Qualitative v s Quantitative Research

Quantitative research deals with quantity, hence, this research type is concerned with numbers and statistics to prove or disapprove theories or hypothesis. In contrast, qualitative research is all about quality – characteristics, unquantifiable features, and meanings to seek deeper understanding of behavior and phenomenon. These two methodologies serve complementary roles in the research process, each offering unique insights and methods suited to different research questions and objectives.

Qualitative and quantitative research approaches have their own unique characteristics, drawbacks, advantages, and uses. Where quantitative research is mostly employed to validate theories or assumptions with the goal of generalizing facts to the larger population, qualitative research is used to study concepts, thoughts, or experiences for the purpose of gaining the underlying reasons, motivations, and meanings behind human behavior .

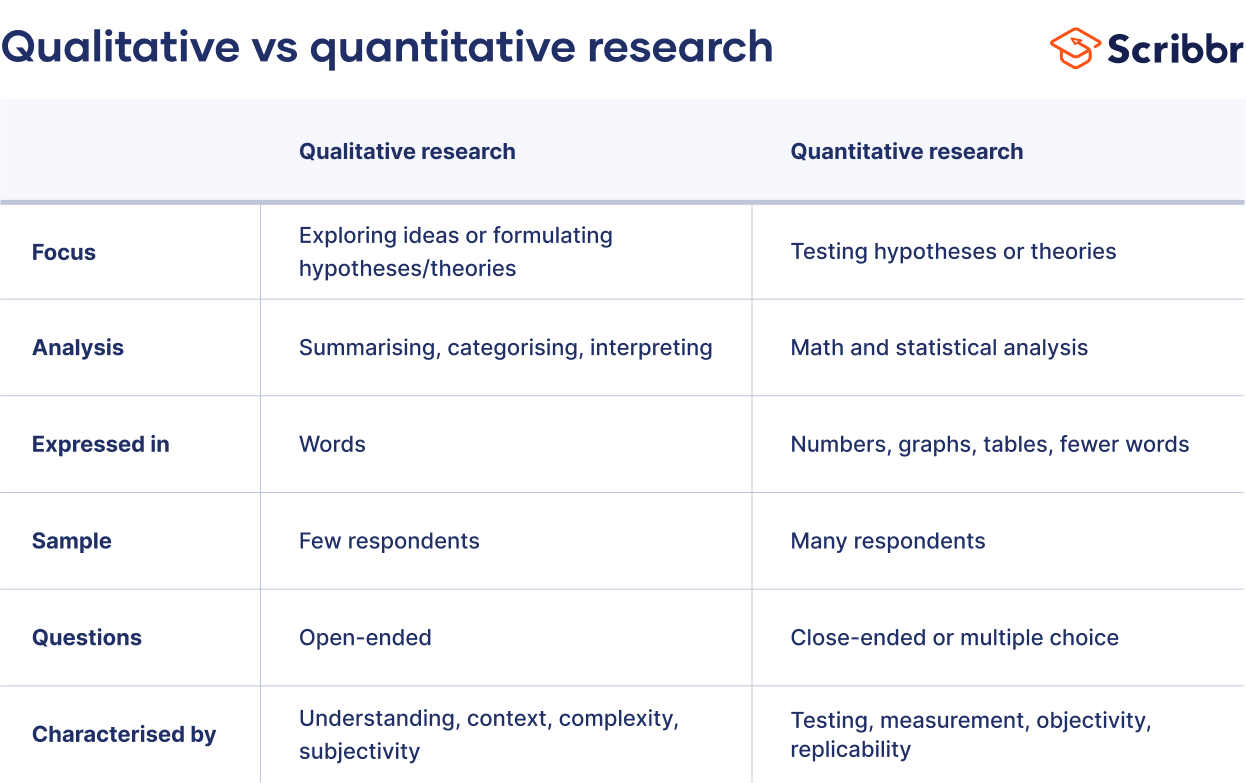

What Are the Differences Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

Qualitative and quantitative research differs in terms of the methods they employ to conduct, collect, and analyze data. For example, qualitative research usually relies on interviews, observations, and textual analysis to explore subjective experiences and diverse perspectives. While quantitative data collection methods include surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis to gather and analyze numerical data. The differences between the two research approaches across various aspects are listed in the table below.

| Understanding meanings, exploring ideas, behaviors, and contexts, and formulating theories | Generating and analyzing numerical data, quantifying variables by using logical, statistical, and mathematical techniques to test or prove hypothesis | |

| Limited sample size, typically not representative | Large sample size to draw conclusions about the population | |

| Expressed using words. Non-numeric, textual, and visual narrative | Expressed using numerical data in the form of graphs or values. Statistical, measurable, and numerical | |

| Interviews, focus groups, observations, ethnography, literature review, and surveys | Surveys, experiments, and structured observations | |

| Inductive, thematic, and narrative in nature | Deductive, statistical, and numerical in nature | |

| Subjective | Objective | |

| Open-ended questions | Close-ended (Yes or No) or multiple-choice questions | |

| Descriptive and contextual | Quantifiable and generalizable | |

| Limited, only context-dependent findings | High, results applicable to a larger population | |

| Exploratory research method | Conclusive research method | |

| To delve deeper into the topic to understand the underlying theme, patterns, and concepts | To analyze the cause-and-effect relation between the variables to understand a complex phenomenon | |

| Case studies, ethnography, and content analysis | Surveys, experiments, and correlation studies |

Data Collection Methods

There are differences between qualitative and quantitative research when it comes to data collection as they deal with different types of data. Qualitative research is concerned with personal or descriptive accounts to understand human behavior within society. Quantitative research deals with numerical or measurable data to delineate relations among variables. Hence, the qualitative data collection methods differ significantly from quantitative data collection methods due to the nature of data being collected and the research objectives. Below is the list of data collection methods for each research approach:

Qualitative Research Data Collection

- Interviews

- Focus g roups

- Content a nalysis

- Literature review

- Observation

- Ethnography

Qualitative research data collection can involve one-on-one group interviews to capture in-depth perspectives of participants using open-ended questions. These interviews could be structured, semi-structured or unstructured depending upon the nature of the study. Focus groups can be used to explore specific topics and generate rich data through discussions among participants. Another qualitative data collection method is content analysis, which involves systematically analyzing text documents, audio, and video files or visual content to uncover patterns, themes, and meanings. This can be done through coding and categorization of raw data to draw meaningful insights. Data can be collected through observation studies where the goal is to simply observe and document behaviors, interaction, and phenomena in natural settings without interference. Lastly, ethnography allows one to immerse themselves in the culture or environment under study for a prolonged period to gain a deep understanding of the social phenomena.

Quantitative Research Data Collection

- Surveys/ q uestionnaires

- Experiments

- Secondary data analysis

- Structured o bservations

- Case studies

- Tests and a ssessments

Quantitative research data collection approaches comprise of fundamental methods for generating numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical or mathematical tools. The most common quantitative data collection approach is the usage of structured surveys with close-ended questions to collect quantifiable data from a large sample of participants. These can be conducted online, over the phone, or in person.

Performing experiments is another important data collection approach, in which variables are manipulated under controlled conditions to observe their effects on dependent variables. This often involves random assignment of participants to different conditions or groups. Such experimental settings are employed to gauge cause-and-effect relationships and understand a complex phenomenon. At times, instead of acquiring original data, researchers may deal with secondary data, which is the dataset curated by others, such as government agencies, research organizations, or academic institute. With structured observations, subjects in a natural environment can be studied by controlling the variables which aids in understanding the relationship among various variables. The secondary data is then analyzed to identify patterns and relationships among variables. Observational studies provide a means to systematically observe and record behaviors or phenomena as they occur in controlled environments. Case studies form an interesting study methodology in which a researcher studies a single entity or a small number of entities (individuals or organizations) in detail to understand complex phenomena within a specific context.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Outcomes

Qualitative research and quantitative research lead to varied research outcomes, each with its own strengths and limitations. For example, qualitative research outcomes provide deep descriptive accounts of human experiences, motivations, and perspectives that allow us to identify themes or narratives and context in which behavior, attitudes, or phenomena occurs. Quantitative research outcomes on the other hand produce numerical data that is analyzed statistically to establish patterns and relationships objectively, to form generalizations about the larger population and make predictions. This numerical data can be presented in the form of graphs, tables, or charts. Both approaches offer valuable perspectives on complex phenomena, with qualitative research focusing on depth and interpretation, while quantitative research emphasizes numerical analysis and objectivity.

When to Use Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Approach

The decision to choose between qualitative and quantitative research depends on various factors, such as the research question, objectives, whether you are taking an inductive or deductive approach, available resources, practical considerations such as time and money, and the nature of the phenomenon under investigation. To simplify, quantitative research can be used if the aim of the research is to prove or test a hypothesis, while qualitative research should be used if the research question is more exploratory and an in-depth understanding of the concepts, behavior, or experiences is needed.

Qualitative research approach

Qualitative research approach is used under following scenarios:

- To study complex phenomena: When the research requires understanding the depth, complexity, and context of a phenomenon.

- Collecting participant perspectives: When the goal is to understand the why behind a certain behavior, and a need to capture subjective experiences and perceptions of participants.

- Generating hypotheses or theories: When generating hypotheses, theories, or conceptual frameworks based on exploratory research.

Example: If you have a research question “What obstacles do expatriate students encounter when acquiring a new language in their host country?”

This research question can be addressed using the qualitative research approach by conducting in-depth interviews with 15-25 expatriate university students. Ask open-ended questions such as “What are the major challenges you face while attempting to learn the new language?”, “Do you find it difficult to learn the language as an adult?”, and “Do you feel practicing with a native friend or colleague helps the learning process”?

Based on the findings of these answers, a follow-up questionnaire can be planned to clarify things. Next step will be to transcribe all interviews using transcription software and identify themes and patterns.

Quantitative research approach

Quantitative research approach is used under following scenarios:

- Testing hypotheses or proving theories: When aiming to test hypotheses, establish relationships, or examine cause-and-effect relationships.

- Generalizability: When needing findings that can be generalized to broader populations using large, representative samples.

- Statistical analysis: When requiring rigorous statistical analysis to quantify relationships, patterns, or trends in data.

Example : Considering the above example, you can conduct a survey of 200-300 expatriate university students and ask them specific questions such as: “On a scale of 1-10 how difficult is it to learn a new language?”

Next, statistical analysis can be performed on the responses to draw conclusions like, on an average expatriate students rated the difficulty of learning a language 6.5 on the scale of 10.

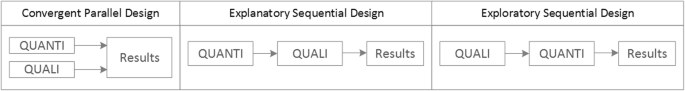

Mixed methods approach

In many cases, researchers may opt for a mixed methods approach , combining qualitative and quantitative methods to leverage the strengths of both approaches. Researchers may use qualitative data to explore phenomena in-depth and generate hypotheses, while quantitative data can be used to test these hypotheses and generalize findings to broader populations.

Example: Both qualitative and quantitative research methods can be used in combination to address the above research question. Through open-ended questions you can gain insights about different perspectives and experiences while quantitative research allows you to test that knowledge and prove/disprove your hypothesis.

How to Analyze Qualitative and Quantitative Data

When it comes to analyzing qualitative and quantitative data, the focus is on identifying patterns in the data to highlight the relationship between elements. The best research method for any given study should be chosen based on the study aim. A few methods to analyze qualitative and quantitative data are listed below.

Analyzing qualitative data

Qualitative data analysis is challenging as it is not expressed in numbers and consists majorly of texts, images, or videos. Hence, care must be taken while using any analytical approach. Some common approaches to analyze qualitative data include:

- Organization: The first step is data (transcripts or notes) organization into different categories with similar concepts, themes, and patterns to find inter-relationships.

- Coding: Data can be arranged in categories based on themes/concepts using coding.

- Theme development: Utilize higher-level organization to group related codes into broader themes.

- Interpretation: Explore the meaning behind different emerging themes to understand connections. Use different perspectives like culture, environment, and status to evaluate emerging themes.

- Reporting: Present findings with quotes or excerpts to illustrate key themes.

Analyzing quantitative data

Quantitative data analysis is more direct compared to qualitative data as it primarily deals with numbers. Data can be evaluated using simple math or advanced statistics (descriptive or inferential). Some common approaches to analyze quantitative data include:

- Processing raw data: Check missing values, outliers, or inconsistencies in raw data.

- Descriptive statistics: Summarize data with means, standard deviations, or standard error using programs such as Excel, SPSS, or R language.

- Exploratory data analysis: Usage of visuals to deduce patterns and trends.

- Hypothesis testing: Apply statistical tests to find significance and test hypothesis (Student’s t-test or ANOVA).

- Interpretation: Analyze results considering significance and practical implications.

- Validation: Data validation through replication or literature review.

- Reporting: Present findings by means of tables, figures, or graphs.

Benefits and limitations of qualitative vs quantitative research

There are significant differences between qualitative and quantitative research; we have listed the benefits and limitations of both methods below:

Benefits of qualitative research

- Rich insights: As qualitative research often produces information-rich data, it aids in gaining in-depth insights into complex phenomena, allowing researchers to explore nuances and meanings of the topic of study.

- Flexibility: One of the most important benefits of qualitative research is flexibility in acquiring and analyzing data that allows researchers to adapt to the context and explore more unconventional aspects.

- Contextual understanding: With descriptive and comprehensive data, understanding the context in which behaviors or phenomena occur becomes accessible.

- Capturing different perspectives: Qualitative research allows for capturing different participant perspectives with open-ended question formats that further enrich data.

- Hypothesis/theory generation: Qualitative research is often the first step in generating theory/hypothesis, which leads to future investigation thereby contributing to the field of research.

Limitations of qualitative research

- Subjectivity: It is difficult to have objective interpretation with qualitative research, as research findings might be influenced by the expertise of researchers. The risk of researcher bias or interpretations affects the reliability and validity of the results.

- Limited generalizability: Due to the presence of small, non-representative samples, the qualitative data cannot be used to make generalizations to a broader population.

- Cost and time intensive: Qualitative data collection can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, therefore, it requires strategic planning and commitment.

- Complex analysis: Analyzing qualitative data needs specialized skills and techniques, hence, it’s challenging for researchers without sufficient training or experience.

- Potential misinterpretation: There is a risk of sampling bias and misinterpretation in data collection and analysis if researchers lack cultural or contextual understanding.

Benefits of quantitative research

- Objectivity: A key benefit of quantitative research approach, this objectivity reduces researcher bias and subjectivity, enhancing the reliability and validity of findings.

- Generalizability: For quantitative research, the sample size must be large and representative enough to allow for generalization to broader populations.

- Statistical analysis: Quantitative research enables rigorous statistical analysis (increasing power of the analysis), aiding hypothesis testing and finding patterns or relationship among variables.

- Efficiency: Quantitative data collection and analysis is usually more efficient compared to the qualitative methods, especially when dealing with large datasets.

- Clarity and Precision: The findings are usually clear and precise, making it easier to present them as graphs, tables, and figures to convey them to a larger audience.

Limitations of quantitative research

- Lacks depth and details: Due to its objective nature, quantitative research might lack the depth and richness of qualitative approaches, potentially overlooking important contextual factors or nuances.

- Limited exploration: By not considering the subjective experiences of participants in depth , there’s a limited chance to study complex phenomenon in detail.

- Potential oversimplification: Quantitative research may oversimplify complex phenomena by boiling them down to numbers, which might ignore key nuances.

- Inflexibility: Quantitative research deals with predecided varibales and measures , which limits the ability of researchers to explore unexpected findings or adjust the research design as new findings become available .

- Ethical consideration: Quantitative research may raise ethical concerns especially regarding privacy, informed consent, and the potential for harm, when dealing with sensitive topics or vulnerable populations.

Frequently asked questions

- What is the difference between qualitative and quantitative research?

Quantitative methods use numerical data and statistical analysis for objective measurement and hypothesis testing, emphasizing generalizability. Qualitative methods gather non-numerical data to explore subjective experiences and contexts, providing rich, nuanced insights.

- What are the types of qualitative research?

Qualitative research methods include interviews, observations, focus groups, and case studies. They provide rich insights into participants’ perspectives and behaviors within their contexts, enabling exploration of complex phenomena.

- What are the types of quantitative research?

Quantitative research methods include surveys, experiments, observations, correlational studies, and longitudinal research. They gather numerical data for statistical analysis, aiming for objectivity and generalizability.

- Can you give me examples for qualitative and quantitative research?

Qualitative Research Example:

Research Question: What are the experiences of parents with autistic children in accessing support services?

Method: Conducting in-depth interviews with parents to explore their perspectives, challenges, and needs.

Quantitative Research Example:

Research Question: What is the correlation between sleep duration and academic performance in college students?

Method: Distributing surveys to a large sample of college students to collect data on their sleep habits and academic performance, then analyzing the data statistically to determine any correlations.

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

Back to School – Lock-in All Access Pack for a Year at the Best Price

Journal Turnaround Time: Researcher.Life and Scholarly Intelligence Join Hands to Empower Researchers with Publication Time Insights

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research in Psychology

- Key Differences

Quantitative Research Methods

Qualitative research methods.

- How They Relate

In psychology and other social sciences, researchers are faced with an unresolved question: Can we measure concepts like love or racism the same way we can measure temperature or the weight of a star? Social phenomena—things that happen because of and through human behavior—are especially difficult to grasp with typical scientific models.

At a Glance

Psychologists rely on quantitative and quantitative research to better understand human thought and behavior.

- Qualitative research involves collecting and evaluating non-numerical data in order to understand concepts or subjective opinions.

- Quantitative research involves collecting and evaluating numerical data.

This article discusses what qualitative and quantitative research are, how they are different, and how they are used in psychology research.

Qualitative Research vs. Quantitative Research

In order to understand qualitative and quantitative psychology research, it can be helpful to look at the methods that are used and when each type is most appropriate.

Psychologists rely on a few methods to measure behavior, attitudes, and feelings. These include:

- Self-reports , like surveys or questionnaires

- Observation (often used in experiments or fieldwork)

- Implicit attitude tests that measure timing in responding to prompts

Most of these are quantitative methods. The result is a number that can be used to assess differences between groups.

However, most of these methods are static, inflexible (you can't change a question because a participant doesn't understand it), and provide a "what" answer rather than a "why" answer.

Sometimes, researchers are more interested in the "why" and the "how." That's where qualitative methods come in.

Qualitative research is about speaking to people directly and hearing their words. It is grounded in the philosophy that the social world is ultimately unmeasurable, that no measure is truly ever "objective," and that how humans make meaning is just as important as how much they score on a standardized test.

Used to develop theories

Takes a broad, complex approach

Answers "why" and "how" questions

Explores patterns and themes

Used to test theories

Takes a narrow, specific approach

Answers "what" questions

Explores statistical relationships

Quantitative methods have existed ever since people have been able to count things. But it is only with the positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte (which maintains that factual knowledge obtained by observation is trustworthy) that it became a "scientific method."

The scientific method follows this general process. A researcher must:

- Generate a theory or hypothesis (i.e., predict what might happen in an experiment) and determine the variables needed to answer their question

- Develop instruments to measure the phenomenon (such as a survey, a thermometer, etc.)

- Develop experiments to manipulate the variables

- Collect empirical (measured) data

- Analyze data

Quantitative methods are about measuring phenomena, not explaining them.

Quantitative research compares two groups of people. There are all sorts of variables you could measure, and many kinds of experiments to run using quantitative methods.

These comparisons are generally explained using graphs, pie charts, and other visual representations that give the researcher a sense of how the various data points relate to one another.

Basic Assumptions

Quantitative methods assume:

- That the world is measurable

- That humans can observe objectively

- That we can know things for certain about the world from observation

In some fields, these assumptions hold true. Whether you measure the size of the sun 2000 years ago or now, it will always be the same. But when it comes to human behavior, it is not so simple.

As decades of cultural and social research have shown, people behave differently (and even think differently) based on historical context, cultural context, social context, and even identity-based contexts like gender , social class, or sexual orientation .

Therefore, quantitative methods applied to human behavior (as used in psychology and some areas of sociology) should always be rooted in their particular context. In other words: there are no, or very few, human universals.

Statistical information is the primary form of quantitative data used in human and social quantitative research. Statistics provide lots of information about tendencies across large groups of people, but they can never describe every case or every experience. In other words, there are always outliers.

Correlation and Causation

A basic principle of statistics is that correlation is not causation. Researchers can only claim a cause-and-effect relationship under certain conditions:

- The study was a true experiment.

- The independent variable can be manipulated (for example, researchers cannot manipulate gender, but they can change the primer a study subject sees, such as a picture of nature or of a building).

- The dependent variable can be measured through a ratio or a scale.

So when you read a report that "gender was linked to" something (like a behavior or an attitude), remember that gender is NOT a cause of the behavior or attitude. There is an apparent relationship, but the true cause of the difference is hidden.

Pitfalls of Quantitative Research

Quantitative methods are one way to approach the measurement and understanding of human and social phenomena. But what's missing from this picture?

As noted above, statistics do not tell us about personal, individual experiences and meanings. While surveys can give a general idea, respondents have to choose between only a few responses. This can make it difficult to understand the subtleties of different experiences.

Quantitative methods can be helpful when making objective comparisons between groups or when looking for relationships between variables. They can be analyzed statistically, which can be helpful when looking for patterns and relationships.

Qualitative data are not made out of numbers but rather of descriptions, metaphors, symbols, quotes, analysis, concepts, and characteristics. This approach uses interviews, written texts, art, photos, and other materials to make sense of human experiences and to understand what these experiences mean to people.

While quantitative methods ask "what" and "how much," qualitative methods ask "why" and "how."

Qualitative methods are about describing and analyzing phenomena from a human perspective. There are many different philosophical views on qualitative methods, but in general, they agree that some questions are too complex or impossible to answer with standardized instruments.

These methods also accept that it is impossible to be completely objective in observing phenomena. Researchers have their own thoughts, attitudes, experiences, and beliefs, and these always color how people interpret results.

Qualitative Approaches

There are many different approaches to qualitative research, with their own philosophical bases. Different approaches are best for different kinds of projects. For example:

- Case studies and narrative studies are best for single individuals. These involve studying every aspect of a person's life in great depth.

- Phenomenology aims to explain experiences. This type of work aims to describe and explore different events as they are consciously and subjectively experienced.

- Grounded theory develops models and describes processes. This approach allows researchers to construct a theory based on data that is collected, analyzed, and compared to reach new discoveries.

- Ethnography describes cultural groups. In this approach, researchers immerse themselves in a community or group in order to observe behavior.

Qualitative researchers must be aware of several different methods and know each thoroughly enough to produce valuable research.

Some researchers specialize in a single method, but others specialize in a topic or content area and use many different methods to explore the topic, providing different information and a variety of points of view.

There is not a single model or method that can be used for every qualitative project. Depending on the research question, the people participating, and the kind of information they want to produce, researchers will choose the appropriate approach.

Interpretation

Qualitative research does not look into causal relationships between variables, but rather into themes, values, interpretations, and meanings. As a rule, then, qualitative research is not generalizable (cannot be applied to people outside the research participants).

The insights gained from qualitative research can extend to other groups with proper attention to specific historical and social contexts.

Relationship Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

It might sound like quantitative and qualitative research do not play well together. They have different philosophies, different data, and different outputs. However, this could not be further from the truth.

These two general methods complement each other. By using both, researchers can gain a fuller, more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

For example, a psychologist wanting to develop a new survey instrument about sexuality might and ask a few dozen people questions about their sexual experiences (this is qualitative research). This gives the researcher some information to begin developing questions for their survey (which is a quantitative method).

After the survey, the same or other researchers might want to dig deeper into issues brought up by its data. Follow-up questions like "how does it feel when...?" or "what does this mean to you?" or "how did you experience this?" can only be answered by qualitative research.

By using both quantitative and qualitative data, researchers have a more holistic, well-rounded understanding of a particular topic or phenomenon.

Qualitative and quantitative methods both play an important role in psychology. Where quantitative methods can help answer questions about what is happening in a group and to what degree, qualitative methods can dig deeper into the reasons behind why it is happening. By using both strategies, psychology researchers can learn more about human thought and behavior.

Gough B, Madill A. Subjectivity in psychological science: From problem to prospect . Psychol Methods . 2012;17(3):374-384. doi:10.1037/a0029313

Pearce T. “Science organized”: Positivism and the metaphysical club, 1865–1875 . J Hist Ideas . 2015;76(3):441-465.

Adams G. Context in person, person in context: A cultural psychology approach to social-personality psychology . In: Deaux K, Snyder M, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology . Oxford University Press; 2012:182-208.

Brady HE. Causation and explanation in social science . In: Goodin RE, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Political Science. Oxford University Press; 2011. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0049

Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers . SAGE Open Med . 2019;7:2050312118822927. doi:10.1177/2050312118822927

Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80 . Medical Teacher . 2013;35(8):e1365-e1379. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977

Salkind NJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Research Design . Sage Publishing.

Shaughnessy JJ, Zechmeister EB, Zechmeister JS. Research Methods in Psychology . McGraw Hill Education.

By Anabelle Bernard Fournier Anabelle Bernard Fournier is a researcher of sexual and reproductive health at the University of Victoria as well as a freelance writer on various health topics.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

Published on 4 April 2022 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on 8 May 2023.

When collecting and analysing data, quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings. Both are important for gaining different kinds of knowledge.

Common quantitative methods include experiments, observations recorded as numbers, and surveys with closed-ended questions. Qualitative research Qualitative research is expressed in words . It is used to understand concepts, thoughts or experiences. This type of research enables you to gather in-depth insights on topics that are not well understood.

Table of contents

The differences between quantitative and qualitative research, data collection methods, when to use qualitative vs quantitative research, how to analyse qualitative and quantitative data, frequently asked questions about qualitative and quantitative research.

Quantitative and qualitative research use different research methods to collect and analyse data, and they allow you to answer different kinds of research questions.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Quantitative and qualitative data can be collected using various methods. It is important to use a data collection method that will help answer your research question(s).

Many data collection methods can be either qualitative or quantitative. For example, in surveys, observations or case studies , your data can be represented as numbers (e.g. using rating scales or counting frequencies) or as words (e.g. with open-ended questions or descriptions of what you observe).

However, some methods are more commonly used in one type or the other.

Quantitative data collection methods

- Surveys : List of closed or multiple choice questions that is distributed to a sample (online, in person, or over the phone).

- Experiments : Situation in which variables are controlled and manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Observations: Observing subjects in a natural environment where variables can’t be controlled.

Qualitative data collection methods

- Interviews : Asking open-ended questions verbally to respondents.

- Focus groups: Discussion among a group of people about a topic to gather opinions that can be used for further research.

- Ethnography : Participating in a community or organisation for an extended period of time to closely observe culture and behavior.

- Literature review : Survey of published works by other authors.

A rule of thumb for deciding whether to use qualitative or quantitative data is:

- Use quantitative research if you want to confirm or test something (a theory or hypothesis)

- Use qualitative research if you want to understand something (concepts, thoughts, experiences)

For most research topics you can choose a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach . Which type you choose depends on, among other things, whether you’re taking an inductive vs deductive research approach ; your research question(s) ; whether you’re doing experimental , correlational , or descriptive research ; and practical considerations such as time, money, availability of data, and access to respondents.

Quantitative research approach

You survey 300 students at your university and ask them questions such as: ‘on a scale from 1-5, how satisfied are your with your professors?’

You can perform statistical analysis on the data and draw conclusions such as: ‘on average students rated their professors 4.4’.

Qualitative research approach

You conduct in-depth interviews with 15 students and ask them open-ended questions such as: ‘How satisfied are you with your studies?’, ‘What is the most positive aspect of your study program?’ and ‘What can be done to improve the study program?’

Based on the answers you get you can ask follow-up questions to clarify things. You transcribe all interviews using transcription software and try to find commonalities and patterns.

Mixed methods approach

You conduct interviews to find out how satisfied students are with their studies. Through open-ended questions you learn things you never thought about before and gain new insights. Later, you use a survey to test these insights on a larger scale.

It’s also possible to start with a survey to find out the overall trends, followed by interviews to better understand the reasons behind the trends.

Qualitative or quantitative data by itself can’t prove or demonstrate anything, but has to be analysed to show its meaning in relation to the research questions. The method of analysis differs for each type of data.

Analysing quantitative data

Quantitative data is based on numbers. Simple maths or more advanced statistical analysis is used to discover commonalities or patterns in the data. The results are often reported in graphs and tables.

Applications such as Excel, SPSS, or R can be used to calculate things like:

- Average scores

- The number of times a particular answer was given

- The correlation or causation between two or more variables

- The reliability and validity of the results

Analysing qualitative data

Qualitative data is more difficult to analyse than quantitative data. It consists of text, images or videos instead of numbers.

Some common approaches to analysing qualitative data include:

- Qualitative content analysis : Tracking the occurrence, position and meaning of words or phrases

- Thematic analysis : Closely examining the data to identify the main themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying how communication works in social contexts

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2023, May 08). Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/quantitative-qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

The differences between qualitative and quantitative research methods

Last updated

15 January 2023

Reviewed by

Two approaches to this systematic information gathering are qualitative and quantitative research. Each of these has its place in data collection, but each one approaches from a different direction. Here's what you need to know about qualitative and quantitative research.

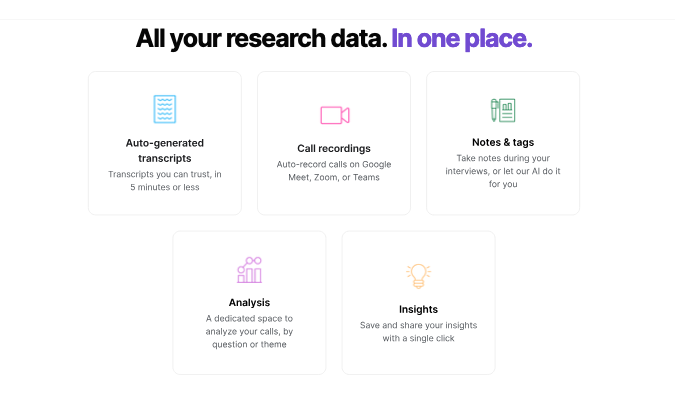

All your data in one place

Analyze your qualitative and quantitative data together in Dovetail and uncover deeper insights

- The differences between quantitative and qualitative research

The main difference between these two approaches is the type of data you collect and how you interpret it. Qualitative research focuses on word-based data, aiming to define and understand ideas. This study allows researchers to collect information in an open-ended way through interviews, ethnography, and observation. You’ll study this information to determine patterns and the interplay of variables.

On the other hand, quantitative research focuses on numerical data and using it to determine relationships between variables. Researchers use easily quantifiable forms of data collection, such as experiments that measure the effect of one or several variables on one another.

- Qualitative vs. quantitative data collection

Focusing on different types of data means that the data collection methods vary.

Quantitative data collection methods

As previously stated, quantitative data collection focuses on numbers. You gather information through experiments, database reports, or surveys with multiple-choice answers. The goal is to have data you can use in numerical analysis to determine relationships.

Qualitative data collection methods

On the other hand, the data collected for qualitative research is an exploration of a subject's attributes, thoughts, actions, or viewpoints. Researchers will typically conduct interviews , hold focus groups, or observe behavior in a natural setting to assemble this information. Other options include studying personal accounts or cultural records.

- Qualitative vs. quantitative outcomes

The two approaches naturally produce different types of outcomes. Qualitative research gains a better understanding of the reason something happens. For example, researchers may comb through feedback and statements to ascertain the reasoning behind certain behaviors or actions.

On the other hand, quantitative research focuses on the numerical analysis of data, which may show cause-and-effect relationships. Put another way, qualitative research investigates why something happens, while quantitative research looks at what happens.

- How to analyze qualitative and quantitative data

Because the two research methods focus on different types of information, analyzing the data you've collected will look different, depending on your approach.

Analyzing quantitative data

As this data is often numerical, you’ll likely use statistical analysis to identify patterns. Researchers may use computer programs to generate data such as averages or rate changes, illustrating the results in tables or graphs.

Analyzing qualitative data

Qualitative data is more complex and time-consuming to process as it may include written texts, videos, or images to study. Finding patterns in thinking, actions, and beliefs is more nuanced and subject to interpretation.

Researchers may use techniques such as thematic analysis , combing through the data to identify core themes or patterns. Another tool is discourse analysis , which studies how communication functions in different contexts.

- When to use qualitative vs. quantitative research

Choosing between the two approaches comes down to understanding what your goal is with the research.

Qualitative research approach

Qualitative research is useful for understanding a concept, such as what people think about certain experiences or how cultural beliefs affect perceptions of events. It can help you formulate a hypothesis or clarify general questions about the topic.

Quantitative research approach

On the other hand, quantitative research verifies or tests a hypothesis you've developed, or you can use it to find answers to those questions.

Mixed methods approach

Often, researchers use elements of both types of research to provide complex and targeted information. This may look like a survey with multiple-choice and open-ended questions.

- Benefits and limitations

Of course, each type of research has drawbacks and strengths. It's essential to be aware of the pros and cons.

Qualitative studies: Pros and cons

This approach lets you consider your subject creatively and examine big-picture questions. It can advance your global understanding of topics that are challenging to quantify.

On the other hand, the wide-open possibilities of qualitative research can make it tricky to focus effectively on your subject of inquiry. It makes it easier for researchers to skew the data with social biases and personal assumptions. There’s also the tendency for people to behave differently under observation.

It can also be more difficult to get a large sample size because it's generally more complex and expensive to conduct qualitative research. The process usually takes longer, as well.

Quantitative studies: Pros and cons

The quantitative methodology produces data you can communicate and present without bias. The methods are direct and generally easier to reproduce on a larger scale, enabling researchers to get accurate results. It can be instrumental in pinning down precise facts about a topic.

It is also a restrictive form of inquiry. Researchers cannot add context to this type of data collection or expand their focus in a different direction within a single study. They must be alert for biases. Quantitative research is more susceptible to selection bias and omitting or incorrectly measuring variables.

- How to balance qualitative and quantitative research

Although people tend to gravitate to one form of inquiry over another, each has its place in studying a subject. Both approaches can identify patterns illustrating the connection between multiple elements, and they can each advance your understanding of subjects in important ways.

Understanding how each option will serve you will help you decide how and when to use each. Generally, qualitative research can help you develop and refine questions, while quantitative research helps you get targeted answers to those questions. Which element do you need to advance your study of the subject? Can both of them hone your knowledge?

Open-ended vs. close-ended questions

One way to use techniques from both approaches is with open-ended and close-ended questions in surveys. Because quantitative analysis requires defined sets of data that you can represent numerically, the questions must be close-ended. On the other hand, qualitative inquiry is naturally open-ended, allowing room for complex ideas.

An example of this is a survey on the impact of inflation. You could include both multiple-choice questions and open-response questions:

1. How do you compensate for higher prices at the grocery store? (Select all that apply)

A. Purchase fewer items

B. Opt for less expensive choices

C. Take money from other parts of the budget

D. Use a food bank or other charity to fill the gaps

E. Make more food from scratch

2. How do rising prices affect your grocery shopping habits? (Write your answer)

We need qualitative and quantitative forms of research to advance our understanding of the world. Neither is the "right" way to go, but one may be better for you depending on your needs.

Learn more about qualitative research data analysis software

Should you be using a customer insights hub.

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

763k Accesses

364 Citations

90 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

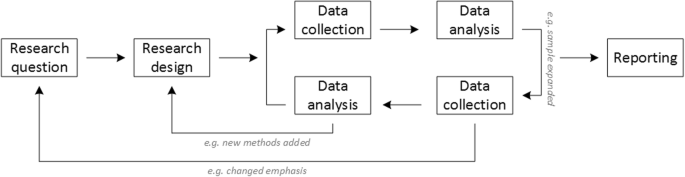

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

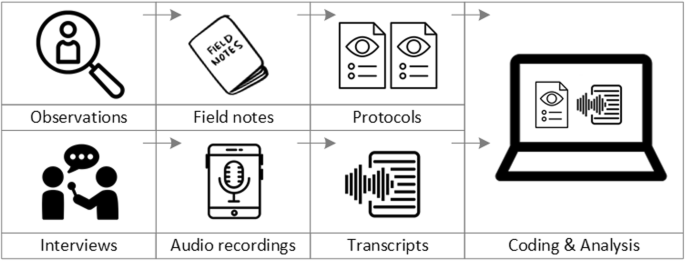

Data collection

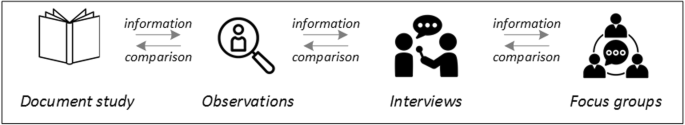

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews