- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Currently reading: Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG

- Business school teaching case study: what does climate change mean for home insurance?

- Business school teaching case study: can biodiversity bonds save natural habitats?

- Business school teaching case study: can the fashion industry be more sustainable?

- Business school teaching case study: can green hydrogen’s potential be realised?

- Business school teaching case study: how electric vehicles pose tricky trade dilemmas

- Business school teaching case study: is private equity responsible for child labour violations?

Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on x (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on facebook (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Gabriela Salinas and Jeeva Somasundaram

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In April this year, Hein Schumacher, chief executive of Unilever, announced that the company was entering a “new era for sustainability leadership”, and signalled a shift from the central priority promoted under his predecessor , Alan Jope.

While Jope saw lack of social purpose or environmental sustainability as the way to prune brands from the portfolio, Schumacher has adopted a more balanced approach between purpose and profit. He stresses that Unilever should deliver on both sustainability commitments and financial goals. This approach, which we dub “realistic sustainability”, aims to balance long- and short-term environmental goals, ambition, and delivery.

As a result, Unilever’s refreshed sustainability agenda focuses harder on fewer commitments that the company says remain “very stretching”. In practice, this entails extending deadlines for taking action as well as reducing the scale of its targets for environmental, social and governance measures.

Such backpedalling is becoming widespread — with many companies retracting their commitments to climate targets , for example. According to FactSet, a US financial data and software provider, the number of US companies in the S&P 500 index mentioning “ESG” on their earnings calls has declined sharply : from a peak of 155 in the fourth quarter 2021 to just 29 two years later. This trend towards playing down a company’s ESG efforts, from fear of greater scrutiny or of accusations of empty claims, even has a name: “greenhushing”.

Test yourself

This is the fourth in a series of monthly business school-style teaching case studies devoted to the responsible business dilemmas faced by organisations. Read the piece and FT articles suggested at the end before considering the questions raised.

About the authors: Gabriela Salinas is an adjunct professor of marketing at IE University; Jeeva Somasundaram is an assistant professor of decision sciences in operations and technology at IE University.

The series forms part of a wider collection of FT ‘instant teaching case studies ’, featured across our Business Education publications, that explore management challenges.

The change in approach is not limited to regulatory compliance and corporate reporting; it also affects consumer communications. While Jope believed that brands sold more when “guided by a purpose”, Schumacher argues that “we don’t want to force fit [purpose] on brands unnecessarily”.

His more nuanced view aligns with evidence that consumers’ responses to the sustainability and purpose communication attached to brand names depend on two key variables: the type of industry in which the brand operates; and the specific aspect of sustainability being communicated.

In terms of the sustainability message, research in the Journal of Business Ethics found consumers can be less interested when product functionality is key. Furthermore, a UK survey in 2022 found that about 15 per cent of consumers believed brands should support social causes, but nearly 60 per cent said they would rather see brand owners pay taxes and treat people fairly.

Among investors, too, “anti-purpose” and “anti-ESG” sentiment is growing. One (unnamed) leading bond fund manager even suggested to the FT that “ESG will be dead in five years”.

Media reports on the adverse impact of ESG controversies on investment are certainly now more frequent. For example, while Jope was still at the helm, the FT reported criticism of Unilever by influential fund manager Terry Smith for displaying sustainability credentials at the expense of managing the business.

Yet some executives feel under pressure to take a stand on environmental and social issues — in many cases believing they are morally obliged to do so or through a desire to improve their own reputations. This pressure may lead to a conflict with shareholders if sustainability becomes a promotional tool for managers, or for their personal social responsibility agenda, rather than creating business value .

Such opportunistic behaviours may lead to a perception that corporate sustainability policies are pursued only because of public image concerns.

Alison Taylor, at NYU Stern School of Business, recently described Unilever’s old materiality map — a visual representation of how companies assess which social and environmental factors matter most to them — to Sustainability magazine. She depicted it as an example of “baggy, vague, overambitious goals and self-aggrandising commitments that make little sense and falsely suggest a mayonnaise and soap company can solve intractable societal problems”.

In contrast, the “realism” approach of Schumacher is being promulgated as both more honest and more feasible. Former investment banker Alex Edmans, at London Business School, has coined the term “rational sustainability” to describe an approach that integrates financial principles into decision-making, and avoids using sustainability primarily for enhancing social image and reputation.

Such “rational sustainability” encompasses any business activity that creates long-term value — including product innovation, productivity enhancements, or corporate culture initiatives, regardless of whether they fall under the traditional ESG framework.

Similarly, Schumacher’s approach aims for fewer targets with greater impact, all while keeping financial objectives in sight.

Complex objectives, such as having a positive impact on the world, may be best achieved indirectly, as expounded by economist John Kay in his book, Obliquity . Schumacher’s “realistic sustainability” approach means focusing on long-term value creation, placing customers and investors to the fore. Saving the planet begins with meaningfully helping a company’s consumers and investors. Without their support, broader sustainability efforts risk failure.

Questions for discussion

Read: Unilever has ‘lost the plot’ by fixating on sustainability, says Terry Smith

Companies take step back from making climate target promises

The real impact of the ESG backlash

Unilever’s new chief says corporate purpose can be ‘unwelcome distraction ’

Unilever says new laxer environmental targets aim for ‘realism’

How should business executives incorporate ESG criteria in their commercial, investor, internal, and external communications? How can they strike a balance between purpose and profits?

How does purpose affect business and brand value? Under what circumstances or conditions can the impact of purpose be positive, neutral, or negative?

Are brands vehicles by which to drive social or environmental change? Is this the primary role of brands in the 21st century or do profits and clients’ needs come first?

Which categories or sectors might benefit most from strongly articulating and communicating a corporate purpose? Are there instances in which it might backfire?

In your opinion, is it necessary for brands to take a stance on social issues? Why or why not, and when?

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here .

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Promoted Content

Explore the series.

Follow the topics in this article

- Sustainability Add to myFT

- Impact investing Add to myFT

- Corporate governance Add to myFT

- Corporate social responsibility Add to myFT

- Business school case Add to myFT

Sustainability as Opportunity: Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan

- First Online: 08 March 2018

Cite this chapter

- Joanne Lawrence 4 ,

- Andreas Rasche 5 &

- Kevina Kenny 6

162k Accesses

9 Citations

8 Altmetric

Sustainability, as it relates to both social and environmental issues, is treated very differently among companies that incorporate the subject into their business strategies. In this case, we explore sustainability at Unilever whose management addresses it not as a risk to be managed or cost to be avoided, but as an opportunity for competitive advantage and growth. With emerging markets as the backdrop, we learn about Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan, and what the company has done to integrate sustainability principles into its business model and build on its core competencies, such as innovative product development and marketing expertise, to realise the potential of the fast-growing emerging markets (57% of its 2014 revenues came from emerging markets compared to less than 17% of most multinationals). Issues considered are the role of corporate culture and competencies, the importance of committed and courageous leadership, the willingness to set ambitious goals, and the challenge of creating internal and external alignment around strategic goals.

This case was developed with assistance from Hult EMBA student Kevina Kenny and with the generous help of Gail Klintworth, former Chief Sustainability Officer at Unilever and Karen Hamilton, Vice President of Sustainable Business, who kindly shared their unique perspectives and keen insights with us. Developed originally as part of an Executive Series intended to initiate discussions by Boards of Directors, such as those participating in the UN Global Compact LEAD/PRME Program, and senior managers on critical issues of the day, both the original (2013) and its revision (2015) are published by Hult International Business School. Used with permission.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: The Sustainable Development Goals and the Future of Corporate Sustainability

Sustainable Business Models: Theoretical Reflections

CSR Europe: Sustainability and Business

The World Bank, Multipolarity: The New Global Economy Global Development Horizons 2011. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGDH/Resources/GDH_CompleteReport2011.pdf , Overview, p.3.

Atsmon, Yuval, Peter Child, Richard Dobbs and Laxman Narasimhan, Winning the $30 Trillion Decathlon: Going for Gold in Emerging Markets, McKinsey Quarterly, August 2012. Retrieved from www.mckinsey.com/features/30_trillion_decathalon .

Stewart, Heather and Larry Elliot, Nicholas Stern:’ I Got it Wrong on Climate Change: It is Far, Far worse’, The Guardian, January 27, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/jan/27/nicholas-stern-climate-change-davos .

The Global Environment Facility, 2009.Land Degradation Fact Sheet, June 2009. Retrieved from http://www.thegef.org/gef/node/2833 .

PwC, Green Products: Using Sustainable Attributes to Drive Growth and Value. Sustainable Business Solutions, December 15. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.pwc.com/us/en/corporate-sustainability-climate change/publications/green-products-paper.html.

Atsmon et al.

Unilever plc. Retrieved from http://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/ourapproach/ourcompassstrategy/

Unilever plc. Retrieved from http://www.unilever.com/aboutus/introductiontounilever/ ourmission

Ignatius, Adi, June 2012: Captain Planet: An Interview with Unilever CEO Paul Polman , Harvard Business Review, June 2012. Retrieved from http://hbr.org/2012/06/captain-planet/ .

Unilever plc. Retrieved from http://www.unilever.com/aboutus/introductiontounilever/ ourmission.

Unilever Sustainable Living Plan. Retrieved from unilever.com/sustainable-living/uslp .

Unilever plc. Retrieved from www.unilever.com/aboutus/introductiontounilever/ .

Unilever plc. Retrieved from https://foundry.unilever.com /.

Pingali, Prabhu, Who is the Smallholder Farmer? Retrieved from http://www.worldfoodprize.org/documents/filelibrary/documents/borlaugdialogue2010_/2010transcripts/2010_Borlaug_Dialogue_Who_Is_the_Sm_70428DF38B8BD.pdf ; Unilever plc. Annual Report 2014, p.26. Retrieved from http://www.unilever.com/investor-relations/annual-reports-and-accounts/annual-report-and-accounts-2014/ .

Unilever plc. Annual Report 2013, p. 12. Retrieved from http: www.unilever.com/investor-relations/annual-reports-and-accounts 2013.

Unilever plc. www.unilever.com/Images/uslp-Unilever-Sustainable-Living-Plan-Scaling-for-Impact-Summary-of-progress-2014_tcm244-424809.pdf , p.11.

Interview with Karen Hamilton, Vice President, Sustainable Business, Unilever plc, August 7, 2015.

John Maguire, Group Manufacturing Sustainability Director, Unilever, plc. Reducing Emissions in Our Own Operations, Retrieved September 16, 2015, https://www.unilever.com/sustainab le-living/the-sustainable-living-plan/reducing-environmental-impact/greenhouse-gases/Reducing-emissions-in-our-own-operations.

Unilever plc. www.unilever.com/Images/uslp-Unilever-Sustainable-Living-Plan-Scaling-for-Impact-Summary-of-progress-2014_tcm244-424809.pdf , p.10.

Boynton, Andy and Margareta Barchan, Unilever’s Paul Polman: CEOs Can’t Be ‘Slaves’ to Shareholders, Forbes, July 20, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/andyboynton/2015/07/20/unilevers-paul-polman-ceos-cant-be-slaves-to-shareholders .

Unilever, plc. Retrieved from http. www.unilever.com/mediacentre/pressreleases/2013/UnileverSustainableLivingPlanhelping todrivegrowth.aspx.

Unilever plc. Retrieved from http://www.unilever.com/about us/ourhistory.

Unilever plc. Randomised Clinical Trial, 2000 Families, Mumbai 2007–2008. Retrieved from http: www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/healthandhygiene/handwashing/handwashingbehaviourchange/index.aspx .

Unilever plc. Annual Report 2014, p. 28. Retrieved from http://www.unilever.com/investor-relations/annual-reports-and-accounts/annual-report-and-accounts-2014 .

Fighting for the Next Billion Shoppers . The Economist, June 30 2012. Retrieved from http://economist.com/nodel/21557815 .

Unilever plc. Annual Report 2014, p.28. Retrieved from http://www.unilever.com/investor-relations/annual-reports-and-accounts/annual-report-and-accounts-2014/ .

Unilever plc. Annual Report 2014, p.28. Retrieved from http://www.unilever.com/investor-relations/annual-reports-and-accounts/annual-report-and-accounts-2014 .

Unilever’s Five Levers of Change. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?jEaGM8kDac4 .

Unilever plc. www.unilever.com/Images/up-Unilever-Sustainable-Living-Plan-Scaling-for-Impact-Summary-of-progress-2014_tcm244-424809.pdf, p.5.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hult International Business School, Cambridge, MA, USA

Joanne Lawrence

Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark

Andreas Rasche

Hult International Business School EMBA, Cambridge, MA, USA

Kevina Kenny

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joanne Lawrence .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

ABIS, The Academy of Business in Society, Brussels, Belgium

Gilbert G. Lenssen

INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France

N. Craig Smith

INSEAD, Singapore, Singapore

Appendix 1: Unilever’s Business Model: A Virtuous Circle of Growth

Our virtuous circle of growth describes how we generate profit from our sustainable growth business model.

Making sustainable living commonplace for our consumers is helping to drive profitable growth. By focusing on sustainable living needs, we can build brands with a significant purpose. By reducing waste and material use, we create efficiencies and cut costs. This helps to improve our margins. By looking at product development, sourcing and manufacturing through a sustainability lens, opportunities for innovation open up. And we have found that by collaborating with partners including not-for-profit organisations, we gain valuable new market insights and extend channels to engage with consumers.

Source: http://www.unilever.com/Images/uslp-Unilever-Sustainable-Living-Plan-Scaling-for-Impact-Summary-of-progress-2014_tcm244-424809.pdf (p. 14).

Appendix 2: Unilever’s Governance of Sustainability and Corporate Responsibility

Committee | Description |

|---|---|

Unilever Leadership Executive | The Executive, led by the CEO, has responsibility for operational leadership of the business. The Executive has also overall responsibility for sustainability and corporate responsibility. |

Corporate Responsibility Committee | Board committee consisting of Non-Executive Directors. This committee ensures compliance with the Code of Business Principles and oversees progress and potential risk regarding the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan. One of its priorities is to ensure that the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan is maintained through appropriate business strategies. The committee feeds back to the Board. |

Unilever Sustainable Living Plan Steering Team | Chaired by the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO), contains senior leaders from a variety of corporate functions supporting the Unilever Leadership Executive. The team meets five times a year and is accountable for driving sustainable growth, and keeping the Board informed of emerging trends and potential risks associated with sustainability issues. |

Unilever Sustainable Living Plan Council | Group of six independent external experts who advise and comment on progress regarding the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan and strategy. |

Audit Committee | Board committee overseeing independent assurance with regard to the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan. |

Global Code and Policy Committee | Chaired by the Chief Legal Officer, this committee oversees the implementation of Unilever’s Code of Business Principles. |

Specialized Group: Sustainable Agriculture Steering Group | This group promotes sustainable supply chains and takes advice from Unilever’s Sustainable Sourcing Board of external experts. |

Specialized Group: Safety and Environmental Assurance Centre (SEAC) | SEAC provides independent scientific evidence to help Unilever manage risk and environmental impact, including the development of relevant metrics and baseline measures (e.g., for environmental assessments). |

- Source: Unilever Annual Report, 2014, p. 66

Appendix 3: The Unilever Sustainable Living Plan: From Seven (2010) to Nine Commitments (2013)

Commitment | Goal | Progress (2010–2014) |

|---|---|---|

1. Health and hygiene | By 2020 we will help more than a billion people to improve their hygiene habits and we will bring safe drinking water to 500 million people. This will help reduce the incidence of life-threatening diseases like diarrhea. | 397 million people reached through handwashing, sanitation, safe drinking water, oral health and self-esteem programmes (e.g., Lifebuoy handwashing campaign helped to reduce diarrhea and respiratory diseases, reaching 257 million people in 16 countries). |

2. Nutrition | By 2020 we will double the proportion of our portfolio that meets the highest nutritional standards, based on globally recognized dietary guidelines. This will help hundreds of millions of people to achieve a healthier diet. | 33% of portfolio by volume met the criteria for highest nutritional standards. (e.g., salt, saturated fat). |

3. Greenhouse gases | Halve the greenhouse gas impact of our products across the lifecycle by 2020. | Greenhouse gas impact per consumer use increased by around 4% since 2010. |

4. Water | Halve the water associated with the consumer use of our products by 2020. | Water impact per consumer use reduced by 2% since 2010 (e.g., laundry, washing). |

5. Waste | Halve the waste associated with the disposal of our products by 2020. | Waste impact per consumer use reduced by around 12% since 2010. |

6. Sustainable sourcing | By 2020 we will source 100% of our agricultural raw materials sustainably. | 55% of agricultural raw materials sourced sustainably by end 2014 (e.g., 100% of palm oil; 87% of Lipton yellow tag tea sourced from Rainforest Alliance certified growers). |

7. Fairness in the workplace | By 2020 we will advance human rights across our operations and extended supply chain. | 85% of 200 key suppliers meet company’s mandatory responsible sourcing criteria. |

8. Opportunities for women | By 2020 we will empower 5 million women. | Empowered 238,000 women, including training 70,000 Shakti micro-entrepreneurs in rural India to sell Unilever products. |

9. Inclusive business | By 2020 we will have a positive impact on 5.5 million people. | Working in partnership, 800,000 smallholder farmers gain access to training and support. |

- Source: http://www.unilever.com/Images/uslp-Unilever-Sustainable-Living-Plan-Scaling-for-Impact-Summary-of-progress-2014_tcm244-424809.pdf p.20–21; https://www.unilever.com/Images/ir_Unilever_AR14_tcm244-421557.pdf , p.11

- Note: In 2013, Unilever’s management increased the original seven Commitments of the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan to nine. The orginal seventh Commitment – Enhancing livelioods – was expanded to encompass more human rights issues, such as ensuring fair compensation, healthy and safe working conditions, and employee development, to more specificaly target women by upholding diverity and offering them opportunties, and to focus on bringing more people into the economy by helping to train and support smallholder farmers in particular.

Appendix 4: Unilever Sustainable Living Plan and the ESG Value Driver Framework

The ESG (Economic, Social and Governance) Value Driver Framework was developed by the Principles of Responsible Investment Management and the UN Global Compact to help companies communicate how sustainability- related actions link with business benefits. Following are examples from Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan Reports for 2012–2014.

Growth | New markets and geographies | Gain access to new markets and geographies through exposure from ESG programmes | In 2012, efforts to save greenhouse gases by reducing hot water usage led to the successful rollout of dry shampoos in ten countries; use of “green”’ refrigeration won over major new retail customers in Denmark to carry Unilever products. |

New customers and market share | Use ESG programmes to engage customers and build knowledge of expectations and behavior | Oral health campaign reached 50 million people between 2008 and 2012 and has led to increased toothpaste sales: e.g., Signal toothpaste up more than 22% since 2008, and helped to introduce the toothpaste into new markets, such as Cote d’Ivoire. | |

Dove soap’s “Free Being Me”’ campaign to build girls’ self-esteem grew from 20 countries to more than 70 in 2014, increasing brand loyalty and revenues. | |||

In emerging markets, brands integrating sustainability such as Dove, Lifebuoy and Domestos grew faster than average. | |||

Product and services innovation | Develop cutting edge technology and innovative products and services for unmet social or environmental needs | R+D efforts to reduce consumers’ water usage in water-stressed areas led to Lifebuoy Foam Handwash and Comfort One Rinse for laundry; to reduce waste and emissions, new packaging materials developed (bi-modal resins) that lighten weight and save shipping costs; waived exclusive rights to package-saving technology for Dove bottle that uses 15% less plastic to encourage other companies to use the technology; re-engineered aerosol spray system so that new compressed deodorant cans use half the propellant gas and 25% less aluminum than traditional cans, reducing carbon footprint by 25%. | |

Long-term strategy | Develop long-term strategy encompassing all ESG issues and shape material ESG communication based on value-driver framework | Unilever Sustainable Living Plan encompasses ESG elements and is integrated into strategy, operations and governance; human rights recently integrated more explicitly; company has a zero tolerance policy on forced labour, and trains employees on human trafficking prevention. Progress against financial and non-financial targets are included in annual report. | |

Return on capital | Operational efficiency | Enable bottom line cost savings through environmental operations and practices (e.g., energy, water, waste efficiency, less raw materials used) | Eco-efficiency programme addressing water, waste, energy and materials has avoided costs of €400 million since 2008; coordinating transport, managing logistics and using lower emissions vehicles has resulted in additional savings. By January 2015, greater focus on eco-production led to all 240 factories achieving zero non-hazardous waste to landfill. |

Human capital management | Attract and retain better and highly motivated employees by positioning company and management as ESG leaders | Ensures that “employer brand” has sustainability at its core: voted No.1 FMCG employer of choice among graduates from 32 countries. | |

Facebook global careers page has attracted 100,000+ likes. Third most in-demand employer on LinkedIn’s global in Demand index, only behind Apple and Google. Two million job applications received in 2014. | |||

Engages employees regularly: 2014 Global People Survey had 75% engagement score – in line with high-performing employers in class. | |||

Reputational pricing power | Develop brand loyalty and reputation through ESG efforts that garners customers’ willingness to pay price increases or premium | In consumer marketing, the effect of multiple touch points helps to create pricing power. Unilever seeks ways in which its holistic activities–, of which sustainability is a key part – are affecting consumers’ loyalty. E.g., Kissan ketchup focused Indian consumers on its 100% real ingredients, propelling the brand to market leadership; Knorr s first ever ‘on pack’ sustainability logo improved its brand equity in Germany. | |

Risk management | Operational and regulatory risk | Mitigate risk by complying with regulatory requirements and industry standards by addressing ESG issues in policies, systems and standards and engaging with employees | Unilever helped found industry wide initiatives such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and Marine Stewardship Council to set standards for these critical resources. It ranked first of 152 companies in combating deforestation by the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), securing its supply chain. |

Reputational risk | Facilitate uninterrupted operations and entry into new markets using local ESG efforts and community dialogue to engage citizens and reduce local resistance; avoid negative media publicity and NGO boycotts by addressing ESG issues | Unilever engages with local constituents regularly, building trust and reputation (e.g., partnering with governments and NGOs in its “Help a Child Reach Five” handwashing campaign; with UNICEF and water and deforestation initiatives.) Sector leader in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI); ranked No. 1 by Globescan/SustainAbility as sustainability leader for the fifth year. | |

Supply chain risk | Secure consistent and long-term access to high-quality raw materials and products by engaging in supply chain community welfare and development | Working with smallholder farmers and local distributors to develop sustainable agricultural practices; ensuring traceability of raw materials (e.g., palm oil, soy, tea and cocoa) helps to secure supplies; its Responsible Sourcing Policy requires suppliers to comply with such principles as fair compensation, voluntary employment, and health and safety standards, and, in some cases, to submit to third party audits. | |

Leadership and adaptability | Develop leadership skills and culture to adapt to fast changing political, social and environmental situations | The Sustainable Living Plan is incorporated into management training and compensations programmes; the company offers flexible working hours, job sharing, maternity and paternity leave (women up to 43% workforce in 2014) to attract and retain women. |

- Source: Unilever Sustainable Living Plan Report 2012; Annual Report, Sustainable Living Report, 2014

Appendix 5: Consolidated Income Statement and Key Indicators Since USLP Launch

Statement of comprehensive income | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Turnover (€ million) | 44,262 | 46,467 | 51,324 | 49,797 | 48,436 |

Operating profit (€ million) | 6325 | 6420 | 6977 | 7517 | 7980 |

Core operating profit (€ million) | 6017 | 6276 | 7050 | 7016 | 7020 |

Profit before tax (€ million) | 5951 | 6066 | 6533 | 7114 | 7646 |

Net profit (€ million) | 4465 | 4491 | 4836 | 5263 | 5515 |

Diluted earnings per share (€) | 1.42 | 1.42 | 1.50 | 1.66 | 1.79 |

Core earnings per share* (€) | 1.31 | 1.37 | 1.53 | 1.58 | 1.61 |

Key financial performance indicators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

Underlying sales growth (%) | 4.1 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 4.3 | 2.9 |

Underlying volume growth (%) | 5.8 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

Core operating margin (%) | 13.6 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 14.1 | 14.5 |

Free cash flow (€ million) | 3365 | 3075 | 4333 | 3856 | 3100 |

Non-financial indicators | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2012 (1) | 2013 (1) (2) | 2014 (1) (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CO2 from energy (kg/tonne of production) | 133.59 | 118.31 | 99.97 | 104.23 | 98.85 | 92.02 |

Water usage (m3/tonne of production) | 2.68 | 2.4 | 2.23 | 2.27 | 2.12 | 2.01 |

Total waste sent for disposal (kg/tonne of production) | 6.48 | 4.96 | 3.85 | 3.94 | 2.27 | 1.19 |

Total recordable accident frequency rate (TRFR) per 1,000,000 h | 1.63 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.17 | 1.03 | 1.05 |

(1) In 2013 we adjusted our reporting period from 1 January – 31 December to 1 October – 30 September. We also show the prior 12 months to enable a like-for-like comparison, presented as 12(1). (2) PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) assured | ||||||

For details and the basis of preparation see: |

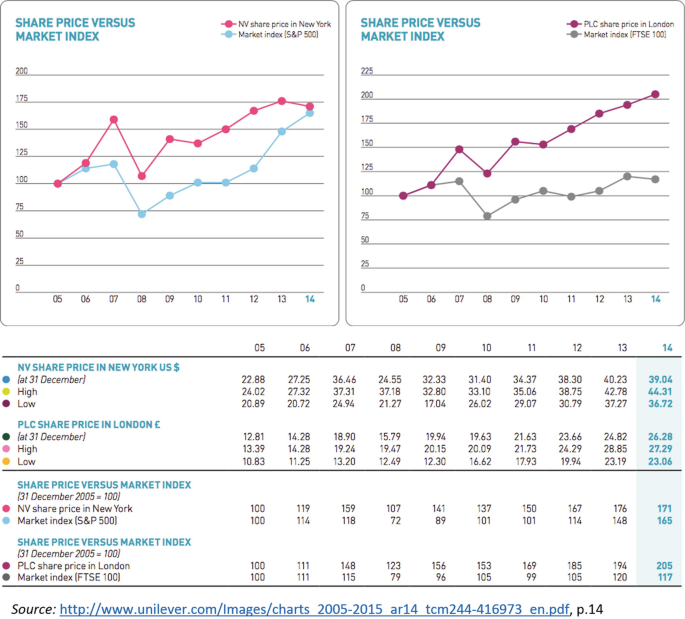

- Source: http://www.unilever.com/Images/charts_2005-2015_ar14_tcm244-416973_en.pdf

Appendix 6: Share Price Versus Market Index

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Lawrence, J., Rasche, A., Kenny, K. (2019). Sustainability as Opportunity: Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan. In: Lenssen, G.G., Smith, N.C. (eds) Managing Sustainable Business. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1144-7_21

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1144-7_21

Published : 08 March 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-024-1142-3

Online ISBN : 978-94-024-1144-7

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Netherlands

Switzerland

United Kingdom

United States

Location not listed

Investments

Investment capabilities, other vehicles, have questions, more perspectives & research, select a location, making progress toward sustainability: a unilever case study.

The business case for how Unilever, a consumer products company, rethinks packaging, nutrition and governance.

Key Takeaways

Unilever, a top consumer products company, became a major polluter by selling products in single-use packaging.

The company has taken steps to minimize packaging or transform it into compostable forms to reduce waste.

While some Unilever food products aren’t very healthy, the firm has improved the nutrition of other offerings by reducing salt and sugar content.

Global greenhouse gas emissions and coal demand broke records in 2022.

What does that say about the trillions of dollars directed at sustainable investment strategies since 2019?

For one thing, we believe it highlights a shortcoming of many sustainability strategies: They often invest in companies that have already achieved significant progress in meeting sustainability goals while excluding those that haven’t.

American Century Investments’ Global Value Transition * strategy takes a different approach by engaging with companies to drive their business model progression. We believe sustainable investing can better achieve real-world outcomes by helping guide companies on their journeys to sustainability instead of rewarding those that have already arrived.

Unilever is one such company. In our view, this global producer of consumer and food products, renowned for brands such as Dove ® Chocolate and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, stands out for its advancements in environmental practices, social initiatives and governance standards.

Sustainable Solutions for Consumer Products

By their very nature, consumer products like a bottle of soap or a carton of ice cream lend themselves to single-use packaging. If the packaging can’t be composted or recycled, it ends up in a landfill or elsewhere. As one of the world’s largest consumer products companies, Unilever has contributed significantly to waste pollution through its packaging.

A 2019 report by Break Free From Plastic, a non-governmental organization advocating for reduced plastics use, claimed Unilever ranked as the fifth largest polluter from single-use plastics in an audit that covered 484 brands in 51 countries.

That same year, Unilever announced plans to cut the amount of virgin plastics used in its packaging with a goal of removing 100,000 tons of plastic by 2025.

Our measurements show Unilever’s progress with packaging materials. In 2022, 55% of its packaging was recyclable or compostable, up 5% since 2019.

Reducing plastic use has clear environmental benefits and hasn’t come at a cost to Unilever’s bottom line. Sales grew 15% from 2019 to 2022. We believe that as consumers become more conscious of the environment and the impacts of their buying decisions on the world around them, they will become more keen on buying from companies with better environmental performance.

Cutting back on plastic may also help reduce legal and regulatory risks.

For example, the New York attorney general sued PepsiCo in November 2023 for allegedly causing widespread plastic pollution in the Buffalo River that threatens water quality and wildlife. This action came after regulators collected trash at 13 spots along the river and found that Pepsi-related products accounted for the highest proportion of the waste. 1

Purported greenwashing was the focus of a recent complaint the European Consumer Organization and its member affiliates filed with the European Commission. The complaint targets Coca-Cola, Nestle and Danone for allegedly making misleading claims about their bottled water packaging. The consumer protection group disputes the companies’ assertions of “100% recyclable” or “100% recycled,” further stating that the use of green imagery “may even give the impression that the bottles would have a positive impact on the environment.” 2

We believe avoiding legal and regulatory actions like these would benefit the environment and the company’s financial performance.

Healthier Food Options for Conscious Consumers

About one-third of Unilever’s business includes food products ranging from ice cream to mayonnaise. If not enjoyed in moderation, these foods aren’t particularly healthy.

In recent years, Unilever has moved toward healthier versions of its offerings. In 2020, Unilever said 61% of its foods met its “highest nutritional standards” based on globally recognized dietary guidelines, while 77% met its target for 5 grams of salt intake. 3

From a financial perspective, we believe offering healthier foods may insulate the company from the potential consequences of weight-loss drugs if the use of these medications becomes widespread.

New classes of weight loss drugs have shown promising results in treating obesity and other obesity-related conditions like kidney disease. Several publicly traded companies in industries ranging from food companies to medical device manufacturers have seen share prices decline on the apparent belief that these drugs could impair their business models.

Governance Reform and Strategic Decision-Making

In 2021, Unilever tried to buy GlaxoSmithKline’s consumer health division in a deal that made investors recoil. When the financial press caught wind of the $68 billion buyout offer, the deal’s structure caused a sell-off in Unilever stock, and analysts reacted with bewilderment about Unilever’s pursuit. 4

The proposal died under its own weight, but the matter didn’t end there. Led by activist investor Nelson Peltz, Unilever replaced its management team and part of its board of directors for considering a deal widely seen as a risky strategic decision. From a governance standpoint, taking that action demonstrated the company’s willingness to shield shareholders from transactions that could potentially dilute the company’s value.

Resilience Amid Economic Challenges

We believe these factors complement the company's durable and resilient business model. In our view, Unilever illustrates the potential that the Global Value Transition strategy seeks — companies progressing toward sustainability that may likely deliver results for shareholders.

Portfolio Manager

Senior Investment Analyst

Client Portfolio Manager

Discover more about our Global Value Transition capabilities.

Related insights.

Will the Fed's Rate Cut Be a Boon for Small-Cap Stocks?

SEP 19 | 2024

5 Questions About Investing in Small-Cap Stocks for 2024

SEP 16 | 2024

Economic Slowdown Slowly Emerges

SEP 13 | 2024

Effective August 15, 2024, Global Sustainable Value was renamed Global Value Transition.

Office of the New York State Attorney General, “Attorney General James Takes Historic Action Against PepsiCo for Endangering the Environment and Public Health with Plastic Pollution,” Press Release, November 15, 2023.

European Consumer Organization, “Consumer Groups Launch EU-Wide Complaint Against Major Water Bottle Producers for Greenwashing,” Press Release, November 7, 2023.

Unilever, “10 Years of the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan: Our Nutrition Journey,” May 2020.

Kit Rees, “’Please Don’t:’ Analysts Scorn Unilever’s Takeover Ambitions,” Bloomberg, January 17, 2022.

Many of American Century’s investment strategies incorporate sustainability factors, using environmental, social, and/or governance (ESG) data, into their investment processes in addition to traditional financial analysis. However, when doing so, the portfolio managers may not consider sustainability-related factors with respect to every investment decision and, even when such factors are considered, they may conclude that other attributes of an investment outweigh sustainability factors when making decisions for the portfolio. The incorporation of sustainability factors may limit the investment opportunities available to a portfolio, and the portfolio may or may not outperform those investment strategies that do not incorporate sustainability factors. ESG data used by the portfolio managers often lacks standardization, consistency, and transparency, and for certain companies such data may not be available, complete, or accurate.

Sustainable Investing Definitions:

Integrated: An investment strategy that integrates sustainability-related factors aims to make investment decisions through the analysis of sustainability factors alongside other financial variables in an effort to make more informed investment decisions. A portfolio that incorporates sustainability factors may or may not outperform those investment strategies that do not incorporate sustainability factors. Portfolio managers have ultimate discretion in how sustainability factors may impact a portfolio’s holdings, and depending on their analysis, investment decisions may not be affected by sustainability factors.

Sustainability Focused: A sustainability-focused investment strategy seeks to invest, under normal market conditions, in securities that meet certain sustainability-related criteria or standards in an effort to promote sustainable characteristics, in addition to seeking superior, long-term, risk-adjusted returns. Alternatively, or in addition to traditional financial analysis, the investment strategy may filter its investment universe by excluding certain securities, industry, or sectors based on sustainability factors and/or business activities that do not meet specific values or norms. A sustainability focus may limit the investment opportunities available to a portfolio. Therefore, the portfolio may underperform or perform differently than other portfolios that do not have a sustainability investment focus. Sustainability-focused investment strategies include but are not limited to exclusionary, positive screening, best-in-class, improvers, thematic, and impact approaches.

The opinions expressed are those of American Century Investments (or the portfolio manager) and are no guarantee of the future performance of any American Century Investments' portfolio. This material has been prepared for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.

References to specific securities are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended as recommendations to purchase or sell securities. Opinions and estimates offered constitute our judgment and, along with other portfolio data, are subject to change without notice.

No offer of any security is made hereby. This material is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation of any investment strategy or product described herein. This material is directed to professional/institutional clients only and should not be relied upon by retail investors or the public. The content of this document has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority.

Conducting sustainability audits to drive performance improvement and ensure data accuracy for reporting

Unilever has been the Food & Beverage super-sector sustainability leader on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) for 12 straight years. Launched in 1999, the Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes are the first global indexes tracking the financial performance of the leading sustainability-driven companies worldwide. Based on the cooperation of Dow Jones Indexes and SAM they provide asset managers with reliable and objective benchmarks to manage sustainability portfolios.

Investors perceive sustainability as a catalyst for enlightened and disciplined management and thus, DJSI is a crucial business success factor. Highly regarded by influential investors all over the world, the DJSI helps shape the increasingly popular sustainability-driven investment portfolios.

The Unilever Sustainable Living Plan is Unilever’s groundbreaking and ambitious roadmap to achieve its growth vision in a way that increases the social value of its brands while simultaneously reducing its environmental impact. Unilever will report its progress to achieving the goals set forth in the USLP and therefore Unilever wanted to ensure that the Sustainability data collected and reported by its manufacturing sites was accurate.

Our Approach

As a pilot exercise, ERM offered to extend its existing audit to a Unilever facility. This work involved completing a detailed review of the Environment, Health and Safety sustainability data that had been reported, and comparing this data to the situation on site. As a result, ERM made a series of recommendations which Unilever adopted.

The sustainability related audit took one day to complete and, following its success, has now become a standard process for all Unilever sites across the Americas. ERM’s involvement will enable sites to ensure the accuracy of the data collation and reporting.

As a long-term partner, ERM has completed 82 audits for Unilever in the last three years.

Benefits and Value

Integrating ERM’s recommendations on sustainability into Unilever’s existing audit program will help Unilever in:

- Reporting against its new sustainability goals

- Safeguarding the accuracy of EHS data being reported across the Americas

- Drive performance improvement

- Leveraging ERM’s experienced auditors

The DJSIs are the world's most important and widely-recognized indexes for tracking the performance of sustainability-driven companies. They are calculated and published by the Swiss investment boutique SAM Group in cooperation with Dow Jones Indexes

How can we help?

How can we help you? Contact us to discuss how we can help your organization.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Net Positive Manifesto

- Paul Polman

- Andrew Winston

Both practically and morally, corporate leaders can no longer sit on the sidelines of major societal shifts or treat human and planetary issues as “someone else’s problem.” For their own good, they must play an active role in addressing our biggest shared challenges. The economy won’t thrive unless people and the planet are thriving.

In this bold manifesto, consultant and author Andrew Winston and former Unilever CEO Paul Polman describe their vision of a “net positive” company—one that grows by helping the world flourish. Drawing on examples from Unilever and other leading companies, they outline four critical paths businesses can take to prosper today and win in the future. They can operate first in service of multiple stakeholders—which then benefits investors (as opposed to putting shareholders above all others); take full ownership of all company impacts; embrace deep partnerships, even with critics; and tackle systemic challenges by rethinking advocacy and the relationship with governments.

No company has yet reached the ambitious goal of becoming net positive. But a growing number have begun the journey—unlocking greater value for their businesses while helping solve larger problems for the benefit of all.

Is the world better off because your company is in it?

Idea in Brief

The problem.

Current efforts by business to address planetary challenges such as climate change are inadequate.

The Solution

Corporations should strive to become net positive, improving well-being for everyone they affect—every product, operation, and stakeholder, including future generations and the planet itself.

First Steps

No company is yet net positive. To get started, firms should think about stakeholders, not just shareholders; take full ownership of all company impacts; embrace partnerships and work with critics; and rethink their approach to lobbying and other forms of advocacy.

Society’s expectations of business have changed more in the past two years than in the previous 20. A pandemic, expanding and ever-more-expensive natural disasters, George Floyd’s murder, attacks on democracy, and more: All moved us past a tipping point. Both practically and morally, corporate leaders can no longer sit on the sidelines of major societal shifts or treat human and planetary issues as “someone else’s problem.” For their own good, companies must play an active role in solving our biggest shared challenges. The economy won’t thrive unless people and the planet are thriving.

- Paul Polman was the CEO of Unilever from 2009 to 2019 and helped develop the UN Global Goals. He is a coauthor of Net Positive .

- Andrew Winston is one of the world’s leading thinkers on sustainable business strategy. His books include Green to Gold , The Big Pivot , and Net Positive . AndrewWinston

Partner Center

Unilever East & West Africa Change location

Addressing the climate crisis: a unified approach from business and government

Published: 25 September 2024

Combating climate change needs business and government collaboration. Our CEO Hein Schumacher and former UNFCCC Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa, explain how working together will help unlock faster emission cuts.

Authored by Hein Schumacher and Patricia Espinosa

Next week in New York, leaders from around the world will gather to attend the United Nations General Assembly. Each leader will need to address critical issues facing their nation, climate change being a shared challenge they all must face up to.

We recognise the profound responsibility we bear in addressing the escalating climate crisis in our respective fields. We also recognise that individual action is essential but insufficient, which is why we are issuing a call to action for both business and government.

Governments must create strong 1.5°C-aligned Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that strive for the highest level of ambition and provide a policy framework that supports business decarbonisation opportunities by providing adequate support for private investment.

NDCs should include:

- Ambitious goals in GHG emissions reduction and commitments

- Commitments to conserve and restore forests

- Targets, measures and reward schemes to support the transition to and maintenance of regenerative agriculture practices

- Strategies to accelerate the transition to the use of renewable and recycled feedstocks for chemicals

CEOs should, at the same time, back these efforts with verifiable 1.5°C-aligned climate transition and investment plans.

The economic case for climate action

Since Nicholas Stern’s landmark review of the economics of climate change, it has been clear that the costs of not acting to tackle climate change are much higher than the costs of taking action. [a]

This is because, as climate change intensifies, it will disrupt every aspect of every industry, impacting business performance, employment, quality of life and the overall socio-economic stability of nations.

Another path is possible. The Paris Agreement could unlock $23 trillion worth of global investment opportunity in emerging markets. [b] And, if we deliver on limiting global warming to 1.5°C, the global economic costs of climate change will reduce by around two-thirds. [c]

Public and private sector investment in climate action is needed

Unilever understands the opportunity and the imperative, investing €150 million in decarbonisation of manufacturing over the next three years, as well as €1 billion in climate, nature and circular economy projects by 2030.

But no one business on its own can drive change at the scale needed. Combating climate breakdown demands a united front across business and government.

Calling for government and business action

That’s why, ahead of UN General Assembly week, we’re joining forces to emphasise the critical need for heightened national climate ambition – and action – to keep the world to a 1.5°C-aligned pathway, and the importance for business leaders to actively support these efforts.

Government leaders must take bold decisions, knowing that their actions over the next few months will shape the next few years for better or for worse. The first step is for ambitious NDCs to be agreed. The second step is for governments to implement them and create supportive legal, policy and regulatory frameworks that will catalyse business to decarbonise their operations.

Business can support government ambition by sending demand signals that they want more ambitious national targets and that they intend to play their part in delivering them – from setting science-based targets across value chains to investing in decarbonising efforts and to using their influence for good.

Which is why we call on every business that values the future of our planet, as well as their own commercial success, to seize the opportunity in the coming months to advocate for stronger and more ambitious NDCs and align their plans with them.

The time for half-measures is over

In this divided and fractured world, inertia, complacency and cognitive dissonance are leading us towards avoidable catastrophes. Yet we know that, with the right combination of ambition and implementation, a more prosperous future is within reach.

Policymakers and businesses must recognise the jeopardy we face and calibrate every decision they take with this in mind. The world is watching, and the decisions made this year will shape the trajectory of our planet for present and future generations.

For more information, read Unilever’s briefing (PDF 439.07 KB) with input from the team at Onepoint5, which sets out what effective NDCs look like and how businesses can support them.

Read Nicholas Stern’s review of the economics of climate change (PDF 1MB)

Climate Investment Opportunities in Emerging Markets (PDF 7.60 MB)

Climate damage projections beyond annual temperature | Nature Climate Change

- Green Banking

- General Sustainability

Unilever: Leading the way through ESG collaboration

17 December 2021

- More like this Less like this

As the third-largest consumer products company in the world in terms of revenue, Unilever operates roughly 400 global and local brands, including 13 billion Euro brands such as Dove, Lux, Axe, Rexona, Knorr, and Lipton. They’ve used their standing in the marketplace to become a force for good in environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG), actively working towards a green agenda for the last decade. Today the company takes steps to support the UN Sustainable Development Goals, which includes improving the health and well-being of people worldwide and working toward net-zero emissions in the making and use of their products by 2039. Unilever is also dedicated to enhancing millions of people's livelihoods with fairness in the workplace and inclusive business practices, most recently announcing further equality and inclusion measures to support more SMEs in its extended value chain, including minority-owned suppliers.

Treasury supporting a green agenda

According to Tuomas Raesaenen, Treasury Manager for Unilever, the company’s commitment to ESG trickles down to every area of the organization – including Treasury. “The goal is to operate in such a way that everything we do as an organization is consistent with our corporate purpose,” says Tuomas. “From a finance perspective, finding ways we can align with the corporate sustainability goals can be a challenge.”

They began by funding green initiatives, issuing their first green bond in 2014. However, Unilever also wanted to do something sustainable with their cash– and that’s really where they found a lack of opportunity. “We were looking for a vehicle that would help us hit our targets of safety and yield but at the same time support green investments and give us access to liquidity if we needed it.” So Unilever turned to their banking partners, including HSBC, and challenged them to find or create a solution that would meet their needs.

Many green deposits are concentrated in developed markets,” says Tuomas. “The fact that HSBC has included emerging markets is very helpful for us, considering our broad geographical footprint. Tuomas Raesaenen | Treasury Manager for Unilever

Marking a world of firsts together

With a long relationship history, HSBC has a good understanding of Unilever’s needs. “The bank was very supportive of our goals, and being in many of the markets we operate in was critical,” says Tuomas. “The team really did their homework and delivered a solution that was pretty polished from the start, not just some ideas of what they might be able to do." This allowed Unilever to work with HSBC to further refine the solution, which had to ensure full transparency. "The reporting was critical. We needed an audit trail to evidence that the cash was going to fund green priorities and that the deposits were 100% sustainable.”

The result was a series of firsts in the industry. HSBC developed the first EUR 31-Day Notice Account green deposit in the UK to accommodate Negative Credit Interest (NCI) – and Unilever became the first UK headquartered global corporate to make an initial deposit. HSBC also brought to market an INR green deposit in India, as well as VND and USD green deposit in Vietnam, in which Unilever placed the initial investment. This made the bank the first to achieve a global approach to green deposits by using their extensive network to go green in the UK, India, and Vietnam simultaneously. “Many green deposits are concentrated in developed markets,” says Tuomas. “The fact that HSBC has included emerging markets is very helpful for us, considering our broad geographical footprint.”

Beyond the cash deposit solutions, Unilever was also the first to agree to work with HSBC to trial a digital and automated self-service experience. This gave them the ability to transfer deposits themselves for multiple geographies, including emerging markets, using their existing channels.

Collaboration leads to a better solution

“One of the reasons we challenged our banking partners was not only to meet our own sustainability goals,” says Tuomas. "But really to carve a path to help others see how Treasury can support corporate sustainability safely and profitably." The collaboration between Unilever and HSBC, he says, is an example on how to develop solutions that create a competitive yield whilst delivering positive impact towards our ESG ambition. "Together, we are investing in the future."

According to Gordon Elliot, Regional Sector Head, Global Liquidity and Cash Management, HSBC, the time is precisely right. “A reaction to the COVID pandemic we didn’t expect is that the green agenda seems to have grown in importance,” he says. “As we did a series of webinars in 2020 around working capital, Brexit and COVID-19 – green initiatives and ESG kept coming up. The pandemic seems to have brought focus on what we can all do to protect the health and well-being of the entire planet.” Tuomas agrees that these issues are increasingly top of mind for corporates. “More and more, clients want to do business with companies who are focused on sustainability.”

That's why it's crucial for banks and corporations to work together, says Michelle Arundale, Director, Sales, Global Liquidity and Cash Management, HSBC. "When we team up with clients, we can make a real difference," Michelle says. "Unilever is that kind of client, working with us over the years to develop several scalable new products, including our green deposit offerings, that others in the marketplace can now take advantage of."

Transition Pathways

Unilever case study: Managing ESG controversy within a sustainable portfolio

Castlefield’s Ita McMahon explains how the team actively engaged with Unilever over its continued presence in Russia

Ita McMahon, partner, Castlefield Investment Partners

As anyone who works in sustainable investing will tell you, it’s an awful feeling when you scroll through the morning news and find a negative ESG headline about a stock held in one of your firm’s funds.

It’s even worse when that company is Unilever – a titan in responsible business and widely held in sustainable portfolios – and the controversy is the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing conflict there. Unilever has been in the spotlight in recent months for its continued presence in Russia, even though many, many other Western brands have now exited.

See also: – Castlefield Q&A: Having an influence as a smaller investor

So how does the investment manager respond when controversy arises at a company held in a sustainable portfolio? Unilever and its operations in Russia, the aggressor in the war in Ukraine, provides a live example of how we address such controversies.

The motivation for writing about this is to highlight the careful judgment calls we make in these circumstances but also to point out that no company is perfect. Sustainable fund managers can be guilty of portraying companies as either “good” (we will invest) or “bad” (we won’t). Of course, there are egregious industries that many sustainable funds avoid, ourselves included. Nevertheless, we need to move beyond a simplistic framing of the corporate sector and be more open about the fact that bad things can and do happen at good companies. It’s how the company responds that counts.

Like most sustainable fund managers, there’s a process that kicks in when any of our holdings get in the press for the wrong reasons. First, we seek to establish the facts. We’ll then conduct an informed engagement with the company, before we finally form our view on the issue.

And so to Unilever

Let’s start by acknowledging the contribution that Unilever has made over the past two decades to corporate responsibility. An early adopter of sustainability reporting and ambitious goal-setting, it has continued to build a strong track record ever since. Although not without marketing mis-steps and isolated incidents of poor practice, Unilever’s consistent commitment to responsible sourcing, human rights and reducing its environmental impacts have set the standard for the consumer goods sector for years. It’s worth recognising too the readiness of the investor relations team to talk openly and thoughtfully about the situation in Russia.

The company employs 3,000 people in the country and prior to the invasion, it accounted for around 2% of Unilever’s global revenue. From the outset, Unilever denounced Russian aggression in Ukraine. It continued to operate there, and to produce a broad range of products, but took steps to isolate the subsidiary by stopping imports to and exports from Russia, as well as stemming all capital flows. Importantly, Unilever is operating under UK sanctions law and therefore has no contact with its Russian business.

Unilever’s view is that continuing operations within strict parameters is the “least worst” option, and preferable to closing the business and risking state appropriation. It has also been unsuccessful in finding a buyer that would both safeguard staff and “avoid the Russian state potentially gaining further benefit.” In effect, it is stuck with the status quo. Crucially for us, all profits generated within Russia are ring-fenced, so thoughtful and principled UK investors can take comfort that they are not benefitting from the arrangement. That said, the subsidiary will be paying tax to the Russian state.

Active engagement

As part of our engagement, we requested an update on Russia in the Q3 results call scheduled for October. We made our position on the matter clear: Unilever’s Russian operations are adding very little to the investment case from a financial or reputational perspective; in fact the opposite is true. We would like to see Unilever exit the market, notwithstanding the difficulties in finding a suitable buyer and its reluctance to sever ties with local employees. It’s easy to be cynical about statements around employee wellbeing, but, as the company itself notes, Unilever colleagues in other volatile locations will be watching on with interest. Plus, as an employee-owned business ourselves, we want other firms to value each and every employee.

However, the risk of a forced exit is growing; Danone and Carlsberg have had operations appropriated by the Russian state in the past few months. Unilever is increasingly an outlier, at a time when many other Western brands have now left Russia . There are no signs of any major consumer boycotts at the moment, but that could change with an effective NGO campaign.

Can Unilever still be considered a sustainable leader and a titan in responsible business? The company’s hard-earned reputation for sustainability has been damaged, but remains propped up, for now at least, by the comprehensiveness of its sustainability programme to date.

We remain invested, taking reassurance that Russian profits are ringfenced away from the rest of the business. We’ll continue to engage on this topic and to push for further updates from management, particularly as the new CEO has now settled in. This is a classic example of a “bad” thing happening at an otherwise largely “good” company, highlighting both the complexities of multinational firms and the judgment calls that we make as sustainable investors.

MORE ARTICLES ON

Latest Stories

Sustainable seas: The role investors can play in marine conservation

Investing in sustainable ocean-based initiatives can help protect one of our planet’s most vital resources, writes Amy Clarke

Q&A: Women are coming up with the solutions that are needed to solve the climate crisis

Heading for Change’s Sana Kapadia answers PA Future’s questions on gender-smart climate investing

Road to COP29: Presidency announces ‘Action Agenda’, Loss and Damage fund updates

Finance the ‘centrepiece’ of Action Agenda initiatives ahead of COP29

Over 440 companies reporting on TNFD as it passes first anniversary

The next cohort of TNFD adopters will be announced at COP16 in Cali, Colombia in October 2024

Takeaways from New York Climate Week 2024 (so far)

‘It’s time for a reality check,’ as Global To-Do list revealed

SBTN pilot ‘proves companies have a clear and credible path to take action for nature’

The organisation has published the outcomes of its pilot, with target setting ‘helping to raise corporate ambition’

Unilever Global Change location

Our ambition is to deliver net zero emissions across our value chain

A business imperative.

Climate change is a significant threat to people and our planet. It is also a material risk to our business. We’ve set more ambitious climate targets and identified clearer actions to respond to this challenge.

There are no quick fixes, especially given the nature of our business and value chain. But we firmly believe more urgent action can strengthen Unilever.

Regenerative farming can make our supply chain more resilient by protecting crops against extreme weather. Using renewable energy and recovering waste heat in our operations can help to make us more efficient and less exposed to volatile energy markets. And reformulating our products and moving to better packaging can offer consumers more sustainable products.

Reducing emissions

Our ambition is to reach net zero across our value chain by 2039, and our focus is on reducing our emissions by 2030 in line with what science says is needed.

With around 98% of our value chain emissions occurring outside our own operations, influencing our supply partners, and leading by example, are critical.

We’ve strengthened our value chain targets to raise our ambition and distinguish between industrial emissions, and those linked to land and agriculture – reflecting the need for different approaches. We continue to focus on absolute emissions reductions in the areas we can influence most.

Delivering on our ambitious targets is our priority.

We have three near-term targets:

Our operations

Reduce absolute operational GHG emissions (Scope 1 & 2) by 100% by 2030 from a 2015 baseline

Our value chain – energy and industrial

Reduce absolute Scope 3 energy and industrial GHG emissions [a] by 42% by 2030 from a 2021 baseline

Our value chain – forest, land and agriculture

Reduce absolute Scope 3 forest, land and agriculture (FLAG) GHG emissions [b] by 30.3% by 2030 from a 2021 baseline

Learn about our updated Climate Transition Action Plan

Driving widescale change

Our updated Climate Transition Action Plan (CTAP) focuses on ten action areas where we can best drive positive impact by 2030. Some of these are:

- Growing our Supplier Climate Programme to help key suppliers become climate leaders

- Investing in deforestation-free supply chains

- Reformulating products to use lower-emissions ingredients without compromising performance

Alongside actions like these, we’re pushing hard for system-level change. Change that will address barriers to faster emissions reduction, in each of our ten action areas and overall.

The climate challenge is huge. And we’re facing it head-on.

More about our sustainability work

Select a page to find out more.

Our Climate Transition Action Plan

Our Climate Transition Action Plan, updated in 2024, sets out our actions to lower our emissions by 2030.

Using our voice for a zero carbon future

We’re calling on everyone - businesses, governments and international alliances - to come together to tackle climate change.

Deforestation-free supply chain

We’re working to ensure a deforestation-free supply chain as part of our efforts to protect nature, tackle climate change and promote human rights.

Unilever Climate & Nature Fund

We have a goal to invest €1 billion in climate, nature, and waste reduction projects.

Putting the chemicals industry on a pathway to net zero

We’re working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from chemicals by collaborating with suppliers, reformulating some of our products, and pushing for the chemicals industry to transform.

Unilever Annual Report

Read more about our Growth Action Plan and how we are stepping up our execution to deliver improved performance.

Our commitment to responsible business

Find out more about our progress and reporting on issues such as human rights, equity, diversity and inclusion, and safety.

Our other sustainability topics

The world – and our business – needs resilient natural and agricultural ecosystems to thrive. We’re committed to contributing to the protection and regeneration of nature, within and beyond our value chain.

We’ve been working hard to create a circular economy for plastic packaging for a number of years. We’ve learnt that transformation takes time. Given the size of this challenge, we’re using our innovation capabilities to find new, scalable solutions.

Livelihoods

The impacts of inequality go far beyond income – to health, human rights and economic growth. So we’re working to improve the livelihoods of people in our global value chain.

Energy and industrial emissions from purchased goods and services (associated with ingredients, packaging), upstream transport and distribution, energy and fuel-related activities, direct emissions from use of sold products (associated with HFC propellants), end-of-life treatment of sold products, and downstream leased assets (associated with ice cream retail cabinets).

FLAG emissions from purchased goods and services (associated with ingredients).

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG. Why is the consumer goods group backpedalling on responsible-business targets? Explore the issues with this 'instant ...

The ESG (Economic, Social and Governance) Value Driver Framework was developed by the Principles of Responsible Investment Management and the UN Global Compact to help companies communicate how sustainability- related actions link with business benefits. Following are examples from Unilever's Sustainable Living Plan Reports for 2012-2014.

ESG Profile Unilever Plc S&P Global Ratings |Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Evaluation This product is not a credit ratingJuly 9, 2021 5. Governance Profile 80. /100. Sector/Region Score (28/35) Unilever is headquartered in the U.K., a country we view as having high governance standards.

Our measurements show Unilever's progress with packaging materials. In 2022, 55% of its packaging was recyclable or compostable, up 5% since 2019. Reducing plastic use has clear environmental benefits and hasn't come at a cost to Unilever's bottom line. Sales grew 15% from 2019 to 2022. We believe that as consumers become more conscious ...

Executive management sustainability oversight. The ULE is responsible for driving our strategy and the Growth Action Plan, working in tandem with our Board to promote the success of the business.Sustainabilty is performance managed by the ULE in the same way as other aspects of the Growth Action Plan, using 'Objectives and Key Results' (OKRs) which are reviewed every quarter, alongside a ...

The challenge and opportunity. We have been driving an ambitious sustainability agenda for over two decades. Yet, in the face of ever-growing economic, environmental and social challenges, we are evolving our approach. Ringing the alarm and setting long-term ambitions isn't good enough anymore. Now is the time to focus on delivering impact by ...

This set of case studies explores aspects of how Unilever's sustainability activities align with increased investor interest in environmental, social and governance (ESG) topics. Specifically, it looks at how Unilever: • Integrates sustainability into its strategy • Adopts a commercial tone in communicating with investors

London/Rotterdam - Unilever today celebrated 10 years of the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, which is now in its tenth and final year. Alan Jope, CEO, reinforced Unilever's commitment to making sustainable living commonplace for 8 billion people, and called for collective action to ensure that the crises of social inequality and climate are not neglected in the wake of Covid-19.

Summary. British multinational Unilever is one of the largest fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies globally, with more than 400 brands across 190 countries, and about 148,000 employees. Headquartered in London, Unilever is a leader in all its product categories, most recently organized into five business groups: Beauty and Wellbeing (€ ...

ESG & Sustainable Finance ... Case Study. Unilever. ... The Unilever Sustainable Living Plan is Unilever's groundbreaking and ambitious roadmap to achieve its growth vision in a way that increases the social value of its brands while simultaneously reducing its environmental impact. Unilever will report its progress to achieving the goals set ...

Paul Polman was the CEO of Unilever from 2009 to 2019 and helped develop the UN Global Goals. He is a coauthor of Net Positive . Andrew Winston is one of the world's leading thinkers on ...

For example, Unilever's Sustainable Living Plan (USLP), initiated by Paul Polman (Unilever's former CEO) in November 2010, was a holistic plan aimed at achieving three critical outcomes by 2020 ...

ArticlePDF Available. Chapter 2 Unilever's Drive for Sustainability and CSR - Changing the Game. June 2011. DOI: 10.1108/S2045-0605 (2011)0000001007. Authors: Philip H. Mirvis. Babson College.

The economic case for climate action. ... For more information, read Unilever's briefing (PDF 439.07 KB) with input from the team at Onepoint5, which sets out what effective NDCs look like and how businesses can support them. [a] Read Nicholas Stern's review of the economics of climate change (PDF 1MB) [b]

According to Tuomas Raesaenen, Treasury Manager for Unilever, the company's commitment to ESG trickles down to every area of the organization - including Treasury. "The goal is to operate in such a way that everything we do as an organization is consistent with our corporate purpose," says Tuomas. "From a finance perspective, finding ...

Our Annual Report and Accounts (PDF 14.76 MB) includes sustainability disclosures aligned to our strategy.. An overview of all sustainability performance measures reported in the 2023 Annual Report and Accounts that were subject to external assurance in the reporting period can be found in Unilever's Basis of Preparation 2023 (PDF 751.67 KB) - including definitions, scope and data ...

Unilever case study: Managing ESG controversy within a sustainable portfolio. As anyone who works in sustainable investing will tell you, it's an awful feeling when you scroll through the morning news and find a negative ESG headline about a stock held in one of your firm's funds. It's even worse when that company is Unilever - a titan ...

Tackling manufacturing waste. We've spent more than a decade reducing waste and recycling in our operations. We're still striving to do better and find innovative ways to keep resources in use for longer. Find out about the actions we're taking to be a responsible business, our additional sustainability disclosures and our sustainability ...