- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : June 12

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Philippine independence declared

During the Spanish-American War , Filipino rebels led by Emilio Aguinaldo proclaim the independence of the Philippines after 300 years of Spanish rule. By mid-August, Filipino rebels and U.S. troops had ousted the Spanish, but Aguinaldo’s hopes for independence were dashed when the United States formally annexed the Philippines as part of its peace treaty with Spain.

The Philippines, a large island archipelago situated off Southeast Asia, was colonized by the Spanish in the latter part of the 16th century. Opposition to Spanish rule began among Filipino priests, who resented Spanish domination of the Roman Catholic churches in the islands. In the late 19th century, Filipino intellectuals and the middle class began calling for independence. In 1892, the Katipunan, a secret revolutionary society, was formed in Manila, the Philippine capital on the island of Luzon. Membership grew dramatically, and in August 1896 the Spanish uncovered the Katipunan’s plans for rebellion, forcing premature action from the rebels. Revolts broke out across Luzon, and in March 1897, 28-year-old Emilio Aguinaldo became leader of the rebellion.

By late 1897, the revolutionaries had been driven into the hills southeast of Manila, and Aguinaldo negotiated an agreement with the Spanish. In exchange for financial compensation and a promise of reform in the Philippines, Aguinaldo and his generals would accept exile in Hong Kong. The rebel leaders departed, and the Philippine Revolution temporarily was at an end.

In April 1898, the Spanish-American War broke out over Spain’s brutal suppression of a rebellion in Cuba. The first in a series of decisive U.S. victories occurred on May 1, 1898, when the U.S. Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey annihilated the Spanish Pacific fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay in the Philippines. From his exile, Aguinaldo made arrangements with U.S. authorities to return to the Philippines and assist the United States in the war against Spain. He landed on May 19, rallied his revolutionaries, and began liberating towns south of Manila. On June 12, he proclaimed Philippine independence and established a provincial government, of which he subsequently became head.

His rebels, meanwhile, had encircled the Spanish in Manila and, with the support of Dewey’s squadron in Manila Bay, would surely have conquered the Spanish. Dewey, however, was waiting for U.S. ground troops, which began landing in July and took over the Filipino positions surrounding Manila. On August 8, the Spanish commander informed the United States that he would surrender the city under two conditions: The United States was to make the advance into the capital look like a battle, and under no conditions were the Filipino rebels to be allowed into the city. On August 13, the mock Battle of Manila was staged, and the Americans kept their promise to keep the Filipinos out after the city passed into their hands.

While the Americans occupied Manila and planned peace negotiations with Spain, Aguinaldo convened a revolutionary assembly, the Malolos, in September. They drew up a democratic constitution, the first ever in Asia, and a government was formed with Aguinaldo as president in January 1899. On February 4, what became known as the Philippine Insurrection began when Filipino rebels and U.S. troops skirmished inside American lines in Manila. Two days later, the U.S. Senate voted by one vote to ratify the Treaty of Paris with Spain. The Philippines were now a U.S. territory, acquired in exchange for $20 million in compensation to the Spanish.

In response, Aguinaldo formally launched a new revolt–this time against the United States. The rebels, consistently defeated in the open field, turned to guerrilla warfare, and the U.S. Congress authorized the deployment of 60,000 troops to subdue them. By the end of 1899, there were 65,000 U.S. troops in the Philippines, but the war dragged on. Many anti-imperialists in the United States, such as Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan , opposed U.S. annexation of the Philippines, but in November 1900 Republican incumbent William McKinley was reelected, and the war continued.

On March 23, 1901, in a daring operation, U.S. General Frederick Funston and a group of officers, pretending to be prisoners, surprised Aguinaldo in his stronghold in the Luzon village of Palanan and captured the rebel leader. Aguinaldo took an oath of allegiance to the United States and called for an end to the rebellion, but many of his followers fought on. During the next year, U.S. forces gradually pacified the Philippines. In an infamous episode, U.S. forces on the island of Samar retaliated against the massacre of a U.S. garrison by killing all men on the island above the age of 10. Many women and young children were also butchered. General Jacob Smith, who directed the atrocities, was court-martialed and forced to retire for turning Samar, in his words, into a “howling wilderness.”

In 1902, an American civil government took over administration of the Philippines, and the three-year Philippine insurrection was declared to be at an end. Scattered resistance, however, persisted for several years.

More than 4,000 Americans perished suppressing the Philippines–more than 10 times the number killed in the Spanish-American War. More than 20,000 Filipino insurgents were killed, and an unknown number of civilians perished.

In 1935, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was established with U.S. approval, and Manuel Quezon was elected the country’s first president. On July 4, 1946, full independence was granted to the Republic of the Philippines by the United States.

Also on This Day in History June | 12

Under pressure, Little League Baseball allows girls to play

One million people demonstrate in new york city against nuclear weapons, terrorist gunman attacks pulse nightclub in orlando, florida.

This Day in History Video: What Happened on June 12

Civil rights leader medgar evers is assassinated, indira gandhi convicted of election fraud.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

D‑Day landing forces converge

Big red sets record at belmont stakes, george herbert walker bush is born, anne frank receives a diary, nicole brown simpson and ron goldman murdered.

President Reagan challenges Gorbachev to "Tear down this wall"

The Story of June 12, 1898: The Philippine Declaration of Independence

June 12, 1898 is one of the most significant dates in philippine history..

June 12, 1898 is one of the most significant dates in Philippine history. On this day, General Emilio Aguinaldo formally proclaimed the independence of the Philippines from Spain after over 300 years of colonial rule.

The declaration took place in Aguinaldo’s ancestral home in Kawit, Cavite , with the Philippine flag being raised and the national anthem being played for the first time.

While the Kawit declaration did not receive immediate international recognition, it was a pivotal moment that asserted Filipino nationhood and sovereignty.

It came amidst a complex geopolitical situation, with the Philippine Revolution against Spain, the Spanish-American War , and the emerging American colonial era in the Philippines. The story behind the June 12, 1898 declaration provides insights into the Filipino struggle for self-determination.

Background: The Philippine Revolution

The roots of the June 12 declaration can be traced to the Philippine Revolution against Spanish colonial rule, which began in August 1896. Secret revolutionary societies like the Katipunan , founded by Andres Bonifacio , initiated an armed struggle for independence.

Emilio Aguinaldo , then the mayor of Kawit, Cavite, emerged as a leader of the revolution in Cavite.

After initial successes, Aguinaldo and other leaders accepted exile to Hong Kong in December 1897 with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato , which involved the Spanish paying the revolutionaries in exchange for a truce. However, they purchased weapons in Hong Kong to continue the fight .

The Spanish-American War and Aguinaldo’s Return

The situation changed dramatically with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in April 1898. The United States, which had been monitoring the Cuban and Philippine revolutions against Spain, declared war after the USS Maine incident in Havana.

On May 1, 1898, the U.S. Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey decisively defeated the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay . Aguinaldo, who had been communicating with U.S. officials, saw an opportunity to advance Philippine independence .

With Dewey’s help, Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines aboard the USS McCulloch on May 19. American forces provided his troops with weapons seized from the Spanish. Aguinaldo rallied his revolutionary forces and began liberating towns in Cavite .

The Declaration of Independence on June 12

On June 12, 1898 , a month after his return, Aguinaldo gathered revolutionary leaders and local representatives in his home in Kawit. There, between 4 and 5 p.m., he formally proclaimed the independence of the Philippines from Spain .

The event, attended by a huge crowd, involved the first public display of the Philippine flag sewn in Hong Kong by Marcela Agoncillo and her daughters. The Marcha Nacional Filipina , composed by Julian Felipe as the national anthem, was played by the San Francisco de Malabon band .

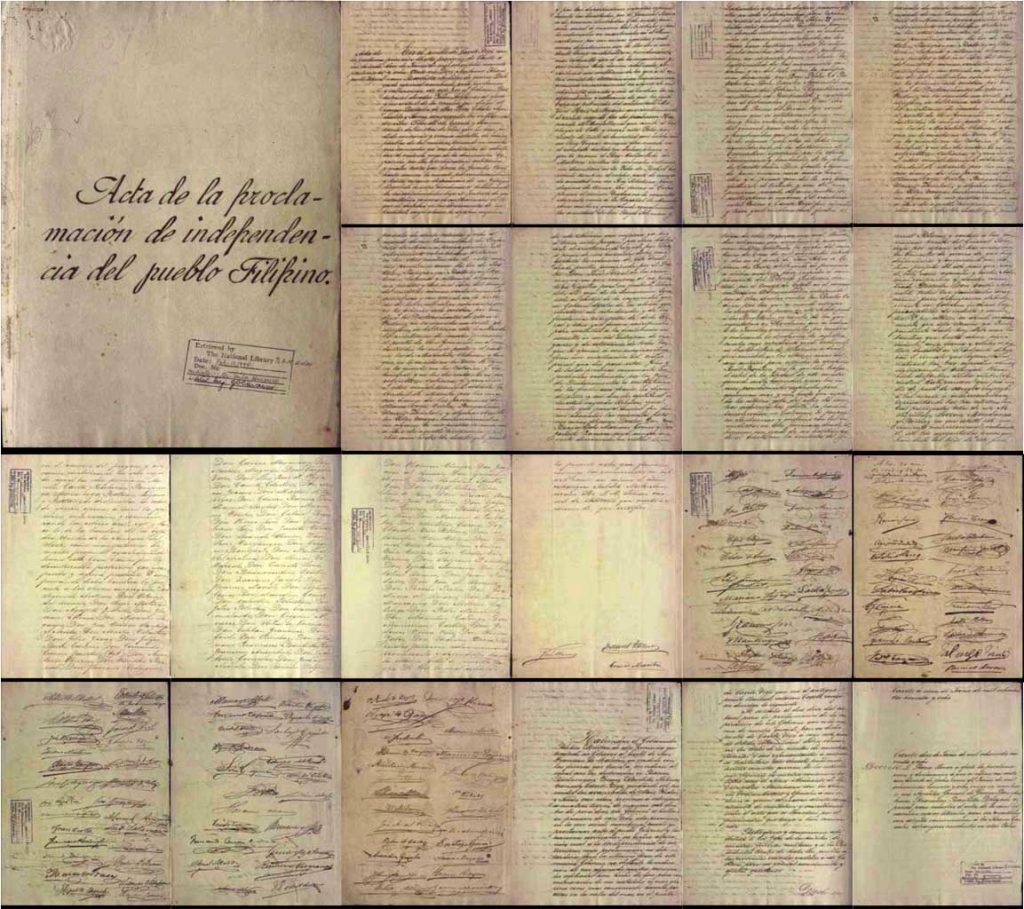

Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista prepared the Spanish text of the Act of the Declaration of Independence and read it at the gathering. The declaration was signed by 98 Filipinos appointed by Aguinaldo, as well as one American artillery officer, Colonel L.M. Johnson , who attended as a witness .

The declaration included a list of grievances against Spanish rule stretching back to Magellan’s arrival in 1521. It conferred on Aguinaldo the powers to lead the revolutionary government, including granting pardons and amnesty. The wording echoed parts of the U.S. Declaration of Independence .

Diplomatic Complexities and the Malolos Congress

Aguinaldo had hoped that the U.S. would recognize Philippine independence, similar to its stance towards Cuba .

However, American officials took no action that would suggest recognition of the declaration . The true intentions of the U.S. towards the Philippines remained unclear at this stage.

The declaration took place amidst a complex diplomatic situation, with other colonial powers like Germany, Britain, France and Japan having warships in Manila Bay to monitor the situation . Germany in particular showed interest in acquiring the Philippines if the U.S. did not .

On August 1, the June 12 proclamation was ratified by 190 municipal presidents from 16 provinces in Bacoor, Cavite . In September 1898, the Malolos Congress modified the declaration upon the urging of Apolinario Mabini, removing language that essentially placed the Philippines under American protection .

The Treaty of Paris and the Philippine-American War

The Spanish-American War ended with the Treaty of Paris signed on December 10, 1898. In the treaty, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States for $20 million, along with Guam and Puerto Rico .

The treaty was not recognized by Aguinaldo’s government, which had not been represented in the negotiations. On January 23, 1899, the First Philippine Republic was formally established with the promulgation of the Malolos Constitution and Aguinaldo as president .

Tensions rose as it became clear that the U.S. would not recognize Philippine independence. On February 4, 1899, the Philippine-American War broke out and lasted until 1902. The U.S. prevailed against the Filipinos, and established the Insular Government to administer the islands as an American colony .

The Long Road to Internationally-Recognized Independence

The dream of June 12 remained unfulfilled for decades under U.S. colonial rule. The U.S. set up political institutions and prepared the Philippines for eventual self-rule, but full independence was slow in coming.

The Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934 provided for the independence of the Philippines by 1946, after a 10-year transition period. World War II and the Japanese occupation from 1942-1945 intervened during this period.Finally, on July 4, 1946 , the United States granted independence to the Philippines.

The date was chosen by the U.S. to coincide with its own Independence Day. For many years, Filipinos celebrated July 4 as their Independence Day .

June 12 as the National Day of Independence

A strong tradition of celebrating June 12 as the true Independence Day persisted among Filipino historians and nationalists. In 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal issued Presidential Proclamation No. 28 which declared June 12 as Flag Day, emphasizing its importance .

On August 4, 1964, upon the advice of historians and the urging of nationalists, Macapagal signed Republic Act No. 4166 into law, designating June 12 as the country’s Independence Day . The law also renamed July 4 as Philippine Republic Day .

Since 1964, June 12 has been celebrated annually as the National Day of the Philippines, with ceremonies and programs across the country.

The day is a regular holiday , and government offices and schools are closed. The main commemoration usually takes place at Aguinaldo’s house in Kawit, which is now a national shrine .

The story of the June 12, 1898 Declaration of Independence in Kawit is central to the narrative of the Filipino people’s struggle for freedom and nationhood. While it did not immediately result in internationally recognized independence, it was a bold assertion of sovereignty against colonial rule.

The path from Kawit to true independence was long and arduous, with the Philippines experiencing American colonial rule and occupation by Japan before achieving full self-determination in 1946. The choice of June 12 as Independence Day in 1964 represents a recognition of the primacy of the Filipino revolutionary struggle.

Today, the declaration in Kawit is remembered as a defining moment in Philippine history, one that continues to inspire national pride and a striving for self-determination.

The complex events surrounding the declaration also provide a window into the geopolitical realities of the time, and the challenges faced by an emerging nation in asserting its place in the world.

Written by Louie Sison

My name is Louie and welcome to HyperLocal PH. Launched in February 2024, this website is dedicated to bringing you the most captivating and comprehensive stories about Filipino lifestyle, history, news, travel, and food. Join us in this journey!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Ensuring the longevity and reliability of equipment hinges on the critical process of balancing rotors. But where did this technology originate, and how has it developed over time?

Originally, rotor balancing was done manually. Craftsmen would attach weights to the rotor and check for evenness by eye. With the advent of technology, the first electronic devices were developed, allowing for more precise vibration measurements and accurate placement of balancing weights. Modern devices, such as the Balanset-1A, have revolutionized the field, providing high measurement accuracy and automatic balancing calculations.

Employing modern balancing instruments like the Balanset-4 guarantees measurement reliability and accuracy, extending equipment lifespan and reducing repair costs. Equipped with microprocessors and laser sensors, these devices are essential in contemporary industrial settings.

To improve the reliability and efficiency of your equipment, consider investing in modern balancing instruments. These tools help reduce component wear and prevent costly breakdowns.

Here you can read more about [url=https://vibromera.eu/] Field balancing equipment for industrial maintenance and repair [/url]

balancing stands

Balancing Stands: The Unsung Heroes of Rotor Quality Welcome to the wonderful world of balancing stands, where the art of rotor balancing meets the science of engineering and a sprinkle of humor! If you’ve ever wondered how to keep those pesky vibrating rotors at bay, then you’ve hit the jackpot with these balancing stands.

First things first, let’s unravel the mystery of these balancing stands. Imagine a flat plate, elegantly mounted on a set of cylindrical springs, kind of like a dancer on tiptoes. This dance floor is where all the action happens! These stands are designed to ensure that your rotors – whether they are from crushers, fans, or vacuum pumps – are balanced to perfection.

The Anatomy of Balancing Stands Now, let’s break down what makes these balancing stands so extraordinary. Picture this: you’ve got a sturdy plate resting on four impressive cylindrical springs. Easy to assemble? You bet! But that’s not all. You’ll find an electric motor strutting its stuff on this plate, acting as a spindle. It’s like a mini roller coaster ride for your rotors – hold on tight!

Ever heard of an impulse sensor? Nope, it’s not a new dance move! This little gem tracks the motor rotor’s rotation angle. Thanks to this wise gadget, the balancing stand can pinpoint where to apply corrective mass, ensuring your rotor is spinning smoothly rather than performing its version of the Macarena.

From Abrasive Wheels to Vacuum Pumps: Versatility Galore! But wait, there’s more! Let’s talk about the different types of balancing stands available. If you’re balancing an abrasive wheel, you’re in for a treat. The configuration remains the same – our beloved plate and springs combo, but this time with an added twist. Need to balance a vacuum pump that spins faster than your last marathon? No problem! These stands can handle that too, with speeds reaching up to 60,000 RPM. Yep, you read that right. It’s like trying to balance a cheetah on a trampoline!

And speaking of synchronizing things, the stands don’t just bounce around aimlessly. They come equipped with vibration sensors that measure vibrations in different sections. You can think of it as having a team of super-humans analyzing every little wiggle and jive – all while you sit back and sip your coffee. Talk about multitasking!

Quality Assurance Like Never Before Now, you may be wondering, do these balancing stands actually work? Well, let’s put it this way: these stands can achieve a residual unbalance that could make even the most experienced engineers shed a tear of joy. With a mere 0.01 mm/sec vibration at speeds of 8000 rpm, you’re looking at a balancing performance so precise, it could win a beauty pageant!

@Fantastic isn’t it? And for fans? You better believe it! On the right stand, the residual vibration can go below 0.8 mm/s, which is like hitting the gym and dropping your weights by half. Clients have reported that the designs work tremendously, yielding a tidy residual vibration of just 0.1 mm/s in the manufacturing of duct fans.

Who Needs Balancing Stands? Let’s get real: if you’re running any kind of rotor machinery, you need balancing stands in your life. Whether you’re a part of a fan factory or you just like tinkering with your family’s lawn mower, these stands are your new best friends. They will save you from unwanted vibrations and ensure that you’re not only working hard but hardly working – if you catch my drift.

And the best part? You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to use them. With a few simple instructions and the right tools, you can construct your own balancing stands. So if you’re ever feeling bored or just want to impress your friends with your DIY skills, just whip out those balancing stands and watch everyone’s jaws drop!

The Final Spin In conclusion, balancing stands are nothing short of magical. They take the guesswork out of rotor balancing and tie everything together in a neat little bow. With their simple yet effective design, they are perfect for a variety of applications. Whether you’re a professional engineer or a weekend warrior who enjoys home projects, you’re now equipped with the knowledge on how to elevate your balancing game!

So the next time you hear any vibrations, just give a little nod to the balancing stands; they’re the unsung heroes working tirelessly behind the scenes. Remember, life is too short for unbalanced rotors, so embrace the joy of balancing stands and keep everything spinning smoothly!

Interested in discovering more about these fabulous balancing stands? Look no further! Just click around our products or give us a shout. We promise, it’ll be a balancing act you won’t want to miss!

The Sign of the Eruption of Mount Pinatubo on June 12, 1991

Inside Out 2 Premieres in Philippine Cinemas to Record-Breaking Box Office Numbers

HyperLocal PH All Rights Reserved. Powered by Xage Digital

Add to Collection

Public collection title

Private collection title

No Collections

Here you'll find all collections you've created before.

- Classifieds

- Philippines

- June 10, 2016 , 04:25pm

The Proclamation of Philippine Independence

Gregorio del Pilar and his troops in 1898. Source: Arnold Dumindin via philippineamericanwar.webs.com

Declaration of Independence

With a government in operation, Aguinaldo thought that it was necessary to declare the independence of the Philippines. He believed that such a move would inspire the people to fight more eagerly against the Spaniards and at the same time, lead the foreign countries to recognize the independence of the country. Mabini, who had by now been made Aguinaldo’s unofficial adviser, objected. He based his objection on the fact that it was more important to reorganize the government in such a manner as to convince the foreign powers of the competence and stability of the new government than to proclaim Philippine independence at such an early period. Aguinaldo, however, stood his ground and won.

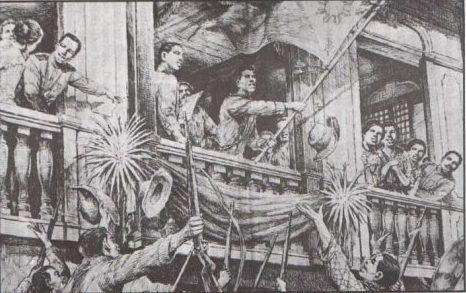

On June 12, between four and five in the afternoon, Aguinaldo, in the presence of a huge crowd, proclaimed the independence of the Philippines at Cavite el Viejo (Kawit). For the first time, the Philippine National Flag, made in Hongkong by Mrs. Marcela Agoncillo, assisted by Lorenza Agoncillo and Delfina Herboza, was officially hoisted and the Philippine National March played in public. The Act of the Declaration of Independence was prepared by Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista, who also read it. A passage in the Declaration reminds one of another passage in the American Declaration of Independence. The Philippine Declaration was signed by ninety-eight persons, among them an American army officer who witnessed the proclamation. The proclamation of Philippine independence was, however, promulgated on August 1 when many towns have already been organized under the rules laid down by the Dictatorial Government. (Source: History of the Filipino People. Teodoro A. Agoncillo)

Proclamation of Philippine Independence

The most significant achievement of Aguinaldo’s Dictatorial Government was the proclamation of Philippine Independence in Kawit, Cavite, on June 12, 1898. The day was declared a national holiday. Thousands of people from the provinces gathered in Kawit to witness the historic event. The ceremony was solemnly held at the balcony of General Emilio Aguinaldo’s residence. The military and civil officials of the government were in attendance. A dramatic feature of the ceremony was the formal unfurling of the Filipino flag amidst the cheers of the people. At the same time, the Philippine National Anthem was played by the band. Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista solemnly read the “Act of the Declaration of Independence” which he himself wrote. The declaration was signed by 98 persons. One of the signers was an American, L.M. Johnson, Colonel of Artillery. The Philippines: A Unique Nation. Dr. Sonia M. Zaide

Comments (0)

Click here to cancel reply

- An Uncomplicated Mind

- At Ground Level

- Environment

- Opinion & Analysis

- Printed Front Page

- Simple Promotion

"The mission of the US-Philippines Society is to build on the rich and longstanding historical ties between the United States of America and the Philippines. …and to bring that unique relationship to the 21st century."

Weekly Issues | Reflections on June 12, 1898: Philippine Declaration of Independence amid a “Dangerous International Environment”

June 8, 2020

Featured Contributor

Dr. Frank Jenista

U.S. Foreign Service Officer

Question 1: From the perspective of a historian, what are some lesser known aspects of the Philippines’ Declaration of Independence on June 12, 1898?

Filipinos know a great deal about that momentous day. General Aguinaldo had recently returned from exile in Hong Kong to restart the revolution against Spain. There was great enthusiasm upon his return, and even more celebration on June 12 when, in his home town of Kawit, Cavite, the new national flag was displayed, the new national anthem was played and the Filipinos became the first Asian colony to declare their independence.

What few Filipinos and Americans today know about is the dangerous international environment of the time or the Filipinos’ diplomatic strategy – of which the Declaration of Independence was one part.

Question 2: What do you mean by “the dangerous international environment?”

This was the height of the “Age of Imperialism.” Major world powers took pride in building colonial empires. By 1898 much of Asia was under the control of the British, the French and, most recently, the Japanese.

Shortly after Admiral Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet in May 1898, German, British, French and Japanese warships showed up in Manila Bay, looking for possible opportunities to extend their empires.

The Philippines – the Pearl of the Orient – was a most attractive target. What might happen if the Spanish were driven out? Could some or all of those rich islands become available? There were many intriguing possibilities – and many interested parties.

Germany, now united and seeking to enhance its position on the world stage, was particularly interested – and aggressive. A strong German fleet had been sent to Asia to seek opportunities. In Manila Bay Admiral Von Diederichs landed German Marines on Bataan and opened direct communication with the Spanish in Manila, in violation of then-current rules of neutrality. When ordered to cease and desist by Dewey, Von Diederichs refused, setting up a possible conflict between German and US fleets in Manila Bay. Fighting was averted when the British commander intervened, placing his ships between the Germans and the Americans. Von Diederichs may have been willing to risk conflict between Germany and the upstart USA, but he could not be the cause of a war with the UK.

Von Diederichs also sent one of his warships to Cebu to try to negotiate a separate treaty between Germany and Filipino leaders in the central Visayan islands. Both Germany and Britain had earlier made treaties with the Sultan of Sulu, in the Muslim south of the archipelago.

Question 3: What was the Filipino revolutionary leaders’ response to these dangers?

The Filipinos were following international events closely and their strategy was – Cuba. The situation in Cuba paralleled that in the Philippines – rebels seeking freedom from oppressive Spanish overlords. By the late 1890s it was clear that Americans had great sympathy for the Cuban rebels and seemed likely to assist them in throwing out the Spanish and recognizing Cuban independence – with the all-important guarantee of protection against outside forces. Could the Filipinos manage a similar outcome?

Their first official approach to the Americans came in January, 1897, while the Katipunan revolt was still in progress, 11 months before the Pact of Biac-na-Bato and Aguinaldo’s exile in December of 1897. Filipino leaders in Hong Kong (Jose M. Basa, Doroteo Cortes and A.G. Medina) sent a letter to the US Consul General in Hong Kong imploring the US “to extend its protection over the Filipinos who are now suffering under the tyranny of Spain.”

Cuba was prominent in their petition, praying “that help be extended to the Filipinos to expel the Spanish by force, just as the Emperor Napoleon [sic Louis XVI] helped America in the war of separation from England, by whose aid the Americans attained independence, like assistance to be given to the Cubans who are now fighting for independence – which protection and support the Filipinos now hope and pray may be granted to them, because they are in precisely the same position as the Cubans with their land drenched in blood.”

In November of 1897 the US Consul in Hong Kong reported a discussion with Felipe Agoncillo, a representative “of the new republic of the Philippines,” requesting American assistance against Spain, especially the transport of arms and for a treaty with the US.

After Aguinaldo and other exiled rebel leaders arrived in Hong Kong, and as war rumors increased in the United States, communications picked up significantly among Aguinaldo, American consuls in Hong Kong and Singapore – and Dewey himself once the American fleet arrived in Hong Kong.

The Cuba strategy was at the center of all these conversations. Consul Pratt in Singapore reported that Aguinaldo “declared his ability to establish a proper and responsible government on liberal principles and would be willing to accept the same terms for the country as the United States intend giving to Cuba.”

Aguinaldo kept pressing for an American commitment to the Cuban model for the Filipinos, an assurance which neither the consuls nor Dewey were in a position to give because the McKinley administration had no Philippine policy yet, beyond “defeat the Spanish.”

Dewey personally was supportive, declaring that he knew both Cubans and Filipinos and that, in his opinion, the Filipinos were more capable of self-government. Dewey’s support was amply demonstrated. Two of Aguinaldo’s associates, Jose Alejandrino and Andres de Garchitorena, sailed with Dewey when his fleet left to fight the Spanish in Manila Bay. Aguinaldo was then brought back to the Philippines aboard the USS McCulloch , was welcomed personally by Dewey and spent his first night as Dewey’s guest aboard the flagship Olympia.

The Americans transported some 2,000 Remington rifles and 200,000 rounds of ammunition from Hong Kong to Manila for Aguinaldo’s rebel forces, and turned over all weapons seized from surrendering Spanish forces in Cavite and Corregidor, as well as 8 Spanish steam launches – the first vessels of a new Philippine navy.

Dewey encouraged Aguinaldo to display the Filipino flag on these launches and saluted the Filipinos according to proper naval etiquette, drawing protests from the German and British commanders. When asked why he permitted the Filipinos to use a flag unrecognized by their vessels, Dewey answered that the Filipinos used the flag with his knowledge and consent; and moreover, “that by their courage and firmness in the war against the Spaniards they were worthy of using that right.”

Aguinaldo used one of these launches to travel to Subic to attack the Spanish there, only to be confronted and threatened in Subic Bay by the German cruiser Irene on behalf of the Spaniards – yet another display of German aggressiveness. Aguinaldo had no choice but to return to Manila and report to Dewey, who sent two US cruisers to Subic to order the Irene out and to assist in forcing the surrender of the Spanish garrison.

It is in the context of this Filipino diplomatic strategy that the June 12 Declaration of Independence appears. Seeking official American recognition of the Declaration, General Aguinaldo reported that “I sent a committee to the Admiral to apprise him of it, inviting him at the same time to take part in the ceremonies, which took place with due formality.” Dewey asked that his absence be excused, and neither he nor any of his officers attended. (It should be noted that by June 12 American officials had been instructed to take no action which could be interpreted as a statement of future American policy – which by then was under intense deliberation in Washington.)

Question 4: But wasn’t there an American present at the celebrations on June 12?

There was – a mysterious Colonel L. M. Johnson. It was important to Aguinaldo that some American should be there whom the assembled people would consider a representative of the United States. Colonel Johnson, in US Army uniform, signed the Declaration of Independence and was presented as Aguinaldo’s chief of artillery, but his name does not appear thereafter in any of Aguinaldo’s extensive papers, nor in US Army records.

Question 5: Filipinos have criticized Aguinaldo for praising the United States in the Declaration of Independence. Your thoughts?

It is important to recall the context. Aguinaldo’s primary goal, once he had gained American support for the fight against Spain, was to achieve international – but especially American – recognition of Philippine independence and, equally essential given the dangerous environment, American protection against interference by outside powers. Aguinaldo repeatedly made similar statements in speeches and in his writings, in the hope that Americans could be persuaded to treat the Philippines like Cuba.

Question 6: Why the difference? Why didn’t the US offer the Philippines what it gave Cuba?

As noted earlier, at the outbreak of war McKinley had no policy toward the Philippines – and had a well-deserved reputation for indecision. Even after peace talks with Spain began in Paris, he changed his instructions to the American negotiators at least four times. His opening position was just a long-term treaty for use of Subic Bay as a naval base – in the same way he asked the Cubans for Guantanamo Bay. The Filipino representatives quickly agreed, and in addition asked for a treaty with the US similar to the one that the Cubans were getting – meaning protection from the imperial powers lurking around their embryonic Philippine republic.

In the end, McKinley decided that the United States could not be responsible for defending the Philippines against all other nations unless he controlled the Philippines. It was one thing to promise to protect Cubans on one island 90 miles from American shores, but quite another to be responsible for defending 7,000 islands 7,000 miles away.

The Filipinos – up to this point allied with the United States against Spain – refused to give up their struggle for independence against the Spanish only to end up under a different colonizer. The inevitable and regrettable result was the Filipino-American War.

As we look back, the truly unfortunate aspect of this history is that the Filipinos, despite a successful revolt against the Spanish, and despite declaring their independence on June 12, 1898, were doomed to lose their independence to the geopolitical forces at play during this high age of imperialism. A newly-independent Philippines would have been too weak, too rich – and too tempting. The Pearl of the Orient was going to be a victim – again.

Question 7: Who do you think might have taken the Philippines if the Americans had sailed away after defeating Spain?

My guess is Britain. It was the strongest imperial power in Asia and strategically could not allow anyone – but especially its main European rival Germany – to cut off lines of communication between British colonies in Malaya/Singapore/Hong Kong and Australia/New Zealand.

No historical evidence has surfaced yet, but it is plausible that Britain approached the dithering McKinley and said, in effect, “if you don’t, we will, so the Germans can’t.”

Question 8: If the Philippines was likely to be a victim of imperial powers, were features of American colonialism different?

First, let me be perfectly clear that I do not defend colonialism. As a scholar, however, it is important to distinguish among the various forms of colonialism. American colonialism was unique. I call it imperialism with a guilty conscience.

Many prominent Americans opposed taking the Philippines as a colony, seeing it as a betrayal of America’s own history of revolution against a colonial ruler. The Treaty of Paris, for example, was hotly debated and approved by a margin of just one vote.

From the beginning the US publicly proclaimed that it intended to prepare the Philippines for independence – a policy Queen Victoria denounced as utter nonsense for a colonial power. Even before the war was over American teachers arrived to create a free public education system. Local and provincial elections were held in 1904, in 1906 elections were held for the lower house of congress (the Philippine Assembly) and by 1916 both houses of congress were Filipino.

In other words, less than 20 years after June 12, 1898 the great majority of Philippine domestic policy was being decided by elected Filipinos and carried out by Filipino administrators.

Would that have satisfied those assembled in Kawit to celebrate the Declaration of Independence? No. Would the rapid transition to Filipino hands have happened under any other colonial power? Also No.

About the Author

Dr. Frank Jenista grew up in the Philippines as the son of missionary parents and earned his Ph.D. in Philippine History from the University of Michigan. During his 25-year career as a US diplomat, Dr. Jenista twice served “back home” at the US Embassy in Manila.

Comments welcome – [email protected] or [email protected]

Weekly Issues: An Update on U.S. Humanitarian Assistance in the BARMM

Weekly issues | a guide to the visiting forces agreement: understanding the past and adapting to the future, related posts, philippine national day message.

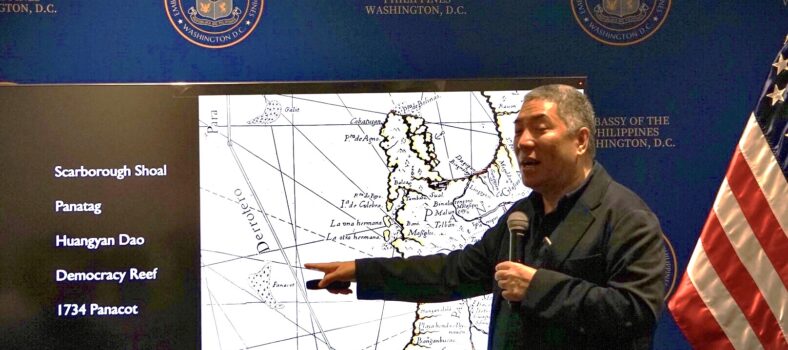

Understanding Philippine History through Maps and Visual Arts

Sept 7 | Rizal, Maps, and the Emergence of the Filipino Nation

1898: philippine declaration of independence, geopolitical currents, and american expansionism, privacy overview.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

WEEK 7: 1898 Declaration of Philippine Independence, The Malolos Constitution and First Philippine Republic LEARNING CONTENT

Related papers

This section consists of lesson materials for students related to the Philippines and its role in American History. This information about Philippine independence and how it links the Philippines and the United States is intended for students in middle school, chiefly eighth grade, and are aligned with the North Carolina Standard Course of Study. This project helps to fill gaps in American History and its connection to the Philippines. Additionally, adding depth and cultural awareness to existing American History curriculum provides a clearer, more balanced, and deeper understanding of history topics and how our nation’s past and present are intertwined with other nations. This section is part of The Philippines in American History, which includes teacher guides, found at https://www.academia.edu/87754439/The_Philippines_in_American_History Section published November 2022

In this essay, I talk about the "history" of changing the day of Philippine independence from 04 July to 12 June. I discussed how postcolonial anti-Americanism, Macapagal's crabbiness towards Washington, and the Philippine Historical Association had interwoven involvement in such a historical event in our recognition of freedom and independence every 12 June. I cited some interesting points from Joseph Scalice, Leloy Claudio, and Rey Ileto. I wrote this essay as a reflection last 12 June after witnessing online the ceremonial flag-raising and wreath-laying at Luneta Park, led for the first time by President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., and the less celebrated Republic Day every 04 July.

The essence of celebrating our country’s independence from political control cannot be reflected in parades, fairs, or even speeches. Gaining liberty necessitates for a continuous struggle of taking heed the lessons of the past. We will be free if we surpass the common problem of poverty. We will be free if we hurdle the usual political exploitation that we experience from abusive elements in society. We will be free if we are empowered to stand by our rights. We will be free if we know how to respect the rights of our fellowmen. And we will be free if we are able to change and reform our government for the better.

In his sociopolitical essay "The Philippines a Century Hence," Dr. Jose Rizal talked about the Filipino people's suffering during the Spanish colonization and how the Philippines would become in the next century.

The Revolution of 1896 marks the birth of the Filipino nation. It was a time when propagandistas and radical advocates, both in and outside the Catholic Church, were pressing for an independent nation, separate from Spain. It was an extraordinary time, and this volume makes available to readers selected works by scholars from different pats f the world, using varied historical sources, bringing in new perspectives on the war. Topics in this volume include the influx of refugees to Cavite, which affected the rivalry between Bonifacio and Aguinaldo; the travails of the Franciscan friars; the hopes and fears of a young Spanish soldier; the restrained exasperation of an aide-de-camp to the German cruiser squadron; and the circuitous "intra-Asia" trade. These and other essays in this volume reassess questions on the Revolution and the period it covers - gender, ethnicity, the military and corruption. A prologue where, besides introducing the topics and authors that write in the book, I explore the discourses of difference during the late Spanish period. Since those were the times of Social Darwinism and the Great Chain of Being, as well as the peak of influence of science, implying innate differences among "races", the role of Spain is specially ankward. While considered as "inferior" by Europeans, Spaniards did efforts to widen the gap in the colonies between them and the colonized as a way to solve their lack of legitimacy. It was one of the reasons of the Philippine Revolution in 1896 and their ultimate exit from the Philippine at 1898.

Revista Juris Poiesis, 2016

Journal of Medical Sciences

Hombres y mujeres de Espíritu en el siglo XXI, 2012

Coral Reefs and Associated Marine Fauna around the Arabian Peninsula, 2024

Selçuk Üniversitesi Türkiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi

Journal of Education Faculty, 2006

Pakar Pendidikan, 2024

ChemInform, 2010

New Educational Review, 2020

Dünya İnsan Bilimleri Dergisi, 2019

Vjesnik Istarskog arhiva, 2019

npj Genomic Medicine, 2021

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

ESSAY OF "Proclamation of the Philippines Independence": There is a quote that "a great nation is a nation that is able to appreciate the services of its heroes". On the 12th, June is the day the Philippines became independent.

Philippine independence declared. During the Spanish-American War, Filipino rebels led by Emilio Aguinaldo proclaim the independence of the Philippines after 300 years of Spanish rule. By mid...

June 12, 1898 is one of the most significant dates in Philippine history. On this day, General Emilio Aguinaldo formally proclaimed the independence of the Philippines from Spain after over 300 years of colonial rule.

The most significant achievement of Aguinaldo’s Dictatorial Government was the proclamation of Philippine Independence in Kawit, Cavite, on June 12, 1898. The day was declared a national holiday. Thousands of …

In this document, the Filipino people announced to the world their right to be free and independent and their determination to defend their freedom with their lives, fortunes, and honor.

The Philippine Declaration of Independence (Filipino: Pagpapahayag ng Kasarinlan ng Pilipinas; Spanish: Declaración de Independencia de Filipinas) [a] was proclaimed by Filipino revolutionary forces general Emilio Aguinaldo on …

From the beginning the US publicly proclaimed that it intended to prepare the Philippines for independence – a policy Queen Victoria denounced as utter nonsense for a colonial power. Even before the war was over …

The Filipino revolutionary forces under Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed the sovereignty and independence of the Philippine islands from Spanish colonization in Kawit, Cavite on June 12, 1898. Then on January 23, 1899, the …

The official declaration of the Philippines’ independence is one of the most treasured milestones that we Filipinos achieved in our rich history. After being colonized by many nations in the ...