Understanding Gender, Sex, and Gender Identity

It's more important than ever to use this terminology correctly..

Posted February 27, 2021 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

- The Fundamentals of Sex

- Find a sex therapist near me

Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene hung a sign outside her Capitol office door that said “There are TWO genders: MALE & FEMALE. ‘Trust the Science!’” There are many reasons to question hanging such a sign, but given that Rep. Taylor Greene invoked science in making her assertion, I thought it might be helpful to clarify by citing some actual science. Put simply, from a scientific standpoint, Rep. Taylor Greene’s statement is patently wrong. It perpetuates a common error by conflating gender with sex . Allow me to explain how psychologists scientifically operationalize these terms.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA, 2012), sex is rooted in biology. A person’s sex is determined using observable biological criteria such as sex chromosomes, gonads, internal reproductive organs, and external genitalia (APA, 2012). Most people are classified as being either biologically male or female, although the term intersex is reserved for those with atypical combinations of biological features (APA, 2012).

Gender is related to but distinctly different from sex; it is rooted in culture, not biology. The APA (2012) defines gender as “the attitudes, feelings, and behaviors that a given culture associates with a person’s biological sex” (p. 11). Gender conformity occurs when people abide by culturally-derived gender roles (APA, 2012). Resisting gender roles (i.e., gender nonconformity ) can have significant social consequences—pro and con, depending on circumstances.

Gender identity refers to how one understands and experiences one’s own gender. It involves a person’s psychological sense of being male, female, or neither (APA, 2012). Those who identify as transgender feel that their gender identity doesn’t match their biological sex or the gender they were assigned at birth; in some cases they don’t feel they fit into into either the male or female gender categories (APA, 2012; Moleiro & Pinto, 2015). How people live out their gender identities in everyday life (in terms of how they dress, behave, and express themselves) constitutes their gender expression (APA, 2012; Drescher, 2014).

“Male” and “female” are the most common gender identities in Western culture; they form a dualistic way of thinking about gender that often informs the identity options that people feel are available to them (Prentice & Carranza, 2002). Anyone, regardless of biological sex, can closely adhere to culturally-constructed notions of “maleness” or “femaleness” by dressing, talking, and taking interest in activities stereotypically associated with traditional male or female gender identities. However, many people think “outside the box” when it comes to gender, constructing identities for themselves that move beyond the male-female binary. For examples, explore lists of famous “gender benders” from Oxygen , Vogue , More , and The Cut (not to mention Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head , whose evolving gender identities made headlines this week).

Whether society approves of these identities or not, the science on whether there are more than two genders is clear; there are as many possible gender identities as there are people psychologically forming identities. Rep. Taylor Greene’s insistence that there are just two genders merely reflects Western culture’s longstanding tradition of only recognizing “male” and “female” gender identities as “normal.” However, if we are to “trust the science” (as Rep. Taylor Greene’s recommends), then the first thing we need to do is stop mixing up biological sex and gender identity. The former may be constrained by biology, but the latter is only constrained by our imaginations.

American Psychological Association. (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist , 67 (1), 10-42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024659

Drescher, J. (2014). Treatment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. In R. E. Hales, S. C. Yudofsky, & L. W. Roberts (Eds.), The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychiatry (6th ed., pp. 1293-1318). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Moleiro, C., & Pinto, N. (2015). Sexual orientation and gender identity: Review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems. Frontiers in Psychology , 6 .

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women should be, shouldn't be, are allowed to be, and don't have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 26 (4), 269-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Jonathan D. Raskin, Ph.D. , is a professor of psychology and counselor education at the State University of New York at New Paltz.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 6. Influencing and Conforming

6.3 Person, Gender, and Cultural Differences in Conformity

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the social psychological literature concerning differences in conformity between men and women.

- Review research concerning the relationship between culture and conformity.

- Explain the concept of psychological reactance and describe how and when it might occur.

Although we have focused to this point on the situational determinants of conformity, such as the number of people in the majority and their unanimity, we have not yet considered the question of which people are likely to conform and which people are not. In this section, we will consider how personality variables, gender, and culture influence conformity.

Person Differences

Even in cases in which the pressure to conform is strong and a large percentage of individuals do conform (such as in Solomon Asch’s line-judging research), not everyone does so. There are usually some people willing and able to go against the prevailing norm. In Asch’s study, for instance, despite the strong situational pressures, 24% of the participants never conformed on any of the trials.

People prefer to have an “optimal” balance between being similar to, and different from, others (Brewer, 2003). When people are made to feel too similar to others, they tend to express their individuality, but when they are made to feel too different from others, they attempt to increase their acceptance by others. Supporting this idea, research has found that people who have lower self-esteem are more likely to conform in comparison with those who have higher self-esteem. This makes sense because self-esteem rises when we know we are being accepted by others, and people with lower self-esteem have a greater need to belong. And people who are dependent on and who have a strong need for approval from others are also more conforming (Bornstein, 1992).

Age also matters, with individuals who are either younger or older being more easily influenced than individuals who are in their 40s and 50s (Visser & Krosnick, 1998). People who highly identify with the group that is creating the conformity are also more likely to conform to group norms, in comparison to people who don’t really care very much (Jetten, Spears, & Manstead, 1997; Terry & Hogg, 1996).

However, although there are some differences among people in terms of their tendency to conform (it has even been suggested that some people have a “need for uniqueness” that leads them to be particularly likely to resist conformity; Snyder & Fromkin, 1977), research has generally found that the impact of person variables on conformity is smaller than the influence of situational variables, such as the number and unanimity of the majority.

Gender Differences

Several reviews and meta-analyses of the existing research on conformity and leadership in men and women have now been conducted, and so it is possible to draw some strong conclusions in this regard. In terms of conformity, the overall conclusion from these studies is that that there are only small differences between men and women in the amount of conformity they exhibit, and these differences are influenced as much by the social situation in which the conformity occurs as by gender differences themselves.

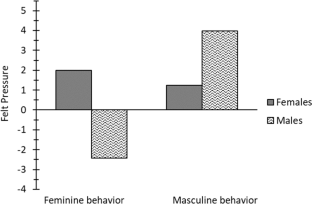

On average, men and women have different levels of self-concern and other-concern. Men are, on average, more concerned about appearing to have high status and may be able to demonstrate this status by acting independently from the opinions of others. On the other hand, and again although there are substantial individual differences among them, women are, on average, more concerned with connecting to others and maintaining group harmony. Taken together, this means that, at least when they are being observed by others, men are likely to hold their ground, act independently, and refuse to conform, whereas women are more likely to conform to the opinions of others in order to prevent social disagreement. These differences are less apparent when the conformity occurs in private (Eagly, 1978, 1983).

The observed gender differences in conformity have social explanations—namely that women are socialized to be more caring about the desires of others—but there are also evolutionary explanations. Men may be more likely to resist conformity to demonstrate to women that they are good mates. Griskevicius, Goldstein, Mortensen, Cialdini, and Kenrick (2006) found that men, but not women, who had been primed with thoughts about romantic and sexual attraction were less likely to conform to the opinions of others on a subsequent task than were men who had not been primed to think about romantic attraction.

In addition to the public versus private nature of the situation, the topic being discussed also is important, with both men and women being less likely to conform on topics that they know a lot about, in comparison with topics on which they feel less knowledgeable (Eagly & Chravala, 1986). When the topic is sports, women tend to conform to men, whereas the opposite is true when the topic is fashion. Thus it appears that the small observed differences between men and women in conformity are due, at least in part, to informational influence.

Because men have higher status in most societies, they are more likely to be perceived as effective leaders (Eagly, Makhijani, & Klonsky, 1992; Rojahn & Willemsen, 1994; Shackelford, Wood, & Worchel, 1996). And men are more likely to be leaders in most cultures. For instance, women hold only about 20% of the key elected and appointed political positions in the world (World Economic Forum, 2013). There are also more men than women in leadership roles, particularly in high-level administrative positions, in many different types of businesses and other organizations. Women are not promoted to positions of leadership as fast as men are in real working groups, even when actual performance is taken into consideration (Geis, Boston, & Hoffman, 1985; Heilman, Block, & Martell, 1995).

Men are also more likely than women to emerge and act as leaders in small groups, even when other personality characteristics are accounted for (Bartol & Martin, 1986; Megargee, 1969; Porter, Geis, Cooper, & Newman, 1985). In one experiment, Nyquist and Spence (1986) had pairs of same- and mixed-sex students interact. In each pair there was one highly dominant and one low dominant individual, as assessed by previous personality measures. They found that in pairs in which there was one man and one woman, the dominant man became the leader 90% of the time, but the dominant woman became the leader only 35% of the time.

Keep in mind, however, that the fact that men are perceived as effective leaders, and are more likely to become leaders, does not necessarily mean that they are actually better, more effective leaders than women. Indeed, a meta-analysis studying the effectiveness of male and female leaders did not find that there were any gender differences overall (Eagly, Karau, & Makhijani, 1995) and even found that women excelled over men in some domains. Furthermore, the differences that were found tended to occur primarily when a group was first forming but dissipated over time as the group members got to know one another individually.

One difficulty for women as they attempt to lead is that traditional leadership behaviors, such as showing independence and exerting power over others, conflict with the expected social roles for women. The norms for what constitutes success in corporate life are usually defined in masculine terms, including assertiveness or aggressiveness, self-promotion, and perhaps even macho behavior. It is difficult for women to gain power because to do so they must conform to these masculine norms, and often this goes against their personal beliefs about appropriate behavior (Rudman & Glick, 1999). And when women do take on male models of expressing power, it may backfire on them because they end up being disliked because they are acting nonstereotypically for their gender. A recent experimental study with MBA students simulated the initial public offering (IPO) of a company whose chief executive was either male or female (personal qualifications and company financial statements were held constant across both conditions). The results indicated a clear gender bias as female chief executive officers were perceived as being less capable and having a poorer strategic position than their male counterparts. Furthermore, IPOs led by female executives were perceived as less attractive investments (Bigelow, Lundmark, McLean Parks, & Wuebker, 2012). Little wonder then that women hold fewer than 5% of Fortune 500 chief executive positions.

One way that women can react to this “double-bind” in which they must take on masculine characteristics to succeed, but if they do they are not liked, is to adopt more feminine leadership styles, in which they use more interpersonally oriented behaviors such as agreeing with others, acting in a friendly manner, and encouraging subordinates to participate in the decision-making process (Eagly & Johnson, 1990; Eagly et al., 1992; Wood, 1987). In short, women are more likely to take on a transformational leadership style than are men—doing so allows them to be effective leaders while not acting in an excessively masculine way (Eagly & Carli, 2007; Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt, & van Egen, 2003).

In sum, women may conform somewhat more than men, although these differences are small and limited to situations in which the responses are made publicly. In terms of leadership effectiveness, there is no evidence that men, overall, make better leaders than do women. However, men do better as leaders on tasks that are “masculine” in the sense that they require the ability to direct and control people. On the other hand, women do better on tasks that are more “feminine” in the sense that they involve creating harmonious relationships among the group members.

Cultural Differences

In addition to gender differences, there is also evidence that conformity is greater in some cultures than others. Your knowledge about the cultural differences between individualistic and collectivistic cultures might lead you to think that collectivists will be more conforming than individualists, and there is some support for this. Bond and Smith (1996) analyzed results of 133 studies that had used Asch’s line-judging task in 17 different countries. They then categorized each of the countries in terms of the degree to which it could be considered collectivist versus individualist in orientation. They found a significant relationship: conformity was greater in more collectivistic than in individualistic countries.

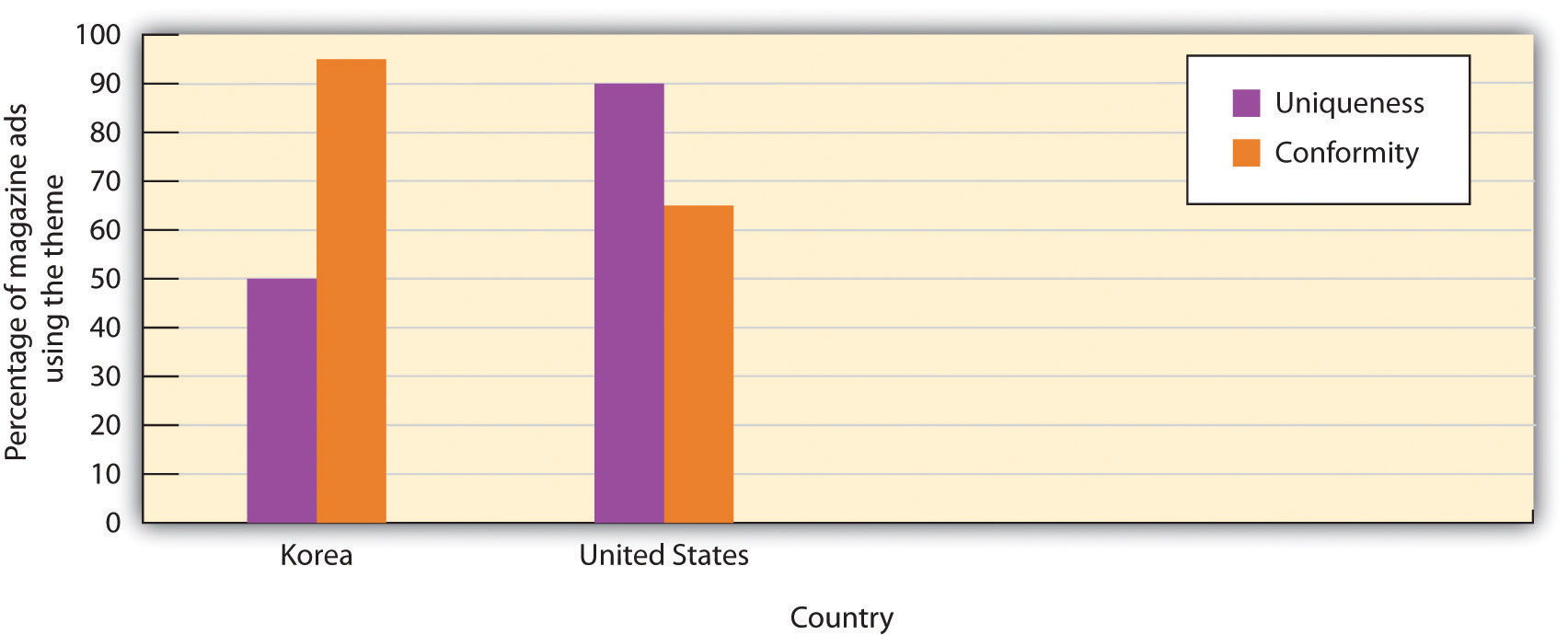

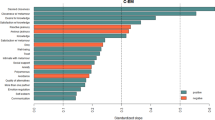

Kim and Markus (1999) analyzed advertisements from popular magazines in the United States and in Korea to see if they differentially emphasized conformity and uniqueness. As you can see in Figure 6.14, “Culture and Conformity,” they found that while U.S. magazine ads tended to focus on uniqueness (e.g., “Choose your own view!”; “Individualize”) Korean ads tended to focus more on themes of conformity (e.g., “Seven out of 10 people use this product”; “Our company is working toward building a harmonious society”).

Kim and Markus (1999) found that U.S. magazine ads tended to focus on uniqueness whereas Korean ads tended to focus more on conformity.

In summary, although the effects of individual differences on conformity tend to be smaller than those of the social context, they do matter. And gender and cultural differences can also be important. Conformity, like most other social psychological processes, represents an interaction between the situation and the person.

Psychological Reactance

Conformity is usually quite adaptive overall, both for the individuals who conform and for the group as a whole. Conforming to the opinions of others can help us enhance and protect ourselves by providing us with important and accurate information and can help us better relate to others. Following the directives of effective leaders can help a group attain goals that would not be possible without them. And if only half of the people in your neighborhood thought it was appropriate to stop on red and go on green but the other half thought the opposite—and behaved accordingly—there would be problems indeed.

But social influence does not always produce the intended result. If we feel that we have the choice to conform or not conform, we may well choose to do so in order to be accepted or to obtain valid knowledge. On the other hand, if we perceive that others are trying to force or manipulate our behavior, the influence pressure may backfire, resulting in the opposite of what the influencer intends.

Consider an experiment conducted by Pennebaker and Sanders (1976), who attempted to get people to stop writing graffiti on the walls of campus restrooms. In some restrooms they posted a sign that read “Do not write on these walls under any circumstances!” whereas in other restrooms they placed a sign that simply said “Please don’t write on these walls.” Two weeks later, the researchers returned to the restrooms to see if the signs had made a difference. They found that there was much less graffiti in the second restroom than in the first one. It seems as if people who were given strong pressures to not engage in the behavior were more likely to react against those directives than were people who were given a weaker message.

When individuals feel that their freedom is being threatened by influence attempts and yet they also have the ability to resist that persuasion, they may experience psychological reactance , a strong motivational state that resists social influence (Brehm, 1966; Miron & Brehm, 2006). Reactance is aroused when our ability to choose which behaviors to engage in is eliminated or threatened with elimination. The outcome of the experience of reactance is that people may not conform or obey at all and may even move their opinions or behaviors away from the desires of the influencer.

Reactance represents a desire to restore freedom that is being threatened. A child who feels that his or her parents are forcing him to eat his asparagus may react quite vehemently with a strong refusal to touch the plate. And an adult who feels that she is being pressured by a car sales representative might feel the same way and leave the showroom entirely, resulting in the opposite of the sales rep’s intended outcome.

Of course, parents are sometimes aware of this potential, and even use “reverse psychology”—for example, telling a child that he or she cannot go outside when they really want the child to do so, hoping that reactance will occur. In the musical The Fantasticks , neighboring fathers set up to make the daughter of one of them and the son of the other fall in love with each other by building a fence between their properties. The fence is seen by the children as an infringement on their freedom to see each other, and as predicted by the idea of reactance, they ultimately fall in love.

In addition to helping us understand the affective determinants of conformity and of failure to conform, reactance has been observed to have its ironic effects in a number of real-world contexts. For instance, Wolf and Montgomery (1977) found that when judges give jury members instructions indicating that they absolutely must not pay any attention to particular information that had been presented in a courtroom trial (because it had been ruled as inadmissible), the jurors were more likely to use that information in their judgments. And Bushman and Stack (1996) found that warning labels on violent films (for instance, “This film contains extreme violence—viewer discretion advised”) created more reactance (and thus led participants to be more interested in viewing the film) than did similar labels that simply provided information (“This film contains extreme violence”). In another relevant study, Kray, Reb, Galinsky, and Thompson (2004) found that when women were told that they were poor negotiators and would be unable to succeed on a negotiation task, this information led them to work even harder and to be more successful at the task.

Finally, within clinical therapy, it has been argued that people sometimes are less likely to try to reduce the harmful behaviors that they engage in, such as smoking or drug abuse, when the people they care about try too hard to press them to do so (Shoham, Trost, & Rohrbaugh, 2004). One patient was recorded as having reported that his wife kept telling him that he should quit drinking, saying, “If you loved me enough, you’d give up the booze.” However, he also reported that when she gave up on him and said instead, “I don’t care what you do anymore,” he then enrolled in a treatment program (Shoham et al., 2004, p. 177).

Key Takeaways

- Although some person variables predict conformity, overall situational variables are more important.

- There are some small gender differences in conformity. In public situations, men are somewhat more likely to hold their ground, act independently, and refuse to conform, whereas women are more likely to conform to the opinions of others in order to prevent social disagreement. These differences are less apparent when the conformity occurs in private.

- Conformity to social norms is more likely in Eastern, collectivistic cultures than in Western, independent cultures.

- Psychological reactance occurs when people feel that their ability to choose which behaviors to engage in is eliminated or threatened with elimination. The outcome of the experience of reactance is that people may not conform or obey at all and may even move their opinions or behaviors away from the desires of the influencer.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Bill laughed at the movie, even though he didn’t think it was all that funny; he realized he was laughing just because all his friends were laughing.

- Frank realized that he was starting to like jazz music, in part because his roommate liked it.

- Jennifer went to the mall with her friends so that they could help her choose a gown for the upcoming prom.

- Sally tried a cigarette at a party because all her friends urged her to.

- Phil spent over $150 on a pair of sneakers, even though he couldn’t really afford them, because his best friend had a pair.

Bartol, K. M., & Martin, D. C. (1986). Women and men in task groups. In R. D. Ashmore & F. K. Del Boca (Eds.), The social psychology of female-male relations . New York, NY: Academic Press.

Bigelow, L. S., Lundmark, L., McLean Parks, J. M., & Wuebker, R. (2012). Skirting the issues? Experimental evidence of gender bias in IPO prospectus evaluations. Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1556449

Bond, R., & Smith, P. B. (1996). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119 (1), 111–137.

Bornstein, R. F. (1992). The dependent personality: Developmental, social, and clinical perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 112 , 3–23.

Brehm, J. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance . New York, NY: Academic Press;

Brewer, M. B. (2003). Optimal distinctiveness, social identity, and the self. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 480–491). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Bushman, B. J., & Stack, A. D. (1996). Forbidden fruit versus tainted fruit: Effects of warning labels on attraction to television violence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 2 , 207–226.

Eagly, A. H. (1978). Sex differences in influenceability. Psychological Bulletin, 85 , 86–116;

Eagly, A. H. (1983). Gender and social influence: A social psychological analysis. American Psychologist, 38 , 971–981.

Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. (2007). Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders . Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press;

Eagly, A. H., & Chravala, C. (1986). Sex differences in conformity: Status and gender-role interpretations. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 10 , 203–220.

Eagly, A. H., & Johnson, B. T. (1990). Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108 , 233–256;

Eagly, A. H., Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C., & van Engen, M. L. (2003). Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing men and women. Psychological Bulletin, 129 , 569–591.

Eagly, A. H., Karau, S. J., & Makhijani, M. G. (1995). Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 117 , 125–145.

Eagly, A. H., Makhijani, M. G., & Klonsky, B. G. (1992). Gender and evaluation of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111 , 3–22;

Geis, F. L., Boston, M. B., and Hoffman, N. (1985). Sex of authority role models and achievement by men and women: Leadership performance and recognition, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49 , 636–653;

Griskevicius, V., Goldstein, N. J., Mortensen, C. R., Cialdini, R. B., & Kenrick, D. T. (2006). Going along versus going alone: When fundamental motives facilitate strategic (non)conformity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91 , 281–294.

Heilman, M. E., Block, C. J., & Martell, R. (1995). Sex stereotypes: Do they influence perceptions of managers? Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 10 , 237–252.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (1997). Strength of identification and intergroup differentiation: The influence of group norms. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27 , 603–609;

Kim, H., & Markus, H. R. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity? A cultural analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77 , 785–800.

Kray, L. J., Reb, J., Galinsky, A. D., & Thompson, L. (2004). Stereotype reactance at the bargaining table: The effect of stereotype activation and power on claiming and creating value. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30 , 399–411.

Megargee, E. I. (1969). Influence of sex roles on the manifestation of leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 53 , 377–382;

Miron, A. M., & Brehm, J. W. (2006). Reaktanz theorie—40 Jahre spärer. Zeitschrift fur Sozialpsychologie, 37 , 9–18. doi: 10.1024/0044-3514.37.1.9.

Nyquist, L. V., & Spence, J. T. (1986). Effects of dispositional dominance and sex role expectations on leadership behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50 , 87–93.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Sanders, D. Y. (1976). American graffiti: Effects of authority and reactance arousal. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2 , 264–267.

Porter, N., Geis, F. L., Cooper, E., & Newman, E. (1985). Androgyny and leadership in mixed-sex groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49 , 808–823.

Rojahn, K., & Willemsen, T. M. (1994). The evaluation of effectiveness and likability of gender-role congruent and gender-role incongruent leaders. Sex Roles, 30 , 109–119;

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (1999). Feminized management and backlash toward agentic women: The hidden costs to women of a kinder, gentler image of middle-managers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77 , 1004–1010.

Shackelford, S., Wood, W., & Worchel, S. (1996). Behavioral styles and the influence of women in mixed-sex groups. Social Psychology Quarterly, 59 , 284–293.

Shoham, V., Trost, S. E., & Rohrbaugh, M. J. (Eds.). (2004). From state to trait and back again: Reactance theory goes clinical . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Snyder, C. R., & Fromkin, H. L. (1977). Abnormality as a positive characteristic: The development and validation of a scale measuring need for uniqueness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86 (5), 518–527.

Terry, D., & Hogg, M. (1996). Group norms and the attitude-behavior relationship: A role for group identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22 , 776–793.

Visser, P. S., & Krosnick, J. A. (1998). The development of attitude strength over the life cycle: Surge and decline. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75 , 1389–1410.

Wolf, S., & Montgomery, D. A. (1977). Effects of inadmissible evidence and level of judicial admonishment to disregard on the judgments of mock jurors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 7 , 205–219.

Wood, W. (1987). A meta-analytic review of sex differences in group performance. Psychological Bulletin, 102 , 53–71.

World Economic Forum. (2013). The global gender gap report 2013 . Retrieved from http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2013/

The strong emotional response that we experience when we feel that our freedom of choice is being taken away when we expect that we should have choice.

Principles of Social Psychology - 1st International H5P Edition Copyright © 2022 by Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani and Dr. Hammond Tarry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

DOING GENDER FOR DIFFERENT REASONS: WHY GENDER CONFORMITY POSITIVELY AND NEGATIVELY PREDICTS SELF-ESTEEM

2000, Psychology of Women Quarterly

Related Papers

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

C. Moss-racusin , Jessica Good , D. Sanchez

Journal of Sex Research

Diana Sanchez

Diana Sánchez

Psychology of Women Quarterly

diana sanchez

The present study examined the relationship between investment in gender ideals and well-being and the role of external contingencies of self-worth in a longitudinal survey of 677 college freshmen. We propose a model of how investment in gender ideals affects external contingencies and the consequences for self-esteem, depression, and symptoms of disordered eating. Specifically, we find that the negative relationship between investment in gender ideals and well-being is mediated through externally contingent self-worth. The model showed a good fit for the overall sample. Comparative model testing revealed a good fit for men and women as well as White Americans, Asian Americans, and African Americans.

Journal of Business Ethics

Lucas Monzani

Role congruity theory affirms that female managers face more difficulties at work because of the incongruity between the female gender role and the leadership role. Furthermore, due to this incongruity it is harder for female managers to perceive themselves as authentic leaders. However, followers’ attributions of prototypicality could attenuate this role incongruity and have implications on a leader’s organizational identification. Hence, we expect male leaders to be more authentic and to identify more with their organization, in particular compared to female leaders low in prototypicality. We hypothesized that (1) authentic leadership mediates the relation between leaders’ gender and their organizational identification, but that this indirect effect (2) is conditional of team prototypicality. To test these hypotheses, we conducted an online experiment with 149 managers (Mage = 43.42 years SD = 11.41; 43% female) from different work sectors using a 2 (gender participant) x 2 (prototypicality: low vs. high) between-subject design. As predicted, men scored higher on authentic leadership, and three dimensions of authentic leadership partially mediated the effect of gender on organizational identification. In the low prototypicality condition, women scored lower in authentic leadership and identified less with the organization, whereas in the high prototypicality condition no gender differences were found.

Journal of Research in Personality

Alicia Del Prado

Lennart Hallsten

Psychology of Men & Masculinity

Although heterosexual men typically hold positions of dominance in society, negative aspects of masculinity could lead some men to feel that their gender group is not valued by others (D. A. Prentice & E. Carranza, 2002). Previous research has largely overlooked the impact of men’s own perceptions of their gender group membership on their relationship outcomes. To address this gap, we posited that when heterosexual men feel that their gender identity is devalued, they may relate better to close others who have devalued identities (e.g., their female romantic partners). Specifically, we predicted that heterosexual men who view their masculine gender identity as important but devalued would more successfully take the perspective of their female partner. Results confirmed predictions, such that for undergraduate men whose gender identity was important, lower levels of perceived group value predicted greater ability to take perspective with their romantic partners. Implications for men’...

Annual review of psychology

Mahzarin R. Banaji

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

John Jost , Rachel Calogero

RELATED PAPERS

Nicholas A Palomares

Personal Relationships

Lora Park , Ariana Young

Beth Livingston

Social Psychology

Shaki Asgari

Aoliaocc Chen

Rachel Calogero , Lora Park

Terry Humphreys , Deborah Kennett

Women's Internalization of Sexism: …

Polish Psychological Bulletin

Bogdan Wojciszke

Review of General Psychology

Hart Blanton

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

Handbook of Social Exclusion

Pallavi Chatterjee

Reinventing the Squeal: Young New Zealand women negotiating space in the current sexual culture

Lesley Wright

Amir Rosenmann

Annual Review of Psychology

Galen V Bodenhausen , Sonia Kang

Richard Petty

Kim Chantala

Catherine Sanderson

Psychological Review

Hazel Markus

Mehmood Hassan

Terri Conley

Social Justice Research

Archives of Sexual Behavior

Journal of Applied Social Psychology

Delphine Martinot , S. Guimond

Andrea Vial

Hanna Li Kusterer

Ali Ziegler

Spike W. S. Lee

Motivation and Emotion

Nikos Ntoumanis

Handbook of Motivation and Cognition Across Cultures

Daphna Oyserman

Social and psychological bases of ideology and system justification

Mina Cikara

John T Jost

The Psychology of Social Status

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Gender is a Social Construct Essay

How is gender socially constructed? The essay answers this question. It defines gender as a social construction and explains its significance as a cultural phenomenon.

Introduction

Social construction of gender, relationship between the two genders, sex, gender and gender conformity, works cited.

Gender as a topic has become very popular over the recent past. The global society has witnessed many changes in social construction of gender. According to World Health Organization, gender is a socially constructed trait, conduct, position, and action that a given society considers suitable for men and women. Lockheed (45) defines gender as a given range of characteristics that distinguishes a male from a female.

Gender refers to those attributes that would make an individual be identified as either male or female. As can be seen from the above definitions, gender is more of a social than a physical attribute. We look at gender from a societal point of view. Lepowsky (90) defines social construction as an institutionalized characteristic that is largely acceptable in a given society because of the social system.

Social construction, in a narrower term, refers to the general behavioral patterns of a certain society shaped by beliefs and values. A socially constructed characteristic therefore varies from one organization to another. Different societies have different beliefs and cultural practices that help define them. Therefore, a social construction of one society would be different from another society.

To social constructionists, social construct is a notion or an idea that is considered obvious and natural to a certain group of individuals in a given society, which may be true or not. This means that it holds just to the specific society. In this regard therefore, gender and associated beliefs would vary from one community to another depending on perceptions.

On the other hand, essentialists hold there is a set of characteristics that are universal in a certain entity. This means that a given entity can receive a single definition, regardless of the societal set up. In this regard, gender is a universal entity, irrespective of the society and the cultural beliefs associated with it. This perspective dilutes the notion that gender is a social construction.

This is because it gives it a universal definition, where there is a remarkable difference in the social construct of different societies in the world. This is due to differences in religion, cultural beliefs and civilization. To validate this discussion, the essay is based on social constructionist thinking as opposed to essentialism.

Gender is socially constructed. As Lepowsky (31) notes, there is a remarkable difference in the way different societies view the two genders that is, male and female. This scholar says that issues related to gender purely take the approach of social constructionists. He says that societies in the world have varied characteristics, depending on cultures.

He notes that the way one society would view the relationship between the two genders would vary from another, which also depend on a number of factors. Lerro (74) is opposed to this notion. He says that gender is best viewed from essentialists’ perspective. He holds that universally, women have always been regarded as the weaker sex, irrespective of the society. In many regions in the world, women have been treated with low esteem.

This is because of the fact that they are physically weak as compared to men. To various societies across the world, women are expected to be below men socially. Although the current wave of change has seen women take active roles in income generating activities, many societies still consider them as home keepers who should always be willing to receive and obey instructions from men.

This scholar’s argument is valid. However, his explanation, though leaning towards essentialism, still points out that gender is a social construct. Although many societies have almost a similar perception regarding gender, the fact is that they have construed the meaning of gender. The perception is a mere creation of the society members.

According to Lepowsky (53), gender cannot take an essentialist approach. The current world has varied perceptions towards women. The society in Saudi Arabia defines gender in a very different way as compared to the United Kingdom society. Saudi Arabia is an Islamic society that follows strict teachings of the holy Quran.

In this society, there is a big social gap between men and women. The society defines a woman as a subordinate who should always serve men. When it comes to addressing issues of importance, a woman must consult a man because by virtue of being a woman, the society assumes that one cannot make a decision personally.

This is a very sharp contrast to how this gender is viewed in a liberal country such as the United Kingdom. This society has completely narrowed the gap between the two genders that what remain are the physiological differences between the two genders. The country has embraced equality between the two sexes, a fact that saw it elect a female Premier Margret Thatcher.

The social environment in Saudi Arabia is very different from that in the United Kingdom. Because of this, the two societies have different views on what the two genders are and how they should relate. While one society is of the view that gender is just but the biological differences that makes one male or female, the other society sees more. It sees difference in roles, freedom, and positions in the society.

The society is waking to a new down where women and men are considered equal. The only differences existing are biological. Man has been the dominant sex over years. Terms such as mankind, chairman and fireman were used to refer to both men and women. However, these are currently considered sexist titles, which should be avoided at all costs. Although the global society is still largely patriarchal, there is an observable effort to create equality between the two sexes.

However, men are not willing to relinquish their prestigious positions in the society. In social centers such as schools and colleges, men would try to prove that they are in control. Plante (6) notes that jokes are always essential in our society. Although they are always taken from the face value as a form of entertainment, it has a purpose beyond entertainment.

This scholar gives an analysis of sexist jokes used by men towards female students in learning institutions. What comes clear is that men still rely much on their physical superiority, as their way of showing dominance. They use force in order to make female students listen to their jokes, which is highly sexist.

When it comes to sex, men completely change. Chappell (19) gives a confession of a certain girl and her sexual encounter. Through this, it can be observed that when a man has the desire for sex, he is willing to bend very low to a woman. However, things change immediately after the process. He becomes rude and he would easily pick mistakes from the same woman.

Gender identity is the biological characteristic that would define an individual’s gender. In this regard, it would be appropriate to just categorize humanity based on sex. This would mean that the two categories would be men and women. However, because of these biological differences between the two sexes, there is another way of classifying the two sexes that is, gender. Gender is more of a social than a biological difference between the two sexes.

As Plante (110) notes, in this approach, the two genders are analyzed based on the abilities and inabilities. Because men are considered stronger physically, they are given a higher rank in the society because it is assumed that their capabilities are superior to those of women. Sex in itself is a gendered word. In many societies, sex is used to emphasize the difference between the two genders.

Because societal pressure, the ‘weaker’ sex (woman) is forced to conform to the position they are given. They conform, not because they like the assigned position, but because they are not allowed to oppose the decision. They may not necessarily accept the position given to them by the society. However, because the society is intolerant and very rigid, they are left with very limited option other than conforming to the norm.

In some instances, women are exposed to physical abuse from their male counterparts who are keen on asserting their authority in the societal set up. Plante (136) says that this high handedness has seen many women suffer in silence, simply because they are women. Gender identity disorder is a syndrome that is always traumatizing.

An individual who cannot clearly be categorized as a man or a woman may find either himself or herself at the center of social stigmatization. Such an individual lacks a gender to identify with in a society that is so keen on identifying individuals based on gender.

It can be seen from the above discussion that gender can be defined differently, depending on the community in question. Depending on the societal structure of a given community, gender will assume a meaning depending on how men and women relate. Unlike sex that is defined based on biological differences, gender is defined based on the behavioral patterns of the two genders and the society’s perception of the concerned individual.

Every society has its own way of viewing men and women and the relationship between the two. In some societies, women are treated with very low esteem. In such societies, gender is held with high esteem, as a way of showing the boundary that exists between men and women. In other societies, civilization has made a woman be accepted as equal to a man hence the term gender has lost its previous meaning.

Issues of gender have raised many questions in the current society. In the current world, women have acquired a new status. They no longer depend on men for everything. As a number of authors note, gender has to be given a new definition other than what it was before. Based on how gender is defined, the current society needs a to re-define it.

Chappell, Marissa. The war on welfare: family, poverty, and politics in modern America . Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010. Print.

Lepowsky, Maria. Fruit of the Motherland: Gender in an Egalitarian Society. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. Print.

Lerro, Bruce. Power in Eden: The Emergence of Gender Hierarchies in the Ancient World . Manchester:Trafford Publishing, 2005. Print.

Lockheed, Marlaine. Gender and social exclusion . Paris: Education Policy series publishers, 2010. Print

Plante, Rebecca. Doing gender diversity: readings in theory and real-world experience . New York: West view Press, 2010. Print.

- Why is society a social construct

- Social Constructs of Childhood

- Social Constructs in Gender: The Social “Cover” of Biological Sex

- Analysis of the Peculiarities of Gender Roles Within Education, Families and Student Communities

- Representation of gender in media

- Everything You’ve Always Wanted to Know About Sex

- Gender Studies and Society

- The Sexual Revolution

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, March 29). Gender is a Social Construct Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-gender/

"Gender is a Social Construct Essay." IvyPanda , 29 Mar. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-gender/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Gender is a Social Construct Essay'. 29 March.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Gender is a Social Construct Essay." March 29, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-gender/.

1. IvyPanda . "Gender is a Social Construct Essay." March 29, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-gender/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Gender is a Social Construct Essay." March 29, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-construction-of-gender/.

Module 9: Gender, Sex, and Sexuality

Gender and socialization, learning outcomes.

- Explain the influence of socialization on gender roles in the United States

- Explain and give examples of sexism

Figure 1. Traditional images of U.S. gender roles reinforce the idea that women should be subordinate to men. (Photo courtesy of Sport Suburban/flickr)

Gender Roles

As we grow, we learn how to behave from those around us. In this socialization process, children are introduced to certain roles that are typically linked to their biological sex. The term gender role refers to society’s concept of how people are expected to look and behave based on societally created norms for masculinity and femininity. In U.S. culture, masculine roles are usually associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles are usually associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination.

Gender role socialization begins at birth and continues throughout the life course. Our society is quick to outfit male infants in blue and girls in pink, even applying these color-coded gender labels while a baby is in the womb. This color differentiation is quite new—prior to the 1940s, boys wore pink and girls wore blue. In the 19th century and early 20th century, boys and girls wore dresses (mostly white) until the age of 6 or 7, which was also time for the first haircut. [1]

Figure 2. Fathers tend to be more involved when their sons engage in gender-appropriate activities such as sports. (Photo courtesy of Shawn Lea/flickr)

Thus, gender, like race is a social construction with very real consequences. The drive to adhere to masculine and feminine gender roles continues later in life. Men tend to outnumber women in professions such as law enforcement, the military, and politics. Women tend to outnumber men in care-related occupations such as childcare, healthcare (even though the term “doctor” still conjures the image of a man), and social work. These occupational roles are examples of typical U.S. male and female behavior, derived from our culture’s traditions. Adherence to them demonstrates fulfillment of social expectations but not necessarily personal preference (Diamond 2002).

The phrase “boys will be boys” is often used to justify behavior such as pushing, shoving, or other forms of aggression from young boys. The phrase implies that such behavior is unchangeable and something that is part of a boy’s nature. Aggressive behavior, when it does not inflict significant harm, is often accepted from boys and men because it is congruent with the cultural script for masculinity. The “script” written by society is in some ways similar to a script written by a playwright. Just as a playwright expects actors to adhere to a prescribed script, society expects women and men to behave according to the expectations of their respective gender roles.

Socialization

Children learn at a young age that there are distinct expectations for boys and girls. Cross-cultural studies reveal that children are aware of gender roles by age two or three. At four or five, most children are firmly entrenched in culturally appropriate gender roles (Kane 1996). Children acquire these roles through socialization, a process in which people learn to behave in a particular way as dictated by societal values, beliefs, and attitudes.

Figure 3. Although our society may have a stereotype that associates motorcycles with men, female bikers demonstrate that a woman’s place extends far beyond the kitchen in the modern United States. (Photo courtesy of Robert Couse-Baker/flickr)

For example, society often views riding a motorcycle as a masculine activity and, therefore, considers it to be part of the male gender role. Attitudes such as this are typically based on stereotypes, which are oversimplified notions about members of a group. Gender stereotyping involves overgeneralizing about the attitudes, traits, or behavior patterns of women or men. For example, women may be thought of as too timid or weak to ride a motorcycle.

Mimicking the actions of significant others is the first step in the development of a separate sense of self (Mead 1934). Recall that according to Mead’s theory of development, children up to the age of 2 are in the preparatory stage, in which they copy actions of those around them, then the play stage (between 2-6) when they play pretend and have a difficult time following established rules, and then the game stage (ages 7 and up), when they can play by a set of rules and understand different roles.

Like adults, children become agents who actively facilitate and apply normative gender expectations to those around them. When children do not conform to the appropriate gender role, they may face negative sanctions such as being criticized or marginalized by their peers. Though many of these sanctions are informal, they can be quite severe. For example, a girl who wishes to take karate class instead of dance lessons may be called a “tomboy,” and face difficulty gaining acceptance from both male and female peer groups (Ready 2001). Boys, especially, are subject to intense ridicule for gender nonconformity (Coltrane and Adams 2004; Kimmel 2000).

One way children learn gender roles is through play. Parents typically supply boys with trucks, toy guns, and superhero paraphernalia, which are active toys that promote motor skills, aggression, and solitary play. Daughters are often given dolls and dress-up apparel that foster nurturing, social proximity, and role play. Studies have shown that children will most likely choose to play with “gender appropriate” toys (or same-gender toys) even when cross-gender toys are available, because parents give children positive feedback (in the form of praise, involvement, and physical closeness) for gender normative behavior (Caldera, Huston, and O’Brien 1998). Charles Cooley’s concept of the looking-glass self applies to gender socialization because it is through this interactive, interpretive process with the social world that individuals develop a sense of gender identity.

Figure 4 . Childhood activities and instruction, like this father-daughter duck-hunting trip, can influence people’s lifelong views on gender roles. (Credit: Tim Miller, USFWS Midwest Region/flickr)

Gender socialization occurs through four major agents of socialization: family, schools, peer groups, and mass media. Each agent reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining normative expectations for gender-specific behavior. Exposure also occurs through secondary agents such as religion and the workplace. Repeated exposure to these agents over time leads men and women into a false sense that they are acting naturally rather than following a socially constructed role.

Family is the first agent of socialization. There is considerable evidence that parents socialize sons and daughters differently. Generally speaking, girls are given more latitude to step outside of their prescribed gender role (Coltrane and Adams 2004; Kimmel 2000; Raffaelli and Ontai 2004). However, differential socialization typically results in greater privileges afforded to sons. For instance, sons are allowed more autonomy and independence at an earlier age than daughters. They may be given fewer restrictions on appropriate clothing, dating habits, or curfew. Sons are also often free from performing domestic duties such as cleaning or cooking and other household tasks that are considered feminine. Daughters are limited by their expectation to be passive and nurturing, generally obedient, and to assume domestic responsibilities.

Even when parents set gender equality as a goal, there may be underlying indications of inequality. For example, boys may be asked to take out the garbage or perform other tasks that require strength or toughness, while girls may be asked to fold laundry or perform duties that require neatness and care. It has been found that fathers are firmer in their expectations for gender conformity than are mothers, and their expectations are stronger for sons than they are for daughters (Kimmel 2000). This is true in many types of activities, including preference for toys, play styles, discipline, chores, and personal achievements. As a result, boys tend to be particularly attuned to their father’s disapproval when engaging in an activity that might be considered feminine, like dancing or singing (Coltraine and Adams 2008). Parental socialization and normative expectations also vary along lines of social class, race, and ethnicity. African American families, for instance, are more likely than Caucasians to model an egalitarian role structure for their children (Staples and Boulin Johnson 2004).

The reinforcement of gender roles and stereotypes continues once a child reaches school age. Until very recently, schools were rather explicit in their efforts to stratify boys and girls. The first step toward stratification was segregation. Girls were encouraged to take home economics or humanities courses and boys to take math and science. Studies suggest that gender socialization still occurs in schools today, perhaps in less obvious forms (Lips 2004). Teachers may not even realize they are acting in ways that reproduce gender differentiated behavior patterns. Yet any time they ask students to arrange their seats or line up according to gender, teachers may be asserting that boys and girls should be treated differently (Thorne 1993).

Schools subtly convey messages to girls indicating that they are less intelligent or less important than boys. For example, in a study of teacher responses to male and female students, data indicated that teachers praised male students far more than female students. Teachers interrupted girls more often and gave boys more opportunities to expand on their ideas (Sadker and Sadker 1994). Further, in social as well as academic situations, teachers have traditionally treated boys and girls in opposite ways, reinforcing a sense of competition rather than collaboration (Thorne 1993). Boys are also permitted a greater degree of freedom to break rules or commit minor acts of deviance, whereas girls are expected to follow rules carefully and adopt an obedient role (Ready 2001).

Mass media serves as another significant agent of gender socialization. In television and movies, women tend to have less significant roles and are often portrayed as wives or mothers. When women are given a lead role, it often falls into one of two extremes: a wholesome, saint-like figure or a malevolent, hypersexual figure (Etaugh and Bridges 2003). Gender inequalities are also pervasive in children’s movies (Smith 2008). Research indicates that in the ten top-grossing G-rated movies released between 1991 and 2013, nine out of ten characters were male (Smith 2008).

Television commercials and other forms of advertising also reinforce inequality and gender-based stereotypes. Women are almost exclusively present in ads promoting cooking, cleaning, or childcare-related products (Davis 1993). Think about the last time you saw a man star in a dishwasher or laundry detergent commercial. In general, women are underrepresented in roles that involve leadership, intelligence, or a balanced psyche. Of particular concern is the depiction of women in ways that are dehumanizing, especially in music videos. Even in mainstream advertising, however, themes intermingling violence and sexuality are quite common (Kilbourne 2000).

Watch the following video to think more about the social construct of gender.

Further Research

Watch this CrashCourse video to learn more about gender stratification .

Gender stereotypes form the basis of sexism. Sexism refers to prejudiced beliefs that value one sex over another. Like racism, sexism has been a part of U.S. culture for centuries. Here is a brief timeline of “firsts” in the United States:

- Before 1809—Women could not execute a will

- Before 1840—Women were not allowed to own or control property

- Before 1920—Women were not permitted to vote

- Before 1963—Employers could legally pay a woman less than a man for the same work

- Before 1973—Women did not have the right to a safe and legal abortion

- Before 1981—No woman had served on the U.S. Supreme Court

- Before 2009—No African American woman had been CEO of a U.S. Fortune 500 corporation

- Before 2016—No Latina had served as a U.S. Senator

- Before 2017—No openly transgender person had been elected in a state legislature

While it is illegal in the United States when practiced as overt discrimination, unequal treatment of women continues to pervade social life. It should be noted that discrimination based on sex occurs at both the micro- and macro-levels. Many sociologists focus on discrimination that is built into the social structure; this type of discrimination is known as institutional discrimination (Pincus 2008).

Figure 4. In some cultures, women do all of the household chores with no help from men, as doing housework is a sign of weakness, considered by society as a feminine trait. (Photo courtesy of Evil Erin/flickr)

Like racism, sexism has very real consequences. Stereotypes about females, such as being “too soft” to make financial decisions about things like wills or property, have morphed into a lack of female leadership in Fortune 500 Companies (only 24 were headed up by women in 2018!). We also see gender discrepancies in politics and in legal matters, as the laws regarding women’s reproductive health are made by a largely male legislative body at both the state and federal levels.

The Pay Gap

One of the most tangible effects of sexism is the gender wage gap. Despite making up nearly half (49.8 percent) of payroll employment, men vastly outnumber women in authoritative, powerful, and, therefore, high-earning jobs (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Even when a woman’s employment status is equal to a man’s, she will generally make only 81 cents for every dollar made by her male counterpart (Payscale 2020). Women in the paid labor force also still do the majority of the unpaid work at home. On an average day, 84 percent of women (compared to 67 percent of men) spend time doing household management activities (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). This double-duty keeps working women in a subordinate role in the family structure (Hochschild and Machung 1989).

Figure 5 . In 2017 men’s overall median earnings were $52,146 and women’s were $41,977. This means that women earned 80.1% of what men earned in the United States. (Credit: Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor)

The Glass Ceiling

The idea that women are unable to reach the executive suite is known as the glass ceiling. It is an invisible barrier that women encounter when trying to win jobs in the highest level of business. At the beginning of 2021, for example, a record 41 of the world’s largest 500 companies were run by women. While a vast improvement over the number twenty years earlier – where only two of the companies were run by women – these 41 chief executives still only represent eight percent of those large companies (Newcomb 2020).

Why do women have a more difficult time reaching the top of a company? One idea is that there is still a stereotype in the United States that women aren’t aggressive enough to handle the boardroom or that they tend to seek jobs and work with other women (Reiners 2019). Other issues stem from the gender biases based on gender roles and motherhood discussed above.

Another idea is that women lack mentors, executives who take an interest and get them into the right meetings and introduce them to the right people to succeed (Murrell & Blake-Beard 2017).

Women in Politics

One of the most important places for women to help other women is in politics. Historically in the United States, like many other institutions, political representation has been mostly made up of White men. By not having women in government, their issues are being decided by people who don’t share their perspective. The number of women elected to serve in Congress has increased over the years, but does not yet accurately reflect the general population. For example, in 2018, the population of the United States was 49 percent male and 51 percent female, but the population of Congress was 78.8 percent male and 21.2 percent female (Manning 2018). Over the years, the number of women in the federal government has increased, but until it accurately reflects the population, there will be inequalities in our laws.

Figure 6 . Breakdown of Congressional Membership by Gender. 2021 saw a record number of women in Congress, with 120 women serving in the House and 24 serving in the Senate. Gender representation has been steadily increasing over time, but is not close to being equal. (Credit: Based on data from Center for American Women in Politics, Rutgers University)

Global Sexism

Gender stratification through the division of labor is not exclusive to the United States. According to George Murdock’s classic work, Outline of World Cultures (1954), all societies classify work by gender. When a pattern appears in all societies, it is called a cultural universal. While the phenomenon of assigning work by gender is universal, its specifics are not. The same task is not assigned to either men or women worldwide. But the way each task’s associated gender is valued is notable. In Murdock’s examination of the division of labor among 324 societies around the world, he found that in nearly all cases the jobs assigned to men were given greater prestige (Murdock and White 1968). Even if the job types were very similar and the differences slight, men’s work was still considered more vital.

In parts of the world where women are strongly undervalued, young girls may not be given the same access to nutrition, healthcare, and education as boys. Further, they will grow up believing they deserve to be treated differently from boys (UNICEF 2011; Thorne 1993).

Think It Over

- In what way do parents treat sons and daughters differently? How do sons and daughters typically respond to this treatment?

- How is children’s play influenced by gender roles? Think back to your childhood. How “gendered” were the toys and activities available to you? Do you remember gender expectations being conveyed through the approval or disapproval of your playtime choice?

- What can be done to lessen the sexism in the workplace? How does it harm society?

- Maglaty, J. 2011. "When did girls first start wearing pink?" The Smithsonian. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/when-did-girls-start-wearing-pink-1370097/ . ↵

- Revision, Modification, and Original Content. Authored by : Sarah Hoiland and Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Gender. Authored by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:IThELyrX@5/Gender . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected].

- Gender Equality: Now. Provided by : WorldFish. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4viXOGvvu0Y . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Gender Roles. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/12-1-sex-gender-identity-and-expression . Project : Sociology 3e. License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Is Gender Real? -8-bit Philosophy. Provided by : Wisecrack. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gkilQ87UUj8&index=50&list=PL93FF46F5BC6A27CF . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Self Assessment — A Study of the Relation of Gender and Self-esteem in Conformity

A Study of The Relation of Gender and Self-esteem in Conformity

- Categories: Self Assessment

About this sample

Words: 2267 |

12 min read

Published: Oct 22, 2018

Words: 2267 | Pages: 5 | 12 min read

Table of contents

Gender and self-esteem differences in conformity: revisiting asch’s conformity test.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1435 words

6 pages / 2514 words

1 pages / 507 words

4 pages / 1619 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Self Assessment

Cultural competence is an essential aspect of providing quality healthcare, particularly in diverse and multicultural societies. It involves understanding and respecting the beliefs, practices, and needs of individuals from [...]

Adams, P., & Maclaine, S. (1999). Gesundheit!: Bringing Good Health to You, the Medical System, and Society through Physician Service, Complementary Therapies, Humor, and Joy. Inner Traditions.Allen, J. (2015). You Can Change: [...]

Self-evaluation is a reflective process that holds the key to personal and professional growth. This essay explores the significance of self-evaluation as a tool for enhancing one's capabilities and achieving goals. Drawing from [...]

After assessing my diet through the process of recording my intake of food over the course of two days and analyzing its nutritional value, relative to my gender, weight, height, activity level and age, I have successfully [...]

The HEXACO Personality Inventory is a six-dimensional model of human personality that is constructed by Ashton (2013). A lot of researchers did make use of the Big Five framework since 1990, but now many researchers make use of [...]

I took all five surveys that were distributed to us in class. Surprisingly, the results of each survey were parallel with each other. For the 16 Personalities test, I was assigned the Defender personality type. This personality [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Gender Identity and Expression in the Early Childhood Classroom: Influences on Development Within Sociocultural Contexts (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Barbara Henderson, Voices coeditor

Gender is an element of identity that young children are working hard to understand. It is also a topic that early childhood teachers are not always sure how best to address.

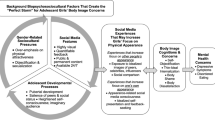

It’s not surprising, then, that Jamie Solomon’s article is the third teacher research study Voices of Practitioners has published that focuses directly on gender, joining articles from Daitsman (2011) and Ortiz, Ferrell, Anderson, Cain, Fluty, Sturzenbecker, & Matlock (2014). Jamie Solomon’s teacher research demonstrates how pedagogy that takes a critical stance on gender stereotyping is a social justice issue because the performance of femininity still maps directly onto disparities in opportunity within our society.

Further, she suggests how the male/female gender binary remains a default perspective and suggests how a more inclusive view of the gender spectrum can enhance and inform our practice and worldview. Her work interprets instances that arose naturally in her teaching, and it displays how teacher research is simultaneously a study of our professional and our personal selves.

During the past 10 years of teaching in the early childhood field, I have observed young children as they develop ideas about gender identity. I soon came to understand gender expression as a larger social justice issue, realizing how external influences were already at work inside the preschool classroom, impacting children's interactions and choices for play and exploration.

This matter became a great priority in my professional life, leading me to look for ways to advocate for change. Some of this eagerness stemmed from my own frustrations about gender inequity and how, as a woman, I have felt limited, misunderstood, and pressured by societal constructs. These personal experiences inspired me to help further discussions about gender development within the early childhood field so that, one day, young children might grow up feeling less encumbered by unfair social expectations and rules.

Teaching preschooI for six years at a progressive school, I was able to engage in ongoing learning opportunities, including observation and reflection. The school's emergent curriculum approach required me to pay close attention to the children's play in order to build the curriculum and create environments based on their evolving interests.

Early one semester, while on a nature field trip, I noticed great enthusiasm coming from a small group that consisted mostly of girls. They attempted to "make a campfire" using sticks and logs. After observing several other similar play scenarios and listening to their discussions, I began building a curriculum based on the children's evolving interests. I started by offering opportunities to encourage this inquiry—for example, through drawing activities and providing tools to more closely explore the properties of wood. Several weeks later, I was gratified to see that among those most deeply engaged in our emerging curricular focus on wood, fire, and camping, the majority continued to be girls. The girls' behavior and interests involved characteristics historically categorized as masculine: joyfully getting dirty, doing hard physical work (in this case with hand tools), and being motivated by a perceived sense of danger acted out in their play—for example, pretending that a fire might erupt at any moment.

These exciting observations prompted me to investigate how a particular curriculum might encourage and support children to behave outside of society's gender constructs. My understanding of gender influences built over time; each year I noticed the power and presence of these influences in the classroom.

These questions guided my study:

- How can I offer a curriculum that provides children with more opportunities for acting outside of traditional gender roles?

- How can I encourage and support children who wish to behave outside of traditional gender roles?

- How can I foster increasingly flexible thinking about gender among 4- and 5-year-old children?

The following study highlights excerpts not only from our major emergent project on camping and firemaking, but also from examples drawn from all of my teaching experiences that spring semester.

Literature review

Young children are continually making sense of their world, assimilating novel information and modifying their theories along the way. Most influences in the lives of young children—both human and environmental—reinforce existing stereotypes (Ramsey 2004).

Without prominent caring adults helping them consider perspectives that challenge the status quo, children, left to their own devices, tend to develop notions that conform with stereotypes (Ramsey 2004). If children are regularly exposed to images, actions, people, and words that counter stereotypes—for example through books, photographs, stories, and role models—they are likely to modify and expand on their narrow theories (Brill & Pepper 2008).

Thus, educators of young children should offer their student different perspectives, including those that counter society's confined constructs, to allow children access to a range of roles, expressions, and identities (Valente 2011). Without such efforts, we stymie young children's development, keeping them from realizing the extent of their potential.

During this teacher research project, I found many examples of girls crossing traditional gender role boundaries but only a few examples involving boys. Some researchers believe this phenomenon, a common finding in gender studies, results from our male-dominated culture, in which being male or having male characteristics is associated with power, opportunity, and prestige (Daitsman 2011).